Fads and Fallacies: Art is Life

6 Minute Read

This article is one of a series of articles from Metalsmith Magazine "Fads and Fallacies". For this 1987 Spring issue, A. Stiletto how Art is Life.

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

In "The Colony of Money" the figure of Fast Eddie Felson is resurrected thrice-fold: in Richard Price's script as a metaphor of the inveterate hustler in every man, in Martin Scorsese's recurring directional homily of moral redemption and in Paul Newman's uncanny facility with the role he created 25 years earlier. Newman's performance, in particular, attests to the actor's prowess in revivifying the faded relevance of the "The Hustler." Thought now a cinematic metaphor, Fast Eddie has matured through Newman's re-presentation. We are no longer certain of his character as a dated stereotype, but are forced to appraise its continuing verisimilitude. As Felson has grown older and wiser in his portrayal, so has Newman's concept of a hustler.

To paraphrase William Gass, who has often ruminated on the figures of life: Art is life, in terms of a film, a painting, in terms of a bracelet, in terms of a teapot; it is incurably figurative, and the world the artist makes is always a metaphorical model of our own.

Throughout much of the 20th century, artists have eschewed representation, bypassing such artifice in the search for immediate expression, for primal substance. Recently, however, figurative powers seem to have returned, an emergence of stylized "new heroes," in the work of paint-box stars like David Salle or Keith Haring. Maybe another cycle has run its course, fads on the wane and fads on the rise.

It is more likely, as history will attest, that the peripatetic figure was just languishing about the house, waiting for fashions to change, for the right ensemble, so it could hit the club circuit again. Like Fast Eddie, these "new heroes" are a little wiser, a little more dapper, but we know a hustler when we see one.

Out on Seventh Avenue, where fashion mimics art, and vice versa, and where belief in figurative powers remains steadfast, "new heroes" are a seasonal occurrence. Take for example, Azzedine Alaia, this "new original" with his skintight, sexy, black leather suits has brought to the force once again the ineluctable assets of the female body. He has prefigured rather than transfigured the essence of physicality. In the argot of the fashion world, Alaia has created the "woman of the 80's." With grace and serenity, he has articulated a fresh view of luxury based on a modern seduction. Caught up in the euphoria of these revelations, I had to be reminded that for women the seduction principle has long been an obstacle to professional advancement and social freedom.

In fashion, the notion of the figure carries a dual meaning. On one hand, the figure denotes the silhouette, a corporeal shadow, a graphic outline of the organic formations of muscle, bone and fat that defines the species. On the other, the figure connotes a type, a representation of the designer's ideals and values. In a metaphorical sense, it carries the interpretation of "the woman of the 80s" or "the hustler," for that matter, in the persona of mask of the designer's creations. Clothes make the man in their image. The strategy of fashion is not only to physically enhance the body but also to provide the contemporary relevance of the wearer's psychological, ideological and sociological costume. For designer and wearer alike, the figure, in this second sense, is an abstraction controlled by the designer's medium and the wearer's choice.

Fashion must constantly assert the supremacy of the designer's image over the innate attraction of the wearer for his own body. The dialectic for his own body. The dialectic is between eroticism and exorcism, between the object of fashion—the wearer struggling with private hedonistic urges—and the subject of fashion—the designer seeking commercial stereotypes. Fashion ministers to exorcism even in the most unlikely of venues. The most sensational instance that comes to mind is the ultimate erotic ritual of sexist manipulation, the striptease. As Roland Barthes has opined, "There is an underlying significance of the G-string covered with diamonds and sequins which is the very end of striptease. The ultimate triangle, by its pure and geometrical shape, by its hard and shiny material, bars the way to the sexual parts like a sword of purity, and definitely drives the woman back into a mineral word, the precious stone being the irrefutable symbol of the absolute object, that which serves no purpose."

Back on the Avenue, this struggle between wearer and designer, control versus freedom of image manipulation, stuck in my mind as I attended FIT's recent day-long symposium on 20th-century jewelry [see review in this issue]. After the morning's palatable agenda of historians charting a noteworthy, though at times gentrified, course through European jewelry, we were offered a showcase of contemporary practitioners that included Paloma Picasso and Robert Lee Morris. Now, the disparity in their work was evident in their slides, but the similarity in their approach only began to reveal itself as we escaped the grasp of their enticing presentations. Both sought to transfix an appropriate model for jewelry design based on their idea of fashionable wearer.

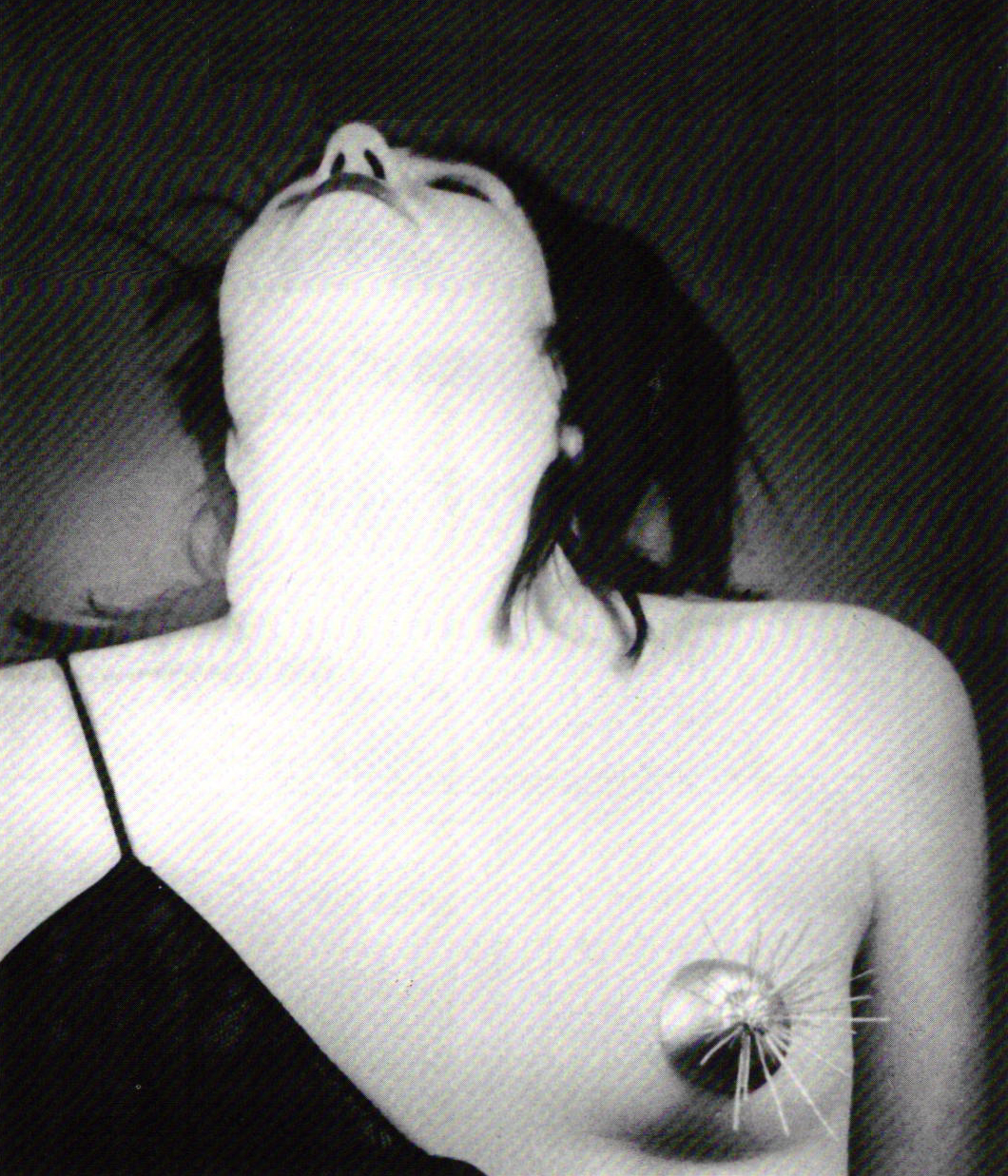

In thinking about Paloma Picasso's work, I can't help but recall Helmut Newton's now famous photo of her, barebreasted, modeling Karl Lagerfeld's scandalous half-dress and her own gold bangles. The jewelry and even the dress appears insignificant as she assumes the posture of "naked" adornment. Picasso's sensuality, a beguiling attribute that resonates with the mere mention of her name, translates into bull's-eye lust, the female body endowed for gratification. Like Alaia, she tries to define the woman of the 80's by bringing to the fore the assets of the female body. Like Alaia, her jewelry evinces a discrete serenity that denies the intimacy of the flesh using the body instead to parade a cold clinical object of desire. Her stones, one more brilliant and colorful than the next, nakedly glisten in their gold bezels, dangle from gold chains and languish atop gold ring shanks. To paraphrase Barthes, she drives the woman back into the materialist world, the precious stone being the target of gratuitous seduction.

Robert Lee Morris, like Picasso, has attained celebrity status in his attempts to mod the woman of the 80's. He is proud of his success in constructing a context of influence and control through overwhelming store display and the covers of the fashion press. He claims that when customers walk into his store, Artwear, he wants them to feel the excitement of an archaeological dig. His now famous truncated torsos, Graecian plaster casts that at times look like breastplates of Roman centurions, blend well with his brutalist displays of antiquity in ruins. His jewelry that borrows from neoprimitive and neoclassical styles is self-consciously distanced from contemporary usage. He creates an ambiance not of a salon but a tomb, where the idiosyncratic ego is embalmed in the artifact. He has ingeniously created an ersatz notion of history where the body is revered for its chaste state of the flesh and where jewelry is the armor of status.

Both Picasso and Morris have repossessed the value of jewelry from the domain of the wearer's bodily interpretation. They have become the ultimate connoisseurs in the fictional world of rarefied commodities - for Picasso commodities of sexuality and for Morris those of status. In effect they have made strides toward securing for the jewelry designer the incongruous clothing of the object in disguise. They are the new heroes of fashion jewelry, a little more proficient and polished, but hustlers nonetheless.

A. Stiletto works in and around New York and writes a regular column on fashion.

You assume all responsibility and risk for the use of the safety resources available on or through this web page. The International Gem Society LLC does not assume any liability for the materials, information and opinions provided on, or available through, this web page. No advice or information provided by this website shall create any warranty. Reliance on such advice, information or the content of this web page is solely at your own risk, including without limitation any safety guidelines, resources or precautions, or any other information related to safety that may be available on or through this web page. The International Gem Society LLC disclaims any liability for injury, death or damages resulting from the use thereof.

The All-In-One Jewelry Making Solution At Your Fingertips

When you join the Ganoksin community, you get the tools you need to take your work to the next level.

Trusted Jewelry Making Information & Techniques

Sign up to receive the latest articles, techniques, and inspirations with our free newsletter.