The Work of Lilly Fitzgerald

The jewelry of Lilly Fitzgerald is washed in serenity. There is a soothing balance, peacefulness, and grace to her timeless one-of-a-kind creations. Fitzgerald strives to select materials that demonstrate extraordinary character: all have spirit, an innate quality of life that, in her opinion, requires only an attractive frame to complete the composition. However, before this union can occur Fitzgerald, a self-taught metalsmith, must occasionally struggle with technical design problems that do not come as easily as does her ability to discover aesthetically pleasing materials. Nonetheless, she pushes her talents and resources, yielding creations worthy of a master goldsmith.

8 Minute Read

The jewelry of Lilly Fitzgerald is washed in serenity. There is a soothing balance, peacefulness, and grace to her timeless one-of-a-kind creations. Fitzgerald strives to select materials that demonstrate extraordinary character: all have spirit, an innate quality of life that, in her opinion, requires only an attractive frame to complete the composition.

However, before this union can occur Fitzgerald, a self-taught metalsmith, must occasionally struggle with technical design problems that do not come as easily as does her ability to discover aesthetically pleasing materials. Nonetheless, she pushes her talents and resources, yielding creations worthy of a master goldsmith.

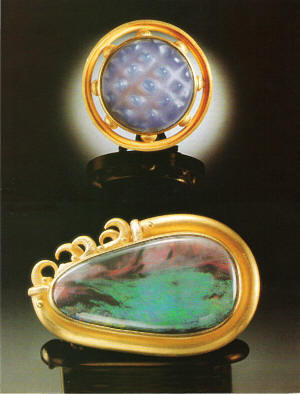

| Brooch, 2001 Black Opal, 22K yellow gold 2 x 1 " Photo: Larry Stein | |

| Brooch, 2000 Carved chalcedony, pearls, 22K yellow gold 1 1/2″ diam. Photo: Larry Stein |

It is the difficulty of discovering inspirational materials that challenges Fitzgerald most. "It's hard to find materials with substance and soul-the right stone, piece of glass, interesting object, or funk little thing," she laments. It is those precious quarries, seeds for a glorious fusion of nature's morsels and gold, which launch her in a different artistic direction. This spontaneity, this searching for the true essence of the thing, is the whole basis of her work ethic.

For instance, a beautiful piece of branch coral with natural markings resembling primitive dancing figures "just needed a pretty frame around it," Fitzgerald advises. The combination of colors and textures reveals her talent for sensual expression. A recessed frame of polished and textured 22-karat gold surrounds the porous, open-grain branch coral-a pristine specimen revealed sensitively through noninvasive, understated boundaries.

| Brooch, 2000 branch coral, 22k yellow gold 1 7/8 x 1 3/4″ Photo: Larry Stein |

The same can he said for a remarkable aquamarine brooch: a marquis carved into the surface by Tom Muensteiner is mirrored by delicate hammer-set marquis diamonds branching off from the stone's bezel. Round-cut diamonds and spherical mounds of gold merging between the bezel and outer frame create graceful echoes of the stone's shape without overpowering it. Yet another brooch, featuring an oval cabochon of quartz, receives an even higher level of enhancement. While a thin gold bezel encircles the stone, a plenitude of tiny soldered gold spheres crown and cascade down the front.

Although Fitzgerald does not do her own lapidary work, she did choose to sandblast the reverse of this quartz, which affords it the opaque, buttery hue. Sometimes, the centerpiece element is so exquisite that she envisions a gold frame that barely disturbs the stone's shape and appearance serving as a mere extension of the piece" Such is the case with a vertically deployed Montana moss agate, whose countenance evokes a single, charred pine tree looming, ghostlike and skeletal, from a smoky, emblazoned sky. The closely adhered bezel and matte texture of the gold base are sublime in their minimalism.

| Brooch, 1996 quartz, 22k yellow gold 2 1/8 x 1 1/4″ Photo: Jonathan Kannair |

Fortunately, Fitzgerald's jewelry speaks for itself, as she does not like to talk about her work.

Nevertheless, what she does say is quite poignant: "It's not a question of trying to be different, but finding materials with a spirit that speak to me. There are so many jewelers and so much stuff. At shows, I see a lot of derivative work: there is a very incestuous kind of inspiration that goes around when people don't get out and see things."

Fitzgerald's philosophy or, jewelry making is simple: "I love design and drawing, finding, and getting the materials; then 1 enter the dark tunnel of the fabrication process, and come out the other end."

Fitzgerald's inspiration derives from subliminal impressions made by images or experiences from her daily life- a doorknob, a particular stone, and various natural ephemera. She expresses particular excitement over a series of pendants and brooches incorporating butterfly and moth wings in which an extreme contrast occurs between the fragile wings and hard metal. First, she cuts the wings, arranges them, sets a crystal over them, and hopes that they do not shift in their placement when she presses down firmly on the gold frame. Capturing the wings within the porthole-like frame wonderfully isolates their ethereally vibrant, iridescent colors and patterns.

Ironically, Fitzgerald does not deliberately set out to find her muses; they find her, spontaneously rising from images and places mentally stored during her frequent sojourns through Asia, Europe, and the United States, where nostalgic old buildings, museums, ironwork, and architecture serve as visual feasts. Nevertheless, she does not carry a sketchbook or record what she sees. "When something is stored in my memory, it just comes out; it's more like osmosis," she muses. She frequently conjures such recollections in elaborate detail and color back at her Massachusetts home with walking or running. Perhaps it is separation of time and place that allows her to meld impressions into her own creations, for she stresses that her aesthetic does not draw from any one specific cultural source.

| Brooch, 1998 Montana moss agate, 22k yellow gold 2 1/2 x 7/8″ Photo: Larry Stein |

The conceptual sketches she makes in her studio are unplanned. This is where the ideas from her travels resurface on paper. Fitzgerald visualizes exceptionally well in three dimensions. She appreciates detailed drawings and sees them as the floor plan for what happens in the gold. However, she admits that her drawings rarely make it to the bench completely, as the designs change in the metal. Many of her pieces are asymmetrical in design, which she feels lends a certain serenity. "My pieces have more balance than symmetry," she explains. A favorite treatment is the asymmetrical arrangement of accent gemstones or the off- center, angled display of an opal's highly patterned fire.

Fitzgerald's philosophy on jewelry making is simple: "I love design and drawing, finding, and getting the materials; then I enter the dark tunnel of the fabrication process, and come out the other end. My main thrill is the end piece," she states matter-of-factly. On the reverse of a particularly playful piece, for which she selected a stunning blue chalcedony carved by German lapidary Dieter Lorenz, she backed the stone with a detail-incised plate of gold, perforated with holes, and set with pearl feet for balance. The holes have nothing to do with the transference of light through the stone; they are purely decorative. Fitzgerald feels that jewelry is more than just one-sided and enjoys incorporating little surprises and details; and, even though a goldsmith, she prefers looking at and handling jewelry more than wearing it.

She also loves control over the process: "But that's hard to achieve, not being a perfect metalsmith," she admits. Through maturation as an artist, Fitzgerald has become more demanding and has set higher standards for herself, whether in her choice of materials or the technical aspects of her goldworking. In some cases, spontaneous conceptual design grapples with technical reality to achieve the simultaneous appearance of balance and tension. In a most striking brooch, the broken circumference of sandblasted gold mimics the diagonal rust-colored, hairlike inclusions of a quartz. Meanwhile, the bezel-set stone is seemingly suspended in midair, its metallic, glassy reflection captured by the concavity of the frame's interior.

If Fitzgerald cannot solve the technical problems of translating a drawing into gold, she contacts Mark Agerholm, who has done freelance work for her over the past ten years. She values him as a precise technical wizard and an excellent craftsman. Between the two of them, Fitzgerald feels there are few things they cannot accomplish. For instance, while the concept of the rotating clasp of her South Sea pearl necklaces is common, Agerholm designed the internal stop mechanism inside the hollow chamber, adding extra security. Nonetheless, she explains that the need for technical assistance does not often arise. "My designs are pretty simple; I'm not trying to make things that spin around and play music," and true perfection is not something she seeks for her aesthetic.

| BPendant and Chain, 1999 butterfly wing, crystal, seed pearls, silk thread, 22k yellow gold Pendant 1 3/8″ diam.; chain 36″ Photo: Larry Stein |

Originally, Fitzgerald studied liberal arts at the University of Rhode Island and took classes at the Montreal Museum of Fine Art. Returning to Massachusetts , she studied sculpture and painting and took one semester of basic metals, clay, and fiber at the Worcester Art Museum . With an art history background, Fitzgerald learned the majority of her metalworking through trial and error and poring over numerous books and jewelry repair manuals. "I am not a technical person by any- means," she laments. "I would have saved myself a lot of time if I had gone to a bench school to learn the techniques." Nonetheless, the jewelry that she began making as presents for her sisters grew into something larger. When their friends wanted to buy it, she made more. Soon, it began selling and she dropped out of school and started her business in 1976.

During the first couple of years, Fitzgerald worked with copper, as she could afford nothing else; nonetheless, she found contentment, as it is a metal that ages beautifully. Then, she worked in silver for three or four tears, still due to expense. However, Fitzgerald did not like working with silver because she felt it did not combine well with the stones she "was using. Finally, she began working with gold. Now, everything that she hand-fabricates is exclusively 22 karat yellow or rose gold, although hinges and catches are 18 karat. While her one-of -a-kind creations revolve around materials other than just gold, her limited production pieces are predominantly gold-centered and display repeated design elements that arc often cast. Also prominent in Fitzgerald's production line are her signature swan earrings, a graceful combination of lustrous Tahitian pearls and fluid gold.

Still, after twenty-five years, the excitement Fitzgerald feels about her materials and jewelry is more important to her than if it sells, a problem that rarely arises. Amazingly, she admits that there, have only been three pieces-all of them brooches-to which she was particularly attached. She is also committed to finding the right homes for her jewelry and is often brutally frank with people regarding their selection. The same connection she feels with her raw materials only intensifies through her creative process, a process that yields her innate ability to cultivate the spirit of things through the nurturance of gold.

You assume all responsibility and risk for the use of the safety resources available on or through this web page. The International Gem Society LLC does not assume any liability for the materials, information and opinions provided on, or available through, this web page. No advice or information provided by this website shall create any warranty. Reliance on such advice, information or the content of this web page is solely at your own risk, including without limitation any safety guidelines, resources or precautions, or any other information related to safety that may be available on or through this web page. The International Gem Society LLC disclaims any liability for injury, death or damages resulting from the use thereof.

The All-In-One Jewelry Making Solution At Your Fingertips

When you join the Ganoksin community, you get the tools you need to take your work to the next level.

Trusted Jewelry Making Information & Techniques

Sign up to receive the latest articles, techniques, and inspirations with our free newsletter.