The Jewelry of Barbara Seidenath

When Venetian glassmakers sold out their state secrets to Czech glassmakers, Jablonec began its hegemony in glass beads. The region also became renowned for through its production of costume jewelry during the second half of the 18th century, and together the two industries helped it survive numerous European conflicts and two world wars. After World War II, however, the Germans were expelled and resettled in NeuGablonz, the German name for the old Czech town. Jablonec, however, still exists as the center of Czech glass beadmaking.

18 Minute Read

Biography today favors the family over history or culture. Yet people not live outside their times, nor are they immune to accumulated history.

What is now Germany was a loose association of princely states. Bavaria, in the southeastern portion of the region, included the Sudetenland , one of the semi-autonomous regional governments of the 16th and 17th centuries.

As early as 1850 the regions had their own arts and crafts associations, part of a long tradition of support for the arts. Although close to Switzerland, Bavaria is not mountainous, but an area of rolling hills and plains, with forests where wolves, dwarfs, and giants might well have lived. It also includes that section of the current Czech Republic that became part of Germany when Hitler annexed Austria .

Here was a center of art and commerce known as Jablonec, the home of the famed Bohemian glass industry, where, here, even by the end of the 19th century, there was a state technical school for arts and crafts. When Venetian glassmakers sold out their state secrets to Czech glassmakers, Jablonec began its hegemony in glass beads. The region also became renowned for through its production of costume jewelry during the second half of the 18th century, and together the two industries helped it survive numerous European conflicts and two world wars.

After World War II, however, the Germans were expelled and resettled in NeuGablonz, the German name for the old Czech town. Jablonec, however, still exists as the center of Czech glass beadmaking.

It was here that the personal narrative of jeweler Barbara Seidenath met up with European history. Being born 15 years after the end of World War II meant coming to terms with still-fresh memories of German culpability, identity, and I responsibility. But from the turn of the 20th century onward, Germany had also been home to a number of significant art movements. From 1911 to 1914 a loose association of artists who called themselves Der Blaue Reiter (The Blue Rider) exhibited together and published a journal of the same name.

Though disbanded by World War I, the short-lived movement nonetheless exerted a notable influence on German thought; young artists like Seidenath considered them part of their cultural heritage. At the same time, growing up in rural Bavaria gave Seidenath great physical freedom; living in the same village community, as the noted German goldsmith Hermann Junger NN as her other good fortune. In addition to the longstanding support for the applied arts from regional arts councils, it was her long and close association with the Junger family that demonstrated the possibility of a creative life.

| Birdies (ear decoration), 1994 enamel, coral. 18kt gold. 1 x 1/2 x 3/8″ Photo: Roger Birn |

As a young girl Seidenath really did roam the forests of Bavaria , making tree houses and rabbit hutches Even now, her studio is filled with visual reminders of nature, and botanical subjects recur regularly in her jewelry. Her father worked for the forest service and weekends were often spent measuring trees. Seidenath's mother was a school doctor whose schedule and temperament allowed her to oversee handmade projects with her children, much the custom in that time and place.

In considering these early influences, Seidenath recalled that she had even accompanied her grandmother to the village goldsmith for repairs; the young girl was fascinated by the dark workshop and the variety of tools. Her early friendship with Anette Junger, I Hermann's daughter, reinforced her attraction to craft and making, although at the time she was also aware of glass because of its strong regional presence. Teenagers often find other families more convivial than their own, and the Junger household was lively, creative, and intensely appealing. This influence, with the backup of the educational system, contributed to Seidenath's development as a young artist.

Where there is support for art, artists will develop. Where art is made, artists will thrive. With a strong craft tradition behind her, Seidenath enrolled in the three-year state school for glass and jewelry in NeuGablonz. She characterizes it as "pretty rigid, not adventurous …. [Especially] the second year was very, very rigorous. Perfection was expected to within one-tenth of a millimeter! We all hated it, but I learned a lot."

Like many young students, only later did she realize how much she had learned. The level of mastery we have come to associate with European craftsmanship comes not only from the rigorous training and apprenticeship, which one might receive anywhere, but in the greater length of time spent learning one's craft. In Germany the state school gave a solid base in technique at an economic cost that was affordable to most families; graduate school was where one's sense of design and aesthetic. developed.

| Winterstorm (brooch), 1999 enamel, sterling silver 1 3/4 x 1 3/4 x 1/8″ Photo: Marty Doyle | |

| Nest (brooch), 1999 enamel, sterling silver 1 3/3 x 1 3/4 x 1/8″ Photo: Marty Doyle |

After graduating from the State School , Seidenath visited the United States with her family, for the first of what would become many significant American experiences. Back in Munich , she went to work for the established German jeweler Ulrike Bahrs, whose influence may be seen in Seidenath's periodic inclusion of varied and colorful materials. She also worked for Junger, to whose studio she would return several times in the next decade.

Returning to the United States in 1981 she spent a semester at SUNY/New Paltz, where Robert Ebendorf already had a connection with Junger, then lived in New York City , where Robert Lee Morris's downtown gallery Artwear was in its heyday. Here was production jewelry that was not industry-driven. After all, in Jablonec the industry was and is still making conventional designs in wire, castings, and local stones. Seidenath liked the example of a democratic approach to jewelry set by the American jeweler Margaret de Patta. She spent several years in the mid-'80s absorbing New York and the American metals community before returning again to Munich, and to Junger, and eventually entered the Academy of Fine Arts in Munich.

| Thicket (brooch), 2000 enamel, sterling silver, diamonds, niello 1 1/2 x 1 1/2 x 1/8″ Photo: Marty Doyle | |

| Crystalline II (brooch), 2001 enamel, sterling silver 1 1/2 x 1 3/8 x 3/8″ Photo: Marty Doyle |

The Academy gained its superior reputation under the stewardship of Hermann Junger. Here he trained the next generation of German jewelers, led most notably by Otto Kunzli and Daniel Kroger. By the time Seidenath arrived, there was some pressure on this young group to see what they would do after the excitement of in the 1970s, which had been a decade of explosive design innovation everywhere. [1] The list of Seidenath's colleagues reads like a who's who of contemporary German jewelry: Alexandra Bahlmann, Detlef Thomas, Rudolf Bout, Bettina Speckner, Angela Hubel, Christoph Junger, Johan van Aswegen, Karl Fritsch, even American Sondra Sherman , who was living in Germany at the time.

The Munich community was energetic, engaged, and supportive, in an environment where design was already emphasized. Junger came in once a week, but otherwise students were on their own; there was no technical instruction per se, but the prevailing ethos was design-oriented. Later, as before, Seidenath further refined her skills by working for Junger. His method of instruction went something like this: Junger showed her design sketches and asked, How would you make this? It was her job to figure out the fabrication and construct it to his standards. [2]

Evaluating her experience today, Seidenath observes, "It seems very strict and German, and a lot of 17 or 18 year-olds are not accustomed to working to those kind of standards. [But] looking back on it, it has so much value." Seidenath spent 10 years between her undergraduate and graduate degrees. She received her MFA from the Academy of Fine Arts in Munich in 1990, following five more years of study.

After practicing for 20 years, Seidenath fears nothing. She doesn't have to think when soldering; it has become like another language (she is already easily fluent in English as well as German). In 1994 she came to the United States more or less permanently, and joined her husband, metalsmith Louis Mueller, on the faculty of Rhode Island School of Design, where she has taught ever since, in a department itself known for its European orientation and frequent visits from noted German jewelry faculty.

While still in graduate school, Seidenath developed a production line and for several years maintained G&S Designs with colleague Lydia Gastroph. By the time she graduated she had acquired some old equipment and set up a studio, and starting in the early 1990s had begun to participate in exhibitions throughout Europe.

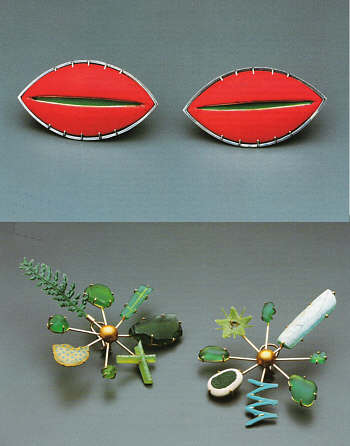

During the 1980s Seidenath'ss work was characterized by color, dimensionality, and vitality. Always Jewelry, it remains, if not exactly conventional, not as frankly original as it would become in another decade. Color choices, though of limited to complementary apple green and scarlet in eye-popping contrast, were highly effective. Enameled surfaces were satiny smooth and the small earring hemispheres (13 mm diameter) eminently wearable.

A fellow student, Justine Wein, got Seidenath thinking about folding the metal and then enameling it. Weir didn't always make finished pieces; many remained as sketches that had been assembled into three dimensions. But Seidenath loved her aesthetic and her irreverent approach to enamel. As anyone who has ever made a paper fan knows, folding is a way of stabilizing a thin, light material. Particularly for enamelists, folding metal foil for strength and avoiding solder (enamel doesn't flow over solder) is an excellent solution to the problem of weight To this day Seidenath's folded enamel jewelry retains a freshness and apparent spontaneity all the more remarkable because of enamel's finicky qualities.

| Wurzelblute (ear decoration), 1991 enamel, coral, 18k gold 2 1/4 x 5/8 x 5/8″ Photo: lochs Grun |

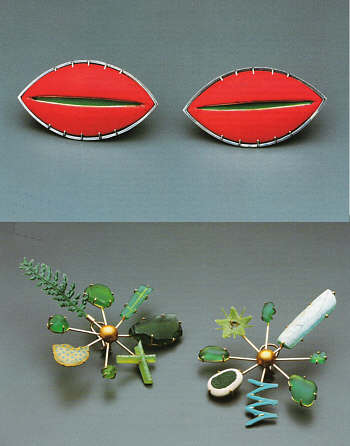

Consistent with her early explorations, Seidenath's thematic choices have remained rooted in nature, including the sexual foundation of all life forms. Cognizant of the symbolism of placing jewelry directly on the body, or in the case of pierced earrings, through the body, Seidenath references some of the methods nature uses to attract attention form, color, movement.

For years she consciously choose "abstracted references to organic forms, ambiguous erotic symbols as well as a palette of bold colors" Seidenath updates the long history of floral jewelry subjects with three-dimensional forms created by traditional metalsmithing techniques. A pair of earrings from 1991 titled Wurzelblute, roughly translated as "flower emerging from root," indeed resembles white daisies emerging from glowing, twisting red roots. There is not so much an attempt to realistically portray the sprouting bloom (being underground, the root would be more likely to be white), as to suggest a burst of floral energy.

In another pair of enameled earrings from 1993, called Rosengartlein, a green field or lawn dotted with carved coral roses, tube-set diamonds, and white pearls is bezeled by a gold picket fence. These are dense little tableaux, with a characteristic limited palette of the same red and green used in the earliest enameled work, but the refined goldsmithing technique and the three-dimensionality of the roses tweaks their sentimental subject matter. Decorative elements are not normally attached to the surface of the enameled form, and Seidenath has continued to embellish the surface through a number of thematic and palette changes, including moving from intense color to black and white, and eventually back to color. She acknowledges multiple aspects of our relationship to nature, from the generative sexuality of the budding shoot, to the mannered garden that shows the controlling intervention of human cultivation.

Seidenath was invited to participate in a show at the Snug Harbor Cultural Center in Staten Island , New York , that opened in 1992. The original theme was to be "virgins" but that was considered to be too controversial, so the exhibition was eventually called "Neoteric Jewelry." Scidenath's contribution concerned the Virgin Mary. She wanted to make reference to the lily, Marv's botanical symbol, and she used the opportunity to continue her exploration of folding, not overlooking an enfolded female archetype. Her pleated earrings, titled The Virgin, are deliciously rude, and although they are lily-white, they are so sexuall suggestive that they do not immediately call to mind the mother of Jesus.

| Beans (car decoration) , 1999 enamel, coral beads, pearls, sterling silver 1/2 x 1 x 1/8″ Photo: Marty Doyle |

The folded work may be considered to be the first evidence of Seidenath's originality. In general, enameled earrings are rare. Since the metal must be enameled on both sides to equalize stress, the repeated layers of enamel needed for good color coverage usually cause earrings to exceed an optimal weight. So not only are Seidenath's earrings a visual delight, to the enamel-literate they have the extra cache of being functional, decorative, and extremely light. She has used a lead-bearing white enamel that can become blue, green, turquoise, and magenta when fired again and again. The repeated firing burns out the enamel on the folds, so that they oxidize to a dark black, accentuating the inverted forms and suggesting individual petals. Although opaque, the same white can be somewhat transparent if applied with a deft touch and not overtired. The pink of the copper shows through and creates a mottled white-green which contrasts nicely with the gold and coral accents.

It is perhaps in this work that the influence of Seidenath's former employer, Ulrike Bahrs, is felt. Since the 1970s Bahrs's work has been characterized by surreal and cerebral compositions and constructions that employ a variety of materials in addition to precious metals, namely glass, stones, and cast objects. Seidenath chooses materials-coral, glass, pearls, and diamonds that have emotional equivalence.

But it is not always easy to spot an artist's direct influences. People who grow up to be artists look at art all the time, and the cultural environment plays a big part. As noted earlier, the legacy of the Blue Rider remained, and Seidenath was most taken with the use of color by such Blue Rider painters as A. Jawlenski and, most notably, Wassily Kandinsky. Seidenath also spent a lot of time learning to understand the work of Joseph Beuys; his drawings and use of materials contributed to the way she looked at the world as an artist. It is perhaps easier to see the impact of Junger, with whom she has had a close relationship, or even Giampaolo Babbetto, the Italian goldsmith, whose simple geometric constructions in gold often bear a single bold color. To Junger's great credit as a teacher and mentor, Seidenath's work has looked only like her own. Like a good director he has enabled her to do her best work, not his.

The most striking example of Seidenath's thematic and color trajectory is a series titled Midnight Sun, a group of brooches and earrings with a winter theme. The title is taken from a song by Johnny Mercer; the visuals came from "seeing beautiful abstracted patterns of winter landscape during a flight to Miami." Seidenath describes her inspiration and intent: "In winter nature and fertility are dormant, the range of colors is muted and reduced, surroundings change. Raindrops turn into a white backdrop like a canvas and conceal familiar things with an obscuring cover." She began with a square format, but conceptually the individual pieces are so much of a piece it doesn't matter which came first. Her intentions are fully realized in these evocative and haunting pieces.

As the work develops over time, the early designs seem tentative when compared to later iterations. Of course they're not really timid, but as the series progresses the mark-making gains in assuredness. By the end the frame has been reduced to the absolute minimum, just enough to hold the enameled element onto the pin back. The powerfully drawn marks supersede technique, and the fact that they are enameled and not drawn gives them depth. One way of describing the work's evolution is to sap that the first generation is like frost on a window, while the later ones resemble a pond where the ice is cracked and water is black beneath the cracks. Like mature artists from Beethoven to Bergman, the work becomes more succinct as it evokes.

Even the earliest brooches and earrings in this series are unlike any other work extant. Partly this is due to the enameling techniques used. Drawings are engraved into the surface before enameling. The surface is then stoned back to flat and layers of transparent enamel are applied, giving back an icy sparkle without using gold. Much information is imparted in these tiny compositions. There is a glimpse of snow with a few scattered diamonds framed by geometric bezels with jagged edges, as if large chunks of ice have broken off. The surfaces are mostly white, the fine silver showing through, broken by a few straight lines. Over time, the lines become more dominant and the underbelly of inhospitable black water is revealed.

Winterstorm and Nest are like charcoal drawings of a maelstrom just barely contained by the most minimal of frames. In the strong frameless black and white drawings, enamel comes closest to its painterly counterpart, again without the distraction of color. All the associations with glass, fragility, even the slang term "ice" for diamonds, spring to mind. The intimate size draws the eye right in, as the fine layers of glass have trapped lines like silt in ice. Occasional use of the frame moves the viewer in and out of the image; contained in a substantial bezel, the brooches and earrings bear heavier black marks, as if the fissures in the ice were growing. A common European construction is to bezel from behind, so that the front contains a solid frame. This has the effect of framing the composition like a painting, and not treating the enameled element as a jewel, as is more commonly done. It's an interesting craft-ly distinction. When the same ideas are executed graphically in silver and niello, the dimensionality possible with enamel is missing.

Although they are all part of the same series, individual pieces have names, such as Thicket, Crowfeet, feet, Winterpond pond, Ice Shard, Thorny. They share evocation of nature and seasonal repose, with only the dim possibility of rebirth in occasional lines of green, yellow, or red, as if the new ° shoots can barely penetrate the carpet of snow. A threatening winter sky hangs over them. They are not a sentimentalized winter wonderland of jingling sleigh bells, but the persistent ice, cold, and black limbs of barren silhouetted shrubs.

It's a reminder of how much can be communicated with line only. Nonetheless, the addition of color, when it does arrive, comes as a welcome intruder. Like a prism the light has broken up into its component colors, with shards thrown off in various directions. All in all, Seidenath's judicious use of color shows remarkable restraint. Too often, enamelists are seduced by brilliant color and sparkly transparency, set off by garish gold cloisonne wires or bezeling. But Seidenath shows her allegiance to form and design be concentrating on a few complementary colors and in the simplicity of black and white. In her early work, she threw a cloak of vivid color on and into her fully dimensional constructions. Then, in the winter series, she has withheld the easy allure of colored glass and dealt with linear suggestion of movement and stasis, in a contained format.

During the early years, Seidenath worked only in opaque enamels, claiming she didn't know bow to use transparents. Since enameling is inherently challenging one doesn't even get the same result from the same color each time it is fired she set herself strong limitations in working with color, for example, just red and green, or later, just black and white; opaque enamel was fired over copper. The winter series, using transparents, however, was fired on fine silver, so that there would be no wrong colors. "Then I started using transparent colors all the time," says Seidenath. "Slowly I added reds, blues. Then I became too comfortable with the format and I didn't want to rely on it or on the same shapes. So I began to break out of the two-dimensional format" Seidenath began to make three-dimensional paper models, scoring and folding the metal structure under the enamel.

After several years of looking into frozen water, reflecting and refracting light, Seidenath is ready to begin to move away from the strictly organic and go with abstraction. Most of the "winter" pieces are brooches because the notion of framing the composition like a camas seemed better suited to the object's placement on clothing, rather than on skin. Seidenath wanted that bit of distance. In the earlier years, when the subject matter was more frankly erotic, it was important for the work to be located directly on the body. As the imagery has become more abstracted it has moved away from the beds. Now the geometrically folded rectangles are even less organic and appear, like shaped camases, to jut out from the wall.

Seidenath's latest work is again small in size and intimate in subject, yet bold and joyful in execution. In addition to the subtle surface of the folded boxlike brooches, there are earrings that are colorful, witty, and feminine. The palette for each pair is still confined to one or two colors, but oh! the surfaces. She takes a conventional format turquoise beads, pearls, gold prongs on an enameled disk and creates a simple and boldly confident arrangement. Rimmed in turquoise or sunny orange beads, the mottled blue enameled surface is not the icy transparency of a winter pond, but a granular translucent frosting of dyed sugar barely fused to the surface. They are as delectable as the w itch's house was to Hansel and Gretel. Putting them on would be like breaking the frozen surface and seeing the sun burst through again.

Marjorie Simon is a metalsmith and writer.

- In addition to the Dutch designers, in Pforzheim the other German center of goldsmithing, Claus Bury and Jens-Rudiger Lorenzen were also breaking boundaries in design and materials.

- Tangentially, metalsmlth Boris Bally has described his Swiss apprenticeship in similar terms. He was given an item to fabricate, with only a detailed sketch and without instruction, and at the end of the day (in reality several days) If it wasn't acceptable, it would be cast into a reject box and he would be asked to start over the next day. The only explanation given was, "It isn't right yet."

- All unattributed quotes taken from communication with the artist.

For background on contemporary German jewelers mentioned, see Munchner Goldschmiede. Schmuck and Geaat, exhibition catalogue, (Munchner Stadtmuseum, 1993), and Peter Dormer and Ralph Turner, the new jewelry: trends+traditions. (London. Thames and Hudson , 1985)

You assume all responsibility and risk for the use of the safety resources available on or through this web page. The International Gem Society LLC does not assume any liability for the materials, information and opinions provided on, or available through, this web page. No advice or information provided by this website shall create any warranty. Reliance on such advice, information or the content of this web page is solely at your own risk, including without limitation any safety guidelines, resources or precautions, or any other information related to safety that may be available on or through this web page. The International Gem Society LLC disclaims any liability for injury, death or damages resulting from the use thereof.

Related Articles

Project Management for Jewelers

Fancy Color Diamonds

Tom Markusen: Holloware Maker with Integrity

Exhibition Concept Evokes Wanderlust

The All-In-One Jewelry Making Solution At Your Fingertips

When you join the Ganoksin community, you get the tools you need to take your work to the next level.

Trusted Jewelry Making Information & Techniques

Sign up to receive the latest articles, techniques, and inspirations with our free newsletter.