Robert Lee Morris: The Business of Marketing Art Jewelry

15 Minute Read

Jewelry was never on his mind—at least not while he was studying art and anthropology in college. It was filmmaking which claimed his most serious career intentions and to which Robert Lee Morris committed himself, until he realized just how many others had made the same choice and how few the industry could really support.

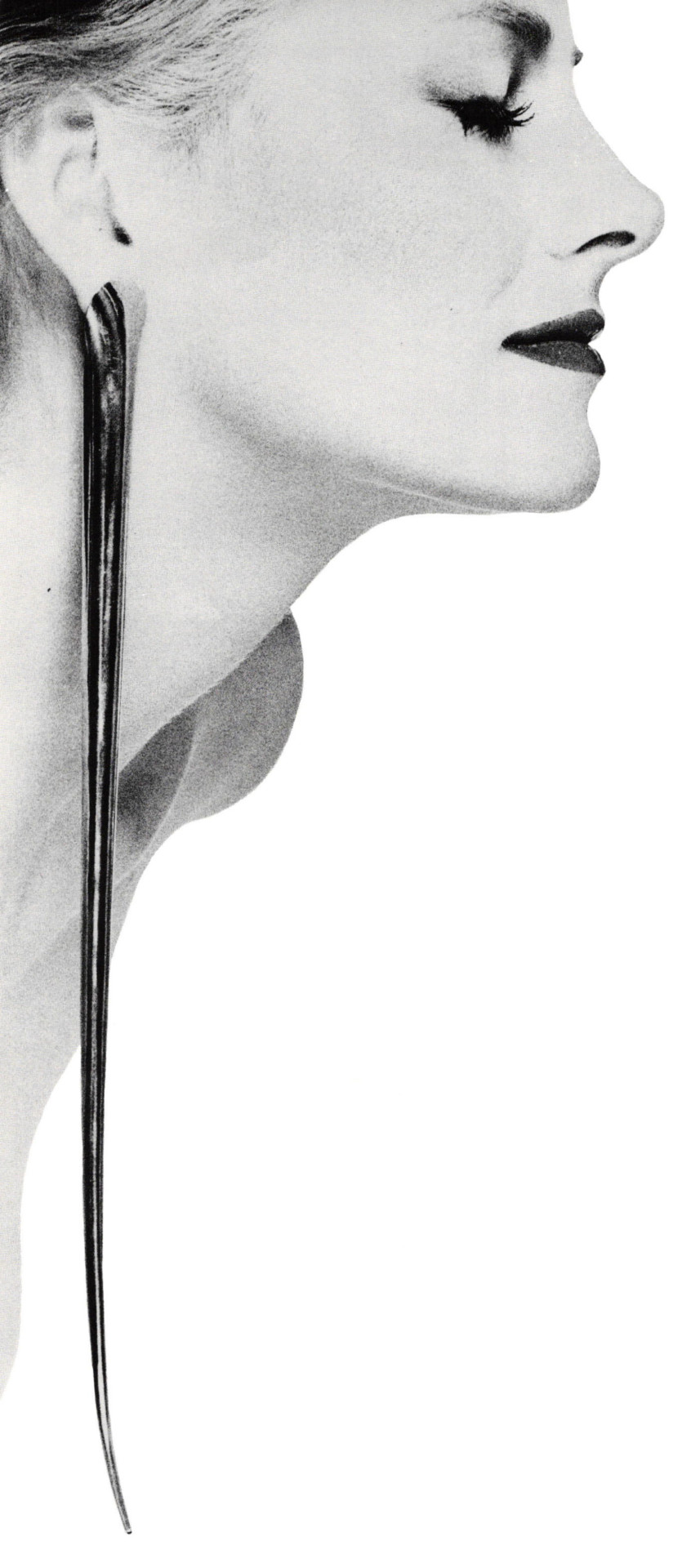

Today at 35, Robert Lee Morris remains a little startled at his own success. A well-known name in the art community as well as in the fashion and jewelry industries, with his bold, sleek and highly imaginative collections Morris has earned countless editorial pages in every major fashion publication both in the United States and abroad. He has received the accolades that come with being asked to accessorize the new lines of such fashion luminaries as Kansai Yamamoto, Anne Klein and Calvin Klein. He has a coveted Coty award to his credit. He is owner and spokesman for Artwear, one of New York's oldest and perhaps best known avant-garde jewelry galleries. Here he has cultivated a jet-set and star-studded clientele, whose members repeatedly visit to replenish their collections of trendsetting jewelry by Morris and his stable of artists. Robert Lee Morris is an internationally acclaimed artist, who has chosen small-scale sculpture for the body as his medium. He has clearly made it—in every sense of the word—in the world of jewelry design. Sitting in his basement office at Artwear, his youthful good looks and personable manner belie the keen business acumen and artistic savvy that have gained him such prominence. But the directness with which he approaches conversation about his achievements more than hints at his intensity.

When his initial career direction in college dissolved, Morris ". . . began to tinker with jewelry, just as a whim, with nothing serious in mind, whatsoever." At the time he was studying sculpture with George Garner at Beloit College in Wisconsin. Morris remembers, "He was a very macho man . . . the epitome of the welder and the man who could lift a crucible of molten steel. He was the man who taught me that jewelrymaking is not necessarily a feminine or weak thing, or a frivolous, decorative thing." In his spare time Garner used to use metal sculpture techniques such as welding to create jewelry. His pieces had a strong influence on Morris. "They were so direct . . . there was no separation between his jewelry and his sculpture. It looked the same. It had the same integrity. It was just scale. And I felt, well, if this man could do it, I could do it too!"

Morris completed his years in Wisconsin, living on a commune, experimenting with and selling, his jewelry. When the commune burned down shortly after his graduation, he took up a friend's invitation to move to Vermont. During the long, cold winter, he taught his friend everything he had taught himself about jewelrymaking. Together they opened a small shop to provide some income.

It was a transitional period for the artist, but a valuable one. "The more I experimented, the more I felt that all that I learned from art history and studio art could be funneled into this one new medium—jewelry. It seemed that I really could make and sell jewelry. So I kept on with it until I got to a point where I was able to really start to let my personality come out in my jewelry."

This idea has continued to be one of Morris' critical, creative tenets. He feels that he has the capacity to express himself in his jewelry designs ". . . as fluently as any singer, writer or any other artist. I can express everything that I sense about the world—politics, economics, history, the relationships between cultures. All of that I am able to put into my jewelry. And it's very, very satisfying—a very good feeling. With every collection I do, I just open new doors for myself. That's why I decided to get into, and stay with, jewelry once I got going."

In 1971, Morris's work was seen by an owner of Sculpture to Wear, an exclusive gallery located in New York City's Plaza Hotel. It featured one-of-a-kind and limited-edition pieces by some of the giants of contemporary art. When he was first contacted by the gallery, Morris was not even aware that it existed. But his first encounter proved critical, for it not only crystallized his own artistic vision, but also portended his own future.

Morris speaks of being mesmerized by the work shown at Sculpture to Wear. In the jewelry designed by Picasso, Man Ray, Nevelson, Calder and Snelson, he was struck by the same level of artistic integrity that marked the work of his college sculpture teacher. "I saw that the essence of the artists' work as I knew it had been successfully translated into wearable form. And the wearable form was so much more intimate than a painting. The fact that you could caress it, wear it, sleep with it, bathe with it, made it a more immediate and satisfying art form for me. The day I walked in there, I realized that this was really 'it.'"

But he also realized something which would serve him well when Sculpture to Wear closed in 1977, and Morris found nobody else in New York willing to take a chance retailing his wildly innovative designs. "I realized that the potential was wide open. It was really exciting to think about the possibility of continuing the development of contemporary art jewelry. Many of the artists represented by Sculpture to Wear were dead or dying. I realized that we had to have new people who were not doing jewelry as an after dinner exercise, or just as a part-time off-the-cuff thing with their friends, but who were doing it as their vocation, their main direction as an artist.

Thus it occurred to Morris to open his own gallery to show both his own work and that of other young "professional jewelry artists." He was undaunted by the fact that the gallery closest to his concept had been forced to close its doors. From his contact with, and observation of, this operation, he surmised that it would have succeeded if it had had greater commitment from its owners (who lived in another city) and a truly knowledgeable and aggressive sales force. Morris was sure he could provide his venture with both.

Instead of seeing it as a major setback, Morris took the closing of his best sales outlet as the impetus for his next triumph. Taking every penny he'd saved, a $20,000 loan, and the strength of his beliefs, Robert Lee Morris opened Artwear in 1977. There were difficult times, there was struggle, there was a false start off Madison Avenue. But in August 1978, Morris finally moved Artwear to its proper and present place in the burgeoning art scene of New York's Soho district.

The philosophy of Robert Lee Morris's jewelry design and that of Artwear are nearly synonymous. He calls his work, and that of his stable—Stephan Allendorf, Cara Croninger, Douglas Ferguson, Carol Motty, Ted Muehling, Jessica Rose, Yukihiro Shibata, Sachiko Uozumi, Laurence de Vries, Steve Vaubel and Tone Vigeland—"statement jewelry." It appeals to clients who are sure of themselves, who want a strong personal look and who are not afraid of the vibrant, sculptured pieces that are the hallmark of Morris's taste. Because he manages the gallery and is often on the selling floor, he is in close touch with his customers, many of whom are creative people—even frustrated artists—with no other outlet to express themselves. They purchase jewelry at Artwear to fill this need, to find a "signature look." Customers soon learn to appreciate that the often hefty price tags do not buy gold or precious stones at Artwear. In fact they buy acrylic or bronze or rubber or silver—materials that are secondary to the fact that what the purchase really obtains is an artist's statement and the opportunity for the buyer to be personally involved with that statement.

Morris sees the designs of his own collections as a metaphoric vocabulary. His ongoing studies in cultural anthropology remain a continual source of inspiration. This is most apparent in the collection of this past year, for which he readily acknowledges the influence of North and South American and oriental cultures. Each piece becomes a kind of symbolic letter form, manipulated by him to induce an esthetic, emotional response which fits and works with previous letters. He elaborates: "When you assemble a broad group of my work, you can start to see the foundations of what might be a universal language. What fascinates me is the possibility of creating a body of jewelry that is not only timeless, but also information-giving. The hope is that when you look at my work, you don't get a sense that it is simply decorative art. The idea is to receive from it a level of information and emotion and story-telling that is not apparent in most traditional jewelry. I'm not at all interested in the decorative—I never have been. In fact, Artwear is based on that principle—that it has to have a concept—that is the foremost quality. The basic form has to have strength and meaning way before there is surface decoration. The only exception is if the surface decoration is the content and the form. But that is rarely the case."

It is usual for an art gallery to represent a group of artists whose work shares an underlying, unifying esthetic. It is more unusual for a jewelry gallery to do so, although with Morris's strong art background, it is not unexpected. What is finally startling is Morris's acknowledgment that neither he, nor his stable, were ever trained as jewelry designers. And in realizing this fact, he revels in it. It becomes a kind of confirmation that what he promotes is art in the form of body accessory. Some of his artists found their way to established career roads, and several are now called upon to teach in university programs, but none , he maintains, started out there. Thinking about it prompts some further discourse on academia.

Morris feels there is a major dichotomy between general trends and the work that continues to emerge from the university environment. It is hard to argue with his feeling that the kind of work he has been promoting has had a major impact on commercial jewelry trends. The high fashion publications—Vogue, Harper's Bazaar, Women's Wear Daily, The New York Times Fashion Supplements—have all been generously featuring his artists in editorial pages for the past six years. Certainly mass market firms like Monet and Trifari have made their own product designs bolder in response to the Artwear presence. Dut to continuing interest Morris predicts an even wider influence over the next five years. Yet, he feels the work emerging from the major schools with jewelry design programs eschews the public in favor of an academic approach. He feels students are so heavily pressured to master technique that they often forfeit an interest in, and thus an understanding of , good design. He reiterates this in his many lectures to jewelry students: "For every hour you spend learning technique, you should be learning jewelry history and jewelry design. But, in addition, you should be visiting museums, visiting not only art collections but Museum of Natural History collections. Museum of Man collections. You should be reading fashion magazines and generally seeing what's happening on the streets, in real life."

Morris makes time for these crusading efforts; he feels he has an obligation to "open up the minds of jewelry students on a much broader level than just how to make jewelry. I want them to open up their minds about what they really want to say—and then they can talk about how they want to do it."

He is genuine about the contribution he wishes to make to the development of young artists. He has found a way of combining his need to keep abreast of their work with his desire to help them. When Artwear is closed to the public on Sunday, Morris maintains an open-door policy for any designer who wishes to see him. He will offer a frank critique of their ideas. From his point of view, he finds many people who should not be making jewelry, and he will tell them so. If he finds quality work that doesn't fit his gallery, he will offer suggestions about other outlets. But if he finds people who are on the track, he will work with them, cultivate them. And of course, there are rare occasions when he happens upon "genius," and offers an artist an immediate opportunity.

Those artists who do become part of the permanent stable are now also offered the opportunity to have Morris handle their wholesaling operation. Clearly this can be in the best interest of the gallery as well as the individual, but the practice originated in Morris's response to specific requests from his exhibitors, which at first he was reluctant to satisfy. "In the beginning I wanted Artwear to be strictly like Sculpture to Wear—limited-edition, one-of-a-kind pieces and only retail. I thought wholesaling was very degrading to the image of art." But he found himself pressured by some of his own artists, who wanted to broaden their exposure and increase their sales. Since he seemed capable of doing it for himself, some of the artists argued that all parties could benefit by the centralizing of their wholesale accounts. In fact, Morris feels it took a long time for him to learn how to properly approach and sell to many sources. He actually had to help stores educate their own customers about the work, particularly outside New York. But now, their reordering is often automatic, and the wholesale sales figures rise considerably every year.

The "luck" that has come to Robert Lee Morris is hard won. The fact that he has written one million dollars in sales in the past year is due to a combination of tremendous perseverence and a great belief in his own ability and philosophy. Morris has monitored the developments of his own career, and that of Artwear, with great caution. Over the years, many opportunities have been offered to him that might have done a disservice to the Morris/Artwear image. Even when he was hungry—and there were lean years—his belief in his own concept kept him from jumping at compromising offers. Consequently, he can relate only one marketing experience which he views as a failure. This was the result of an offer to showcase his own work in New York City's successful West Side Boutique, Charivari. Morris originally seized the opportunity for several reasons. The increasingly affluent Upper West Side was a potential market that he was interested in learning more about, and, eventually, introducing to Artwear. He knew that Kansai Yamamoto was among the clothing designers carried by the store, so he felt that the clientele would be receptive to the Morris esthetic. Also, he was given a prominent window for display which allowed the use of one of Artwear's signature torso sculptures. The components all seemed right, except that Morris found out that the store didn't know how, or care to, merchandise the work properly. They never shined nor polished it, and whenever he visited his display, it was always marred by fingerprints. It was an upsetting experience, but an educational one. Morris now agrees to showcases in only the finest retail outlets such as Bloomingdale's, where he is able to maintain his high design standards.

Robert Lee Morris is a refreshingly satisfied individual. He is delighted with the niche he has carved for himself as an innovator and an entrepreneur. He speaks honestly about wishing there were others who would take the risk he did. "Competition is a really healthy thing. There just have to be more art jewelry galleries opening. If they are not opened by artists themselves, as cooperatives or private enterprises, they will be by wealthy individuals who realize that they can make a profit. I know that I could put together a list of 20 good jewelry designers that I would like to have at Artwear but just don't have the space or time to promote properly. And these artists could approach someone collectively. It's got to happen. It will just take a smart person to realize the potential and do it—to rent a space, fill the cases. I'm a good role model. People could just come here and see how I operate. All they have to do is do the same thing, and they would be successful."

Of course, Morris still makes it sound much easier than it is, but his belief in the need and value of other galleries is genuine. He is pleased that at least two others Byzantium and Detail have opened in Soho. In fact, he was instrumental in introducing the latter to New York. This evolved out of Morris's commitment to bring the work of European jewelers to the United States. He knew of the original Detail in London. Impressed with its designs, he invited the owner to put together the work of these British artists for an exhibit at Artwear. The show's immediate success here suggested that a New York-based Detail would meet with a similar reaction. Morris not only convinced the owner of this, but also actually found his Spring Street location. Detail has been there for three years, and Morris is still delighted to have such visionary competition only three blocks away.

No matter how carefully one attempts to analyze the components of a successful business, there are always factors which defy classification. In the case of Robert Lee Morris, it is likely that Morris himself provides that undefinable element—a talent, a savvy, a highly innovative jewelry design concept. But although he has broken the ground, he leaves much room for exploration and expansion by others with similar conviction and determination.

Vanessa Lynn, former art and architecture librarian at Pratt Institute and former director of the Cooper-Lynn Gallery in New York, is a freelance consultant in art and design.

You assume all responsibility and risk for the use of the safety resources available on or through this web page. The International Gem Society LLC does not assume any liability for the materials, information and opinions provided on, or available through, this web page. No advice or information provided by this website shall create any warranty. Reliance on such advice, information or the content of this web page is solely at your own risk, including without limitation any safety guidelines, resources or precautions, or any other information related to safety that may be available on or through this web page. The International Gem Society LLC disclaims any liability for injury, death or damages resulting from the use thereof.

The All-In-One Jewelry Making Solution At Your Fingertips

When you join the Ganoksin community, you get the tools you need to take your work to the next level.

Trusted Jewelry Making Information & Techniques

Sign up to receive the latest articles, techniques, and inspirations with our free newsletter.