Master Metalsmith Miyé Matsukata

15 Minute Read

When I began writing about American metalsmithing and jewelry and researching influential artists of the 1970s, the name Miyé Matsukata came up often as a jeweler who had made very rich and significant pieces using nonprecious stones, ancient coin, beach glass. In 1981, I had hoped to meet and interview her in Boston, but, unfortunately, she died a few months before my visit, and I was subsequently unable to gain access to her records.

A few years later, at a retrospective show, I saw for myself the strength of her work, but it wasn't until recently, at the urging of Margret Craver Withers, who was trying to get Matsukata's papers for the Archives of American Art, that I began exploring her stylistic development. Just who this artist was and what motivated her began to unfold as I probed her voluminous records and sketch books.

"I believed then, as I do now, that when you create art just for sale your horizons shrink, I have always believed that awareness and understanding come first, then outlets for expression present themselves."

- Miyé Matsukata, 1979

Miyé Matsukata was born in Tokyo on January 27, 1922. Although her parents were both Japanese, her father had been in government service in New York City and her mother was born and raised in Riverside, Connecticut. When her parents left the United States to return to Japan, they took with them an American teacher who became part of the Matsukata household in Japan. Miyé received the traditional upbringing of a daughter in an important household. (Her grandfather was Japanese Prime Minister Masayoshi Matsukata and a noted art collector. Her uncle Kojiro established the famous Matsukata Collection of Western Art in Tokyo.) She studied traditional flower arranging and watercolor painting, although the formal floral arrangements were often tempered with her mother's arrangements of wildflowers. She was taught formal methods of sewing, yet she and her sisters sometimes cut patterns from Vogue magazine.

The exceptional activities of the Matsukata family are exemplified by Prince Matsukata, Miyé's grandfather, who is credited with introducing Christian Science beliefs to Japan. This belief ultimately led to Miyé being sent to the American school in Japan and eventually to Principia College (a Christian Science school) in Elsah, Illinois, where she studied from 1940-44. While she was not interned, this period was not a time of easy freedom for her or any Japanese person in the United States.

After graduating from Principia, she entrolled in the Boston Museum of Fine Arts School and worked there for four years, studying metal under Joseph Sharrock. There, she received a rigorous training in classical holloware and jewelry, graduating in 1978/49 and was awarded a Travel Scholarship. She chose to go to Scandinavia (1950) and was advised by Margret Craver (then at Handy & Harman) to visit the shop of Baron Erick Fleming. She arranged to work in his Atelier Borgila for a short time. Of that experience she noted, "I tried to capture the Viking spirit and reduce the influence of the oriental style of flowing line."

Upon her return to Boston, she continued to work in the recently formed Atelier Janiyé. This shop, set up in a basement-level space at 506 Beacon Street, was a partnership with two former classmates Naomi Katz Harris and Janice Whipple Williams. By taking selected portions of their first names, the name Janiyé was created. Adding the rather pretentious "atelier" was an attempt to display both sophistication and artistic seriousness to this venture. This partnership lasted until the late 1950s, and of this period, Miyé has said:

"For the first decade-and-a-half of my career, I made almost anything—a key chain with the façade of Massachusetts General Hospital, an elephant pin for a campaigning Republican, along with the usual requests, including wedding and engagement rings.

"Then too, I tried to find a good potboiler—that something which takes the least amount of effort to produce with the minimum of time and cost, of materials, and which brings in the money so that I could have the freedom to create. I never found one. I tried mass production by having my designs made by hand in Japan and then tried to distribute by mail order.

"I sent my new creations to every museum show which invited me, I took tables at craft fairs and sold through gift shops and galleries. In point of fact, I was glued to my work bench for 15 years.

"The worry about making ends meet was constant. Though I worried, I still was able to pay the rent and supplies and to meet whatever payroll I had. Looking back, I realize that along with those artistic disciplines, I was given a sense of discipline in how to manage money."

The work of this period was almost exclusively in sterling silver and, while very competent, manifests an uncertain esthetic direction and seems to be in the mode of marketable 1950s jewelry design, as contrasted to any strong sense of artistic style or expressive intent.

The Janiyé partnership lasted until 1958, or about the time that Miyé moved to a well-lighted, second-floor shop at 551 Boyston Street overlooking Copley Plaza and the magnificent Trinity Church of H. H. Richardson—an artistic work she much admired for its form as well as its distinctive stone patterning. It was here that she worked until her maturation as an artist, jeweler and business person:

"In the late 60s I came to realize that if I wanted to sell beautiful objects, had to have surroundings of equal quality. I took out a loan and invested in adding a display room, with showcases designed and made by a wood designer, who carried out all the requirements of what by now had become my couture services in jewels. I came to see that there is an art to business, too, as well as the business of art."

In her new location Matsukata's style began to evolve. In 1962, she first began to use nonprecious materials in her pieces, ivory of mammoth tusks and petrified whale bone brought to her by a client. But it was not until she received a second Travel Grant in 1966 from the Boston Museum of Fine Arts School that her work took a decided change. While traveling to the Middle East and Greece, she became caught up with the beauty of faience and the rich color of pure gold in Egypt. At first she rejected using 24k gold in her own work, due to its softness, but after beginning to laminate it onto 18k for strength, she became captivated by it rich color.

Both her confidence and the richness of her style were growing. She received an invitation from the Yomiuri Shimbun newspaper to do an exhibit of American jewelry at the Odakyu Department Store in Tokyo. The intent of Odakyu seems to have been to show major trends in American jewelry and to create a strong consumer market for the pieces that they presumed Americans were rushing to buy. Miyé asked Olaf Skoogfors (then a professor at Philadelphia College of Art) to exhibit, but since he was Scandinavian, Stanley Lechtzin (a close colleague of Skoogfors teaching at Tyler School of Art) was also asked to exhibit to make the show more "American."

The Matsukata pieces in this 1968 exhibition were the pieces of a mature artist. Her style, vitality and confidence show in her well-known ancient Chinese bronze coin brooch. The coin with its distinct square center hole and its rich patinated surface command attention. Yet she brings her power and playful movement to the piece with the light, textured grass forms that support it. The four round diamonds punctuate and highlight the movement of the piece as well as add credibility in the eyes of the consuming public. Miyé's sensitive attitude to the commercial reality of business without compromising her artistic integrity was a highly developed strength. It is a manifestation of the Japanese attitude of respecting the forces of both beauty and power in the natural environment.

In a May 1968 interview in Japan, Miyé articulated her views, which are evidenced especially well in the coin piece: "I would like to maintain a spirit of design that is quiet and free. I feel metal can have a life if it has motion and less rigid confines." Her pieces of this period had no boundaries other than stone bezels and many of the forms, such as the cover photo of the catalog, seem to be frozen moments of motion highlighted by a precious stone, series of beads or pieces of beach glass.

In the piece using the Egyptian Pharonic tube beads, she displayer her control of motion by allowing the beads to tumble into space and then capturing them quickly with thin, light, 24k gold wrappers. Additional tube beads of gold complete the sensitive harmony of movement. Even the prongs holding the round faience beads appear quick and spontaneous. The rigidity of the metal seems to vanish because of the respect she displays for its nature and qualities—as though she is one with the metal and exerts a control over it that harmonizes perfectly with its characteristics.

The flowing oriental line is indeed gone from her work, but the sensitive spirit "Sekitei," rock garden arrangement, manifests itself in a unique purity. Years of work and a willingness to look closely at her surroundings as well as at the beauty of ancient cultures had been filtered through intellect and emotion to make a statement that was new and much appreciated by young artists at the time, such as Eleanor Ebendorf (State University of New York and New Paltz), who found their way to her studio.

Miyé Matsukata had an infatuation with stone. She grew up with it and she respected it. From her mother's sixth floor apartment in Tokyo she could see the stone wall of the Nezu Art Museum on the south and the head stones of the Aoyama cemetery on the north. She admits conscious inspiration from her visits to the pyramids of Egypt, the amphitheater at Epidarus, the Mycenae grave sites, the Gorome valley in Turkey and Machu Picchu in Peru. Not only did she use a variety of chasing tools to achieve the texture of stone, but also she often literally lifted the quality of surface from the stone itself as the thin sheets of gold accurately registered a varied surface.

In the Haystack piece, light, hammered gold sheets imitate large stone forms. Diamonds representing small stones are set between the large. The Japanese call this type of stone wall "Gobo Mori." "Mori" meaning piled up and "Gobo" an edible brown vegetable root with a round stem.

This appreciation for stone was articulated and emphasized by her association with a knowledgeable and talented stonecutter James Hubbard, who eventually became her business manager and agent. Hubbard's exacting knowledge of stone as well as his sensitivity to its nature blended well with Matsukata's own reverence for the material. In a lecture entitled "The Legacy of Stone," she states:

"Stone has given me a rich legacy of TEXTURE, FORM, COLOR and COMPOSITION.

. . . If texture represents character of surface as distinct from form and color, then my pieces borrow some textural elements direct from the stone itself.

. . . The stone-like rough surfaces, I use in patches of pure gold have become the trademark of my Atelier Janiyé."

She showed a reverence for the knowledge and sensitivity of the stonemason:

"Standing in front of a teacher such as this stone wall, I see how one shape is balanced upon another . . . . Now shaping and fitting each piece are what I do as I build a ring form the ground up."

Miyé often reffered to her pieces as painting-sculptures. She explains:

"The idea emerges first as a two-dimensional sketch. But when they are made, or constructed, I have to decide how the line reads into a three-dimensional expression which encases space and catches light on an uneven surface. This is sculpture."

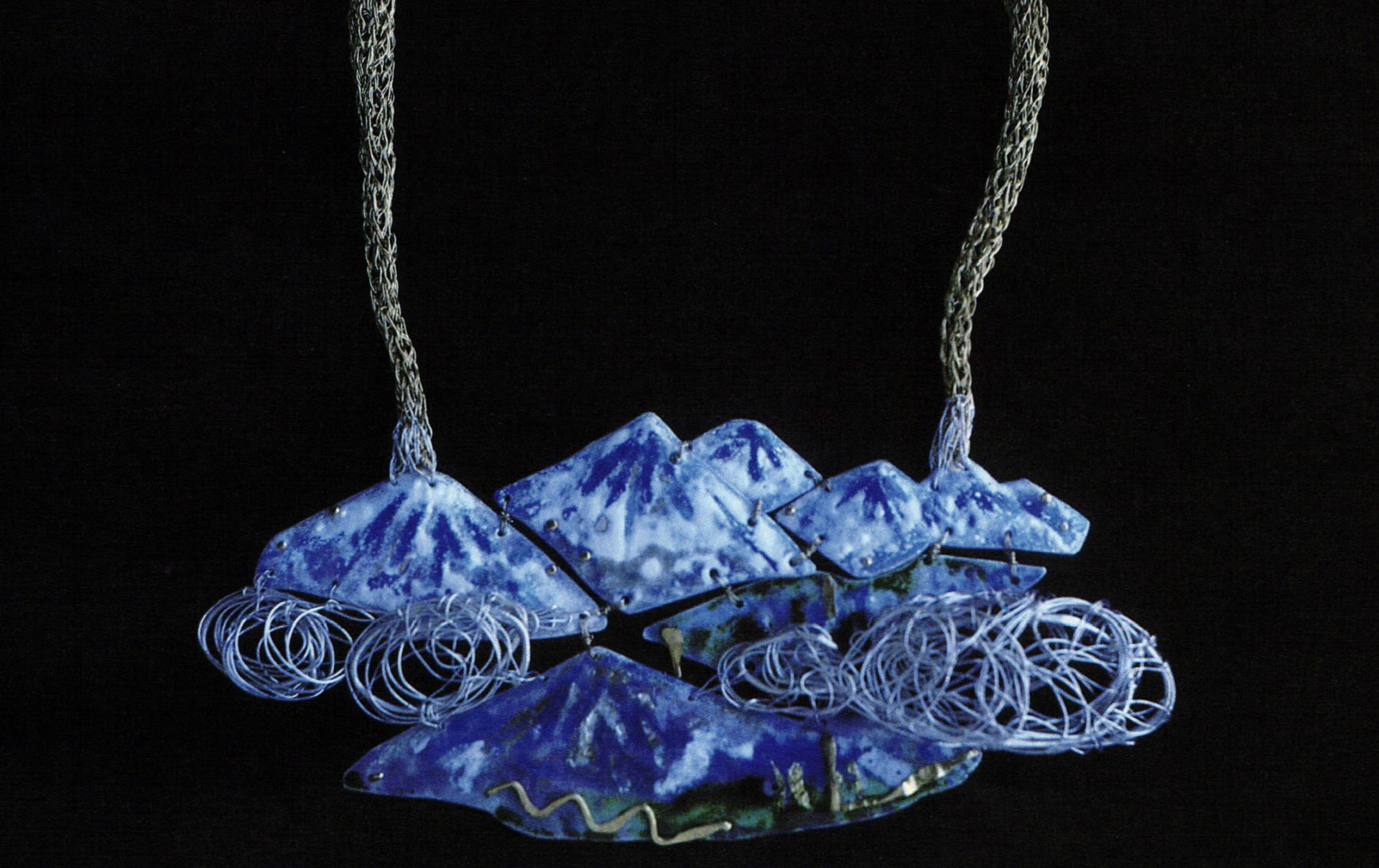

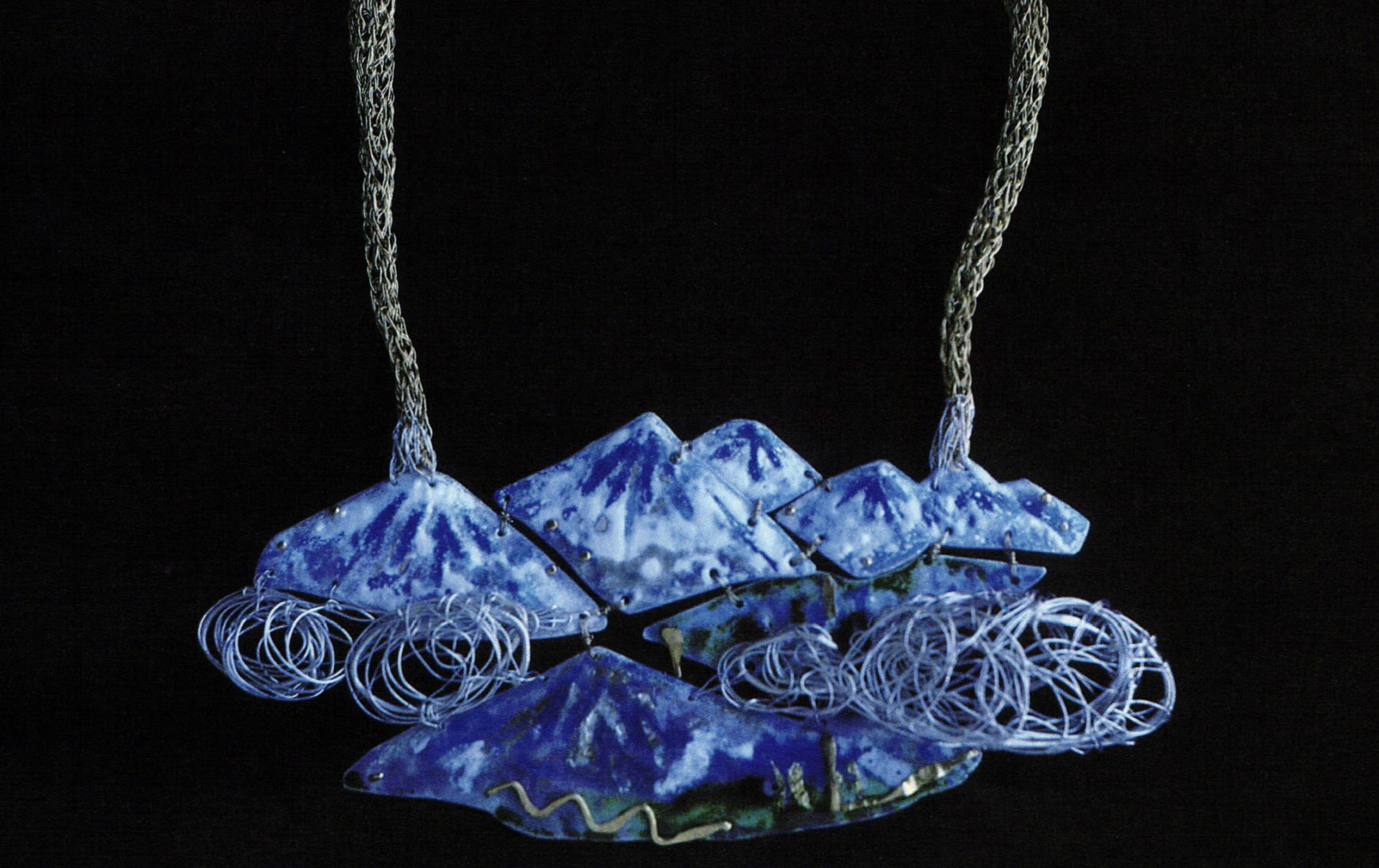

Matsukata also explored enamel both in rings and in a series of large gorgets. She makes mention of studying briefly with the noted enamellist William Harper (Florida State University at Tallahassee), although she added that she followed none of the rules of enameling. The gorget pieces, which although somewhat coarse in technique and color control, possess a powerful statement. She recorded in some 12 pieces the impressions of her beloved Boston throughout the seasons, taken from dozens of slides and sketches of the city she made at various times and lights.

<

p style="text-align: justify;">The enamel neckpieces set the stage for works of much larger scale. In her work of the early 1980s, Miyé was moving in the direction of more monumentality by using large stones—many cut by Hubbard—or large single pieces of metal, and even framed pieces of antique Chinese silk brocade. She also made good use of her love of fiber techniques and the tutelage of Arline Fisch, in her large "crocheted" neckpieces. Her study with Fisch took place while Arline was teaching at Boston University in the mid-1970s. The pieces display a loose handling of the fine silver wire and avoid rigorous woven metal patterns. The necklaces themselves are 20 to 24 inches in length, with some sections nearly one inch in diameter. Fresh water pearls, stone or ancient glass beads and even patches of silk thread are sewn spontaneously into them.

Both the enamel and the fiber techniques freed Miyé from the rigorous training she had undergone with Sharrock at the Boston Museum School. She was finally able to work without the rigor demanded of totally fabricated pieces, and more importantly, she was able to literally grab swatches of color and boldly lay them onto or collage them into her work. The pieces have great vitality and courage of form and color. Some pieces actually became clothing forms such as full collars, using more cloth than metal in the composition.

While Miyé was not an academic, she did teach several sessions at Haystack Mountain School of Crafts in Deer Isle, Maine, as well as participating in early meetings and exhibitions of the Society of North American Goldsmiths. She also employed, taught and shared ideas with a number of fine Boston-area artists: Babro Ulander, Yoshiko Yamamoto (Boston Museum School), Alexandra Solowij Watkins and Nancy W. Michel. Watkins and Michel continue to operate Atelier Janiyé in Boston and to produce work in the spirit of Matsukata as well as their own fine pieces.

Her personal impact is most clearly felt in Boston, and the hundreds of pieces she produced are beginning to find their way into major museum collections. The legacy she left is related to her rich and unique interpretation of the Japanese esthetic, most importantly revealed in the reverent ways in which she used nonprecious stones, coins, fabric and even beach glass in her painting-sculptures. Her commitment to placing idea and the richly textured lessons of stone ahead of her desire to sell has handed on to us a bold and vital legacy in a body of work that manifests the same powerful qualities of the massive stone monuments so admired by this gentle woman.

References

- "The Design Speaks," Charlotte Saikowski, The Christian Science Monitor, May 20, 1968, p. 10.

- "It has a familiar ring to the brides of today," Carol Osherenko, The Christian Science Monitor, May 26, 1969, p. 6.

- "The Art of Miyé Matsukata," Miyé Matsukata, The Christian Science Monitor, July 30, 1974.

- "Mountains, bird inspire 'wearable sculpture," Debra K. Piot, The Christian Science Monitor, April 9, 1980.

- "Jewelry with Soul, A Review of The Jewelry of Miyé Matsukata: A Retrospective Exhibition 1951-1981, "Boston Athenaeum Gallery, Christine Timen, The Boston Glove, February 17, 1982, p. 64.

- "The Legacy of Stone," unpublished, undated lecture by Miyé Matsukata.

A special note of appreciation and gratitude goes to Mrs. Ann Gaddis, the sister of the late James Hubbard, for making the many photos, sketches and notes available for this article. Without her generous cooperation, the sharing of the work Miyé Matsukata would not have been possible.

Robert L. Cardinale, former Director of the Program in Artisanry at Boston University (now at Swan School of Design), was named President of the San Antonio Art Institute in San Antonio, TX, in January of 1986.

You assume all responsibility and risk for the use of the safety resources available on or through this web page. The International Gem Society LLC does not assume any liability for the materials, information and opinions provided on, or available through, this web page. No advice or information provided by this website shall create any warranty. Reliance on such advice, information or the content of this web page is solely at your own risk, including without limitation any safety guidelines, resources or precautions, or any other information related to safety that may be available on or through this web page. The International Gem Society LLC disclaims any liability for injury, death or damages resulting from the use thereof.

Related Articles

Master Metalsmith Dorothy Sturm

From The Bench: Kohler Company

Subtle Form of Seduction

Global Village of the Design Elite

The All-In-One Jewelry Making Solution At Your Fingertips

When you join the Ganoksin community, you get the tools you need to take your work to the next level.

Trusted Jewelry Making Information & Techniques

Sign up to receive the latest articles, techniques, and inspirations with our free newsletter.