Master Metalsmith Harold Stacey

19 Minute Read

Growing up in the house of a silversmith is an unusual experience, the more so if the place where one spends one childhood is a typical North American suburb, vintage early 50s, where one's friends' fathers drive to normal nine-to-five jobs in offices and factories and their mothers are content to be housewives. The very reverse of the parental roles—father staying home to work, mother, a teacher, going out—was enough to set our family apart.

But it was more what my father actually did that made us unusual not only in our neighbours' eyes but in our own. We—my sister and I, and our long-suffering mother—were marked by the nature of his vocation as permanently and unmistakeably as the burnished, glittering objects that emerged, one or two a year, from this domestic Fafnir's cave, their bases bearing the incisive impress of that tiny national mark for sterling silver, the heraldic British lion's head in a capital C, bestraddled by the registered trademark "STACEY STERLING." It was a badge of possession no less than a guarantee of quality of materials and workmanship: by definition, those gleaming treasures—and that much-needed tableware—on which it appeared could never belong to the likes of us. The old story, as my mother was given to sighing, of the cobbler's children. . . .

The difference—the strangeness—that set us apart, at least in my boyish imagination, was announced and punctuated by the daylong (and sometimes nightlong) din that arose from our incredibly cluttered basement, which my father had converted into a workshop in contravention of the residential zoning laws. When I try to picture what it was like, I listen rather than look for the signs that identified the arcane calling of the hammerer below whacking monotonously away at the paraboloid bowl being raised out of malleable flatness of the rounded stake. Bangbang-BANG, bangbang-BANG!—a rarely varying tattoo that penetrated the first and second storeys, filled the walls with steady metallic ringing, echoed in sleep long after the barrage had ceased in the small hours of the morning.

This is not a lament for Harold Stacey, but rather a celebration. His death in March, 1979 deprived Canada of one of her ablest and most dedicated artists in metal. His reputation, firmly established among older members of his profession, would be greater were it not for his aversion to hype and the traditional indifference to the applied arts that is endemic throughout North America. The versatility of his gift enabled him to work in a wide variety of metals—notably silver. gold, copper, brass. bronze and pewter—as well as for a remarkable range of clients. This factor ensured that his pieces, however little he may have realized from them in terms of renown or remuneration, fulfilled their promise of enduring utility—something the fabrications of only a handful of his colleagues could be said to possess.

Stacey's specialties can be grouped into four major categories: domestic (flatware, holloware); ecclesiastical (everything from chalices to processional crosses, tabernacles to sanctuary lamps); jewellery and accessories (with and without stone settings, semiprecious minerals being his preference); architectural constructions; and miscellaneous (trophies, ceremonial maces and the like). Whatever the material and whatever the application, Stacey tackled his task with a single-minded perfectionism that was sometimes frightening. The more obdurate the material, the grimmer his determination to bend it to his will—without, however, doing violence to the intrinsic: nature of either the agent or the object. The result, when inspiration accompanied technical mastery, was a statement of the essence of the substance itself, the message of form expressed in the medium of metal. Silver above all he loved, gold second; these two alone were paired with his surname of his final-touch stamps.

The grateful testimony of Stacey's many students attests to another ability to which not all crafts professionals can boast: the skills of a sympathetic, patient, but demanding teacher—one who, incidentally but revealingly, hated teaching and did so only out of economic necessity. Once committed to a task, however uncongenial it might have been to his spirit, he carried it through with scrupulous integrity.

The son of a laboratory chemist from South London and a former school teacher and newspaper reporter of Irish extraction from the Eastern Townships of Quebec, Harold Stacey was born in Montreal in 1911. He grew up there and in the city of Sherbrooke before moving with his family to Toronto, where he was to spend most of his working life.

To the question of how he first got involved in silversmithing, Stacey replied that he had always liked working—not with his hands, or with implements, so much as with materials. Initially he experimented with wood, which he found too unstable for his purposes, so he switched to metals. As he told a journalist in 1968, "Wood has a tendency to swell or shrink according to the weather. You know metal won't change." He liked the precision of metal, and in manipulating it he experienced what he called "the joy of construction and of changing shapes."

His first encounter with the tools associated with his métier occurred in his mechanical training classes in Montreal. Then the Depression—Stacey was the eldest of five children—forced him, like so many of his generation, to leave school and seek work to support his family. One of his first jobs was in a picture-framing shop in Toronto. From 1929 to 1932 he worked for IBM servicing their equipment. This involved fine adjustment and assembly, and proved helpful in developing his dexterity and accuracy of judgment. His formal introduction to his future craft took place at Toronto's Central Technical School, where his industrial arts instructor, Frank Izon, started him on metalwork.

By this time his hobbies included the making of bracelets, ashtrays and trinkets. The Canadian Handicraft Guild's new shop at the prestigious Eaton College Street store provided him with an outlet—as it did for silversmiths Andrew Fussell and Douglas Boyd, and sculptor E.B. Cox. Stacey decided to go into silverwork full time in 1932 because he did not want to make, as he put it, "eighteen cents an hour working for someone else" when he could make "fifteen cents an hour" working for himself. He chose to concentrate on affordable, nonprecious, nonferreous metals such as pewter, brass and copper. Silver then cost around 50 cents (Canadian) an ounce; then as now, gold was prohibitively expensive.

The first great influence on Stacey's stylistic development was the Swedish metalsmith Rudolph Renzius, who set up a studio and workshop in Toronto's Gerrard Street "Village" in the early 30s. His specialty was pewter work, "Britannia metal," then being popular as well as cheap. In 1932-33 Renzius taught night classes at Northern Vocational School (now Northern Secondary), and during 1934-35 at Central Tech. Stacey described his own early abilities as the products of "instinct"—a natural acumen or expertise involving imagination as well as technical aptitude. Renzius helped to turn the autodidact into a professional. After "Rudy" stopped teaching in 1935, Stacey took over his evening classes at Northern and Central until 1940.

In 1936 he met another mentor who was to confirm the direction of his career: Douglas M. Duncan (1902-1968), the independently wealthy connoisseur and bookbinder who founded the Picture Loan Society, the first such facility to be established in Canada. Stacey happened to be putting on a jewellery-making demonstration at Eaton Auditorium, in the College Street store; Duncan came up to his workbench, asked him a few questions and finally offered him a studio in his "hovel" at the corner of Toronto's St. Mary's and Yonge Streets. Later Duncan and his artist-tenants moved into the top floor of the building on the southeastern corner of Yonge and Charles, where the Picture Loan Gallery was opened and where Alan Jarvis (later director of the National Gallery of Canada) had a sculpture studio. David Milne, arguably Canada's greatest painter, had a workroom just down the hall.

Heady as such a creative milieu must have been for a young and unsophisticated novitiate in the arts, Stacey, never a "joiner," felt estranged from the rather self-consciously bohemian cultural community that swirled so busily about him. Nevertheless, he remained deeply grateful to Duncan for his support and encouragement, without which he might never have been able to concentrate on perfecting his exacting craft.

Stacey stayed at the Picture Loan building for six years. In 1940 he was hired by the electronic development laboratory of Research Enterprises, Leaside, which produced top-secret radar equipment. He got the job by virtue of his skill in constructing intricate metal devices and forms; before long he was promoted to the position of supervisor of the radio engineering model shop, clocking 72-hour weeks. Although he put himself forward for overseas service, his application was turned down on the grounds that his skills were needed for the critical home-front war effort. In 1941 Stacey married Margaret Jefferys, daughter of the eminent Canadian historical illustrator and landscape painter C.W. Jefferys (1869-1951).

The war over, Stacey was invited to teach at the Ontario College of Art by Jefferys' old confrère F.H. Brigden, who was on the OCA's Board of Directors. There he remained as Instructor of Metalworking and Design Techniques until 1945. While still at OCA he had reopened his private studio for the production of custom-designed architectural and liturgical metalwork. By this time his main interest was in sterling, pewter having been withdrawn as a strategic metal during the war. There was plenty of work to be had, but, as he explained to the writer of a Mayfair (A Canadian "society" publication of the Better Homes and Gardens variety, no relation to the American skin-mag!) magazine article on him, published in May, 1951, he was forced to wind up his Toronto firm because he "despaired of ever being able to handle the business offered him." The two impediments that had beaten him were l, "the records, forms and reports which governments now force the small businessman to keep," and 2, "his inability to offer his employees free medical care, pensions, baseball uniforms and the like."

These typical disadvantages of small proprietorship meant that he could not compete with larger industries for the services of skilled artisans. "It is significant in these times, Mr. Stacey believes," continued his interviewer, "that the joy of creating beautiful things no longer compensates for devoted efforts. Craftsmen, or what are called craftsmen (especially the younger generation), are interested in the greatest material security they can obtain in return for the least possible expenditure of time and attention." This, too, was to remain a sore point with Stacey throughout his teaching and working days.

The incident that prompted his decision to try his luck in the United States was the abrupt cancellation, in 1950, of a Department of External Affairs commission to design a flatware pattern for use in Canada's foreign embassies and consulates. His confidence in making the move had been bolstered by the invitation, in 1949, to study at the Rhode Island School of Design, where Baron Erik Fleming, Silversmith to the Swedish Royal Family, was conducting a summer workshop sponsored by Handy and Harman. Of the Baron's 15 students, Stacey was the lone Canadian.

The purpose of Fleming's course was to introduce to North America the old Swedish method of forming and raising silver bowls and vessels featuring pronounced edges. This procedure involved not only the adding of metal to build up the edge, but the use of thick silver sheets that are beaten to a degree of thinness except for the rim. "It gives an effect of great richness and quality," Stacey was quoted as saying. "Wonderful, though expensive." Exemplifying the Fleming method is a raised silver bowl by Stacey that was purchased by the U.S. State Department as part of a collection of contemporary American silverware for circulation in Germany. It was included in the 1950 "Hand-Wrought Silver" exhibition organized for the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York by Margret Craver, head of Handy and Harman's education department (figure 2).

Although Stacey was attracted by aspects of his Rhode Island experience, he was distressed by what he described as the "never-neverland unreality of small American colleges, which produce students whose main aim is to obtain a teaching post." Stacey the teacher-craftsman saw himself as "helping to train people to earn a little money out of what they are doing." The world of work, not academe, called to him. At the conclusion of one of the Handy and Harman workshops, held in Rochester he turned down the offer of a teaching post there in favour of the position of supervisor of the silver design research model shop at the Steuben Crystal Divison of Corning Glassworks Ltd. in New York City. His task was to develop a line of high-quality flatware. However, eventually Steuben concluded that diversification into silverware would prove economically unfeasible. Stacey felt himself to be under unfair pressure to make a commercial success of an untried product when he had in fact been hired only as a consultant—one of the disadvantages, as he expressed it, of "research-sinecureship."

A positive aspect of his New York sojourn was the proximity of museums and galleries, which broadened his taste and introduced him to schools of design and craft of which he had been only dimly aware in Toronto. At Corning he also met a brilliant Swedish-born silversmith, Solve Holquist, whom he hired to assist him on the Steuben project, and with whom he was later to form a professional partnership in Toronto.

Once reestablished in Canada, Stacey went into metal product design and development on a freelance basis with several firms, including Massey-Harris Ltd. (now Massey-Ferguson), the farm-implement manufacturer. Such assignments brought him into daily contact with engineers and architects. Collaborating with these specialists provided him with a first-hand knowledge of structural and environmental problems, which were increasingly put to use as his commissions became larger in scale and involved outdoor as well as interior installation.

From 1956 to 1960 Stacey conducted Ontario Department of Education summer courses for teachers specializing in Industrial Arts, and until 1968 operated his own studios for design and production of metalwork for liturgical, architectural and ceremonial purposes. Solve Holquist joined him in the early 60s and collaborated with him on a number of important jobs, while producing his own line of fine sterling jewellery. Vickers Head, an English-born metal-craftsman, worked for Stacey until 1968.

In that year came Stacey's appointment to the position of Instructor of Metal Arts Furniture Accessories at Humber College, a multicampus community college in Metropolitan Toronto. He remained at Humber, eventually as head of Environmental Metal Arts and Continuing Education Coordinator of the Creative Arts Division (Hero Kielman, Chairman), until his retirement in 1975. In some ways these were disappointing years for the artist. His return to the educational field came at an unfortunate time. Publicly funded institutions laboured under the officially mandated delusions that native talent was by nature inferior to the imported variety. American, British and European teachers and administrators were favoured for top jobs as a matter of course. Once at Humber, Stacey found that creativity had to be subordinated to the ceaseless demands of administrative chores and paperwork. Great, then, was his delight whenever he encountered that increasingly rare phenomenon, a pupil who combined native creativity with a desire to persevere, a sense of discipline and a willingness to listen.

One complaint voiced by his charges was his reluctance to put himself forward, either in the demonstrating of his own methods or in talking about his own work. He rarely exhibited and further deprecated the kind of fancy showpieces that tended to be featured in the highly competitive annuals of crafts associations and college departments. This reticence stemmed partly from a feeling that too many so-called silversmiths had strayed from the high road of truth-to-medium and formal functionalism. Having survived the Depression, Stacey had little patience with dilettant colleagues who relied on grants, sinecures and artist-in-residenceships for their livelihoods. Far too many of the professors of fine crafts whom he encountered were content to teach and preach rather than practise in the real-world marketplace, and as a consequence were too preoccupied with theory and too little concerned with the practicalities of the business to be able to offer the neophyte either the fruits of experience or the working philosophy of "the art spirit."

A purist as well as a procrastinator (hence the numerous deadline crises), Stacey nevertheless warned against the precious isolationism of the handicrafts ivory tower. He understood the necessity of compromise and cooperation. "The craftsman," he argued, "must realize he can't work entirely by himself. He's got to be willing to work with people, architects, artist or other craftsmen." Stylistically, Stacey was a product of the 1930s and 40s. One of his first international influences was art moderne, the term he preferred to art déco, which he viewed as a fashionable vulgarization of an elementally austere and practical mode. Later he was affected by the recently introduced "Scandinavian modern" approach, which for several decades set the tone in virtually all branches of the metal arts. His own mature esthetic emphasized clean, uncluttered lines and plain but highly burnished or planished surfaces.

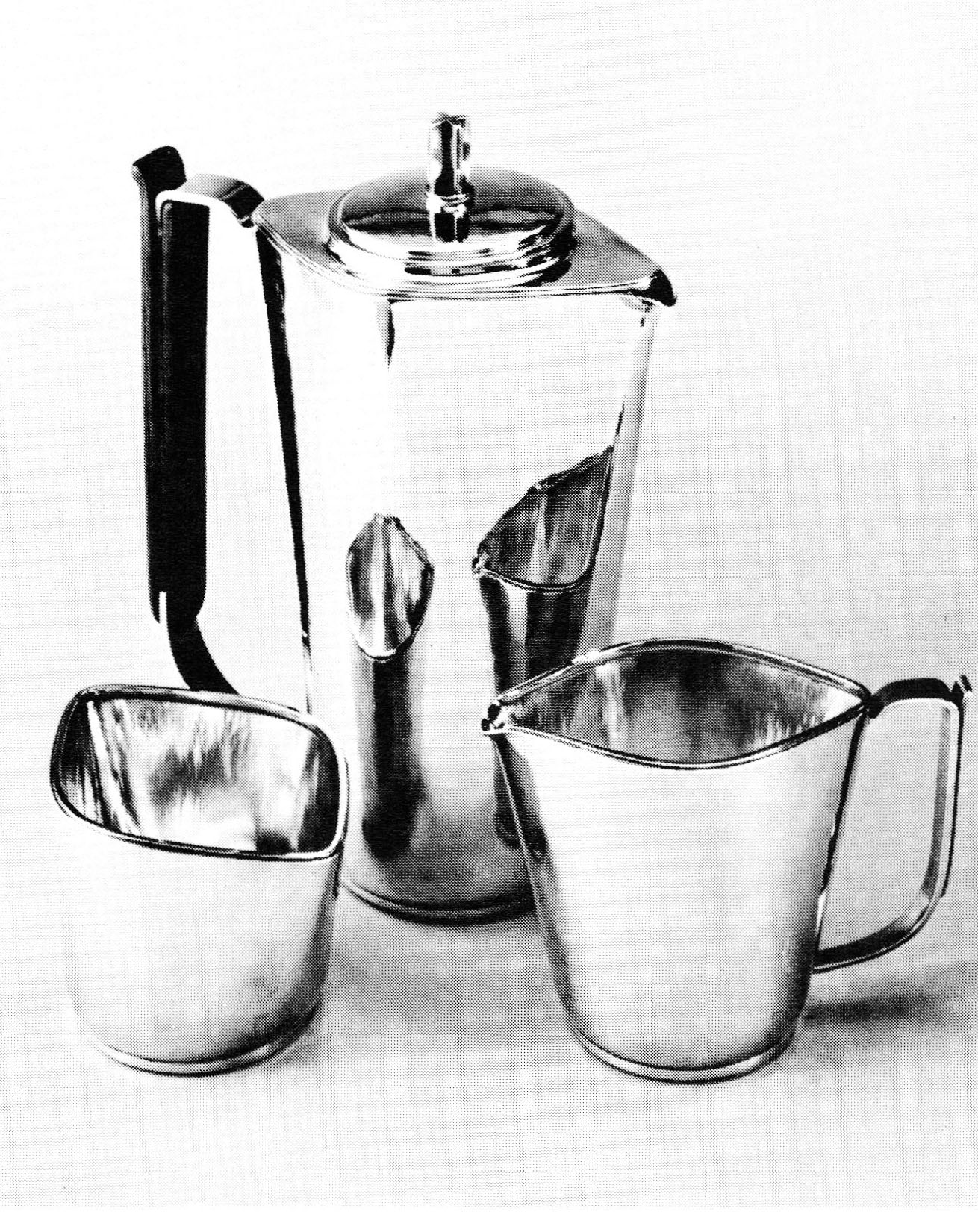

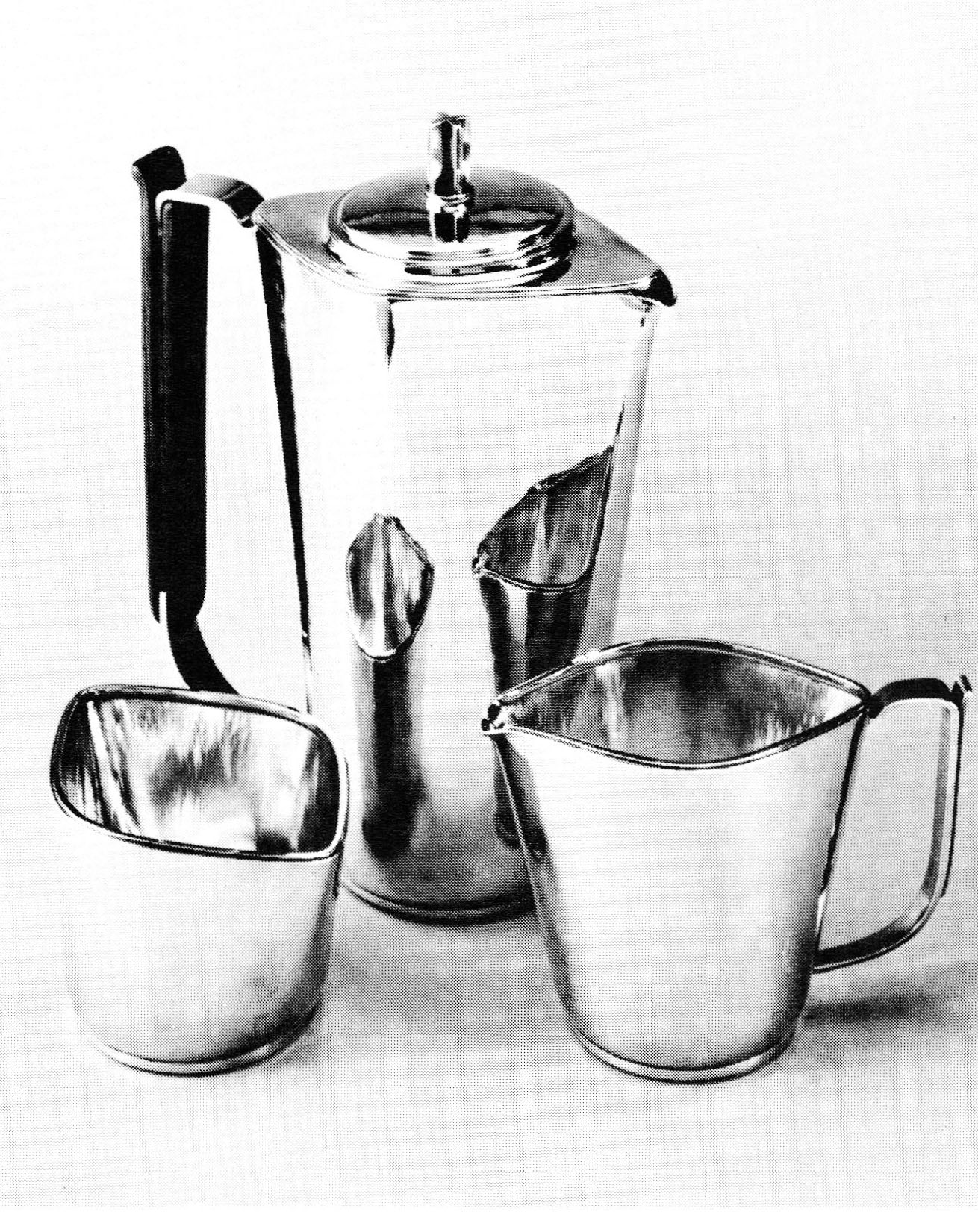

Perhaps the most noteworthy illustration of this manner is the sterling silver coffee service commissioned in 1950 by Douglas Duncan, which appeared in the 100th anniversary exhibition of the Ontario College of Art, mounted at the Art Gallery of Ontario in 1976 (figure 3). As Jeanne Parkin observed in Crafts Canada (Dec. 1976-Jan. 1977 issue) of this "particularly outstanding piece": "Its simplicity and elegance—expressed through the artist's sensitivity to shape, form, proportion and surface—has made this an example of truly classic beauty which has withstood the test of time, and one that demonstrates the kind of standards which we are searching for in establishing a tradition fo design excellence in this country."

Just as his many religious and institutional commissions attest to the agnostic Stacey's description of himself as an "ecumenical craftsman," so his imaginative flexibility allowed him to accommodate his tastes and precepts to the requirements of the task at hand. Thus, if a more traditional approach were called for, he could come up with a design that would be appropriate to the occasion and the use of the object and yet express the salient characteristics of his style. Examples of this adaptability are the grace cup and great salt (figure 4) he designed and crafted in silver for the dining hall of the University of Western Ontario's Somerville House in 1957. In the words of Toronto Globe and Mail art critic Pearl McCarthy, "These are fine examples of Mr. Stacey's high standard. Since the ideas involved were traditional, he designed them with traditional feeling, though not as copies of any period pieces." His models were the salts and grace cups of the Stuart period, which he considered to be both the most typical and interesting examples of 17th-century silverwork. The Royal Ontario Museum's Helen Ignatieff, in her Canadian Antiques Collector (May, 1971) article on Ontario silversmiths, remarked that Stacey, "in following this tradition"—i.e., that of the court orfèvres of the English Renaissance—"has made a notable modern form. The strength of the salt, the elegance of form and sophistication of design are worthy of the highest regard and recognition in the history of Canadian silvermaking."

It was not so much the frustrations of teaching as the dawning awareness that economic survival for the self-employed craftsman in Canada was a virtual impossibility that led Stacey to join four other interested individuals to form the Metal Arts Guild in 1946. Among the "purposes and objectives" of the Guild, as stated in its petition for letters patent, was the promotion and encouragement of "the cultural and commercial development of metal arts and crafts both ferreous and nonferreous." Of all the Guild's bold 12-point programme, perhaps only a handful of goals were actually achieved in Staccy's lifetime, but the establishment of the society was itself a significant step in the on-going struggle for recognition of the applied arts and crafts in Canada. Among Stacey's major secular pieces is the George Steel Trophy (1958), "Named in honor of George Steel whose interests in the artistic beauty of Canadian stones and metals gave pioneer impetus to the Metal Arts Guild" (figure 5).

As he became more heavily involved in teaching and his own work, Stacey withdrew from active participation in associations such as the Guild, the Ontario Crafts Foundation (of which he was a founding member and a director), and the Society of North American Goldsmiths (on whose board he sat). He did, however, freely dispense advice and counsel to those who sought it, if he deemed them sincere and willing to make sacrifices for their work.

Like many publicity-shy people of cynical bent, he complained at times of being overlooked, though had he been capable of self-promotion the acknowledgment (and the reasonable fees) would eventually have come his way. Too late to alter this old pattern was the receipt of the Canadian Crafts Council's special category of Honourary Membership, awarded for outstanding services to the crafts in Canada. Representing the art of silversmithing (as British Columbia's Bill Reid did goldsmithing), Stacey accepted this honour and its accompanying trophy in 1976, the year of the award's debut, and the 30th anniversary of the official certification of "STACEY STERLING."

One of the most cogent assessments of Stacey's place among contemporary Canadian—and, one would like think, North American—silversmiths appeared in the unsigned 1951 Mayfair magazine profile quoted above: "In describing Mr. Stacey as 'foremost creator,' [of individually designed household silver' in Canada] the writer of these lines is expressing a critical opinion. There is no Oscar to establish who's tops among the metalsmiths of Canada. In almost every city there's a leading jeweler who'll take your order for custom-made flatware or holloware. But Montreal-born Harold Stacey has put himself in the front rank by expressing his own concepts of beauty. He is dedicated to no school or period; he strains for no radical effects, no self-conscious modernism, no tortured originality. . . . With a true artist's individuality he has construed grace and beauty in his own terms, insisting always on forms appropriate to the purpose for which it is designed and made. When the whole story of the Stacey career is eventually told, it will be seen that his preeminence has extended well beyond the borders of Canada."

A premature prediction, no doubt, for 1951. But precious metal outlasts fashion, as does craftsmanship. The record is there for appraisal, though the whole story is still far from being told.

Robert Stacey is a freelance art historian, exhibition curator, writer and editor, who lives and works in Toronto, Canada. He gratefully acknowledges the assistance of his sister, Clara, in the researching of this article.

Note: This is a substantially revised version of an article on Harold Stacey published in Canada Crafts, Jan./Feb., 1980.

Clara Stacey, the artist's daughter, has embarked on the project of cataloging all of Stacey's work, as the first step toward an eventual monograph or exhibition catalog. She would be grateful to receive information about pieces in private, public and institutional hands, as well as copies of correspondence and other documents pertaining to Stacey's career and reminiscences of his colleagues and friends. Her mailing address is 122 Bowood Ave., Toronto, Ontario, M4N 1Y5, Canada.

You assume all responsibility and risk for the use of the safety resources available on or through this web page. The International Gem Society LLC does not assume any liability for the materials, information and opinions provided on, or available through, this web page. No advice or information provided by this website shall create any warranty. Reliance on such advice, information or the content of this web page is solely at your own risk, including without limitation any safety guidelines, resources or precautions, or any other information related to safety that may be available on or through this web page. The International Gem Society LLC disclaims any liability for injury, death or damages resulting from the use thereof.

Related Articles

The Holloware of David Huang

Ambiguous Visions of Louise Norrell

Mac McCall: Wizard of Ambiguity

Pforzheim University: Reflecting Reality and Creating an Identity

The All-In-One Jewelry Making Solution At Your Fingertips

When you join the Ganoksin community, you get the tools you need to take your work to the next level.

Trusted Jewelry Making Information & Techniques

Sign up to receive the latest articles, techniques, and inspirations with our free newsletter.