The Life and Times of J. Fred Woell

14 Minute Read

Fred Woell's spirit was born in and of the sixties. His molten slogans register, graffitt-ilike, upon the collective "wall" of his pins and reliefs. One reads these signs as transcribed symbols of our debased culture. His visual rhetoric bred of indignance unveils the forces of ersatz consumerism, that reside in fast food palaces and travel the interstate, that peer at us from television and billboards, that clothe our heroes, our religions and our politics, and that destroy our landscape, our cities and our souls.

With wit intact, he emerges triumphant from the active engagement of its symbolism. For his goal is no longer for the cultural myth to be unmasked. The symbol itself must be shaken.

A Picaresque Tale

Back in the late 60s, when most of academia was finding a spot on the barricades, Fred Woell was in his mid-30s finding his way around Frank Gallo's studio or the sculpture department at Cranbrook.

Woell's life up to then had been a picaresque tale. After college came the perfunctory stint in the U.S. Army. Two inspirational years at the University of Illinois studying under Robert von Neumann was closely followed by an M.F.A. in art, metal and graphics from the University of Wisconsin, Madison under Arthur Vierthaler. An early rejection of the "gold standard" in jewelry, Woell's first Pop piece entitled Lincoln for President, using his father's old wristwatch, was accepted into the 1963 annual Wisconsin Designer/Craftsmen show at the Milwaukee Art Gallery. As if to slat Woell's callous disavowl of "precious" tradition, a Scandinavian Modern silver piece was awarded the grand prize.

Hope springs eternal. Woell ventured East, looking for a warmer reception and lured by the sweet smell of the 1965 "Art of Personal Adornment" exhibit at the Museum of Contemporary Craft. But further rejection awaited him in New York City, as the jewelry "establishment" snubbed his Pop jewelry—a philistine gesture, an affront to his raw creativity.

Disillusioned, Woell sought the haven of rural Wisconsin, where he led a Walden-like existence, searching for the center, the Zen, John Cage's silence, trying to reconcile the rebellious attitude that was determined to create what was deemed unacceptable. Reality arrived at his doorstep in the guise of a broken-down car. Needing the cash for an overhaul, Woell was back in Illinois, seeking help from friends like von Neumann, sacking out in cheap university flats, waiting on fraternity tables and wangling his way into the fortuitous protection of Gallo's studio, where he apprenticed from 1965-67.

A Ruminant in the Round

Gallo was already established as a Pop Art sculptor noted for his satire of "cocktail culture." His signature epoxy-resin figures portrayed clinical eroticism and a penetration of contemporary anxiety. Gallo's unique sensibility was not one of ridicule but of empathy, bordering on pathos. It was in Gallo's studio that Woell found the tenor of optimism in his search for socially relevant art.

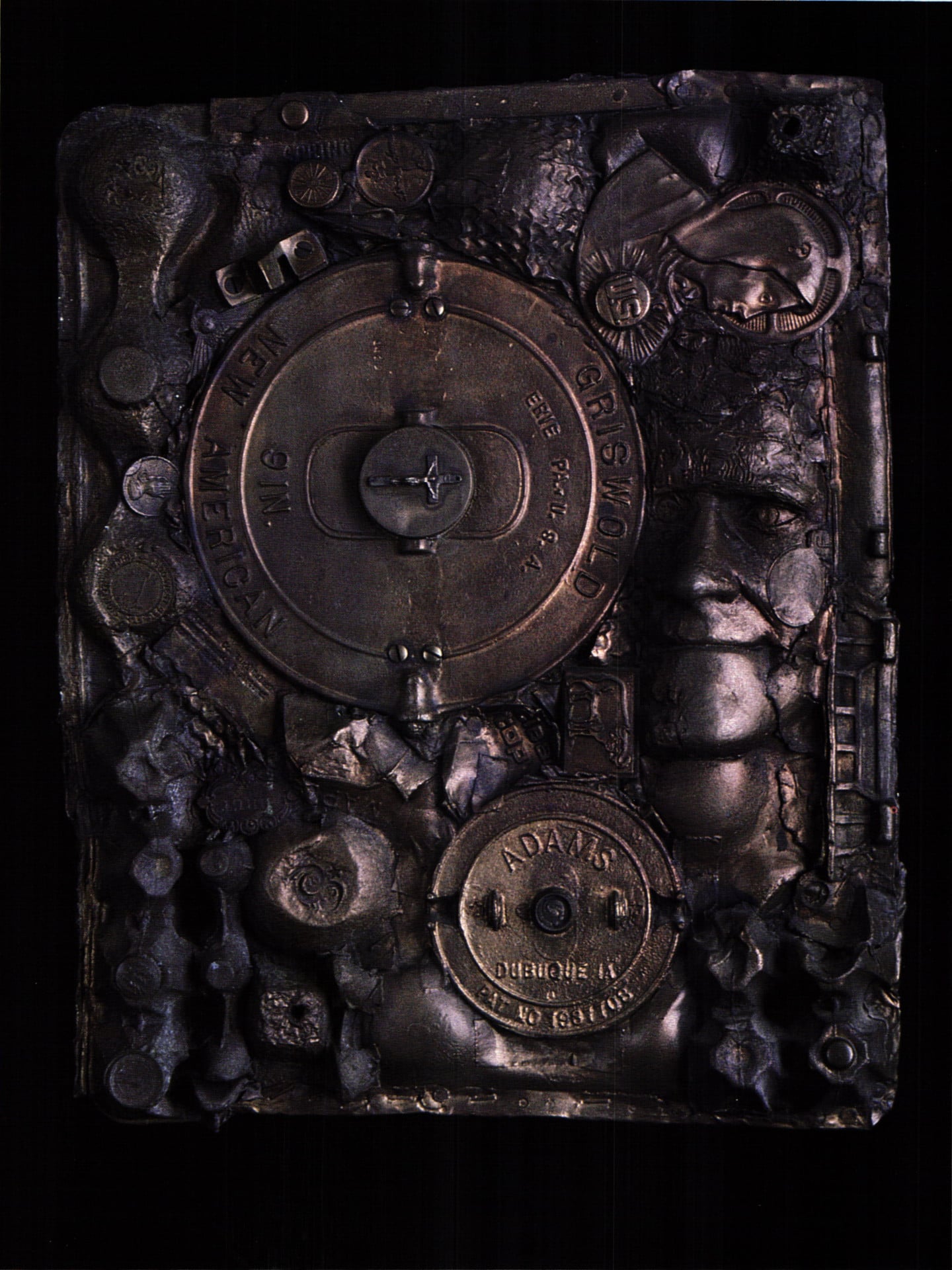

Woell's battery of ruminant heads, reliefs and fragmented torsos in cast bronze or epoxy resin appear autobiographical of the artist and his age. Emblematic of Gallo's style, they bear the pockmarks of erupting conscience, scars of anguish that stigmatize the social artist and his disenfranchised constituency. Girl with Hairnet, a youthful, wide-eyed, placid visage, is consternated by a mordantly encised skull—hieroglyphs that barely trace the outline of a maturing perception. Remnants of coins, buttons, chainlike patterning, tire tracks and other roadside attractions limn a portrait of a confused generation coming to grips with its imposed environment.

This hairnet of symbols recalls the phrenology practiced by O.S. Fowler in the 1840s, reading character traits from the idiosyncratic formations of the skull. Fowler's reputation as a strong advocate of abolition, feminism, sex therapy, birth control, vegetarianism, temperance, shorthand and indoor toilets has been ironically clouded by his mysterious forays into cranial bumps. This same has not left Woell unscathed, as he, too irony assiduously maps the plastic surface of formative emotions—the pangs of experience, the passion, fear and elation of discovery.

The series of Helmets with Nose Guard are embittered insignias for this artist as noble paladin. The armor, the brilliant guards and helmets, symbolic of the artist's priviledge, shield the battered self-portrait that lies beneath. For Woell's busts are "death masks." His vanquished busts are haunted and ambivalent, bridled by latent fears of despair, resignation and defiance that is their fate. Pilot Head glares out, one lens of his goggles missing, with an anxiety akin to that of the Vietnam soldier who wears his dog tags on his boots, aware that both legs are unlikely to be blown off at the same time. These chiseled, wounded faces reflect Woell's despondency and melancholy, the last vestige of the artist's spirit.

The formal properties and expressive naunces of Woell's work at this time are essentially derivative of Gallo's innovations: the creamy glow, trancelike stares, languid postures and feeling of trapped self-awareness and spiritless intelligence. For Woell, however, cast epoxy resins offered the further expressive quality of etching on surface, a property that suggests the language of the metalworker. His sculptural skin allows the graphic potential of surface and plane to map expression and character independent of the modeled mass. As evidence, Noxin, a play on toxin and an anagram of Nixon, is an aggressive, invidious portrait of Richard Nixon that bears an incised ship of state on its forehead as well as star-spangled teeth grinning with arrogant patriotism.

These caricatures, heads and torsos are important evolutionary works. Out of Woell's struggle to forge personal polemics emerged a confidence in the relief—the sculptural plane of the jeweler—as the milieu of his cathartic diatribes.

Fingerprints

Whether rendered as a buckle, pin or wall piece, Woell's reliefs incorporate a graphic narrative submerged beneath the surface patina. The messages form a personal syntax of perceptually deformed constellations where each element implies a mutual complicity. The calligraphic method—a fractured vocabulary of commercial lettering, advertising images, pedestrian cartoons—offers an image surrounded by a vague aura of associations. Like fossils, these molten accretions appear to emerge and recede, grow and erode until they stabilize in congealed impressions. Like bronzed baby shoes, they immortalize mnemonic objects.

Although most of Woell's reliefs appear as satiric parodies resembling those of his Pop Art peers—compare his later Landscape Salt and, No Deposit, 1969, to Jasper John's Painted Bronze Ale Can, 1960 or Robert Arneson's No Deposit, No Return, 1961— Woell eschews their need for destructive ridicule, for exalting the commercial object to icon status. Instead, he reaches for the moral tale by recycling the commonplace and distilling an optimistic ecology, where nothing is discarded and waste is rejuvenated in symbolic reuse.

In Jesus Saves Everything, 1969, a compacted mass of crucifixes, Borax logos, coins, medals, bolts and myriad artifacts of commercial culture creates one of the most powerful images of "representable" junk, embalmed and protected as cast treasure. Woell's coded world is a readable world. His moralism requires that blatant homilies wash the surface: "Nothing is precious to man. We waste. We have little respect for anything . . . nature has been raped by our greed. Our endless orgy leaves its scar along every inch of our path . . . man is a disaster. We cannot save ourselves. So, we laugh and make fun of our plight . . . life is a joke, a bad joke."

Waste is paramount to Woell. He is a denizen of trash, a collector since childhood of things others discard. His esthetic emerges from the "junk culture" of the 60s. As described by partisan fop critic Lawrence Alloway, "Junk culture is city art. Its source is obsolescense, the throwaway materials of cities. Objects have a history, first they are brand goods, then they are possessions, accessible to a few, subjected often to intimate use and repeated use, then as waste they are scarred by use and available again. Assemblages of such material come at the spectator as bits of life, bits of environment . . . They [junk artists] attempt to transpose sociological objects of ugliness into beauty through the reformation of the esthetic experience. The formula of tangible materials, formal quality of compositions and literal meanings resonate between art and experience."

Woell's journalistic "eye" moves about the cultural landscape looking for valued trash. His relief pins are snapshots, not the completed compositions of the earlier sculptures but insouciant details of a larger travelogue that entraps the viewer in the tension of the sign, between what we know and what we think we know, what we see and what we think we see. In the tradition of all good relief jewelry, they are transformed by context, as Woell confidently uses the body, the pedestal, the detachable picture frame, the intransigent wall, to reinforce the cropping of the image as an agent of the frozen message.

Throughout his reliefs, Woell utilizes a colloquial vocabulary to engage his audience. In 3c Washington/Lincoln, 1969, the portraits of Lincoln and Washington appropriated from common currency are invalidated by the "3c deposit" extracted from the surface of a pop bottle. A text running across the top reads, backwards, "20 mule team product," complemented by the familiar Boraxo logo of "Death Valley Days." This, Woell's "coin of the realm" metaphorically mocks the most stalwart of American values, the profligacy of consumerism, the debauchery of America's Manifest Destiny, through a literal and concise juxtaposition of familiar images.

In Brand X, 1969, Woell takes on the Coke bottle, an American icon of another sort. Unlike Robert Rauschenberg's Coca-Cola Plan, 1958, and Woell's earlier Things Go Better with Coke (a crucifix with decimated Jesus figure, Coke cans and lightswitch finial), 1969, both of which combined the actual artifacts to convey unmistakable connotations, Brand X through fragmentation calls our attention to the valued status of the sign that has been sublimated by the ubiquitous commodity. Woell renders the Coke icon not for its denotative meaning but for its formal semiotic impact. In No Sex, 1969, language is more apparent as Woell relies exclusively on the text to elevate content to a three-dimensional landscape of signs and symbols. Numbers rubber stamps, rebuses, stars—the entire printer's type case—is used to provide a cool, literal argument for an emotional subject. The detached assurance of these two pins implies the goals of advertising. Whether Coke or sex, there is no qualitative difference inherent in the sign. It is the way we use these signs that provokes controversy, criticism and ultimately establishes societal value. Woell is determined to deconstruct the language of society's value system in the hope of a more enlightened conversation.

Red Badge of Courage

In the 1970s, while teaching at Wisconsin, Haystack and The Program in Artisanry, Woell fabricated a panoply of curious trinkets that echoed the playful dialogue of the earlier pop jewelry. To call them trinkets is not to trivialize their importance but to position them in relation to the relief and sculptural works. Whereas the reliefs and the sculptures carve the portrait of conscience, the "dispensible" jewelry confronts external conventions in the form of billboards. The dichotomy of a psychological detective probing inwardly and the mock conspirator dissassembling the vernacular outwardly coexists throughout Woell's career. Whereas the reliefs and busts elevated prosaic subject matter to contemplative soul searching, these little key chains, music boxes, pins and commemorative spoons insinuate a utility that in this case brings profundity down to a prosaic level.

For example, Woell's Objects to Wear production line, an apparent consumer palliative, can be construed as a group of incisive allegories. Sterling Flat—"Have you ever thought about wearing a flat tire?" Driver's Side—"Remember when that white 1953 Mercedes coupe backed into your parked car and bashed in the door . . . Fred has cast the memory for you in brass so you can wear it and tell people that each time they ask: What's that?" America Dines Out—"If you eat out often at quick food establishments where the sweet smell of success is 'grease,' wear America Dines Out. It may cure you of the habit . ."

Consumerism, the plunder of morality and conscience are recast in jewelry as caustic quips that "zap" authority and convention. The motif of the auto fragment, violated icon of wealthy America, the crushed fenders, the "auto bones" dangle from Woell's dime-store key chains. These pocketed fetishes secure the symbolic spoils of our insatiable acquisitiveness: the car keys, house keys, office keys . . .

This posture of humorous, commercial parody did not begin with the trinkets of the 70s nor with the earlier reliefs. They generate from Woell's first notable body of work, the 60s jewelry that has long established his reputation as jewelry's punster. But, in retrospect, these pop compositions appear time bound not only by the evolving history of modern jewelry but also by Woell's own artistic development.

The miniature Heinz pickles and sundry bottle caps that have endeared him to a loyal following broke the restraints of Scandinavian minimalism and holdover 19th-century baroque ornamentation that shackled the growth of idiosyncratic exploration. The figurative imagery, the found objects, the disregard for material heritage, the raw fabrication, the colloquial content, the effortless compositions linger as contemporaneous criticism, a cleansing self-criticism that has had a profound effect upon jewelry esthetics. Nonetheless, in retrospect, after the trinkets, the pop jewelry seems to lose its efficacy. The youthful rebelliousness passes with time.

Consider the heralded badge Come Alive You're in the Pepsi Generation 1964, where the cameo of an exuberant, stereotypical teenager, lip-synching the Pepsi jingle while bottle caps dangle like earrings beneath, is validated by a star, symbol of legitimacy and honor. It is a placid piece, sterile in authorial expression, trite in execution; yet for Woell it betrays the inner struggle that at the time was obsessed with social relevancy and the limits imposed by jewelry's tradition. Woell takes his place in history as jewelry's first provocateur for these daring ventures into iconoclasm, yet in his entire artistic work their relevance should remain as a temporary formative influence on the road to the reliefs and the later trinkets.

The commemorative spoons that culminate the trinket variations reach for symbols that are more resolute in personal responsibility than the Pop jewelry of the 60s. They are in the best tradition of the miniature, the legitimate contribution of the craftsman/artist, where intricacy of detail combined with the diminutive scale of narrative and symbolism forces the spectator into intimate dialogue with content.

Woell's choice of debased jewelry—spoons, key chains, music boxes—mimics trophies of consumerism with puckish sarcasm, just as his "nominal" pins ape medals and badges, awards of another kind. These trinkets mark an exploration of the confluence of sculpture's imagery with jewelry's scale and tactility. In the spoons, particularly, the bowl not only serves as a base for the formal composition but also as a reflective surface that mirrors the user, implying the necessity of function for recognition. This assemblage of totemic symbolism infers unniversal dependency on imagery to validate choices. Like a primitive talisman or idol that is meant to be held and felt in daily use, they elicit the control of American "folk" mythology: Be Prepared, Requiem to a Luke Warm Lover, The Boy Scout Gets Old.

Footprints

In 1984, Woell mounted his most recent show, marking the departure of the Program in Artisanry, where he teaches, from Boston University, to Swain School of Design. More mellow, more reflective, the assemblages [see cover] that Woell offered were that of a retiring sage rather than a strident activist. This is not a retirement from productivity, as the work exhibits the full range of contemporary imagery and exploratory compositions, but a retirement from social polemic.

In 20 years, Woell has produced an notable body of work that through commitment has overcome the lack of exposure and critical support. Now, he has retreated into the friendly confines of his collected memories. These tranquil, pleasing assemblages, in the classic style of Kurt Schwitters, retain the longstanding fascination with found objects but without the benefit of metal's transmogrifying power. The prosaic icons stand full-scale, naked in patina and commonplace in resonance.

One of Woell's infamous slide lectures, which present his themes in an updated audio/visual format, is called "Connections." In it melodic narrative traces the concepts of fasteners, from barbed wire fences, to jewelry clasps to the people and places that have tied together Woell's personal narrative, ending with bucolic images of Maine where he lives. The serenity of the landscape signaled the repose that Woell has found in his own connections, the hamlet of thoughts and beliefs, which is where it all begins and ends. Woell, like Gallo, has found empathy with our culture. He accepts its inevitability without justification. He has internalized the struggle for reformation and has found the center. He has found the fulcrum of conscience at a time of debased ideology and commitment, for politics needs to migrate into autonomous art and nowhere more so than where it seems politically dead.

Notes

- The Eccentric, Birmington, MI, November 5, 1970, p. 15B.

- William C. Seitz, The Art of Assemblage, New York: Museum of Modern Art, 1961, p. 73.

- Text from Woell's "Objects to Wear" mail-order brochure.

Michael Dunas writes on art, craft and design.

You assume all responsibility and risk for the use of the safety resources available on or through this web page. The International Gem Society LLC does not assume any liability for the materials, information and opinions provided on, or available through, this web page. No advice or information provided by this website shall create any warranty. Reliance on such advice, information or the content of this web page is solely at your own risk, including without limitation any safety guidelines, resources or precautions, or any other information related to safety that may be available on or through this web page. The International Gem Society LLC disclaims any liability for injury, death or damages resulting from the use thereof.

The All-In-One Jewelry Making Solution At Your Fingertips

When you join the Ganoksin community, you get the tools you need to take your work to the next level.

Trusted Jewelry Making Information & Techniques

Sign up to receive the latest articles, techniques, and inspirations with our free newsletter.