The Jewelry of Vincent Ferrini

7 Minute Read

On the second floor of a historic wooden building in an elegant shopping area of affluent Concord, Massachusetts, is found the studio/gallery of Goldsmiths 3. This environment reflects the mature stage in the logical progression that has melded a working-class ethic with the independent spirit of the post-World War II studio jeweler.

The founding partner of Goldsmiths 3 who embodies this spirit is Vincent Ferrini. Born in 1933 in Brockton, Massachusetts to a baker's family, Ferrini's pragmatic imperative came naturally. As a child, he spent solitary hours disciplining himself in the production of accurate model airplanes-not crass plastic toys, but painstakingly executed wood and stretched-tissue objects. Quiet and withdrawn, he spent countless hours in the forest near his home, observing the natural cycles of predation, death and regeneration. The innocent beauty of nature imprinted permanently on his information base and developed in him a reverence for life and its intangible structures as well as a permanent skepticism for technology. He was also deeply influenced by the baroque opulence of his grandmother's house, especially a lavishly decorated demitasse set. These informal, esthetic traditions were easily harmonized with his deep love for the forest, forming a predilection for rich surfaces and well-integrated forms.

In 1955, Ferrini graduated from the School of the Museum of Fine Arts in Boston with a BFA The year 1955 was not auspicious to begin a career in the crafts. There were no established markets. Even the now ubiquitous crafts fairs did not begin to take shape until the mid 60s, and while the League of New Hampshire Craftsmen offered a systematic statewide sales network, it was only accessible to New Hampshire residents. So, in deference to the necessities of becoming a responsible citizen and earning a living, Ferrini enrolled at Tufts University and in 1956 received a BS in teacher education. He returned to Brockton and taught art in the public schools until 1963 when he became disillusioned with the mindless bureaucracy. In a courageous decision, he resigned his tenured position and became a student again.

He chose to study with Hans Christensen, whom he admired enormously, at RIT's School for American Craftsmen. Under Christensen's guidance he found it necessary to suppress his neobaroque tendencies and adopt a slick Danish veneer. Nevertheless, Ferrini was able to learn seaming and alternative raising methods, which broadened his technical base. Under Christensen he was also forced to examine his views about the nature of design and its relationship to personal observation and intuition. The prevailing system was more analytical and rational, stressing the elimination of extraneous detail and asserting the simplicity and the wisdom of the Danish style. The fact that these concepts were in conflict with his earlier training as well as his own convictions contributed greatly to the development of his mature style. Moreover, he now feels that although many avenues are open to him because of his technical abilities he will not explore them because of his working-class ethic. For example, he is unwilling to develop purely decorative objects that are unsalable or nonutilitarian.

By 1967, after a period of neoclassical experimentation, Ferrini found his baroque tendencies reasserting themselves. The delight he takes in rich textural surfaces, open lines and opulent materials is clearly evidenced by jewelry produced during the early 70s. Therefore, it is a complete surprise to witness Ferrini's stunning return to neoclassicism in his major work of 1975-76.

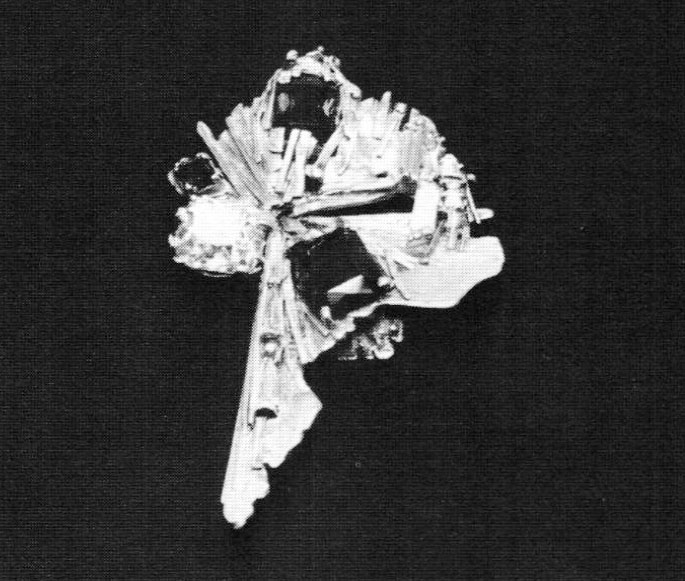

To understand this reversal, we must consider Ferrini's itinerary prior to and during those years. He spent 1974 in England, traveling throughout the British Isles. He was particularly drawn to Celtic design, finding in the artifacts of those ancient peoples kindred spirits. They, too, maintained a reverential disposition toward the power and mystery of nature so compelling to Ferrini as a child, and their use of dynamic geometry fascinated him. Incorporation of this spirit was evident in 1977 when he created a brooch entitled After the Celts, composed of silver, copperstone, agate and onyx, which expressed in simplicity and elegance those formal relationships that had only been hinted at in earlier extravagant textures.

In 1981, Ferrini was visiting artist for the Sydney College of Art in Australia. He traveled extensively and was overwhelmed by the strange, exquisite diversity of the flora and fauna. In 1982, he commenced a year-long series of jewelry reflecting the serenity, beauty and hostility of the multiplicity of life forms residing in an acrimonious cycle on the Great Barrier Reef. This body of work allowed him, for the first time, to deal directly with the wonder he felt as a child in the forest. As a mature artist, he possessed the resources necessary to bring many natural relationships, which had always been alluded to in his work, to the surface where they could be dealt with directly and powerfully. The full impact of this series cannot yet be assessed.

Ferrini's life work was well documented in a 30-year retrospective at the Brockton Art Museum in 1983. On this occasion, he wrote in the catalog of the show an insightful passage on the evolution of his work:

"When I look at the work, I am fascinated by my long-term involvement with certain identifiable lines, shapes and forms which appear in the very early years of the hands of the young artist, trying something out, sometimes tentatively, and then gaining the strength of conviction and experience in later repetitions. Sometimes a line or form disappears for years at a time and then reappears in a slightly different guise, juxtaposition, or scale. . . . Being in a position to review my work over a 30-year span affords me the opportunity to recognize its long-term, short-term and cyclical design characteristics. The technical quality of any one period varies somewhat in reaction to the character of the preceding period, but the design quality and character change more apparently. For example, the work from 1965 to 75 was extremely free both technically and in design, in sharp contrast to the work of the preceding decade. Along with many other artists, the freedom in my work of the 70s was the result of a generally freer, more experimental political, social and moral wave which swept the Western world at the time. Although I was never in the forefront of any such revolutionary movements by virtue of age (just a bit too old) and temperament (never a joiner), I was certainly affected by them, I feel, to my benefit.

Currently, the more conservative mood of the late 70s and early 80s is affecting my work, serving to reestablish my long-term interest in cleaner more classical forms."*

Throughout his career, Ferrini has maintained a large and successful business, producing unique jewelry on commission. Most of the work in his retrospective had to be borrowed from clients. His business had, however, remained secondary to his teaching. He was an associate professor at Boston University, where he has taught in the department of art education from 1964 to 1984. In consistently wishing to demonstrate the feasibility of alternatives to academic life, he, with partners John Reynolds and Bob Fairbanks, launched Goldsmiths 3 in 1983. The company has developed a rotating schedule to encourage each artist to exhibit independently and continue personal esthetic development. While the exigency of a young business precludes the utilization of optimum time blocks for experimentation, the venture is organized to allow each participant additional personal time as the business grows.

Another aspect of this operation that ensures continued personal development is the reliance on custom work. All of the work exhibited in the showroom is unique, and while it is for sale, its primary purpose is to acquaint potential clients with the level of quality and individual styles of the three. This atmosphere allows clients to establish individual relationships with one or all of the goldsmiths. Holloware is on display, but it is jewelry that supports the business. Ferrini attributes the difficulty in selling holloware to two major social conditions. First, there has been a great reduction in the purchase of ecclesiastical ware as churches have in general become more socially active and less ritualistic. In addition, the changes in patterns of family life as well as the substantial increase in theft have reduced the desirability of expensive tea and coffee services. There is also a tendency among those few people willing to invest in silver holloware to be focused esthetically on traditional reproductions rather then post-modern work. At present, they are selling only their own work. They hope, as the business develops, to be able to represent a limited number of other metalworkers.

In developing Goldsmiths 3, Ferrini has demonstrated that with proper research, site selection, and compatible coworkers, one can successfully produce high-quality jewelry and maintain a business without relying on teaching or the development of a production line to make ends meet.

*Ferrini, a Retrospective catalog, Brockton Art Museum/Fuller Memorial, Oak Street, Brockton, MA 20401, pp. 9—10.

Curtis K. Lafollette specializes in holloware and mathematically based sculpture. He is a professor of art at Rhode Island College in Providence.

You assume all responsibility and risk for the use of the safety resources available on or through this web page. The International Gem Society LLC does not assume any liability for the materials, information and opinions provided on, or available through, this web page. No advice or information provided by this website shall create any warranty. Reliance on such advice, information or the content of this web page is solely at your own risk, including without limitation any safety guidelines, resources or precautions, or any other information related to safety that may be available on or through this web page. The International Gem Society LLC disclaims any liability for injury, death or damages resulting from the use thereof.

The All-In-One Jewelry Making Solution At Your Fingertips

When you join the Ganoksin community, you get the tools you need to take your work to the next level.

Trusted Jewelry Making Information & Techniques

Sign up to receive the latest articles, techniques, and inspirations with our free newsletter.