The Jewelry of Glenda Arentzen

12 Minute Read

At mid-career, goldsmith Glenda Arentzen still produces jewelry with the freshness that has been her hallmark for a quarter of a century. It permeates whatever she makes, appearing not only in lively, asymmetrical profiles, but also in details: the crisp edges of a 24k gold earring; the apparently spontaneous shape of a brooch; the loose but precise fit of a textured scrap of gold to its structural support. Arentzen's light but authoritative touch never emphasizes metal as a precious commodity, but rather as a means to illuminate ideas.

In addition to the characteristics above, the work now is tempered with a new ingredient, the artist's seasoned reflections on human life and nature. During the past decade, this enriching content has been mined primarily from Arentzen's experience of living and working in rural New Hampshire.

On many counts, Arentzen typifies the generation of artists in craft mediums, who came of age in the early 1960s. In 1962, the year she received a bachelor's degree in art from Skidmore College, representation in "Young Americans" at the Museum of Contemporary Crafts (now the American Craft Museum) launched her exhibition career; a two-year stint as an assistant in Adda Husted-Andersen's New York studio was followed by a Fulbright year in Denmark; after earning a master's degree from Teacher's College of Columbia University, she taught part-time at the Fashion Institute of Technology and other schools to supplement her income from commissions and other sales of work.

Each step forward was a pioneering venture along paths that, at the time, were only sketchily defined. As the field's horizons have widened, her development of knowledge and skills has kept pace with opportunities, among which is a gift for Queen Elizabeth to present at Ascot, and awards that include three from Diamonds International. Her extensive research into patination and the work that resulted from it introduced a new vocabulary of color in silver and gold.

Although some time ago Arentzen reached the professional level where jewelry sales earn her a living, she has managed to retain her pioneering spirit. And, although her career might be read as a blueprint for success as a metalsmith, the zest for life that overflows into her work is a singular, nontransferable trait. She once described object-making as the "visual record of my adventures."

One morning last spring at the Aaron Faber Gallery, Arentzen was interviewed amidst an installation of 75 new works amassed for a solo show. Just emerging from "the frenzy of the final pieces," she seemed still energized by the process of creation.

As she shifted her attention from one object to another, her conversation sparkled with images that have influenced her forms: the patterning of rocks on a hillside; the cracks in a macadam road with something oozing out from beneath; a wet leaf hitting her face in the fall; the downward thrust of a waterfall, echoed in the metal "rain" falling from an earring. She conveyed the impression of an alchemist who had transformed the New England landscape into gold. In particular, a large percentage of the pieces had been inspired by the flow of water. "I seem to have become attuned to my surroundings in motion," she observed. Ironically, it was not beside a brook, but, rather, on the platform of a New York City subway station that she became poignantly aware of this attunement.

"I remember the feeling of revelation when, a couple of years ago, a woman, an underground street performer with a microphone, was singing a rap song with a cadence like a flow. It went on for many verses; each had something to do with a civilization, starting with Egypt and going all through history. The chorus was about a river, and had a feminist viewpoint: woman is the river. There was a kind of feeling that connected with what I see in rivers - for instance, when I'm in a plane flying low enough to watch how they flow."

River is the title of the necklace that served as the show's centerpiece. Its fat, textured curves of gold narrow and widen as they separate and join, compelling the eye to trace a circular course. Although it has a raw simplicity, its gentle rise in the center as well as its construction in segments suggest a fluidity intended to accommodate the body. "Some people have the misconception that something can be either art or wearable, that it's impossible to make art jewelry that is also comfortable. With River, l wanted to make an art statement, but also wanted it to rest on the shoulders properly, to meet its obligations in terms of concept."

This new work is mostly organic images based on natural forms that hold emotion for Arenzen. Inspired by both micro and macro views of landscape, the pieces are not objective translations, but rather, abstractions reflecting the attempt to get inside ideas, to capture essences that would offer viewers, and particularly those who wear the jewelry, access to fantasy. "I wanted to make comforting, provoking, stimulating, 'places to be' - in many ways they are retreats," she said. "When pieces really work, you feel a passion in them that seems to be getting at some elemental areas of life." Arentzen's notion of her work as "places to be" was expressed in an article in Craft Horizons in 1976. Since then, however, her personal frame of reference for "place" has radically changed, and this has affected her ideas.

Although her business is centered in New York, and she still has a New York apartment, 10 years ago she headed For New Hampshire to enter a new phase of life. The object: to merge her life with that of Rick Harkness, a glassblower she had met at the Haystack School when she was learning to blow glass herself. Harkness's country house was equipped with a "wood stove, dirt cellar, cows and step-children." The jolt that accompanied the move was more than that from the simplicity of living alone to the complexity of a household. It also meant disconnecting, for long periods, from the stimulation of urban life and interaction with peers and customers who appreciated the expressive character of her work.

Although New Hampshire is a craft-conscious state, dotted with guild-sponsored shops, Arentzen realized that her artistic orientation veered from the regional norm. "There, I noticed that the idea of body ornament is little pieces of metal on people's ears and hands. Even with people who have money and travel a lot, jewelry isn't ostentatious. It seems that in urban areas the need is stronger for statements of personal expression. In New Hampshire, it's impolite to stand out."

The lack of response to her work there has been disconcerting. "When I wore some of these new pieces, they provoked no comments. There is always an occasional comment in New York. I'm not looking for a positive, or even a constructive reaction, but when people comment by looking, they complete a piece with their eyes.

"Feedback from colleagues and galleries helps shape your work. I had to reorganize the way I touch base. Now, I regularly spend a 'library night' looking at art magazines. I've also been making the effort to read books on philosophy of design."

Early influences that have continued to sustain her are a graduate course with Rudolf Arnheim at Columbia and painting as well as jewelry courses with Earl Pardon at Skidmore. "Earl Pardon had certain principles for guiding you through a critique of what you were doing - not calling things 'good' or 'bad,' but evaluating your work in terms of connecting forms to concepts. Arnheim went from one element of design to another and explained why things happen in terms of his psychological and visual research. That gave me a solid grounding in Gestalt psychology, in the way things work."

Indeed, this seems to be reflected in Arentzen's ability to distill visual ideas in configurations that seem uncontrived but irreducible. For example, in a necklace called, Stepping Stones, in which angled units just meet at irregular intervals, one immediately feels a tenuous balance, a precarious dance from one section to another.

Although two years ago Arentzen's 25-year retrospective at Faber was critically acclaimed, the spring show challenged her to reach beyond past successes. "This was different from other shows," she said. "When we were setting the date, the people at the gallery encouraged me. They said, 'make the stuff that speaks to your heart, and we'll sell it.'"

While welcoming the freedom to create a collection without the commercial constraint of satisfying budgets or tastes of potential customers, Arentzen also recognized that some determinants in the normal process of design had been eliminated. "Ordinarily, when I'm organizing a show for a gallery or a big fair, I take a concept and expand it by trying to make accessories for certain prices and occasions, for shorter or taller people. Although I was still concerned with wearability, this work was not made for the market but in the service of an idea."

Permission to follow her intuition led her to concentrate on a few major works but to forego "drop-dead exhibition pieces" in favor of "things that were smaller and quieter, that made a statement, pleasant or not. Stones were used sparingly and usually seemed to emerge from the colors of the metal around them, rather than to assert an independent presence. The gallery's directive also allowed the simplicity that best exploits the use of 24k gold, which in combination with 14k gold and sometimes silver is contained in a fifth of the pieces. Most often, it occurs in unpretentious, almost casual forms that subtly glow in relation to the metals around it. "It has a warmth that leads the eye in, with a lot of impact in a wonderful way," Arentzen observed.

Although she seemed a bit concerned that, technically, the jewelry world would find nothing new in the show, it does reflect her efforts to deal with some problematic aspects of this softest, purest gold. "There's no place to hide the rough spots; fittings have to be perfect because you can't file away the excess." To offset its softness, she Found she could back it with a thin layer of a different gold.

As a spinoff from the show, she intends to continue working with the contrast between 24k gold and other metals. In particular, she wants to pursue a series of pins she refers to as "secrets." Suggestive of samples from the layers of a wooded terrain, these are made with fragmentlike shapes of 24k gold, loosely set in frames and repousséd in a way that both hides and reveals stones and other elements just beneath the surface. "Although we live in an earring culture, pins are the things that lend themselves to themes," Arentzen said. "They are more easily perceived as fine art, and most readily related to the framed form."

She also expressed a special satisfaction with several earrings and pins in which wire gridlike structures held what appeared to be casually formed "shards" of 24k gold. Lightly held in place, they were reminiscent of leaves blown into bramble bushes. "They're like impressions of the flotsam and jetsam of life," she observed. "The geometric wires could be seen as a manmade way of trying to pull something organic together."

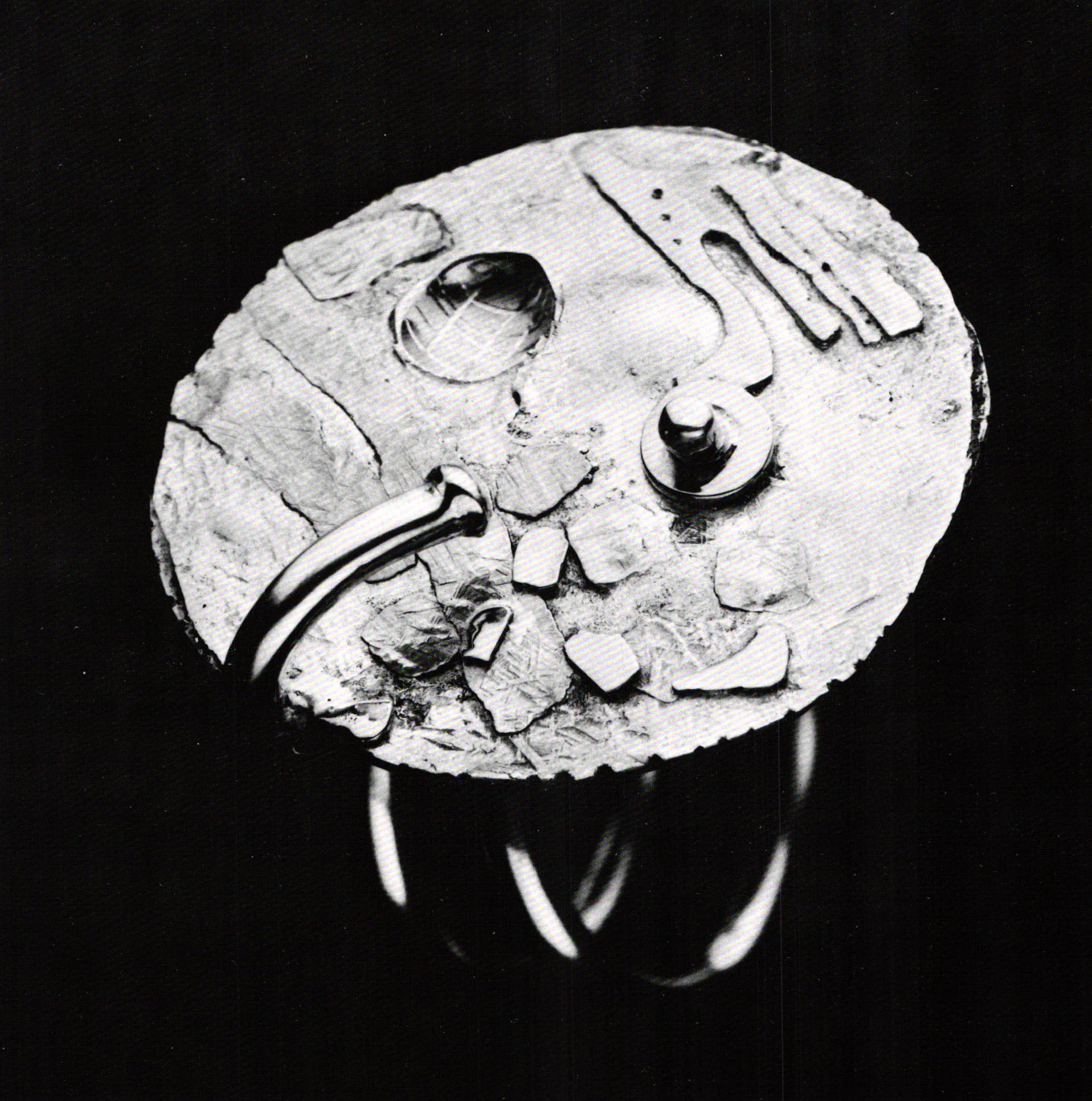

In striving for elemental qualities, Arentzen has become aware of certain forms with universal appeal. "All kinds of people have a positive emotional reaction to a wide ring that encloses the finger," she noted. Even when her rings are as dramatic as Landscape, a disc that rests on three fingers like a lily pad, the fit of the unseen band is a critical component. However, she also made a choker designed to feel constricting - "like you're jumping out of your skin" - that seems to contradict her usual regard for comfort. This piece emerged from her experience of feeling the press of life's demands from many different directions.

Between the cases of jewelry on the gallery walls hung several finger-painted works on paper, executed with sweeps of black paint and gold-leaf, veiled with tracing paper. "A lot of those are sketches that later may turn out in wax," she said, alluding to the paintings as "background noise." The brisk strokes and swirls suggested warmup exercises for the linear patterns, the ridges and incisions carved in the wax Arentzen prepares for casting. "Drawing is where the idea becomes tangible for the first time. It may be just a reference, but it tells a lot about the way you work."

For Arentzen, casting is a critical tool for making textured parts, which she later assembles, interspersing them with smooth components. She values the handmade quality of the wax units that sometimes carry fingerprints or drops of melted wax into the metal. Her reliance on casters in New York is a major drawback in living far away from the city. The easy procedure of delivering wax locally and picking up the metal on the same day has been replaced with a mail-order system that takes two weeks to complete. The time gap, however, has not vet discouraged Arentzen from using this approach to working out her ideas.

Noticeably absent from the recent show were the elegant, sleekly sophisticated, geometric-patterned forms that Arentzen had perfected, using colors achieved through patination in the married-metals technique. Two years ago, an article in Ornament discussed this work, along with Arentzen's conviction that their complex, pieced-fabrication served as a refreshing complement to the textured work. Arentzen's present distance from casting facilities suggests that this might have been the logical direction to follow, but her ideas have moved away from it. "I've nearly stopped doing it, not because I feel negative about it, but because I'm finished with it. I resisted the temptation to do it; the fat, graphic quality didn't seem as important as the landscape ideas."

Perhaps a key to the vitality of Arentzen's work is that, in addition to continually scrutinizing and reflecting on the visual world, she also keeps her inner sense of texture and pattern alive by a regular routine of both tap and ice dancing. With the exhibition's opening behind her, she was looking forward to her 50th birthday, an occasion for a carwheel. Predictably, the embodied memory of that arc in space will someday find expression in gold.

Notes

- Smith, Dido, "Glenda Arentzen's Magic Metal," Craft Horizons, February 1976.

- Blauer, Ettagale, "Glenda Arentzen: Contemporary Goldsmith," Ornament, 12 (3), 1989.

Patricia Malarcher is a fiber artist and craft critic.

You assume all responsibility and risk for the use of the safety resources available on or through this web page. The International Gem Society LLC does not assume any liability for the materials, information and opinions provided on, or available through, this web page. No advice or information provided by this website shall create any warranty. Reliance on such advice, information or the content of this web page is solely at your own risk, including without limitation any safety guidelines, resources or precautions, or any other information related to safety that may be available on or through this web page. The International Gem Society LLC disclaims any liability for injury, death or damages resulting from the use thereof.

The All-In-One Jewelry Making Solution At Your Fingertips

When you join the Ganoksin community, you get the tools you need to take your work to the next level.

Trusted Jewelry Making Information & Techniques

Sign up to receive the latest articles, techniques, and inspirations with our free newsletter.