Fads and Fallacies: First Impressions

6 Minute Read

As trite as it might sound, we still form our opinions about people as a result of "first impressions." In fact, our fast-paced culture demands that personal images be codified within the limits of an ever-decreasing attention span.

For all but our most intimate friends and family, we depend on superficial appearance to carry the weight of character and personality. Inevitably, then, our body becomes conditioned to behave and act in front of a human audience employing the gestures and postures of a common language to signal our participation in interpersonal relationships.

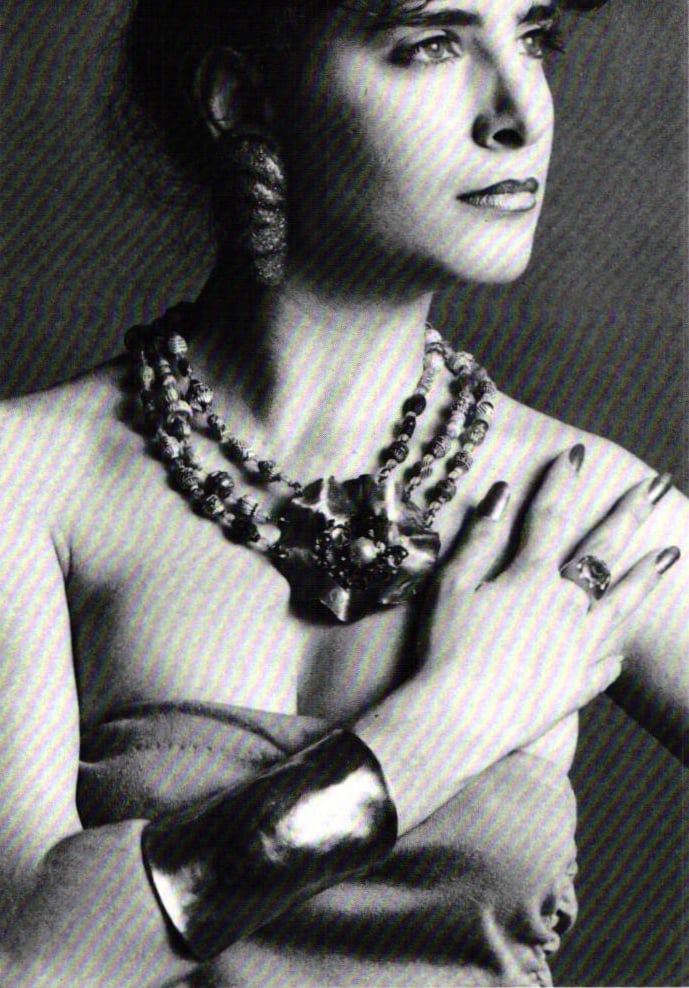

The theater metaphor is no coincidence, as actors essentially mimic human behavior in order to illuminate the complexity of commonplace actions. Conversely, the presentation of self in everyday life requires that we adopt theatrical codes in the form of dress, makeup, props, etc. that augment and often substitute for our verbal language. Seen in this light, jewelry maintains more than a tangential relationship to acting and costume as conscribed with a "staged" scenario.

Unfortunately, when we speak of costume jewelry, we generally mean jewels made of nonprecious materials, fakes, novelties, a throwaway esthetic. This pejorative definition, like so many applied to jewelry, dissolves as novelty techniques and nonprecious materials are more often successfully incorporated in what we know as fine, fashion and art jewelry. Anyway, such strict definitions, based on market applications, seem only to obfuscate the language that all jewelry shares with theater in the disguise of the masked persona.

Costume in the strict sense is a special "staged" outfit that is easily recognizable by its symbolic or historical codes. Costume idealizes the wearer in the guise of someone else. We instantly recognize an actress as Queen Victoria when she dons a gilded crown, even though we are still aware that she is playing a part. Even when an actress is not playing the part of a specific historical or fictional character, the costume might signal a separate identity. Cher, for example, utilizes her glittering, bejewelled costumes to conjure an image of "stardom," a fantasy image conveyed by the costume but conferred upon Cher because she wears it. Consequently, the enormous power of projection in celebrity photos, films and especially television has transformed fine or fashion jewelry into costume jewelry. When we see the characters in the soaps like "Dallas" and "Dynasty" wearing jewelry, our adulation for the "stars" transfers to the jewelry. It is not the jewelry we identify with but the code of the jewelry communicated by the actor's role. The jewelry is not appreciated for its intrinsic merits, but as a conduit for recognizable character traits that are assumed and fictional. In all cases, costume maintains a self-referential code that is distinct and separate from the wearer's personality.

In contrast, clothing, jewelry and other props can be used for purely dramatic effects, transforming the actor completely. While costume does not eliminate our cognizance of the actor, the actor and his role remains separate but complementary. The use of a scarf, a pocket watch, a top hat may force an actor to surface an inherent character that is part of his own personality. Fred Astaire, the debonair bon vivant is inseparable from his top hat and tails, as is Charlie Chaplin, the tramp, from his ill-fitting baggies, derby and peripatetic cane. We recognize that the tramp and the bon vivant are sublimated in the personalities of Chaplin and Astaire. The top hat, tails, derby and cane take on an added significance when employed by Chaplin and Astaire. More importantly, Astaire and Chaplin evince a specific and empathetic identity that we associate more with the traits and gestures of their personalities than those of the costume. Rather than the costume sublimating the actor, in this case, the costume is sublimated by the actor.

This difference is important when we consider the theatrical "borrowings" of fashion. Unafraid of being disguised by clothing and jewelry, the wearer can maintain the distinction between himself and his costume. However, we rarely see the appearance of dramatic jewelry. jewelry that transforms the wearer, exposing various persona that might be at odds with his quotidian image. Fashion often borrows from the staged outfit, modifying it slightly so as not to appear literal, not to threaten the personality of the wearer. For example, we might wear a motorcycle jacket to identify with James Dean or Ray Bern sunglasses to identify with Don Johnson without being conspicuously "in costume," yet we do not seek those idiosyncratic props to transform the rebel within us nor the tramp or bon vivant for that matter. We are too afraid of being vulnerable, of removing the facade that the costume offers as a defense against dramatic impulses. The rare occasions when dramatic jewelry is sanctioned are the "ball" or "club party" and other contrived staged events where theater is required and where the catharsis of acting is encouraged. These have become the havens for entertaining "who we would like to be" rather than agonizing over "who we really are."

This concern for our real personality as understood within a social code is the prerogative of fashion. Its tradition derives from the public arena rather than the proscenium stage. Fashion's goal is to find a place for us in the social mise-en-scene through clothes and jewelry, either comfortably blending in or distinguishing ourselves, depending upon our inclinations. Historically, fashion signaled the nobility of social class (i.e., the use of luxury materials and precious jewels). As fashion became democratized, as the public arena became open to all social classes, new codes were needed. No longer was the display of status confined to the privileged; anyone could participate in the ritual by simulating an acceptable image. Power shifted to tastemakers, style innovators and new social icons like movie stars. Power shifted away from wealth and status and toward the codified image of celebrity. The dynamics of the code remains the same, as it is arbitrary and fictional, only seeking to assimilate a larger public into the structure of social interaction. Instead of looking to nobility as our measure, we look to the covers of the fashion press, the trendsetting designers, the mysterious arbiters of style who speak in whispers of what's in and what's not. Even the ostentatious finery, bombastic colors and outrageous forms that we identify as punk, subversive, cheap "street jewelry" that is far removed from notions of elegance and class is nothing more than another code recently legitimized.

The authority of fashion as a visual convention is gladly accepted by everyone, yet we go to great pains in distinguishing it from theatrical costume. We believe that the street is the arena of reality not illusion. In looking at fashion, the pleasure of recognition is more satisfying than the pleasure of perceiving dramatic coherence or staged appropriation. In liberating jewelry from convention, maybe we should examine more closely its efficacy as costume and its catalytic role in body drama.

From the Author: I want to credit the pioneering work of Anne Hollander for inspiring and informing this column.

A. Stiletto works in and around New York and writes a regular column on fashion.

You assume all responsibility and risk for the use of the safety resources available on or through this web page. The International Gem Society LLC does not assume any liability for the materials, information and opinions provided on, or available through, this web page. No advice or information provided by this website shall create any warranty. Reliance on such advice, information or the content of this web page is solely at your own risk, including without limitation any safety guidelines, resources or precautions, or any other information related to safety that may be available on or through this web page. The International Gem Society LLC disclaims any liability for injury, death or damages resulting from the use thereof.

The All-In-One Jewelry Making Solution At Your Fingertips

When you join the Ganoksin community, you get the tools you need to take your work to the next level.

Trusted Jewelry Making Information & Techniques

Sign up to receive the latest articles, techniques, and inspirations with our free newsletter.