The Copperwork of Santa Clara Del Cobre

11 Minute Read

Dusty cobblestone streets traversed by oxen and donkeys pulling hay carts, anvils ringing, woodsmoke, chickens pecking next to the wooden bellows and a new Volkswagen Jetta parked in the yard of an outdoor shop — these images reflect the dichotomy of the guild community of coppersmiths, master craftsmen, who work today in the same manner as their fathers and grandfathers in Santa Clara del Cobre, in the State of Michoacán, Mexico. This is the antithesis of the glitz of Taxco's silver.

Located in the forest of the lake region of Michoacán. Santa Clara is 16 kilometers from Patzcuaro and 78 kilometers from Morelia, the state capital. The rural town's economic activities are all closely related to the hand-production of copper objects by its more than 2000 craftsmen who pound their wares in the yards behind the stucco walls. The shops are generally humble lean-to extensions of the homes and each family member adult or child, has his or her responsibilities in the shop. Blacksmiths produce the tools for the coppersmiths (though many produce their own), others produce the high-quality charcoal needed for copper smelting. Local agriculture nourishes Santa Clara, and the wood cleared from the fields is used in the charcoal production and as fuel for the bellows. Even the regions traditional pear candies are of course cooked in large copper kettles.

Copperwork was most likely introduced to Middle America from Peru by sea and first appeared in the late classic or even post classic period. During pre-hispanic times (prior to 1492 A.D.), the indigenous inhabitants of the Michoacán region, the purépecha, worked copper to produce body adornment, such as beaded necklace, pectorals and ceremonial objects in the form of anthropomorphic figurines and bells. Utilitarian needs were met in the production of wire, hachets, fishing hooks and so forth. In the colonial period, production of these objects was abandoned by, order of the powerful Franciscan friar. Vasco de Quiroga, and replaced with the production of a "traditional two-handled Spanish casserole." This "vessel of Uncle Vasco," as it was known, still relied on pre-hispanic smelting and some raising techniques and permitted continuation of these processes over the next 400 years, but also introduced European processes to the purépechas. Throughout the 300 years of colonial rule, until the 19th century, and even into this century, production of the now traditional casserole form, industrial vessels (fondo) produced for cooking the cane sap in the sugar mills and for distilling spirits, and the utilitarian holloware, like washbowls and pitchers, remained virtually unchanged in process or design.

In 1946 the municipally sponsored "Patriotic Committee of Santa Clara" initiated the first of three competitions to stimulate the town's copper industry which by this time was threatened with extinction. In 1949 a new organization "Friends of the Coppersmith" was formed and continued to sponsor annual contests until 1957. The contests succeeded in providing an impetus for technical development. individual creativity and diversification of forms. Even so, the contemporary coppersmiths of Santa Clara have retained many traditional elements of form and especially of process, to the point of using the nomenclature of their purépecha ancestors yet today. There are three basic types of copper hollow form production in Santa Clara, including cooking kettles, traditional vessel/pot forms and creative vessel/pot forms.

Since the copper mines in this region ceased functioning last century, the craftsmen utilize scraps and recycled copper for their prime materials. A significant portion of their metal comes through an agreement with the Federal Electrical Commission for scrap cable wire. While industrially produced pure copper costs about 2,250 pesos per kilo, the price for the scrap copper ranges from 200 to 400 pesos per kilo. A typical vessel will cost a craftsman about 800 pesos for materials, at the current exchange rates, less than two dollars. The utilization of scrap metal keeps the vessels competitively priced and assures the economic survival of the community.

Scrap copper is inexpensive, however it requires smelting and this is performed in the individual home shops following the same technique that the pre-hispanic purépechas employed. (In that time copper was smelted as it was extracted from the earth.) Therefore, rather than using a crucible, a depression is made in the ground, (cendrada), covered with oak ashes (petacua*) and surrounded with "fire rocks" (yápicua*). In one shop, the coppersmith stated that 8 to 16 kilos of copper are smelted in this manner at a given time. The design of the typical double-tubed bellows for reducing the charcoal (turiri*) smelting fire and wood (shari*) annealing fire is also linked to the pre-hispanic past, and is derived from the use of reeds as blowers.

Basalt stones are used as anvils on which the hot hemispherical ingots are often cut into smaller billets, using a tongheld wedge and sledge hammer. Even though there are two trip-hammers now in the town, many of the smiths handstretch the copper hot with 14-16 pound sledge hammers. The copper is worked hot throughout the stretching and raising of the vessel and initially requires at least two men, one to hold the hot metal and the other(s) to strike the hammer blows, to accomplish each course of raising. As many as 10 men may hammer in synchronized rotation on the billet. Stakes and hammers, though functioning principally in the same manner as traditional North American metalsmiths know are specifically made and creatively adapted to suit the needs of the individual smiths. (In the case of a single smith working a form. it is interesting to note that in order to hold the hot vessel with the tongs, it is necessary to raise the vessel on a stake low enough — often mounted in the ground — that hammering is towards the body, rather than away from the smith.)

One exception to the in-shop processing of raw materials is the purchase of industrially milled copper sheer discs used in the production of trays, plates and the sinking of large cooking kettles. In making the kettles, copper discs are stacked as many as 10 at once with pitch separating the layers to prevent fusion, and these are bound together by a single, larger disc, which is folded in bezel-fashion around the edges. The entire unit is heated to cherry-red in an earthen forge and then sunk into a nearby earthen depression, again following the synchronized hammering with heavy sledges. The process is repeated until the forms are raised and then eventually separated, planished and finished with rolled edges and forged handles finally riveted to the kettle bodies.

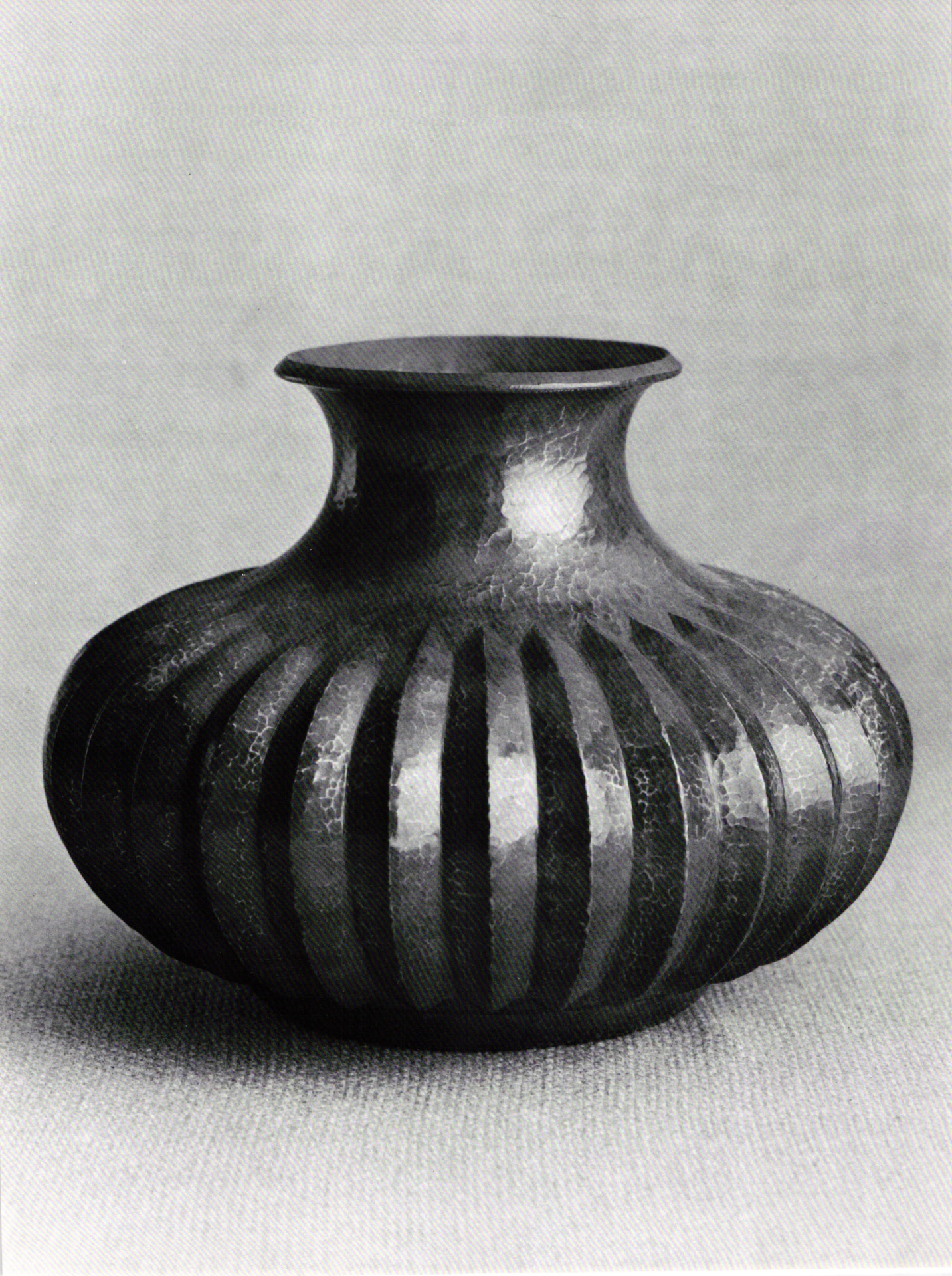

Besides symmetry, three elements of form have evolved into a common stylistic vocabulary of Santa Clara vessels. These include geometrically segmented, repousséd designs, gajeado; thick rims, bordo grueso; and working "in solid" en macizo, that is, forging certain elements such as vessel legs and handles out of the same metal mass from which the vessel is simultaneously raised. Also, the coppersmiths have distinguished themselves through their mastery of scale. There are numerous examples of stretched and raised vessels (in addition to the cooking kettles) of immense proportions — two feet high by three feet in diameter is not unusual for many of the pots available for sale throughout the town. Typically the forms are left with varying degrees of planished refinement. In addition to the traditional reflective planished copper surface, many of the smiths use a natural dark red patination that is probably obtained through the repeated heating and water cooling of the copper. Silver plating is used occasionally.

There are those few craftsmen of Santa Clara del Cobre who transcend mere technical mastery and a common stylistic vocabulary and are truly master craftsmen, men and women who are innovators within this community that maintains so much of its traditional heritage and they are recognized as such within Mexico and beyond. In a January 1986 exhibition held in the Casa de las Artesanias del Estado de Michoacán, housed within the former Convent of San Francisco in Morelia, the work of Rafaela Castro-Sanchez (who teaches at one of the two recently established schools devoted to coppersmithing in Santa Clara), Francisco Martinez-Velázquez. Jesus F. Perez-Ornelas and Abdón Punzo-Angel showed works of personal vision, sensitive and in some instances, sensual design and exquisite technical refinement in both fine silver and copper forms. Many of the vessels were functional, as in coffee pots and pitchers, and most were in the copper pot tradition but showed experimention with the definition of the traditional concepts.

The vessels of Abdón Punzo-Angel were particularly intriguing. Whether it is the work he exhibited in Morelia, or the work in the permanent collection of the Museo Nacional del Cobre in Santa Clara, or the work for sale in his family's small retail shop across the street from the museum, his sense of form, process and scale is simply fantastic. On the other side of town, his family's outdoor workshop is located within the walled yard of the small home shared with his wife and son, father, brothers Carlos and Benur, and other members of the extended family. As in most guild societies, Abdón Punzo-Angel learned his craft through apprenticeship with his father. His father began smithing as an apprentice at age 12. Abdón began learning at age four; his son is three years old and has begun playing with the hammers. Both of his brothers are also coppersmiths in the shop and their children work and play there as well.

Though only in his early 30s, Abdón is regarded as a master craftsman. All of his pieces, regardless of scale, are stretched and raised by hand; all details of form are accomplished through the use of hammers, chisels and stakes — pitch is not used within his shop for repoussé or any other forming process. Most of his work is in copper, though he has produced a limited number of vessels in fine silver, using exactly the same working procedures as for copper, i.e., the fine silver is smelted into a single large billet that is stretched and raised hot. The largest silver vessel he has raised is at least 20 inches tall by 16 inches diameter and according to Abdón, weighs several kilos.

Next to the faded stucco house, amidst the smoke, chickens, laundry and children in the workyard sirs the symbol of Abdón Punzo-Angel's recognition and success as a coppersmith — a new Volkswagen Jetta, purchased with the prize money awarded him by the president of Mexico in the national competition in Taxco, just one of the several times he has received national prizes. His vessels exhibit his respect for the vernacular forms and vocabulary that have evolved over the past 400 years in Santa Clara, but his creative sense of proportion and interest in asymmetry and abstraction of natural forms bodes well for his future as an important 20th-century metalsmith, and especially for the continuity and development of a unique community with a direct link to the past.

Santa Clara del Cobre is able to maintain its continued existence partially through a government that is sensitive to the preservation of tradition and by its organization of shops and the family work system. The children are ultimately the key to this tangible cultural link. Their participation and apprenticeships are essential for the continuation of the coppersmithing legacy.

Participants in the Society of North American Goldsmiths conference in March in San Antonio may be interested to travel to Mexico. Those who wish to travel to Santa Clara del Cobre are advised to plan hotel accommodations in the lake resort town or Morelia, Patzcuaro or other neighboring city, since Santa Clara del Cobre has no hotels. Examples of the Santa Clara coppersmiths' work are available for purchase at the Museo de Artes e Industrias de Populares del Instituto Nacional Indigenista in Mexico City and the Casa de las Artesanias del Estado de Michoacan in Morelia, as well as from the various shops in the town of Santa Clara del Cobre.

References

Cerulli, Ernesta, "Metalwork," Encyclopaedia of World Art, (London: MacGraw-Hill), 1963.

Gomez, Miguel-Angel, y Gracia, Ariel, Los Artesanos de Santa Clara del Cobre. (Museo Nacional de Culturas Populares, Gobierno del estado de Michoacan, Mexico), 1985.

Velazguez, Maria, Los Mexicanos (Mexico: Fondo de Cultura Economica), 1970.

Susan Ewing is an Associate Professor of Jewelry Design and Metalsmithing at Miami University, Oxford, Ohio.

You assume all responsibility and risk for the use of the safety resources available on or through this web page. The International Gem Society LLC does not assume any liability for the materials, information and opinions provided on, or available through, this web page. No advice or information provided by this website shall create any warranty. Reliance on such advice, information or the content of this web page is solely at your own risk, including without limitation any safety guidelines, resources or precautions, or any other information related to safety that may be available on or through this web page. The International Gem Society LLC disclaims any liability for injury, death or damages resulting from the use thereof.

The All-In-One Jewelry Making Solution At Your Fingertips

When you join the Ganoksin community, you get the tools you need to take your work to the next level.

Trusted Jewelry Making Information & Techniques

Sign up to receive the latest articles, techniques, and inspirations with our free newsletter.