The Helen Williams Drutt Collection of Modern Jewelry

23 Minute Read

The Helen Williams Drutt Collection offers a personal view of the development in fine art jewelry over the past 20 years. A refined eye that understands new developments and experimentation chose works of jewelry for their intelligence, wit, seriousness of purpose, individuality and technical excellence. Most major areas of recent development in the field are represented by these meticulously selected examples. The one area notable by its absence is that of Scandinavian design, which was so influential in studio design in the 60s.

Discursive Art The Helen Williams Drutt Collection of Modern Jewelry 1964-1984

The collection is essentially an American one, that is, the work is predominantly from U.S. artists. However, from the mid-70s to the present, the collection has developed an international flavor with work from Holland, England and Germany leading a gathering that ranges from Spain to Japan.

All the individuals and works represented in this collection are on essential part of current developments. Individual digressions include: dialogues in pictorial, iconographic, painterly, ritual or ceremonial, organic, geometric and machine concepts. There is no clearly unfolding path from one approach to another. One could follow a number of paths through the plethora of experiments.

The pictorial approach could be traced from J. Fred, WoeII through Fritz Maierhofer, Richard Mawdsley, Robin Quigley, Bruce MetcaIf, Klaus Bury, William Harper, Edward de Large, Esther Knobel and Otto Kunzli. But this is not a clearly defined path and, the diversity is extreme. Metcalf's work is comfortably pictorial, but Knobel's is not. Although Knobel's work has a pictographic quality, it draws heavily on the idea of ritual and ceremony in its use of color and form. Bury's work is pictorial in concept, but rather than human imagery it is concerned, with mathematics and the subtle and twisted perspective of a space-time continuum. The pictorial approach becomes iconographic in both Woell's and Maierhofer's work. Here are pictorial symbols that make claims for cultural universality and, in doing so, become icons.

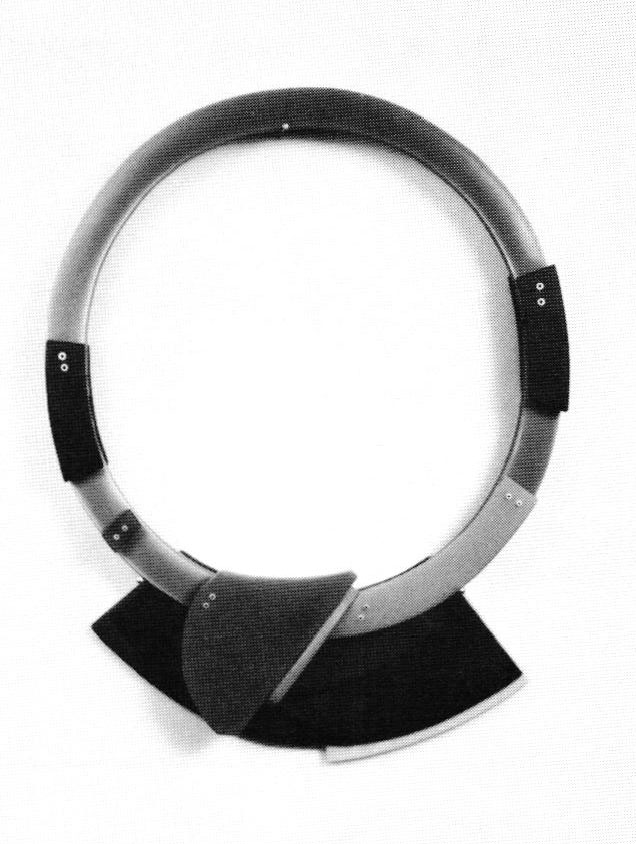

The dialogue on u machine esthetic could be traced along an equally digressive path. Working backwards from the most recent works, one might move from Paul Derrez to Maria Hees, Eric SpiIler, David Tisdale, KarI Bungerz, Emmy van Leersum, Franz van Nieuwonborg, David Watkins and Wendy Ramshaw. These sleek works are often sculptural statements and frequently geometric in intent, like Ramshaw's innovative small-scale sculptures, pieces of which are wearable jewelry. Watkins's refined combinations of acrylic and precious metals brings the idiom to a stage of modern classicism. Derrez takes the refinement beyond classicism into the space age, while simultaneously reminding one of historical precedents. Van Leersum odds color, a minimalist's color, once removed from the painterly tradition. Once again, diversity within the grouping prevails.

So, too, is the ritual or ceremonial approach a widely discursive category. Esther Knobel's collars speak of primitive forms that in turn are reminiscent of ceremony. From a different sensibility this is also true of Breon O'Casey's work. Caroline Broadhead's monofilament collar is conceptually, rather than formally, related to the, primitive and the ritualistic, which leaves its esthetic form free to be developed out of other modes. Lam de Wolfs theatrically scaled collars are also linked to the concept of ceremony. However, their painterly color and, ephemeral materials create formal ties also.

What becomes apparent is the interdependence of the paths. Individuals do not confine themselves to a single direction, and the development of artists, objects and directions intermingles. The collection is characterized by this diversity which is its strength and its value as an art historical statement.

Art since the 50s has inclined to be discursive. It has been a rambling, digressive discussion that has ranged over a wide field of subjects. It has talked about artists' psyches, commercial objects, optic nerves and external reality. It has discussed flatness, materials, negative volume and environmental space. It has talked about being ambiguous, ephemeral, literal and metaphysical. It has talked about its place in history. It has discussed its parameters. It has concerned itself with definitions. What began, earlier in this century as neatly ordered discourse for the purpose of throwing off old modes and customs has developed into what is now labelled a plurality of styles.

The Helen Drutt collection of contemporary jewelry is a microcosm of this discursive activity. Beginning with work created in 1964 and ending with work from 1984, the collection spans the most active years of a wide-ranging discussion. The collection includes 187 pieces of jewelry by 57 artists, creating an insistent dialogue on formal aspects of esthetics and an argument on such topics as abstraction, representation, content, ritual, intellect, necessity, decoration, organism, the machine, minimalism and the pursuit of beauty. This is no constructed discourse; it is an intense creative discussion that is concerned with the very essence of jewelry and develops, in rapid succession, a multitude of directions.

The discursive nature of the collection is set by its earliest works: brooches, fibulae, torques and necklaces by Albert Paley and Stanley Lechtzin. Fibulae and torques are ancient jewelry forms. A fibula is a type of brooch, specifically a clasp or buckle, used to hold a garment together. Torques are ancient forms of necklaces and bracelets made of twisted metal bands. By using the ancient terms, fibula and torque, instead of the contemporary ones, brooch and necklace, historical connection is implied. Neither Paley nor Lechtzin actually develops his esthetic out of the ancient forms that their labeling connotes. Their inspiration for design ranges from Art Nouveau to coral and crystalline growth structures and each artist develops his own unique direction. Perhaps a concentrated reworking of the antique form would have led to a more cohesive taxonomy, if that were a desired goal. However, the inspiration from several directions is layered with individual predilictions. The old labels are attached to new pieces; an instant link with the past is formed and credence is given to experimental design. This is the basis of the eclectic discussion that ranges throughout the collection.

Nature

As the 60s progressed into a back-to-the-land movement, many artists began looking to nature for design inspiration. Romantic notions idolizing the natural spirit led to a jewelry esthetic that was visceral, undulating, asymmetrical and organic. Lechtzin's electroformed crystalline structures speak of nature's growth; the hand of man seems far removed from the creation of the object. OIaf Skoogfors uses soft, undulating textures and asymmetry to relieve the regular forms and edges of his brooches. Paley's clean, flowing lines, though hard-edged, are also organic. Inspired by Art Nouveau and translated into a contemporary idiom, Paley's work represents a double transformation of style in which he redevelops a dialogue that has already been developed nearly three-quarters of a century before. His is the historical contact in the collection's early discussion.

Toward the late 60s, subtle developments in the interpretation of nature bring hints of landscape, inclusion of natural objects and representations of natural organisms. This new mode borders on the pictorial. Nature is referred to rather than absorbed and descriptive titles become part of the symbolic and referential imagery. William Harper's Pagan Baby #4: The Serpent, Pagan Baby #6: The Scarab, and Unrequited Valentine #3 develop natural themes that have vaguely psychological and philosophical overtones. The pictorial nature mode develops rapidly in its own direction soon leaving the discussion of nature far behind.

Explorations in geometric form are not absent from the earlier pieces of the Drutt collection. Geometry is the antithesis of nature and lends itself readily to a machine esthetic. Yet the overriding feelings for nature in this period turn even geometry into a softer form. This is achieved through a mixing of shapes, many of them irregular in the mathematical sense, subtle shifts of size and scale within the same work, frequent piercing of form and combinations of finishes. The result is a maximal geometry, at least in comparison to the clean, hard minimalism of today's geometric forms. It is geometry that has been humanized.

The dialogue on nature wanders along exploring various paths that are bound up with abstraction, the intellect, history, natural structures and growth. The initial inspiration from romanticized nature is only the beginning of the process. An entire body of formal concerns is also called into question.

Inspiration from nature leads early on into a consideration of the inherent qualities of things, particularly those things that are the basic materials comprising art jewelry. Gold, silver, copper, brass, precious and semiprecious stones and then plastics and glass are made to stand up and state their essential natures. Integrity of materials becomes at least a serious concern, if not an ideology, and the formal aspects of design esthetics are much manipulated as a result.

Texture

Texture is a formal device of great import and design influence. It is inextricably a part of the search for material integrity. Naturalness, pure organic textural truth, is a moot issue. The essential nature of a material has many levels of definition. Perhaps Lechtzin's electroformed work comes closer than any to manifesting untrammelled nature. But that is only where the discussion of formal issues begins. The human hand is also part of nature and traditional handworked metal techniques can be made to imitate the flowing growth of natural texture. Reticulation, chasing and carving readily lend themselves to producing organic surfaces. The question may well be: Is there a greater honesty in acknowledging the work of the human hand, tradition and history than there is in trying to remove those qualities in order to pursue some kind of purity of nature? Perhaps it suffices to say that one scarcely can remove the touch of the human hand from the kind of work in question and point out that this direction is not seriously pursued for long.

The tendency, when speaking about texture, is to think of it in terms of a nonsmooth surface. Texture may imply "tooth," but it ranges from extreme structural roughness to nearly smooth, minutely moulded surfaces. Metals are malleable and receptive to almost any kind of surface treatment. This makes the discussion of textures that are suitable to the integrity of metal particularly difficult as almost any amount of roughness or smoothness works equally well. But metal for its own, natural sake was much exploited by those who were developing an organic esthetic. Whereas in the not too distant past metal had been used as a structural device to enhance beautiful minerals, it was now glorified as inherently beautiful. Skoogfors's work develops a variety of technical themes to this point. Stones, too, are used in their more organic forms in order to emphasize natural beauty. Artists studying the forms and content of nature seem to prefer a rough or undulating quality, thereby choosing baroque or informally cut stones over the regular or more formal ones.

Plastics are well suited to smooth, subtly manipulated surfaces and thus are interesting in terms of textural exploration. However, they also raise an interesting ideological issue. Plastics are manmade substances and their integrity lies in their coming into existence at all. They are not used by artists who are seriously studying and developing a vocabulary from nature. But no discussion lasts forever, and in the rapidly changing art world of the 20th century, the urgency of the discussion on nature inevitably diminishes. Various individuals become interested in exploring new possibilities and in the late 60s plastics became more regularly used for their variety, textural and otherwise, and their own singular characteristics.

Within both the organic and the nonorganic approaches to materials and design, the seemingly limitless possibilities of textures are explored. From the rough organic intricacy of Lechtzin's electroforming to the polished undulations of Paley's inlaid stones, from the bold eclectic surfaces of Fled Woell's mixed-media constructions to the more subtle but equally mixed surfaces of Toni Goessler-Snyder's informal geometry, the discussion of texture carries on into increasingly diverse and rarified realms. Materials are sandblasted, etched, cast, carved, polished, painted and assembled to create surfaces that may or may not speak to the issue of surfaces and texture at all. Divergent ideologies are formed out of practical and technical developments. A complement of dimensions is added to the formal dialogue of design esthetics.

Color

As texture, so, too, is color a formal device of major importance and its use and development also illustrate the discursive quality of exploration in this collection of jewelry. Initially, color is subdued and minimal because of its derivation from the few metals and minerals that are used to create the jewelry. Gold is used for its own sake and its color range is not wide. Silver is used in like manner. Set stones are often closely keyed in color to the basic metal in order to enhance the natural effect of the metal. None of this is a necessary result of using these particular materials, but it develops out of the nature ideology in which truth to materials becomes linked to purity and the use of color is limited in a pure and refined manner. Nature, however, is not monochromatic and even in the early stage of this discussion there are some color contrasts being used.

Color comes into its own when the pictorial approach in jewelry has developed into a fully coherent direction. Bruce Metcalf and William Harper both paint jewelry into being, Harper by means of enamels, Metcalf by means of assembling a mixture of materials. With essentially a designer's approach, these artists use color to separate visual elements from one another in order to clarify the imagery.

Works which make use of plastics often are involved in a discussion of color both for its own sake and as an enhancement of form. The wide range of possibilities within the material itself allows for the muted softness found in David Watkins's work and the strong contrasts in Hans Appenzeller's. But the fully developed dialogue on color comes with the most recent work in the collection. And this work takes its cues from painting. Esther Knobel's necklaces are painted in the bright colors of graffiti; Lam de Wolfs colored fabric is painted from an expressionist's palette; Debra Rapoport constructs painterly assemblages; Emmy van Leersum is a minimalist with painted steel.

Color speaks to material and to intent, it enhances form and sharpens texture, it is used for its own sake and it looks to history. While there has been great variety within this dialogue, there has also been a general tendency to develop a bold hand with color. This comes with the tendency to celebrate a machine esthetic.

Formal concerns are intimately linked with the process of making, but the ideology behind the making has fluctuated rapidly over the past 20 years. That formal concerns and ideology frequently interact can be seen in the complex relationships of texture to plastics, to nature, to color. Each aspect is both formal and ideological, depending on the intent of the artist, the essence of material reality and the feeling of the times. Machine versus hand is an essential part of these issues. What begins to show in some of the most recent pieces collected by Helen Drutt is a clean, machined quality that is the antithesis of the organic approach. This is an extreme swing in sensibility, although not an all-encompassing one. At the same time, some of the most radical recent ideas on the nature of jewelry are manifested in pieces that make no overtures to the look of machines, the feel of machines or the work of machines. The machine esthetic has been developing on the heels of the organic esthetic and it has also been wandering through a series of digressions and diversions. Recent work by David Tisdale, Emmy van Leersum, Paul Derrez and Susan Hamlet has left the idea of organic growth behind. Recent work by Marta Breis, Hilary Brown, Debra Rapoport and Lam de Wolf has not. The leave-taking has been half-hearted.

Function

The question of function is one of the definitive concerns of 20th century design. It is an intimate aspect of all levels of making. On a philosophical level, its relationship to jewelry has always been fraught with problems and often with heated discussion. Jewelry, after all, is not necessary to the physical welfare of the individual or collective human body. Setting aside the overworked discussion of psychological needs, the discussion of function in relationship to jewelry takes on an oblique cast. On the one hand it becomes an ideological discussion of the integration of body and decorations. On the other hand it becomes a pragmatic discussion of the relationship of body and object, an ergonomics of decoration.

How a piece of jewelry wears or sits on the body is the concern of ergonomics. The curve of the neck or wrist or waist determines the basic form of the decorative piece made for it. The mobility of the torso requires that the jewelry also have some mobility. Rings for fingers need to allow the hand to function in a normal manner. Such practical concerns about design function sound quaint today when artists are exploring jewelry forms that ignore the comfort or mobility of the body. But there was a time, the 60s and much of the 70s, when practical problems were determining factors in design.

New jewelry objects, those from the late 70s into the 80s, demand full attention for themselves. The relationship of the body to the object either is seen in terms of dichotomy rather than in reciprocity or is seen as only marginally important. Function is discussed from the point of view of the object rather than from the point of view of the wearer. The object functions intellectually.

Much recent dialogue on art is the dialogue by art about itself. The work functions on an intellectual level resulting in an ideological discussion, which in jewelry manifests itself through a pictorial mode. Don't Go Out at Night, Self Portrait with Structure and Straight Jacket, Training Fetish and, Love Object are titles of brooches by Bruce Metcalf and Fred Woell. Metcalfs pieces are images on a nearly flat surface that are best displayed by finding a body to ride on. Woell's work is more sculptural, but it does the same. These are minimally dialogues on function. They are primarily dialogues on imagery. These pieces are self-contained artworks that happen also to be wearable. The idea of the piece functioning in relation to a body has shifted into the idea of the piece functioning in relation to itself. The object is now considered entirely as iconographic, and it succeeds or fails on its merits as a painting or a sculpture. This represents an important ideological shift.

The discussion of ergonomics versus independent art object is more subtle than that concerning formal problems. Even when jewelry becomes an independent art object, it is still made to be worn and this necessary relationship to the body has various arenas of unease. Whether a piece should be volumetric or flat, echoing the body or using the body as a display surface is an essential dichotomy that is frequently made to find middle ground. A three-dimensional piece when worn against a body is a sculpture pushed against a wall. A wall may be the best place for a painting (a flat brooch), but a body is not, for the most part, a wall. The piece may then seek for a middle between the extremes and what is essentially bas-relief sculpture frequently results. Or the piece may speak directly to the volume of the body by wrapping around it and mimicking its contours. Practicality is not the issue here; ideology is. A discussion of line and volume, or draughtsmanship as it pertains to mass, ensues.

Draughtmanship around a body is draughtsmanship in space, three-dimensional drawing that relies on a living armature for successful display. It is an extreme position and it is most clearly reached by the work of Lam de Wolf and Caroline Broadhead. Their jewelry, dating from 1983, is among the most recent work in the Helen Drutt collection. These large-scale pieces are bold, nonergonomic and ephemeral. Their function is, indeed, intimately related to the body for they need a body in order to be complete. But the comfort and the ability of the body to function with ease is no longer an issue. The body has become much more than just a free ride for the object and much more than just a thing to be decorated. The traditional idea that jewelry serves the body has been reversed. The body has been made to serve the jewelry. The art object in terms of the body prevails. But, in a neat double twist, the body in terms of the mind claims the ultimate victory. The mind conceives the intitial jewel of adornment as an art statement and transforms it into a ritual garment, which is inextricably bound to a body, which in turn gives it its reason for being. In essence, the function of jewelry has been reversed and redefined.

In the broadest sense, jewelry is a collection of precious things very dear to one. An intense and discursive analysis has been brought to bear on the subject in the past 20 years. The wandering quality of the discussion does not mean that no conclusions have been reached or that new directions and sensibilities have not been found. But there has not been a steadily unfolding discussion, with premises agreed upon, developing into a new situation. For every direction of inquiry, there has been a counter direction and for every counter direction, there has been an oblique one. The result is a plurality; a plurality of styles, of ideologies and of definitions. Jewelry is still arguing.

Personal Notes on the Collection

During the 1960s my awareness of the modern crafts movement began to surface, leading me on an intense visual journey: looking at work, visiting artists and exploring studios. Frustrated by the lack of scholarship in the field, I began to search everywhere for information. My independent study course in modern crafts had begun. I was absorbed by these activities and despaired at the lack of information and absence of dialogue in the cultural community. At this time, the concept of forming a collection of modern jewelry was neither intentional nor was it a primary concern.

In 1964, I was the proud owner of a gold-plated circle pin from my high school days (probably purchased sometime in the late 40s) and my grandmother's cameo brooch, laced in platinum and diamonds, which was given to her by my father in 1918. The third acquisition was a replica of Queen Shubad's golden leaf necklace, purchased at the University of Pennsylvania Museum shop in 1956. I wore it with pride! A decade later I discovered that it had been made by Olaf Skoogfors.

In 1965, during a visit to Stanley Lechtzin's studio, a brooch nearing completion captured my eye. I had never seen a pin that incorporated the esthetic qualities of painting and sculpture, and it stirred me. Simultaneously, I experienced an intellectual encounter with the work of Olaf Skoogfors. Lengthy dialogues about nature, music, industrialism, socialism and constructivism followed, evoked by the search evidenced in his pins and pendants. Initially, my reason for owning them was to promote my newly born interest in modern crafts. No one could carry a vessel or chair into a meeting, but wearing a brooch was like being a living billboard. Jewelry acted as a catalyst for questions from museum directors, curators, acquaintances, students and strangers.

I remember delivering an impromptu lecture to a charwoman in a train station as she tried to understand the lyrical complexities of an Albert Paley brooch. At another time I was an unannounced guest lecturer during a flight from Philadelphia to Detroit because I was wearing an electroformed torque by Lechtzin. The recognition of these works caused continuous debate and inquiry, and it was important for them to have a walking educator.

In 1967, the Philadelphia Council of professional Craftsmen (PCPC) was founded. It was comprised of a group of 30 artists affiliated with the faculties of Philadelphia art colleges and universities, as well as several independent studio artists. As a founding member, I served as their volunteer executive director for seven years. During this time, exhibitions, panels and lectures were organized, including the first David Watkins/Wendy Ramshaw exhibition to be held in America. There was no NEA grant money for crafts, no funding and no courses in the history of modern crafts. When Philadelphia College of Art was unable to locate a lecturer for their proposed craft history course in 1973, it was requested that I organize my notes, stop lecturing on the streets of Philadelphia and accept the position.

With continuous independent research, this activity dominated my existence and brought me in contact with artists everywhere. In 1974, as the PCPC's goals began to be met (and due to the lack of regional exhibitions), the Helen Drutt Gallery was born. It was an attempt to provide the public with a forum for the crafts and a center for study. These activities naturally brought me into contact with significant works that had received little public response in terms of collecting, and I began to acquire them in order to "hold" history.

This collection reflects both the activities that were essentially part of my life in Philadelphia and the travel that the increasing interest in modern crafts ultimately demanded. The first acquisitions were Skoogfors, Lechtzin and Paley, who were in the U.S. When Claus Bury came here to lecture during the fall of 1973, he was my house guest. I had just made the decision to open the gallery, and my first acquisition was a gold and acrylic ring by Bury—a union of materials unique in this country. My knowledge of Bury's work came through Skoogfors and through the catalog of the "Dürer Five Hundredth Anniversary Exhibition" held in Nurenburg, Germany in 1970. The quest had begun. Acquisitions of the work of Gary Griffin, J. Fred Woell and Eleanor Moty began in the 60s and, continued into the 70s. Purchases from abroad continued with a Gerhard Rothman bracelet and a David Watkins neckpiece. This pattern continued through the 80s and began to include works by European artists.

"Modem Jewelry 1964-1984," as a collection, visually documents the dialogue that centered in Philadelphia during the last two decades. As a visual journey that closely parallels the professional life of its collector, it is a record of the taste of one's time, and I hope it will assist in the development of late 20th-century art."

- Helen Williams Drutt

"Modern Jewelry, 1964-1984: Collection of Helen Williams Drutt" was exhibited at the Montreal Museum of Decorative Arts, November 15, 1984-February 3, 1985. The exhibit will travel to the Honolulu Academy of Art, late January, 1986 and the Cleveland Institute, September, 1986. Further travel schedule in preparation for the United States and abroad. A catalog of the exhibit is also in preparation.

You assume all responsibility and risk for the use of the safety resources available on or through this web page. The International Gem Society LLC does not assume any liability for the materials, information and opinions provided on, or available through, this web page. No advice or information provided by this website shall create any warranty. Reliance on such advice, information or the content of this web page is solely at your own risk, including without limitation any safety guidelines, resources or precautions, or any other information related to safety that may be available on or through this web page. The International Gem Society LLC disclaims any liability for injury, death or damages resulting from the use thereof.

The All-In-One Jewelry Making Solution At Your Fingertips

When you join the Ganoksin community, you get the tools you need to take your work to the next level.

Trusted Jewelry Making Information & Techniques

Sign up to receive the latest articles, techniques, and inspirations with our free newsletter.