Architectural Hardware Today

Some 20 years ago, the Victoria and Albert Museum in London sponsored "Towards a New Iron Age, "aninternational exhibition of contemporary wrought ironwork. The thesis of the exhibit was that while ornamental ironwork "had remained in the grip of the historical pastiche" for much of the twentieth century, it nonetheless was a discipline that offered enormous potential for modern design. The pieces shown - lighting, tools, and both interior and exterior architectural ornamentation - illustrated how this antique discipline could offer forms "appropriate to the tastes and attitudes of our own time."

10 Minute Read

Some 20 years ago, the Victoria and Albert Museum in London sponsored "Towards a New Iron Age, "aninternational exhibition of contemporary wrought ironwork. The thesis of the exhibit was that while ornamental ironwork "had remained in the grip of the historical pastiche" for much of the twentieth century, it nonetheless was a discipline that offered enormous potential for modern design.

The pieces shown - lighting, tools, and both interior and exterior architectural ornamentation - illustrated how this antique discipline could offer forms "appropriate to the tastes and attitudes of our own time."

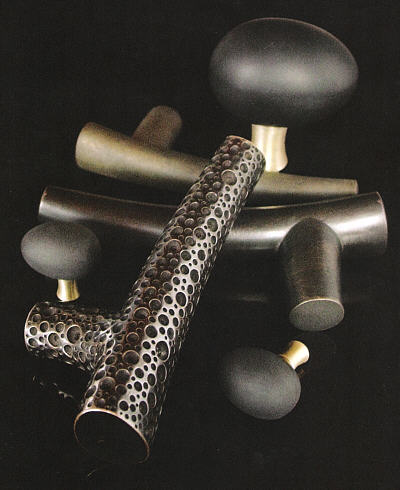

| Ted Muehling, Levers and Knobs, 2003 Brass, brass and crystal Manufactured by E.R. Butler & Co. New York |

Today, those sentiments seem quaintly outdated, as it is widely accepted that architectural metalwork of all kinds, and not only ironwork, has contemporary relevance. The work of designers from varying disciplines brings new perspectives to the field: while jewelers may work with an intuitive awareness of human form, architects are more driven by the shapes and rhythms of the built environment, and other metalsmiths may bring an engineering and more technical finesse to this field. Seen together, all of these handles, hinges, knobs, pulls, and other artifacts reflect an area of design that speaks to our time with increasing resonance.

| Fletcher Coddington/ Arrowsmith Forge Lock Box and key 1999 Bronze, 5 x 7″ |

While innovation in ornamental hardware may have been more limited during the Modern period, the creativity encountered today is the result of something more than the predictable cycles of style and aesthetics. Designer Jennifer Coppel comments, "Because of its function, hardware is a tool, a tool that becomes an extension of our hand. Extending ourselves in both the physical and intellectual sense is what excites and challenges most hardware makers today." Coppel may seem to he stating the obvious, yet in the last two decades, our growing preoccupation with the intangible seems to have whet an appetite for the tangible. In the Information Age, when human communication at large has become a more elusive and ephemeral enterprise, looking for that extension of the hand, that sense of physical connection, may be a natural and intuitive human impulse. And certainly metalworkers are skilled in forging such connections.

| Jennifer Coppel, "Leg Series" 1999 Bronze, Dimensions variable |

Consider Coppel's own work. Now a product designer for Excell Home Fashions, she owned and operated her own company, Eden Hardware, in Detroit from 1999 to 2001, and she continues to offer some of that work on a limited production basis. The "Leg Series," available on a custom basis for orders greater than 20, speaks to the sensuality of an artifact that connects a person to a building. Coppel explains, "The crispness of the concave escutcheon heightens the organic sensual quality of the handle. This intentional contrast is derived from the seductive image of a woman's leg emerging from a car, an image we so often see in movies and advertisements."

Fletcher Coddington of Arrowsmith Forge in Millbrook , NY , brings an entirely different perspective to hardware. His work highlights how this area of metalwork often goes well beyond the decorative to recognize highly complex technical and mechanical challenges. Throughout the 1980s and 1990s, Arrowsmith produced a high volume of production work lamps, hardware for outlets including Pierre Deux in New York City . In more recent years, with an economy less robust and NAFTA assuring cheaper production overseas, the studio has turned to custom work, much of it architectural hardware. Coddington is a designer for whom the technical and aesthetic demands of a project are often indistinguishable. His work might range from repairing a nineteenth - century English telescope damaged on 9/11 to fabricating equipment for the local highway department to creating all the hardware and metalwork for an estate wine cellar. As he puts it, "You get a project, and you figure out how it's going to work. Then you make the tools for it. Or maybe you make the tools to make the tools. Or the tools for installation."

Among his most challenging work is his custom architectural hardware, where concerns about weight and balance are as significant as any aesthetic consideration. His design of a brass hinge to support an eight - quadrant, twenty - one inch round window, though seemingly prosaic, was a highly elegant piece of problem solving. The hinge needed both to limit the openings and have an offset so that the window wouldn't hit the casement when open. The problem, Coddington explains, was that hinges long enough to support the weight of the window were all straight, so he had to fabricate an eleven inch piece of curved brass.

| Fletcher Coddington/Arrowsmith Forge Window Hinge and Latch 2003 Bronze; Hinge height 16″ |

Jeweler Gabriella Kiss brings a different sensibility to the discipline. A nationally known jeweler, Kiss looks to the natural world for her imagery - fragile insects, serpents, delicate leaves and petals are rendered in 18k gold and precious gems. Her work also often resonates with personal references. The mahogany "four - generation bureau" in her son's room was built by her husband, furniture designer Chris Lehreeke with the hardware fashioned by Kiss from thin sapling branches a grape vine, apple tree, plum tree, pear tree - - planted by her grandfather on property now her father's. Cast in bronze, the slender branches read as sculptural extensions of her jewelry.

Kiss explored similar naturalistic imagery on a much larger scale for Takashimaya, the Japanese department store's flagship space on Fifth Avenue . The sixth floor atrium opening onto the fourth and fifth floors has been encircled with a delicate hedge of interwoven sapling branches, a four - and - half foot - high thicket of sumac, cherry, and birch, cast in bronze. Interspersed among the branches are a sequence of 18k gold butterflies that appear to have alighted from some transcendent migration. While working as a barrier from the floors below, the piece appears as a crown of sorts, jewelry for architecture indeed.

| Gabriella Kiss Atrium (Takashimaya, New York), 2001 Bronze, 18k gold; 4 1/2 x 8″ |

Such work has understandably elicited the interest of architects and designers, and among those interested in working with Kiss is Rhett Butler, who owns and runs E. R. Butler & Co. in New York City , now through its acquisitions the oldest hardware company in the country. Butler established the company 15 years ago, and since then has acquired a number of older companies, among them the W.C. Vaughan Collection of early American and Georgian period hardware and the E. & GM Robinson Crystal Collection of early American hand ground crystal knobs. Along with his comprehensive Collections of hardware, Butler has amassed a library of some 5,000 books, trade catalogs, and original factory manuals, and his primary interest now is in completing some of the period collections he has purchased.

Butler also works with contemporary American architects and designers for custom work. Among the customized hardware the company has produced are such curiosities as a brass and wood lever handle reinvented by Merry Despont from an antique French dagger for Bill Gates and a lever handle sheathed in ermine designed by Benjamin Noriega - Ortiz for rocker Lenny Kravitz. When asked whether such custom work has wider applications, Butler reports, "Very little custom work is appropriate for larger production. Most of it is pretty project oriented."

That said, Butler is also working with other contemporary designers to produce limited production lines. Another of Butler 's designers is Ted Muehling, the well - known jeweler who in recent years has designed porcelain tabletop accessories for Nyphenberg. Muehling is known for the way in which he reimagines and reinvents ordinary - a tiny pinecone appears to have been washed in silver, a kernel of rice spun in gold. The language of form is concise, direct, and straightforward. Without necessarily relying upon precious metals or costly gems, all manners of natural forms - pods, cones, kernels - become something else, poised in some nether world between the literal and the abstract. A series of candlesticks he designed for Butler are based on three shapes - egg rod, and trumpet. But whether it is jewelry or tabletop accessories, Muehling's work tends to reflect his training as a jeweler; there is a deep connection with the human form, an engagement with and awareness of the body.

Longtime friends, Muehling and Butler have an easy collaboration which the latter characterizes by saying "I tell him to apply this or that technology, and he'll bring some whole new aesthetic back to me." The two have traveled to the annual Tucson Gem Show, and Butler recalls, "His interest is in buying stones. For me, the interest is in the technology of making jewelry, and how that can relate to hardware." The recent products of this collaboration include brass lever handles with a perforated texture that evokes a piece of coral; and rounded oval knobs, in the shape of small eggs, that have been made from pulverized crystal. "it has the qualities of black jade," says Butler , "And you could make it out of black jade, but Ted has a realistic view. He shies away from things being too expensive. He wants people to buy them."

If jewelers bring both a sense of precision and an intuitive awareness of the body to the design of hardware, architects, by profession, are more connected to what lies on the other side of this connection, which is to say, the building. Valli & Valli, the Italian manufacturer of architectural hardware, established its subsidiary Fusital in 1976 to involve designers and architects in the design of hardware. Since then, the company has worked with such architects as Michael Graves, Norman Foster, Vice, Magistretti, Richard Meier, Renzo Piano, and Aldo Rossi.

Foster's words bring us full circle to Jennifer Coppel, whom he echoes when he states, "The handle of a door could be linked to architecture in miniature. It has to work well but it must look good. In another sense it is an important part of the furniture in a building - one of the few points of physical contact."

What all of the Fusital lines show us is that this point of physical contact can be simple and straightforward in the manner of Richard Meier's elegant geometries, in which curves, rectangles, and squares may reduce the architectural principals of a building into a handheld scale. Or it can be one that more fully engages the senses: the soft, multiple curves of a brass lever handle from the workshop of Renzo Piano accommodate the curve of the hand and give a place for the thumb to rest, all with a subtle sensuality.

A similar sensitivity to the hand's predilections informs the hardware produced by FSB, one of Europe 's leading manufactures of architectural hardware. Established in Germany over 120 years ago, the company now has offices around the world. The firm's success rests on a combination of innovative engineering and aesthetic principles articulated by the company's design director during the 1950s, Johannes Potente. Potente's "four rules of good grip" describe the elements of an ideal lever: a guide for the thumb, a hollow for the forefinger, a support for the ball of the thumb, and a volume to fill the palm. Potente's principles still guide the company's production today, and his own refined lever designs are now part of the Museum of Modern Art 's permanent collection.

FSB continues to enlist the talents of recognized designers such as Philippe Stuck to develop complete hardware programs, consisting of matching levers, window handles, cabinet knobs, and doorstops.

A reasonable person in 2004 might be forgiven for finding a preoccupation with the design of doorknobs and handles a frivolous matter. Yet as Piano states, it is a place where human contact begins: "A door handle. Sometimes, one caresses it gently in order to enter without noise, to avoid waking the baby. Sometimes one grabs it with an imperious gesture to take possession of the room …. There is no gesture that is repeated with greater intention and there is no object of our daily life which requires more participation; or one on which our mood is so much projected." Surely this is what Coppel refers to when she speaks of these tools that help us extend ourselves. And what she and Piano, along with all these architects and designers, suggest most clearly is that the means with which we are connected to the built environment are as infinite as the sensibilities forming them. The ways in which we take hold of the built world are limitless - they can begin anywhere and everywhere.

| Philippe Starck Door Handle #1991, 1992 Anodized Aluminum Handle length 5 3/4″ Backplate diam. 7 1/4″ Manufactured by FSB Franz Schneider Baker GmbH, Germany |

Akiko Busch lives in the Hudson Valley and writes about design for a variety of publications.

You assume all responsibility and risk for the use of the safety resources available on or through this web page. The International Gem Society LLC does not assume any liability for the materials, information and opinions provided on, or available through, this web page. No advice or information provided by this website shall create any warranty. Reliance on such advice, information or the content of this web page is solely at your own risk, including without limitation any safety guidelines, resources or precautions, or any other information related to safety that may be available on or through this web page. The International Gem Society LLC disclaims any liability for injury, death or damages resulting from the use thereof.

The All-In-One Jewelry Making Solution At Your Fingertips

When you join the Ganoksin community, you get the tools you need to take your work to the next level.

Trusted Jewelry Making Information & Techniques

Sign up to receive the latest articles, techniques, and inspirations with our free newsletter.