Objects in Space: Future Arena for Silversmiths

5 Minute Read

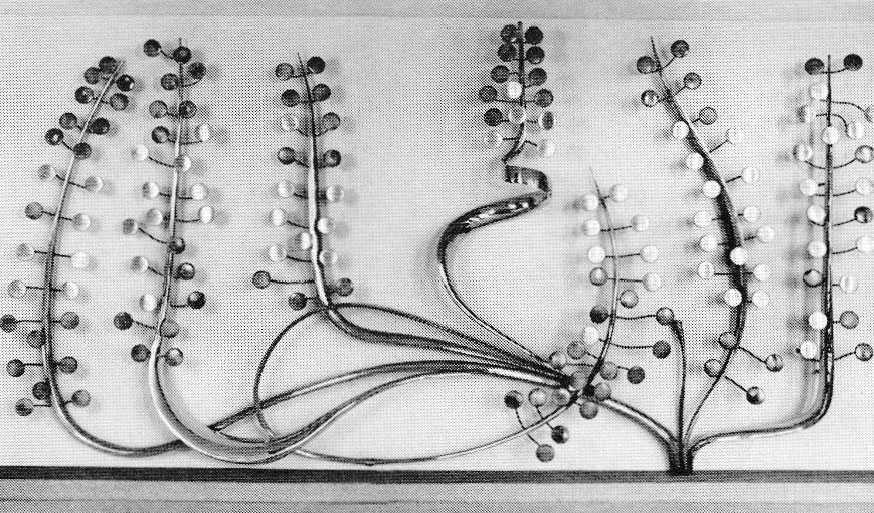

An object in space is exactly what the name implies, namely one which by design has left the company of its table or wall bound predecessors, like coffee pots and sconces, and assumed the role of an object without a function. It has taken up the role of an image of containment to invoke ideas and conjure responses in concert with the observer. Various positions invoke different responses. Suspension usually renders the most suitable ambience, and the ultimate in the choices of form may now play the long-lost game with internal spaces.

Why such a radical lump from the recognized formality of functional silversmithing? Perhaps the most obvious practical reason can be found in the change of mores, habits and customs. The consumer society is less likely to use silver vessels any more due to the trouble of serving, cleaning and caring for such paraphernalia, let alone the cost. Heirlooms end up in glass cabinets only to be looked at, just like flintlock rifles on the wall, never to be used again. However, silver need not be excluded from the environment of a contemporary person. Objects for contemplation have long been a part of home surroundings. And silver with its inherent value, just might embody the ideas and intent of its maker longer than one made of cheaper material.

Another reason for silver's use, much closer to the heart of a creative metal artist, is the freeing of the material totally for the purposes of expression. There need no longer be a well pouring spout or a comfortable handle as design requirements. The work can be wholly expressive in its form and the "scratches" on it.

Consider the ultimate in design meeting the requirements of function, and you'll have, as the prime example, modern stainless steel eating utensils. To change anything but the surface scratches in the best-designed spoons, knives and forks, there must be a change in their use. People's habits must change. Utensil designs have met every requirement put on them. They can not be improved until their usage changes.

Yet another valid reason, and perhaps the best one from the esthetic point of view, is the final riddance of the volumetrically superior rotation form. Such forms might be comfortable as stabilizers of our otherwise chaotic lives, but to seek nuances of noncyclical expression in such clockwork precision seems as futile as it ever was. Cyclical recurrences are well understood, and are "old hat." Such movements are predeterminable and totally devoid of any surprises. To promote the esthetic value of a rotation form is tantamount to closing one's eyes in the face of irrefutable evidence that such a system is finite. There are seven basic rotation forms whose multitude (seven raised to the seventh power) gives us a sweet number of millions, which seems to imply an infinite number of choices But this is only a camouflage; the basics still spell "finite."

Ever since the invention of the wheel, we have been esthetically imprisoned by the rotation form. We seem to find endless streams of beauty in it. Yet its products are everywhere and are literally holding us hostage to renew our loyalty to its values, over and over again. Any aspiring artist would be horrified to find that his/her options are already taken, and that there are no new ones available, all innovations having already been done.

Are objects in space needed? No, not in the same sense as the eating utensils, but they are desirable in the same sense as any art objects are. The desire grows from sources other than functional needs. And yet, part of that desire is already planted in the human mind. It isn't so strange to think that environment, in its form-oriented mode, has much more of an influence on a person's psyche than peacock feathers hanging from thumbtacks on a flat, sterile wall.

Form, by itself, has profound influence as far as human environment is concerned. Human history tells us of more devotion, more meaning, deeper belief whether religious, political or other human relations put on the forms, symbolizing them, than two-dimensional ornament (i e.. scratches on just any surface) of any kind.

We, the silversmiths, know very little of form. How do we identify forms? How do we develop new forms? Are there any new forms? What is the psychological effect of a given form on a human? Is there anything to the psychological effects of "touchstones?" Form versus color what to make of it? What if they're combined? Is it time to have a form language? At this time in 3-d education, there is no known methodology to generate, develop or identify three-dimensional objects for esthetic or symbolic effect.

If a horizontal line is more tranquil than a vertical line, what is the equivalent difference between a sphere and the most jagged shard, a quadrahedron? If we associate a message of any kind to a dotted line, can we dismiss the energy of a helical, tangible object? Primary material, I agree, but the issue is whether or not 3-d art has a content As one writer queried, "Is subject matter or content still insignificant in relation to form? Are representational images still taboo?"

I'd have to resort to an age old cliche: "Yes, the world is round, and reality is concretely under you, all else is illusion." Form can speak louder in more fundamental terms, thus having more of a content than scribbles on the sidewalk or the ephemerality of "Kilroy." The 3-d artists, especially the versatile silversmiths, can capture a whole new era of contribution to art, life and that old profession.

Two-dimensional ornament is specific ephemeral and delightful for today. But think—if you make something out of durable material, it might last forever, and tell of you and your times on this earth. Stainless steel is okay, silver is not bad, gold is eternal, and the thought of man s message is yet older.

Heikki Seppä, July, 1984 while ruminating in the Finnish woodlands

You assume all responsibility and risk for the use of the safety resources available on or through this web page. The International Gem Society LLC does not assume any liability for the materials, information and opinions provided on, or available through, this web page. No advice or information provided by this website shall create any warranty. Reliance on such advice, information or the content of this web page is solely at your own risk, including without limitation any safety guidelines, resources or precautions, or any other information related to safety that may be available on or through this web page. The International Gem Society LLC disclaims any liability for injury, death or damages resulting from the use thereof.

The All-In-One Jewelry Making Solution At Your Fingertips

When you join the Ganoksin community, you get the tools you need to take your work to the next level.

Trusted Jewelry Making Information & Techniques

Sign up to receive the latest articles, techniques, and inspirations with our free newsletter.