Metalsmith ’95 Fall: Exhibition Reviews

37 Minute Read

This article showcases various exhibitions in the form of collected exhibition reviews published in the 1995 Fall issue of the Metalsmith Magazine. This features Betty Cooke, Detlef Thomas, John Prip, and more!

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

ALCHEMY: Metals Made Precious Lynda Watson-Abbott's 25 Years of Influence

The Pope Gallery

Santa Cruz, CA

March 5 - 31, 1995

by Susan Kingsley

The stated purpose purpose of "ALCHEMY: Metals Made Precious Lynda Watson-Abbott's 25 Years of Influence" was to honor Lynda Watson-Abbott and recognize the successful jewelry and metalsmithing program she created at Cabrillo College and to mark her retirement after twenty-five years. An alcove of the gallery was devoted to her most recent work, a series based on barbed wire variations. A statement by students paid tribute to her enthusiasm, dedication, and belief in each individual's creative process.

Additionally, the exhibition affirmed the value of community-based education. Watson-Abbott's long tenure at Cabrillo has resulted in a community positively riddled with artist/jewelers. Unlike art school and university programs which are intended for a population of young students in degree programs who graduate and leave, community colleges serve a wide variety of different needs, values and goals and students are generally there to stay. Included in this exhibition were works by artists in their early twenties and artists in their sixties, some who had gone on and earned bachelors and/or masters degrees and some who took up metalsmithing after retiring from other careers, some who make jewelry in their spare time and some who earn their living doing ACC shows.

Group exhibitions frequently fail to satisfy. One is often left remembering only a few outstanding pieces along with a hastily formed opinion about whether the show lived up to to its stated curatorial purpose, which is frequently uninteresting to begin with. This exhibition was an exception for a number of reasons.

The 2500-square-foot space of the light-filled Pope Gallery was devoted exclusively to this exhibition, which completely filled it. The work was displayed in specially-made, shallow, shadow-box cases backed with primer-gray sprayed foam. The gallery walls were painted sage green for the exhibition. Despite the wide range of work and styles, the installation, which also included conscientious attention to the grouping of works and to lighting, provided visual continuity. Larger work was displayed in the storefront windows and on island pedestals, providing an easy transition to the small scale work in the cases.

Like most group exhibitions of contemporary jewelry and metalsmithing, a wide range of materials and processes was in evidence. Steel, bronze, copper, and plastic were used in addition to the expected precious metals and gemstones. Processes included anticlastic raising, casting, die forming, electroforming, enameling, etching, photo-etching, raising, and reticulation; as well as fabrication, in which there seemed be be a universal proficiency. Although the majority of work chosen was in the category of wearable jewelry, hollowware, sculpture and furniture was also in evidence. Objects were well-crafted, though certainly not of a single aesthetic.

The exhibition was curated by artist and metalsmith Doug McDonald, also a former student of Watson-Abbott. He was assisted by Jamie Abbott, Carol Ball, Shelby Graham, Jane Gregorius, Susan Hoisington, Prudence Masseth, Angela Marise and Lydia Tea Walking. Watson-Abbott provided the starting point, a list of around 200 students with whom she had stayed in contact. McDonald began with the standard procedure of requesting slides from the artists. He soon realized, however, that this approach was not suitable. Much of the work he expected to see had either not been photographed, or the slides did not reflect the quality he knew existed in the work. McDonald worked assiduously tracking down, piece by piece, this high quality exhibition. Although most of the work was for sale, some of the artists do not regularly make art for exhibition or the marketplace. Their work is seen only when being worn in the community. If there was anything that distinguished the jewelry in this exhibition, anything that tied it to Santa Cruz, it was a bit of humor, a while of irreverence and the personal nature of the majority of the work. The artists, each in their own way and without conceit, pursue art-making as an important part of life. In addition to teaching techniques of metals, which she apparently did very well, Watson-Abbott nourished in her students a desire to continue making art.

Group exhibitions frequently fail to satisfy because they lack a harmonious mutual understanding, a sense of shared purpose. The conclusion of Watson-Abbott's twenty-five-year teaching career provided an opportunity for celebration and an opportunity for this community to observe and re-affirm the value of what they have had. Too often excellence and success in the fields of jewelry and metalsmithing are defined only by how well work can be photographed, how often it is published and how profitably it can be marketed. This exhibition was not only about a community college program, but about the idea of art being a part of lives and a community.

Susan Kingsley is an artist/metalsmith in Carmel, California.

Artists included in the exhibition:

Lynda Watson-Abbott

Holly Bachman

Carolyn L. Ball

Karen Barker

Judy Bettencourt

Judy Dykstra-Brown

Rebecca Bushner

Lotte Cherin

Ta Ta Chook

Michael Dunn

Judy Foreman

Elizabeth Golden

Shelby Graham

Blanche Greenberg

Geraldine Gyger

Betty Heald

Jill Henry

Gerhard Herbst

Elaine Heyman

David Holder

Charles H. Kirk

Elena Laborde

Jessica Phoebe Lee

Scott Lindberg

Angela Marise

Prudence Masseth

Sherry McDermott

Doug McDonald

Joan Mitchell

Lori Mitchell

Sean M. Monaghan

Junko Nakazawa

Andrea O'Donnell

Kris Patzlaff

James C. Payne

Merrylee Rae

Jose Santana

Liza Scully

Norma Sheilds

Patrick Stafford

Marion Stegner

Dan Telleen

Christie Thomas

Lydia Tea Walking

Carol Webb

Larry and Katherine White

Linda Wulfsberg

Design • Jewelry • Betty Cooke

Meyerhoff Gallery

Maryland Institute College of Art

Baltimore, MD

June 2 - 25, 1995

by Bruce Metcalf

Betty Cooke graduated From the Maryland Institute in 1946, intending to be a sculptor. She has remained in the Baltimore area ever since, not as a sculptor, but as a jeweler with a large and loyal following. The Maryland Institute mounted a career retrospective of her work in June, 1995 (unfortunately, still a rare occurrence for a jeweler of any caliber but still an interesting opportunity to contemplate a life's work given over to jewelry).

In 1946, cutting-edge craftspeople talked about good design. This idea contained echoes of the Arts & Crafts reform movements, in that converts believed they could improve the quality of life by bringing higher standards of design to the general public. In jewelry, the look of the handcrafted object was suppressed in favor of slick, polished surfaces; ornament was restricted in favor of smooth, rounded forms; and the doctrine of truth to materials held sway. It's clear that Betty Cooke was a true believer, and she never strayed far from the ideology and style of a late 1940s designer.

And yet, her work resists being dated. So much '40s and '50s jewelry now looks technically primitive and conceptually shallow: most of us have seen far too many flat kidney-shaped brooches and chains of forged round links. There were a few clichés in Cooke's exhibition: some starburst brooches and rings with single tall cabachons among them. But most of her jewelry has a wonderful sense of subtle irregularity and understated elegance that can never be reduced to cliché. She also knows how to use the visual surprise: an asymmetrical stone or a sudden shift of thin to thick line that keeps most of her work remarkably fresh. Cooke shows how, in the hands of a skilled designer, the doctrine of good design remains useful.

The audience at the exhibition opening demonstrated how responsive people have been to Betty Cooke's approach. Every third woman was wearing at least one Cooke necklace, ring, bracelet, or set of earrings. Evidently, good design has found an appreciative public in Baltimore. Furthermore, every woman I asked knew exactly when and for what reason she had acquired each piece of jewelry. It was obvious that Cooke's jewelry is much loved, because people have added their own layers of sentimental meaning.

This process of investing jewelry with private importance is poorly understood and is often dismissed as trivial, but it is crucial to our understanding of craft in the late 20th century. People don't buy craft out of need, they buy it out of love. So, how and why do people project their passions into an object? It's a difficult question, but Betty Cooke appears to know the answer. Cooke's jewelry is familiar and undemanding, but inventive at the same time. For instance, she appeared to expand her scale in the early 1970s, perhaps influenced by the oversized necklaces produced by Al Paley, Stanley Lechtzin, and others. But instead of commandeering the entire upper torso like Paley and Lechtzin did, Cooke made slender chains of linked tubing that hung both in front and in back. These chains occupied no volume, demanded no concessions from the wearer, and looked smashing on a formal dress. So, her clients could partake of the thrill of wearing radical jewelry, but still not overstep the boundaries of taste or function. It was obviously a successful strategy: I saw at least twenty of these chains being worn at the opening.

Betty Cooke never received the same national recognition as other jewelers of her generation, like Sam Kramer or Ed Weiner. This lack of recognition is unfortunate, because her work has much to say about the raison d'etre for contemporary handmade jewelry. And, as the enthusiastic response of her clientele shows, she can probably teach all the art jewelers a thing or two, as well.

Bruce Metcalf is a jeweler from Philadelphia.

Detlef Thomas

Jewelerswerk Galerie

Washington, DC

April 27 - May 18, 1995

by Alyssa Dee Krauss

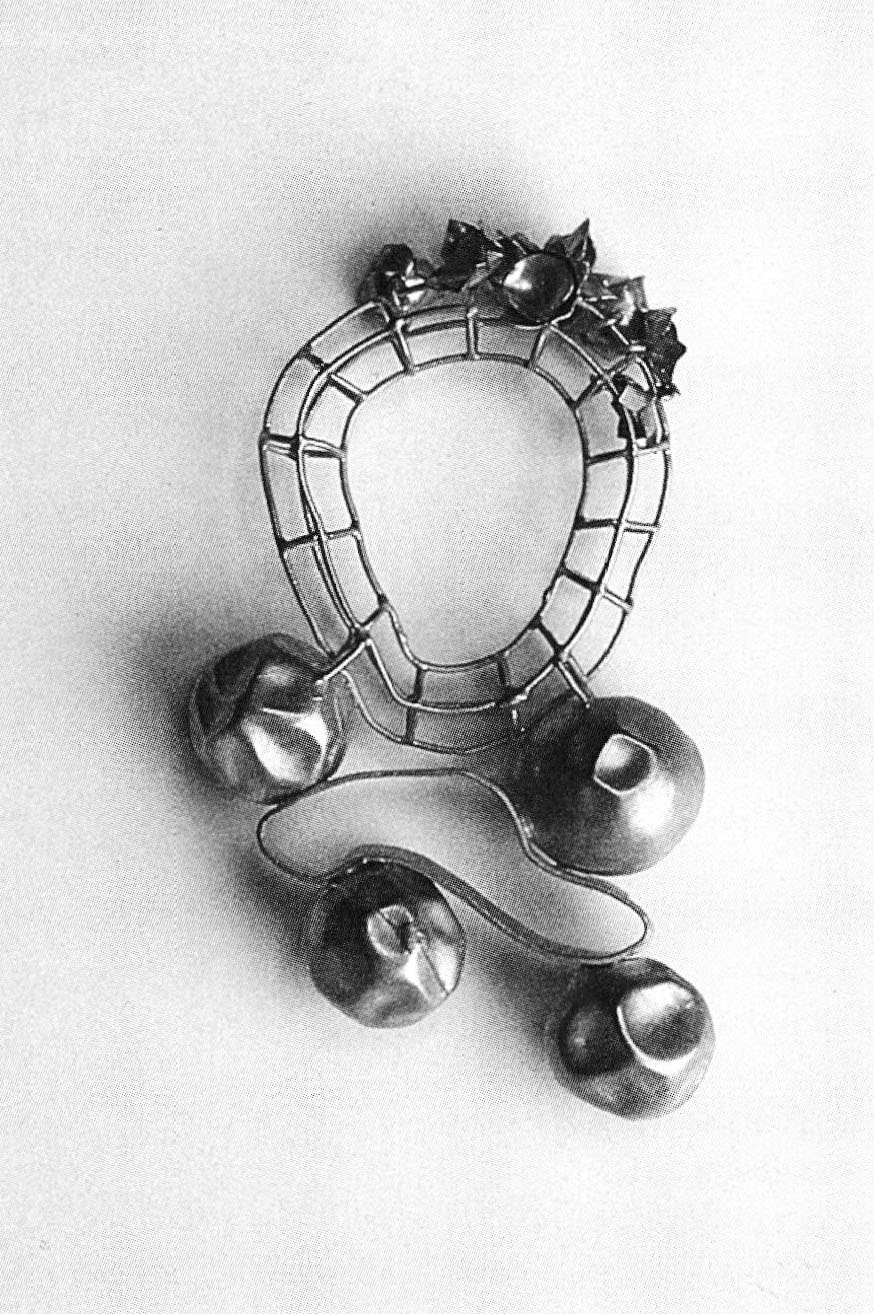

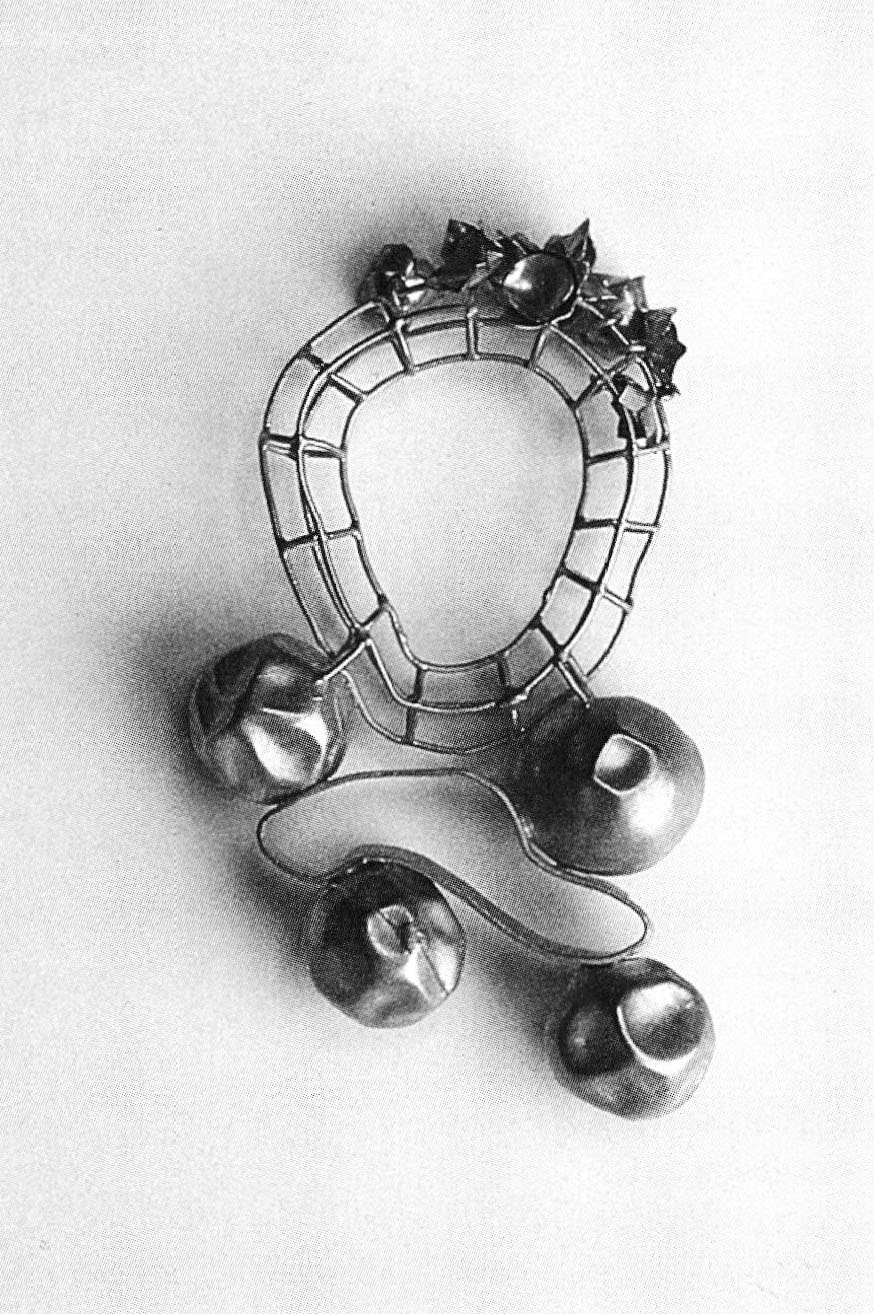

Detlef Thomas's new work makes fun (out) of serious jewelry. In this series, Thomas imposes chaos upon order, bringing poetry to geometry and a playfulness to technical mastery. He alludes to man and nature, technology and nonsense. Formally, the work perpetuates this mood, humoring the eye and transforming gestural, linear graphics into three-dimensional objects.

Thomas's older work was mainly concerned with overdoing ornamentation, though he also constructed a bunny rabbit ring (whiskers and all) out of 18k. In his new series, Thomas abstracts and punctuates this irreverence and whimsy by constructing highly exact geometric structures and then mashing, twisting, and distorting them. The precious materials, the refined techniques, and the intricate, geometric, architectural constructions are all quite serious; yet, the treatment of these elements is entirely frivolous. Thomas pays fastidious attention to detail and then negates that precision by smashing the work, or leaving a solder spill. It seems as if he treats the same piece with utmost respect and flagrant disregard (although when the work is completed, it has the kind of visual integrity that makes it hard to imagine any bend, distortion or sloppiness as truly unintentional).

Is it a mockery of the pristine Late Modernist Formalism rampant in much of contemporary German work? Is it a reaction to the rigid training of the Goldschmiedelehre? Is Detlef Thomas making fun of serious jewelers, the commercial jewelry industry, his own past work, or the aesthetic itself? Or, is he just having fun? (One of his pieces is a very commercial, mass produced granulated silver ring that Detlef found in the street, took home, and smashed with a hammer.)

Thomas's playfulness is not limited to the conceptual realm. He instigates a dynamic between volume and mass in his large, extravagant pieces that are, paradoxically, weightless and delicate. He teeters a tall, Gaudiesque skyscraper form on a thin wire shank with a fraction of the visual weight of that which it supports; like balancing the Empire State Building on a Hoola-hoop.

By far the most interesting formal attribute in his work is the linear expression and gesture normally associated with drawing. He remarkably captures this quality in his distorted wire forms. At first glance, the fragile skeletal structures really appear to be spontaneous sketches reproduced in metal. On a closer look, however, the former rigidity of these lines and the method behind their madness, is revealed.

When these strictly arranged wire forms become warped and bent, Thomas transforms the geometric into the biomorphic, and brings each piece to life. He improves upon what was man-made and ordered, with what is natural and disordered. He produces vibrant, gestural lines from stoic, Euclidean ones. He creates a visual tug-of-war between chaos and order. It is the residue of this rational thinking still visible through the now entangled jumble that gives Thomas's work its poetry, its sense of history, and its many layers of meaning.

Detlef Thomas's new jewelry is sculptural, though still appropriate to its medium because of its irreverent use of precious materials and traditional jewelry making techniques. In this series, the medium, materials, forms, and processes all converge to strengthen and support his concept. He manipulates his materials into metaphors and he achieves a refined aesthetic throughout. This exhibit sets a poetic example of what jewelry can be.

Alyssa Dee Krauss is a metalsmith, who resides in Mount Vernon, NJ.

Double Vision

Gallery I/O

New Orleans, LA

March 20 - April 10, 1995

Charles A. Wustum Museum of Fine Arts

Racine, WI

September 17 - November 5, 1995

National Ornamental Metal Museum

Memphis, TN

December 17, 1995 - February 11, 1996

The Arkansas Art Center

Little Rock, AR

April 21 - June 2, 1996

by Deb Stoner

Imagine this experience. It is the opening night of the New Orleans SNAG Festival's gallery tour/endurance contest to seven galleries hosting special exhibits of interest to metalsmiths and jewelers. Seeing any exhibition under these circumstances is bound to not serve the work well. One views the work in a horde of other somewhat interested folks packed into a hot, bustling gallery where seeing the work is one goal, seeing one's friends is the other. But, often, it is the way an exhibition is seen by the majority of its audience.

You walk into Gallery I/O, a small, very crowded, and vivid commercial gallery space. On the wall to your right is a framed curator's statement. You read first about the exhibition "Double Vision" curated by Robert Ebendorf and Thomas Mann, and then about "Crossing Boundaries: Contemporary Jewelry-America, Europe, Australia' organized by Helen Drutt. Oddly there are two completely different exhibitions in this single space. You vie for position in front of the cases filled with jewelry. There are artists' names printed in small black letters taped to the Plexiglas cases: you look at the names and the order in which they are presented and attempt to match them up with the work. If you know the work, you can usually connect the dots. When confronted with unfamiliar work, the labels confuse. You realize at some point that the work in cases that divide the length of the gallery are the familiar objects shown in Helen Drutt's lecture that morning, and indeed, a large, but obscurely placed sign overhead indicates that this is so. "Double Vision" is spelled out in large letters on one wall to indicate that the wall cases contain work of that show. And the pieces along the other wall? Those must be the non-collaborative Part of the "Double Vision" show. You've gone through half of the gallery before you even know how this works.

The jewelry is placed on props prominently stamped "MANMADE", props that call for the viewer to make assumptions about or reflections on the jewelry or objects that the props hold. A bracelet by Heinz Brummel and Cheryl Rydmark is held by an elaborate bronze device that is larger than the bracelet itself. I stood nearby listening to people's comments as they contemplated this object. I plucked the bracelet off its prop, breaking implicit gallery rules ("Don't touch!") and several people gathered: "Oh! I didn't know that was a bracelet!" Whose responsibility is this? The viewer, for not getting the message? Neckpieces were displayed on large bronze plaques with curved holders that hold the piece out from the wall. These are effective mounts for showing the three-dimensional quality of the necklaces, but they force the viewer into making the distinction between the beginning and end of the piece, and the beginning and end of the prop. After seeing two or three such pieces, one understands how they are meant to work, and the props become merely the props that they are meant to be. The only person's work that is well served by this display system is Thomas Mann's. Designed for his work, the mounts display it, nay, enhance it, well.

I returned to an almost empty gallery the next day and spent three hours with the exhibition, looking at each piece with effort, slowly and with contemplation, trying to understand each piece as well as the show as a whole. I introduced myself to the woman in charge of the gallery who assured me that she could answer any questions I might have. I told her I was writing a review so she would not be confused by my intentions. My first questions were logistic: we walked to the first case and I asked: "Which of these five pieces are done by Teri Blonde and which are Bobbie Suet?" She laughed, and in a loud stage whisper said: "Well I probably shouldn't tell you this, but they are the same person. There is no Bobbie Sue." Now, I should make it clear that I love a good prank. A collaborative show with forty North American metals artists; but really it's 39. Ha ha? The accompanying catalog essay makes no mention of this, indeed it treats the work of this collaborative team of Teri Blonde/Bobbie Sue with all seriousness and importance. The number of artists in the exhibition is repeatedly stated as fact throughout literature about the show, and one has no reason to believe that this fact may be fiction. Perhaps if Teri Blonde/Bobbie Sue's work were more interesting and less derivative of North American narrative art jewelry done better by artists represented in the same display case, I would be less offended by this prank. I fantasized, hoping to make the whole thing worthwhile: split personality? sex change/transition personality, hey we're in New Orleans? Work so cutting-edge that no one in the world is worthy of collaboration with this avant garde artist? But none of these scenarios seemed true, and I am still irked by the sham, less trusting of the curator's intentions.

I looked at each piece in the exhibition as the cases were opened, and I handled some of the jewelry. I love this part: I tried things on, I touched objects to understand them. I played with Didi Suydam's and Joan Parcher's elegant neckpiece and understood the act of filling the hollow pendant with its chain to create a lovely sculptural form in addition to its success as beautiful jewelry. I'm lucky; I held Gary Noffke's and Rob Jackson's heavy silver ladle, to find the balance, to appreciate how the piece felt; I found hidden sapphires that one would only discover when using the piece.

I contemplated Jill Slosburg-Ackerman's paintings (did anyone else even see these two pieces, displayed on a wall, one above another, just before the entrance to the gallery?) and Joe Wood's three wire objects displayed in wooden presentation cases labeled "Harmony", "Logic", "Deceit", and I understood their Exquisite Corpse piece because of each artist's strong aesthetic and conceptual input. I read the phone conversation/artist's statement that was meant to be displayed with Lane Coulter and Jim Cotter's collaborative cement bowl and carved wooden spoon set, and I laughed out loud, clear about the honesty of their collaborative friendship and work habits. I am intrigued with Valerie Mitchell and Sandra Enterline's series of rings, each ring physically the work of one artist, but collaborative as a series, thoughtful and well developed. Enterline's two ring set with hollowed out magnets to set a diamond is conceptually astute and complex, spare and elegant.

I applaud the work of these and other successful collaborations and hope that the artists will continue such explorations. In the essay in the exhibition's catalog, Bruce Pepich writes that "Collaboration requires risk taking". The risk is, essentially, that the whole might be less than the sum of the parts. Several collaborations reveal this problem. One might suggest judicious editing by some of the artists themselves.

This article however, is intended to be less a review of the work in the exhibition than it is about the exhibition as a whole. It is unfortunate that the first venue of this traveling exhibition (and for "Crossing Boundaries" as well) is a cramped and inappropriate commercial gallery space. Both exhibitions deserve an expansive, well lit space; indeed, each piece in each show deserves such. Instead we were offered a confusing spatial arrangement that included jewelry from Mann's regular Gallery I/O collection. I wonder how different my impressions would be had the show taken place in that spare space that I yearned for. What I hope to point out is the importance of the entire scenario.

The exhibition was accompanied by a catalog of the show produced by the Wustum Museum with corporate sponsorship. The catalog documents the exhibition well, with a black and white photograph of each piece, a resume of the artists involved, artists' statements that talk about their work, the collaborative process, or the singular artist's own work. There is a dense essay by Wustum Museum Director Bruce Pepich that does little to really enlighten. He writes about each piece with descriptions of the artist's intentions that seem somewhat inflated. As I looked at some of the objects and read the artist's statements and read Mr. Pepich's comments, I wondered how did he infer all of that. I asked Mr. Pepich about this and he told me that he had seen only the collaborative pieces, and not the accompanying pieces made by each artist. And so, unfortunately, the essay concerns only half of the exhibition. The admirable intent of the curators in this show is to compare and contrast the results of the collaborative process. And if one has nothing to compare the results to, one is just commenting on a singular piece that, in some cases, has little to do with collaboration.

One last point: there was a statement that appears on what would usually be considered a price list that was readily available throughout the gallery. It said:

"THE FOLLOVINC PIECES ARE NOT FOR SALE. THE ARTISTS HAVE GENEROUSLY DONATED THEIR PIECES TO THE PERMANENT COLLECTION OF THE WUSTUM MUSEUM IN RACINE, WISCONSIN."

Because I know many of the artists involved, I am aware that not everyone was happy with this arrangement. The problem is that the concept of donating the entire show to the Wustum Museum was presented to the artists after they had created their work. This is purely conjecture, but let me ask: if the artists involved had known that their work would be donated before making their pieces, would their work have been the same? Would we be seeing a show with a heavy emphasis on found objects, alternative (cheap) materials, time saving techniques? Or, on the other hand, perhaps the artists would take their charge with more seriousness, knowing that the work will be part of a permanent collection, honored by their work's inclusion in such an important show. Perhaps they would be less experimental, take fewer risks, unwilling to show unresolved work. The point is that it would probably make a difference.

I'm glad there are artists who donate work to help to build museum collections, to help educate the public about what we as metalsmiths do, to further our field, and to keep the collective consciousness of metalsmithing alive and thriving. I'm glad there are people like Ebendorf and Mann who have a conversation of what ifs that ends up as a show that makes people think, that will reside in museums that are willing to show engaging work. In spite of some problematic aspects of "Double Vision", it is a stimulating exhibition with a challenging topic that will continue to intrigue adventurous artists.

Deb Stoner is a metalsmith who resides in Portland, Oregon.

Catalog available from the Wustum Museum

Double Vision, exhibition monograph, statement by curators Robert Ebendorf and Thomas Mann, published by the Charles A. Wustum Museum of Fine Arts, 1995.

John Prip: Medal for Excellence in Craft Award and Exhibition

Society of Arts and Crafts

Boston, MA

May 6 - June 25, 1995

by Jane Port

It would be easy for anyone to wander through this exhibit spellbound by the gleam of metal, the variety of sensuous forms and surfaces, and the quick wit of metalsmith John Prip's playful and reverent relationship to his materials. Contrasts abound in this retrospective exhibit that covers over 45 years and numbers near 150 objects. We marvel at the absolute technical assurance of the raised hollowware yet we are charmed by the tenderness of simple white butcher's string binding a stone found on the beach. Versatility and a searching spirit characterize the story of Prip's career.

Born in New York in 1922 to an American mother and Danish father, John Prip is a fourth generation metalsmith. Returning with his family to Denmark at age eleven, he entered a traditional five-year apprenticeship program in silversmithing at fifteen. Afterward he worked for several years for various Scandinavian firms as a designer craftsman. These traditional skills earned Prip his first academic position and in 1948 he returned to the United States to help re-establish traditional silversmithing skills at the School for American Craftsmen. During the same period, Prip co-founded Shop One to provide a retail outlet for the studio artist. Working in the industrial field during the 1950s, he updated the design aesthetic of the flatware and hollowware produced by the Reed and Barton Company of Taunton, Massachusetts. Beginning in the 1960s at the Rhode Island School of Design he managed to break new ground and develop programs in the emerging studio art field. Artist, teacher, entrepreneur, industrial designer, John Prip's accomplishments include an innovative and influential body of work.

The two-room gallery upstairs at the Society's Newbury Street location offers just enough space for the objects to be arranged attractively without seeming crowded. Vitrines are situated at comfortable viewing levels with labels in clear view The pieces range in time from 1950 to winter, 1995. Placed about the rooms according to form and function more than chronology are silver hollowware and flatware forms, jewelry, boxes, sculpture of various metals, a sketch book, drawings, and paper maquettes. Stone, bone, semiprecious stones, shells, gourds, and paper, alone and in combination, are placed on equal terms with metal. Prip's repertoire of processes is long and open-ended.

The bay windows and fireplace in the gallery, reminders of the rooms' former life as a domestic interior, work well with these objects. Prip's altered stones and postcards line the fireplace mantle as if they were at home. A round black electric plug and wire are carefully and precisely connected to a loaf-sized rough-textured oval stone with a machined fitting. Perhaps referring to utterly ineffective couplings or technology's problematic relationship to nature, the subject includes the pristine beauty of the oval stone paired with the respectful though insistent alteration by the artist. A black and white postcard of Marilyn Monroe is covered with a white paper grid of punched holes achieving a kind of witty short cut to the multiple views of the image made by Andy Warhol.

The technical precision and appreciation of essential natural form seen in the altered stones is apparent in the silver tea and coffee pots and flatware from the 1950s in the center of this room. Prip's raised Onion Teapot (1952) exemplifies the clean lines of mid-century Scandinavian design. (Happily, it has been purchased from the exhibition by a donor for the Boston Museum of Fine Arts). Prip learned the technique of wrapping rattan to shield the heat conducting handles for a number of his teapots. The sleek Diamond Coffee Service and Lark Flatware (1957) made as Prototypes for production by Reed and Barton Company are included in this display case. Prip's ability to hand raise a prototype with an understanding of how it would be put into production on the factory floor was a rare skill in America.

His return to teaching in the 1960s brought an opportunity for new investigation in form, process, and materials. The elegant raised copper spiculums, as wide as two outstretched arms were first made in the 1960s, and returned to in the 1990s. They hover rhythmically one above the other at the entrance to the exhibition creating what seem to be horizon lines above a beach of the small, smooth stones that Prip loves to collect from along the New England seacoast. This first impression of looking out toward the sea involves a calm feeling of balance and equilibrium experienced in Prip's work in general. It also suggests the importance of the sea and its inhabitants in his oeurvre such as in the two animated silver and gold crabs pins captured in one of the jewelry cases. These works are of human, even intimate, scale and beg to be handled and enjoyed. Whether their function is practical or imaginative, Prip's objects engage our attention on an elemental human level that returns us to our common origins and impulses.

A thirty-minute videotaped interview with the artist offers an introduction to the man and his work to visitors of the exhibition. Prip's lucid and disarmingly modest and direct discussion of his life and work offers a broad view of the role of the artist in the third quarter of the twentieth century and of his own particular multi-faceted role. Copies of the tape are available from the Society for $20.00 and postage.

Although he is a disciplined worker who puts in regular hours every day, Prip describes his work habits as actively anti-productive. He believes the only good reason to make something is because it appeals to the maker at that rime. Objects may be started, put down and finished later or the same form such as the spiculum, made again years later. His curiosity prompts him to dream of making something never seen before in history.

Boxes and containers of all kinds have been born in Prip's studio since the form arose as a less limiting vehicle for expression in the 1960s and loosened the grip of traditional functional vessel forms. The enigmatic silver and gold Fish Box with Lid (1965-66) gives us the whole creature as container with adorned silver lid. The humorous Willy's Bone (1969) and Finger Box (1970) are containers made in the shape of human body parts. Leaking Box No.2 (1970) plays with the illusion of liquid metal. Later containers like the monumental Steel Container with Lid (1989), a slim rectangular sheath or the bronze Sumo Jar (1985), rotund in shape, carry an aura of ritual and tradition. Most recently, the artist has collected small, oval stones from the seashore. At first he used sandblasting techniques to radically alter their texture, creating script-like raised patterns on some, face-like designs in others. Later, he sandblasted a cavity, polished the stone and added his own stamped silver lids decorated with abstract patterns and symbols. Collecting and altering a natural product for domestic or ritual use is a timeless human activity. Following that impulse, the exquisite union of nature and culture in these small objects proves extremely satisfying.

The Boston Society of Arts and Crafts was the major force behind the arts and crafts movement in New England in the early twentieth century. Its influence was felt across America and medalists from its prominent metal guild often enjoyed national recognition. None could have been a more deserving recipient than John Prip.

Jane Port is a writer and a decorative arts historian. She lives in Wellesly, MA.

Revealing Elements Work by Three Metal Artists: Denise Barr, Sara Sepherd, Joana Kao curated by Victoria Haven

MIA Gallery, Seattle, WA

March 2 - April 2, 1995

by Dana Standish

Poignancy is the order of the day in this show by three young women at the MIA Gallery Most people have an almost allergic reaction to the word poignant. Just the mere sound of it, an elongated whine of a word that you have to draw out through your nose as though it were on the end of a thread, makes people run for cover. Poignant conjures up a cloying sentimentality, or that most dreaded of all epithets, a female sensibility. But the root of the word is from the French poindre,"to pierce," and many of the works in this show are heart-piercing indeed in their comments on love and loss, the power and limitations of faith, and our universal desire, as humans, for belongingness. This is a show rife with female power and female sensibility in its most poignant and energetic sense.

Not all of the profound significance of each piece of Sara Shepherd's work is readily accessible to the viewer. The successful pieces are the ones that can convey this universal particular, a recognition on the part of the viewer. But sometimes the exact meaning of the artist's vision may be lost on the viewer and the artist must resort to obscure titles in an effort to clarify the meaning of the image. Yet, this can often compromise success. Such is the fate of Shepherd's Ego Structure, a work that smacks of a BFA Thesis Show. Because of the imagery one can guess at the work's ponderous importance, but I like to be hit over the head with messages, myself. Shepherd is more on target with S Loves L: Love Song, a piece which shows the subtle power of which she is obviously capable. A chain-mail choker fits snugly around the neck of the female form on which it's displayed. The chainmail seems just right - a symbol of painstakingly-made bondage and protection. From the choker hangs an empty, silver birdcage with an open door; whatever love was there has surely flown. The cage hangs from a gold wedding band, inscribed "S Loves L". This piece beautifully combines message with imagery. Its emptiness is palpable, due to the fullness of the artist's vision.

Denise Barr uses Catholic iconography to make her statements. She combines mass-produced enamelled images of the Virgin Mary and the Baby Jesus with found and/or constructed objects on which she often stamps messages from popular culture or of her own devising. An example is a pair of earrings with a central icon of the Virgin Mary holding the Christ Child, attended by angels. From the bottom hangs a cross and from that a small star. Barr has stamped "When You Wish Upon a Star," on one earring, and "Your Dreams Come True" on the other. In this case she would do better to forget about the jewelry side of things and concentrate on developing her imagery, which she has sacrificed in the name of earrings, not always a good choice. There are several Frida Kahlo inspired pieces that work well as jewelry. A large image of Kahlo's face, bezel set under a lens with all sorts of milagros inside: hair, a tiny silver bird, flower petals, is surrounded by the stamped words "A Duras Penas; Through Hard Pain"' Below Kahlo's eye is a bezel set taxidermist's eye staring with the same intensity. Below this hangs a cross of black. Other works borrow so heavily from Catholic iconography as to be almost indistinguishable from Church objects. When Barr combines this imagery with her own vision and message her works are most effective.

Joana Kao also uses the narrative structure in her works to varying degrees of success. Culturally Challenged is a silver half-sphere with a small propeller on the front. On a stage inside the sphere stands a crowd of people of different colors. When you spin the propeller, the platform spins to the bottom and a new crowd of people appears from the underside of the stage. In each case there is one person who is a different color from the rest. It is a simple yet eloquent visual representation of the person who is different, yet essentially the same as those around him/her. In her artist's statement, Kao says that she tries to communicate her feelings of being Chinese-American, and the frustration she feels when people want her to declare that she is "one or the other". In this piece it seems that Kao sacrifices some of the power of the image by hanging the central statement on a somewhat ordinary (though handmade) chain. I Never Liked Musical Chairs is a necklace-bracelet combination with a lone person left out, hanging at the end of the necklace's chain. From the front of the necklace hang handmade chairs of different styles; all are stamped "Reserved" or "Taken". Again Kao explores the pain of the outsider, this time in a more personal basis than in Culturally Challenged. I have the same concerns about the unexciting nature of the chain in this piece, but here her vision seems to be clearer than in the other work.

The MIA Gallery has given these young women a forum, a place where they can be heard, for surely artwork is the voice of the visual artist. Some of the works in this show are the early attempts at speech; some of them whisper their power, while some shout incoherently. Often the work speaks beautifully, and it is up to us to listen.

Dana Standish is a metalsmith living in Seattle, WA.

Makers & Shakers

Mario Villa Gallery

New Orleans, LA

April 1 - 31, 1995

Wheeler Gallery

Deer Isle, ME

June 7 - July 25, 1995

Edith Lambert Gallery

Santa Fe, NM

August 3 - September 21, 1995

Margo Jacobsen Gallery

Portland, OR

September 30 - October 30, 1995

by Julie Flanigan

In a city alive with sights and sounds such as New Orleans, the title "Makers & Shakers" brings many images to mind: people swaying to the rhythms at Jazzfest, colorful Mardi Gras beads flying through the air in the French Quarter, dice rattling in the palm of a gambler at the new casino. The exhibition by this name at Mario Villa Gallery, opening in conjunction with SNAG 1995, did not disappoint New Orleans viewers.

Rosanne Raab Associates invited contemporary metalsmiths to exhibit their work in "Makers & Shakers" and instructed them to research the shaker. I found shaker in the Random House dictionary defined as "n. 1. a person or thing that shakes. 2. a container with holes in the top, used for holding and sprinkling sugar, salt, etc." Armed with similar knowledge, the thirty participating metalsmiths produced work for the show which is varied in style, materials, and intent. Ranging from traditional shakers for salt & pepper and cinnamon to a large aluminum rattle in all the colors of Mardi Gras, each design combined the spirit of its maker and his or her interpretation of the shaker.

Unlike most people who saw the show in the back gallery at Mario Villa, I was fortunate also to be able to hear the show. As I explored the gallery before the official opening, the work had arrived and had been unpacked, but it was not yet displayed in glass cases. Two things about this situation were very exciting. First was the opportunity to identify the makers of the unlabeled work. Using the invitation as a cue card combined with my knowledge of these artists, labeling each piece was a challenge. The second surprise was the added pleasure of sound as I picked up several of the shakers to hear their music. The noise, the feel of the piece in the hand, and the ability to see and feel the full three dimensionality of the work made my first trip to the gallery very worthwhile.

On my next visit, I found the work properly displayed in cases, and was provided with an exhibit list which identified each piece by title and designer. Many of the artists took advantage of the high-spirited show title and gave their designs descriptive and intriguing names. Marcia MacDonald's neckpiece Shaken Not Stirred, contains a caged silver spoon. Sue Amendolara's Jungle Song rainstick rattle is a soft three dimensional column of silver delicately wrapped in a leaf, vine. Arlene Fisch created Fish Are Quiet Shakers, a metal sphere with a small opening on top that has fish bouncing from springs above it. And with a predictably off-beat sense of humor is Fred Woell's I Spy Alert Mace Rattle Spy-Scope, a tall pillar of telescoping layers of brass and copper. On Woell's scope shaker arc photoetched portraits: a woman and a group of gentlemen; three hands with outstretched fingers point in three different directions; and a 1166 penny. Commercial keys hanging from the scope's rim, twisted out of working shape and engraved with "It is unlawful to duplicate this key," provide the rattle for this shaker.

Many of the pieces have attachments, parts connected to the work with mechanisms that allow movement. The viewer imagines that the parts will move if the piece is agitated and develops a desire to hear the instrument's music. A piece like ROY's Greek Rhythm, wristform tambourine, for example, must be worn and shaken, allowing the domed bottle cap hemispheres to rattle against their temple cage.

Several of the pieces in the show are objects which could fit into the category of noise makers. Tom Loria's Wrist Whirler, a heavily textured copper form, looks like a branch covered with woodpecker holes. Berry-like beads rest in the holes where the musician holds the whirler; wavy metal charms dangle from jump rings providing the rattle when the wrist kicks into action.

The spirit of Douglas Harling's shaker, The Ghost Outside/The Devil Within, created from a branch, comes from the three frail fingers reaching out from a skeletal arm. Painted in vibrant colors to ward off evil spirits, charms dangle from the appendages, clinking together as the shaker is held.

Boris Bally's Armform for Tyl Eulenspiegel is a thick gold plated brass bangle with three pod shaped appendages which orbit around the wearer's wrist. Inside the shiny silver pods, which have pierced geometric patterns, hematite and black onyx balls rattle as the arm moves. In Bally's statement, we learn the inspiration behind his shaker design and the piece seems to come to life. As Bally explains, "Tyl Eulenspiegel was a famed European jester with bells on his cap. The rattle's playful sound comes from its three pods which are filled with semiprecious stone beads. Mysterious things happen when the wearer sings, dances and rattles his armform rhythmically."

Robin Kraft used the the human figure to make l poignant statement in Ghosts. The simplified person, fabricated from silver, is a flat structure appearing lifeless with a hollowed our core. From the empty interior a shadowy figure, mimicking the outer form, springs a ball on the end of a stretched coil. For Kraft this shaker references the ghost of cancer, rattling around inside the body like a time bomb waiting for detonation. The eerie quality the artist intended is easily felt by the viewer who longs to know what the figure holds in its negative space.

I found the most elegant piece in "Makers & Shakers" to be Joy Raskin's Flex/Shake, a delicately woven rattle with a very soft, private sound. The surface has an intricate texture, playing silver and brass together with the look of a tightly woven metal basket. The form has the shape of a small maraca or a religious implement. The 7½" rattle has a comfortable, mystical feel when cradled in the shaker's hand.

The reasons for delicate metalwork to be displayed under the protective cover of glass are obvious. Nonetheless, the works in "Makers & Shakers" call out to be handled. Viewers cannot understand the cleverness of many of the shakers when exploring them only with their eyes as movement and sound are crucial elements of the artist's intent. It would be educational and more enjoyable for viewers if there were a forum for such work to be displayed openly and interactively.

Julie Flanigan is a metalsmith working in Baltimore and teaching at Maryland Institute, College of Art.

You assume all responsibility and risk for the use of the safety resources available on or through this web page. The International Gem Society LLC does not assume any liability for the materials, information and opinions provided on, or available through, this web page. No advice or information provided by this website shall create any warranty. Reliance on such advice, information or the content of this web page is solely at your own risk, including without limitation any safety guidelines, resources or precautions, or any other information related to safety that may be available on or through this web page. The International Gem Society LLC disclaims any liability for injury, death or damages resulting from the use thereof.

Related Articles

Pinakothek of the Modern

Ornamentum Gallery: A Jewel in Constant Transition

Metalsmith ’88 Fall: Exhibition Reviews

The Life Works of Carl Jennings

The All-In-One Jewelry Making Solution At Your Fingertips

When you join the Ganoksin community, you get the tools you need to take your work to the next level.

Trusted Jewelry Making Information & Techniques

Sign up to receive the latest articles, techniques, and inspirations with our free newsletter.