Metalsmith ’85 Spring: Exhibition Reviews

50 Minute Read

This article showcases the various exhibitions in the form of collected exhibition reviews published in the 1985 Spring issue of the Metalsmith Magazine.

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

Peter Chamberlain: Exhibition of Unmetal

Hartmann Center Gallery, Bradley University, Peoria, IL

Fall, 1984

by Karl Moehl

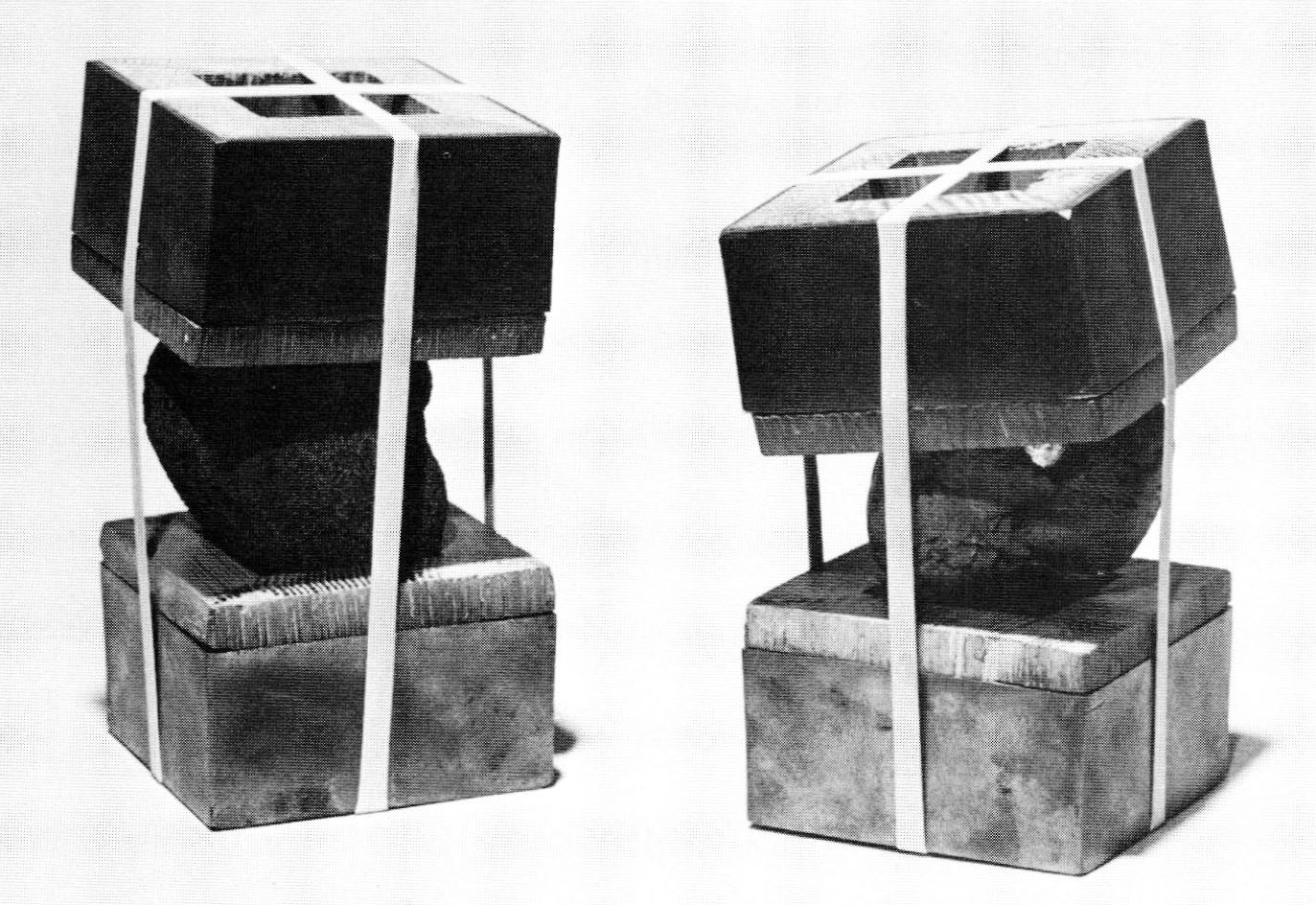

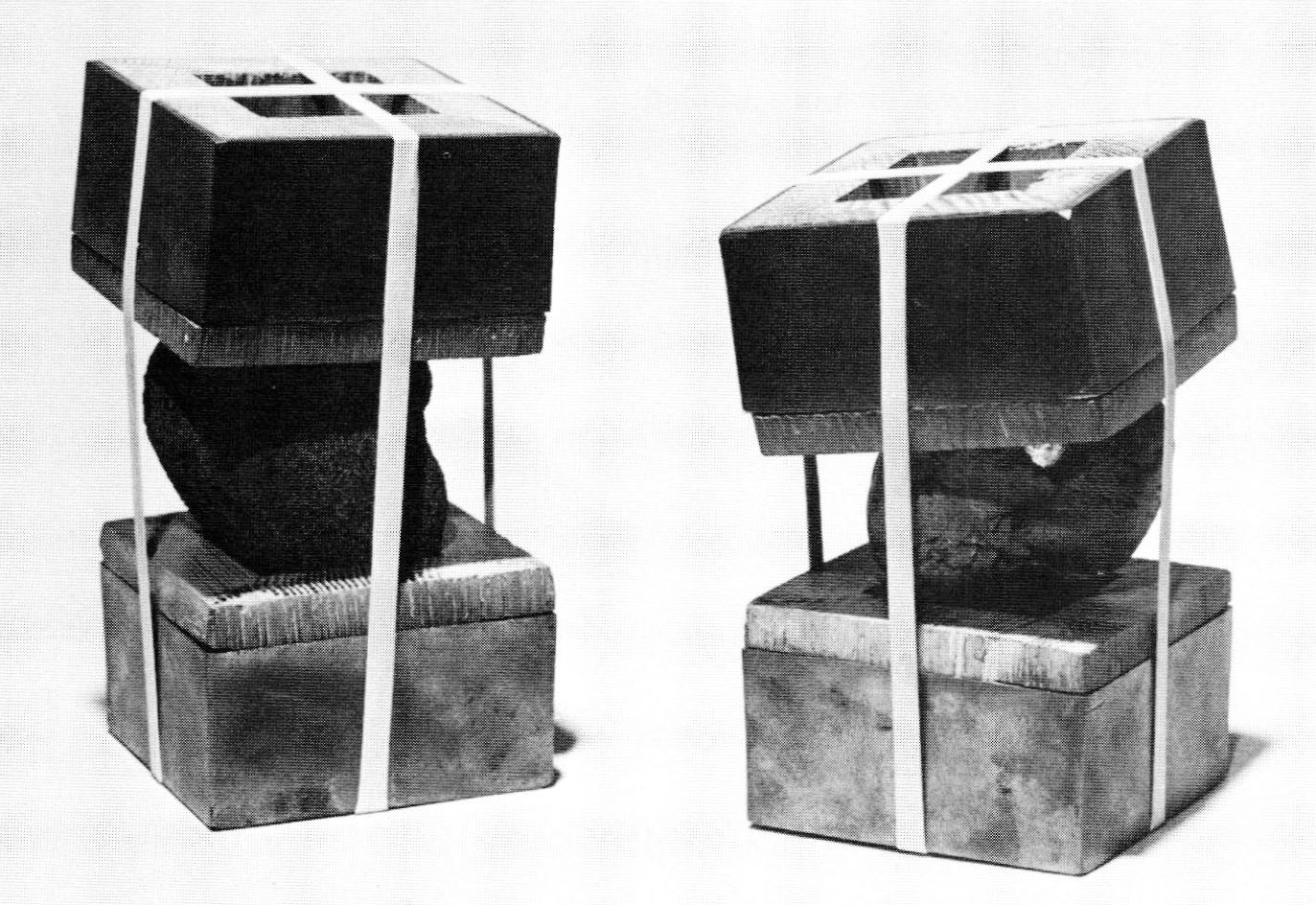

Peter Chamberlain is the self-appointed maverick of the art metals world. It is therefore not surprising when he tells us how the works that comprise this show were assembled. He says he rummaged about the studio and took bits and pieces he found — crude pre-art and raw refuse — and utilized them in an "unmetal" manner. The resulting show featured a series of clever transformations involving rods of metal, tubes of screen wire, circular saw discs and metal miscellany. Cotton balls, styrofoam cones, rubber bands and other nonmetal elements intermix as well. Even an outsider can appreciate this gentle spoof aimed at the "academic metal mania scene" that the artist mentions in his posted statement.

Taken out of this satirical context, Chamberlain's Bradley improvisations can be seen as a sincere albeit modest attempt to establish some foothold in the postmodernist morass. As with others in this predicament, the artist betimes has reverted to the primitive and essential, in this case eoliths or magic stones, the original found art objects. We see the stones "under pressure" (sandwiched between wood blocks), "in Siberia" (fenced in by wires and nails) and strapped in a "traveling kit" (along with sunglasses and a cuttle bone).

Otherwise, the titles clue us in to different intimations and intentions of the artist concerning "the blast." There is a photograph of large nails stuck in the sand "witnessing the blast," while below it stand the nails themselves compartmentalized in a clear plastic box, described as "glowing from the blast," After the Blast is a symmetrical assemblage that could be taken as a space-age Noah's ark, accommodating the miniature kangaroos that climb its masts, or it may be seen as one of those sci-fi mutants we have learned to recognize.

Seen cold, without taking notice of the titles, or the obligatory artist's statement, or even without knowledge of the artist's background, the work has charm and ingenuity. The gallery was given the look of an eccentric toy store. But it also was a bit wan, and perhaps dispiriting. Seen with the full freight of the erudite meaning suggested by the titles and statement, the work seemed too delicate, too incidental and casual to bear it. Rather in light of the suggested incendiary concerns, the show seemed to be the musings of an intelligent mind and clever hands which, without intensity, fiddled before the flames. True, the artist may have avoided mindless preoccupation with technique itself, but the freedom gained hasn't yet afforded a compelling resolution of much else.

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

Metals Invitational

November 18, 1984 - January 6, 1985

New Harmony Gallery of Contemporary Art, New Harmony, Indiana

Curated by Lynda LaRoche

by Teresa Callahan

The fashion industry of the 80s has absorbed many of our avenues of aesthetic expression, therefore blurring original intent. Just as fashion killed New Wave music, metalsmithing has become an assuredly confused relative, overlapping with the jewelry industry. The visuals remain, but the original statements are obscured. Postmodern expression in all media seems to be in transition.

This exhibition typified that crossover. It featured very little "clean" metal, but the objects were so perfectly executed that one was dazzled. Function follows fashion in most of these crisply processed pieces. Unlike the trend in the 70s, there were no attempts to elevate objects to art via price tags, titles or conceptual gimmickry. The 80s see an aspiration to fashion through abundant combinations of contrasting materials packaged with a flawless finish, shots of color, moderate pricing, reasonable size and a justifiable, decidedly nonromantic format. These concerns were demonstrated here by production jewelers, witty metalsmiths and educators. Much of the work was so precisely crafted that it appeared icy — the only warmth lent by color. The most refreshing titanium was shown by Lin Stanionis (Oxford, OH), who offered pistachio and citrine rather than the exhausted blues, purples and magentas. While this exhibit contained the work of 10 metalsmiths, two stood out for their different versions of hybridism.

David Tisdale (NY, NY), as always, showed tasteful, thoroughly contemporary and technologically advanced work. His Disc Bracelet wore a rich, full teal blue that outshone any of the niobium/titanium genre. His chosen material, anodized aluminum, is in itself, a metaphor of the times. He is an exemplary metalsmith of contemporary attitude, stance and style. Pat Flynn (New Paltz, NY) exhibited sensitive pieces using texture and contrast combined with an extremely light, skillful touch. Flynn featured origamilike wrapping and bundling with a quiet evidence of the human hand. There is a primitive-modern dichotomy here, demonstrating a certain amount of control, but allowing glimpses of emotion. Flynn's work lives with that human input that endures and assures a greater variety within the realm of visual experience — a legacy worth preserving, even in the 1980s.

A black-and-white catalog of the show is available from New Harmony Gallery of Contemporary Art, Owen Block/Main Street, New Harmony, IN 47631 .

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

Carol Kumata, Beth Potter Rizo-Patron

Elaine Potter Gallery, San Francisco

October 16 - November 17, 1984

by Florence Resnikoff

As the owner of the Contemporary Artisans Gallery for many years, Elaine Potter contributed greatly to the art scene of Northern California by presenting a showcase for California crafts. Recently, she has moved her gallery to the newly developed San Francisco gallery area, changed the name to the Elaine Potter Gallery and continues to be innovative in her exhibitions.

Last fall she invited 40 jewelry designers to submit their most inventive sculptural earrings for a show entitled "The Artful Ear" An impressive exhibit resulted. During this period the gallery also featured work by Carol Kumata and Beth Potter Rizo-Patron. Both artists come from a metalsmithing background, which is obvious from their mastery of materials: both are moving beyond technique and presenting sculpture rather than "object."

Kumata uses primarily the format of the box, about one-foot cubed, in which she combines metal with wood, plastics and wire. The size functions as an intimate arena where the viewer must peer into tops or openings in order to see the contents. This works well in one respect, but in some of the work, such as Sun & Moon, the small size creates a congestion of images, further complicated by a heavy wooden carved top that seems out of scale.

Meltdown, an acrylic model of a transparent brick house with flames coming through the floor was one of the strong statements of the exhibition, as was Mixed Metaphor (has anyone looked up the definition of metaphor lately?) In its strong spatial relationships and minimal images this sculpture conveyed a strength missing in the more complex pieces.

Kumata's earlier work, sometimes described as being oriental in feeling, was replaced in this exhibition by work with more complex imagery and greater involvement with surface patinas, painting of metal and cutting of sheet, which she springs into dimensional forms. Her handling of materials is elegant.

Beth Potter Rizo-Patron's work is larger in scale than Kumata's and the immediate impression was a sense of awe at the highly technical construction. The work is machine oriented, highly finished and architechtonic. Rizo Patron works equally well with metals, plastics and fibers. One piece which I liked was Lying In State, a beautifully resolved structure of a bronze casket within a glass (or acrylic) form, using cop, per, brass and aluminum with equal panache. Purple handles enabled royal pall bearers to carry off the beautifully polished and machined sculpture. Tales of the Artic Winds, a three-foot disc of white acrylic with a mirror reflecting a complex structure above, all very technical and highly polished was a strong statement but suffered from its complexity.

One of Rizo-Patron's strongest works, but for me a bit overpowering, was Common Denominator, a large structure incorporating seven units, each of which was made up of eight separate elements: half domes filled with tiny plastic discs attached to squares, attached to tubes, attached to bars, attached to cast iron forms. My feeling was that a single one of the seven units would have served as the basis for a handsome structure I thought one of the most appealing sculptures was Reaping What You Sow, a vertical structure made up of horizontal bundles of wires tied with wire tipped with colored plastic. This was mounted on a tubular form attached to a rectangular base. The most controversial piece in the show, according to the gallery staff, was Of Men & Their Monuments. This was an impressive work about tour feet square. Horizontally oriented to be viewed as a commemorative. It was created with great mastery, using both fabricated and cast bronze elements of men and a statement by Dag Hammerskjold. The many images, some legible, others not, created a powerful memorial.

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

Metals

Dawson Gallery, Rochester, NY

September 7 29, 1984

by Deborah Norton

In this exhibition the work of Kenneth Louie, Christopher Ellison and Carolyn Morris Bach can be assigned to known metalsmithing categories that are easy to assess. However, the innovative work of Debra Chase, by refusing to fall within the confines of identifiable trends, presents a welcomed challenge to the reviewer.

For this show Chase created several life-sized forms, akin to theater costumes, out of commercial annodized aluminum screening. Though obviously related to clothing, these nonwearable objects suspended from the gallery's ceiling, were clearly not in the trompe l'oeil tradition. And although nonfunctional, they did not seem to lit comfortably in the domain of sculpture.

In Three Sisters, Chase uses the basic kimono shape as a point of departure. The arcing, rhythmic curves, accentuated by zig-zag strips of solid aluminum that outline each of the three pieces in the series add vitality to her forms. Randomly scattered on the kimono are numerous "brooches," done in a style reminiscent of the machined look that has become synonymous with RIT, Chase's alma mater. These simplistic brooches consist of a square of screening, sometimes backed by a solid bronze-toned square, ornamented with a single piece of transparent plastic tubing in peach or light green. With these jewelry forms, Chase seems to be good naturedly mimicking the fashion and conceptual art jewelry produced by many of her former classmates. These brooches and the small bronze-colored triangles that also dot the garment, combine to push the piece toward the realm of pattern and decoration. However, attempting to place her work within this category, or within the category of representation and narrative (because these bodiless garments seem to have a story to tell), does disservice to the originality of Chase's artistic conception.

Kenneth Louie, also a recent RIT graduate, exhibited small "sculptures" that were actually brooches on display stands. Predictably, he works in the machined style one has come to expect from an alumnus of this school. The use of a sculptural format to display a piece of jewelry when it is not being worn is a noble concept. However, while the square-within-a-square-within-a-square motif of Louie's jewelry-display-stand sculptures successfully integrates the two elements — to the degree that it is difficult to tell where the brooch ends and the stand begins the sculpture itself is visually weak. The overabundance of so many strong lines in such a small space makes for confusion and lack of direction. There is no sense of what the sculptor is trying to do or say.

Surprisingly, the brooches themselves, when lifted off the stands, are quite successful. In his finest piece Flying, Louie has created an open square frame on which float several well-integrated forms. He has effectively added depth to the piece in various ways. by raising the top leg of the square into an asymmetrical arch; by curling up the corner of the clear acrylic sheet that covers a flat piece of red paper; and by thrusting a red, winged form beyond the boundaries of the square. In a refreshing change of pace, he has avoided the ubiquitous titanium, tantalum and niobium as a means of adding color and instead has relied on paint and colored paper. In place of a commercial pin stem, he has fabricated a stick pin that runs diagonally through the piece. In making the finding an integral part of the piece, Louie is exploring a potentially fruitful area of metalsmithing that is too often ignored. The flag flying at the head of the stick pin and the playful curl of the acrylic add a welcomed touch of lightness to his otherwise serious, intellectual approach.

The third RIT graduate in the show Christopher Ellison, seems to be a metalsmith in search of a direction. Within the confines of this exhibition he has chosen to display 1950s-style tables, functional vessels, an oriental-style nonfunctional vessel and sculpture. Although bits and pieces of several of his mild steel and copper creations are intriguing — a nice use of pale green patination here, an interesting form there — he has not explored or developed any one idea in adequate depth. When and if he were to accomplish this, there appears to be the potential for interesting results.

I come finally to Carolyn Morris Bach's elegant cosmetic brushes, devoid of deep, intellectual content or highly innovative concepts. By ignoring the latest metalsmithing fads, this RISD graduate makes a strong case for the traditional craft concept of creating beautiful, functional objects. In the best of Bach's silver and copper brushes she has sensitively designed the handles to reinforce, rather than ignore, their inherent conical form. She does this by embellishing the lightly textured surface with widely spaced parallel bands and by finishing the tip of the handle with tiny telescoping tubes. While contemporary in design, these brushes have a timeless quality that is missing in much of today's metalwork.

By juxtaposing innovative and traditional work, this exhibition demonstrates that it is the quality of design and craftsmanship, coupled with the sincerity of the artistic conception, that produces the best results.

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

Helen Shirk

The Hand and the Spirit Crafts Gallery, Scottsdale, Arizona

October - December, 1984

by Betsy Douglas

For more than a decade Helen Shirk has been acclaimed internationally, both for her holloware and for her jewelry of titanium and precious metals. In her recent holloware she has taken a courageous new esthetic direction, which was evident in the 15 vessels featured in this show. For Shirk this series of patinated copper and bronze works represents an unprecedented exploration of new sculptural forms.

Outstanding among these new works was Vessel CV8B, a large boatlike patinated copper container constructed of four layers of sheet metal that fit inside one another and are riveted together Two interior layers are patinated in a smooth black finish and resemble a multipointed abstraction of a leaf silhouetted against a softly colored layer of blue-green copper. The background layer of metal has a speckled black, blue-green and copper pattern. The overall effect of these superimposed layers is the creation of an aggressive sculptural form that suggests the dynamic release of some internal energy springing out and slicing into space. This soaring vessel is remarkably lightweight for its size.

Vessel CV10B suggests jagged pointed leaves of an exotic plant, coiled together. From an inner core, the layers of metal unfold and thrust out in opposing directions. The outside layer is a smoothly finished gray black. The interior layer is a tiger-striped pattern of turquoise, copper, rust brown and blue black. The total effect is a sophisticated integration of form and sensitive treatment of the patinated surface coloration.

In describing her work Shirk states: "This work reflects influences absorbed from living in an essentially desert environment. It is the alliance of seductive color and pattern with aggressive form, a partnership so often found in the flora of an arid landscape. The forms evolve through an additive process: the buildup of layers which penetrate or enclose space, the injection of color which creates evocative surfaces, the development of a scale in the piece which makes possible a powerful gestural statement."

These recent works also demonstrate Shirk's highly creative use of patinated surface coloration, which is the outgrowth of exploration conducted during a sabbatical leave lo England in 1983. At that time she talked with Richard Hughes and Michael Rowe, authors of The Coloring, Bronzing and Patination of Metals. She returned to San Diego State University, where she is a professor of metals, and continued investigating patination processes. Shirk shared this technical information about surface coloration at the Great West Metals Symposium at Flagstaff, Arizona in February 1984. An accompanying show of her work gave the public the first opportunity to view her new direction.

Shirk's visually dramatic vessels have a characteristic elegance. Working on a larger scale and in a freer manner than she has in the past, she has made an aggressive esthetic statement that does not rest on the notable success of her earlier work. Instead, her new holloware dramatically evidences Shirk's ability to take creative risks in the continuing development of her art. Also to be congratulated for encouraging this courageous effort are the gallery owners, Star Sacks and Joanne Rapp, who realize that only through the cooperation of progressive artists and dealers can we expect the field of contemporary metalworking to continue its evolution as an art form.

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

Contemporary Jewellery: The Americas, Australia, Europe and Japan

National Museum of Modern Art, Kyoto, Japan

August - December, 1984

by Florence Resnikoff

The first half of the 1980s has been kind to jewelry designers Museums in many parts of the world have been exhibiting international as well as regional shows. Catalogs from these shows have demonstrated a certain internationalization of work, and yet there are still many surprises. While wide-ranging technical mastery is evident, what has changed is the intention of the artist.

Two museums have presented historical sections in their jewelry exhibitions. By coincidence, both covered the same period. "Schmuck International 1900 - 1980″ opened in Vienna in June of 1980. The historical section showed work borrowed from the Pforzheim Museum in Germany, the Kunstgewerbemuseum in Prague and the Osterreichisches Museum in Vienna. To put the contemporary work in perspective, the museum displayed work from the turn of the century, including that of Lalique, Gaillard, Ancor, Jensen and others from the Art Nouveau to Art Deco eras. The contemporary section exhibited work by 155 artists from Holland, Germany, England, Japan, the United States, Italy, Poland, Finland and Austria. This work, created in the mid to late 1970s, already exhibited the departure from precious metals and gems, apparent in the earlier format, and now seemed to reach for the art image. Technical mastery of other materials — plastic, fiber, ivory, steel and glass — helped produce the desired effect. There were few cast pieces, most having been fabricated. All were wearable. The black-and-white catalog devoted one 10 x 11" page to each artist.

The other exhibit was held in Spain, entitled "80 Anos de Joyeria y Orfebreria 1900-1980." Here, too, earlier jewelry designers, Lalique, Vever and others from Switzerland, France and Germany, plus a number of Spanish artists of that period, were presented. The contemporary Spanish jewelry designers showed some influence from both the Art Nouveau period and from traditional goldsmithing, but recent experimental work, which used both industrial and nonprecious materials, was also displayed.

In May of 1984, "Jewelry International" was exhibited at the American Craft Museum in New York City, including the work of 50 artists from 17 countries. The catalog pictures the work of 39 artists in black and white and nine in color.

Then August of 1984, "Contemporary Jewellery: The Americas, Australia, Europe and Japan," sponsored by the National Museum of Modern Art, opened in Kyoto, Japan. There was some confusion as to whether this was part of the above exhibition; it was not. The Japanese exhibit represented many more artists and more countries than any previous international survey. Of the 22 countries represented, and almost 500 exhibitors, the United States had the largest contingent, of which most were Society of North American Goldsmiths members. Sixty-two artists had also exhibited in "Schmuck International" and 27 had exhibited in "Jewelry International." From the personal travel of curator Shigeki Fukunaga to the professional packing and transporting of work to Japan, to the publishing of a smashing full-color catalog of every piece of work in the exhibition, the show was a major undertaking, with seeming disregard for expense. The beautifully photographed, large-format catalog is an important and valuable resource that should be in every metalsmith's library. (See Book Reviews for review of catalog.)

In Kyoto, the work was displayed in five glass-walled exhibition rooms plus a gallery with life-sized mannequins wearing body jewelry in rather startling arrangements. There was great diversity in the jewelry, ranging from unwearable to delightful to impressive to masterful to colorful to wonderful Internationally speaking, the work was strongly attuned to the art image — not the decorative — the tour-de-force, not the competent cliché. All metals, all materials, all forms conveyed a great feeling of fun in the creation.

Being an invited artist to the exhibition was a compelling reason for planning a first visit to Japan. Other than Japanese exhibitors I was able to identify only two other exhibitors at the reception: Hiroko Pijanowski and David Castle. Due to the international nature of the reception, I found the ambience rather sober. Many of the more than 600 people attending were dressed in dark business suits, with the women also seemingly dressed for a civic occasion rather than an art happening. The many speeches reinforced this impression. However, it was a wonderful experience to have gone to Japan and to have participated in this fine exhibition.

The catalog is available for 8,230 Yen, air mail (approximately $33.35) or 4,830 Yen, sea mail (approximately $19.57). To order a copy, write for a remittance form to: Miss Ayumi Kondou, Registrar, National Museum of Modern Art, Kyoto, Okazaki Park, Sakyoku, Kyoto, 606, Japan.

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

Komelia Hongja Okim

Montgomery College, Rockville, MD

September 1984

by Jack da Silva

Reflecting on the accomplishments of culture as expressions of human kind, development of the city represents a major example. When we conjure up a cityscape, silhouettes of tall, stark, massive buildings may come to mind. Lights mirrored in the panes of glass, technology's theater of progress. However, when similar visions are approached by an artist, such as Komelia Okim, other facets begin to emerge.

Recently returned from continued travel, research and teaching in Seoul, Korea, Komelia's love for the city, people and her art were clearly seen in this solo exhibition. Influenced by abstract qualities of the city, pieces, such as Story of Syo Kyo Ave. and Seoul Bridge, presented dynamic formed/constructed compositions that beckoned the viewer to become involved in the brightly colored activities seen through the "windows." The interaction of peoples energies generated in the joys of life seemed to shine from the very structure. Concepts of humanity and intuition forming the core, as in Tea Time, Special Outing and Ceremonial Outing, lent a richness and depth of purpose in these tea services and containers.

Also apparent is the importance of Okim's involvement with and love for the metal. Using the characteristics of the material as a means toward an end rather than denying them, the metal becomes important as the vehicle of her imaginary vistas. Several traditional Hangul (Korean) methods are found juxtaposed with exotic "high-tech" materials. Each material, alloy and technique contribute their own personality to the complex statements generated from Okim's multicultural experiences. Her vitality and directness toward life strongly expands her curiosity in the exploration of form, rather than limiting the search to the minimalist nonstatements/nonforms that seem to plague so much "art" today.

Komelia Okim's variety of work, from jewelry through holloware and sculpture, reflects the impact of the environment around her: the land, the city and especially the people.

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

Yeo-Ok Chang and Helene Safire

September 15-October 16, .1984

Plum Gallery, Kensington, MD

by Komelia Hongja Okim

This dual jewelry exhibition revealed similarities—both Safire and Chang have drawn their ideas from landscapes, one from urban, the other from nature, as well as contrasts—Chang's work reflects atmospheric landscapes of both Korea and the Mohawk Valley, NY, whereas, Safire's work depicts elements of the urban landscape from the fresh perspective of aerial photography.

Yeo-Ok Chang uses ebony, ivory and abalone in concert with gold, silver and mild steel to express color harmonies. Roller-printing, metal weaving and reticulation all provide surface embellishments. Of particular interest is her use of a traditional Korean metal technique in a contemporary approach, seen in her necklace and earrings entitled Golden Days. As the title suggests, these pieces were done with intricate gold, silver and copper wires, lavishly enriched by inlaying over the black background mild-steel. This technique is called Pomok-Saang Gaam, Pomok meaning fabric and Saang Gaam inlay. It is similar to Damascene, which has been used in many other countries, such as India, Japan and Spain. It differs in that rather than foils, threadlike fine silver wires are hammered into the finely chiseled steel surface.

Most of Chang's work is in low relief. Her involvement with the landscapes of Korea and the Eastern United States are clearly reflected in the composition and titles of her work, e.g., Silver Scape, Golden Sand, Snow-White, Mohawk Scene and Ebonyscape. Chang freely expresses her concepts with carefully decorated surface's and marriage of metals as well as inlaying manmade and natural materials. The technical execution of her work is flawless. Although many of her pieces employ geometric shapes and lines, they are softened by her incorporation of color, the subtle application of surface variations and organic materials. The end result is work that has warmth and sophistication and appears thoughtful but not labored.

Using similar concepts and impressions, Helene Safire has employed her creative and adventurous thought processes to interpreting aerial photographs of selected urban landscapes. She combines satin, high-gloss and etched surfaces with geometric shapes, punctuated by the use of different shades of green, blue and brown gems and the inlaying of cool enamel and epoxy resin. Her workmanship is clean, precise and meticulous in the use of lines and angles to achieve the subject matter.

The title of her pieces reflect many of her own life experiences, e.g., East Hampton, South Hampton and Bridge Hampton. The individual environment is so clearly depicted that one feels as though one were really seeing it from a sky-high vantage point. Particularly effective was Surreal Estates, in which Safire combined a reticulated surface (the pin) with imbedded, but removable, earring pairs in geometric shapes to form a total landscape. The Water's Fine is another example of her ability to wed elements of metals and gems, in this instance a satin-finished metal surface with a cool complimentary aquamarine cabochon to create the illusion of aerial perspective.

Wandering through this show, I felt as if I were up in the sky looking down at small, fast-moving abstracted shapes in a panorama of rooftops, pools and other dwellings, leading into the lush world of fields, forests and unblemished natural settings. The two women's work, although drawn from similar sources, provides a contrast of interpretation that is interesting and satisfying from both artistic and emotional standpoints.

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

National Jewelry and Unique Objects Invitational

Fine Arts Center of Tempe, Tempe, Arizona

November 18 - December 28. 1984

by Betsy Douglas

For this exhibition, curator David Pimentel, Associate Professor of Art, Arizona State University, invited 35 artists for their diversity and innovative approaches to jewelry/metalsmithing. The participants ranged from those who make their livelihood by creating and selling their work to those who work in academia. Geographically, the artists spanned the entire United States, from Maine to Washington and Hawaii. This exhibition evidenced two distinct directions in contemporary metalwork: sculpture and wearable art. Many of the invited artists were concerned with individual statements in a sculptural context, including Michael Tom, Jon Havener, J. Fred Woell, Carol Kumata, Gary Griffin, Thelma Coles and Jim Cotter.

Outstanding to this viewer was the work of Michael Tom. His Acceptance, a highly refined holloware/sculpture of patinated copper extended the concept of the bowl into an object of pure abstracted form. This ritualistic vessel has a curved square lid with a circular inset of mokume gane that appears to float in the square opening of the bowl. Equally exquisite was Tom's Maturity, an elegant raised copper container whose upper edge of hammered wires extends upwards at each side to create treelike handles.

A contrasting approach was projected in Here's To Your Health, a metalwork wall panel by J. Fred Woell. This walnut-framed relief is an eclectic collage of found objects, including a flattened Coke can, a rusted knife blank, a tin can lid framing a miniature of praying hands and a broken fragment of gold wire-rim glasses mounted on a support pierced with bullet holes. Woell uses such objects to make a personal commentary on man's condition in a violent society.

Particularly distinctive were works by Jon Havener and Lane Coulter. Working in the visual tradition of sculptor Seymour Lipton, Havener, in Conquistador and Standing on Three, has created two powerful sculptures of blackened brass and copper. These works are aggressive expressionistic three-legged forms that boldly slash and stalk space suggesting walking armor and weapons. Lane Coulter's pewter vase simulating marble thematically opposes Havener's warlike constructions through its serene and classical form and painted trompe l'oeil pink marble surface. Also peaceful in character were the figurative enameled panels of Jamie Bennett, including "Ms. L" with Brooch, which depicts an off-white silhouette of a woman holding a minor executed in soft colors: warm grays, mauves and gray blacks.

The jewelry portion of the exhibition presented work by a number of notable artists, including Linda Threadgill, Linda Watson Abbott, Richard Mawdsley, Leslie Leupp, Al Gilmore, Susan Kingsley, Mac McCall and Kate Wagle. Kate Wagle submitted two brooches and a bracelet featuring delicate patterns of brass fused into sterling silver discs with holes in the center. Linda Threadgill's handsome brooch Patchwork Triangle also incorporated etched geometric patterns of brass overlay viewed through a triangular window of sterling silver. Three sophisticated brooches by Linda Watson Abbott combine irregularly shaped sheets of sterling silver framed in gold with graphic patterns of tiny calligraphy made by felt marking pens. Leslie Leupp explores geometric linear form and pattern in his architectonic-looking bracelets of steel, aluminium and titanium. Richard Mawdsley's Headdress #3 is a pendant featuring a large chased face with a remarkably elaborate headdress suspended from an intricately constructed chain. This neckpiece, made of sterling silver, banded agate and moonstone, enabled the viewer to enjoy Mawdsley's wit in creating an outrageous "goddess" and his incredible skill in tubular fabrication.

"The National Jewelry and Unique Objects Invitational" provided an unusual opportunity for Southwest viewers to see excellent work by metal artists of national and international reputation. In addition, the sculpture and jewelry work presented here evidenced the artists' personal imagery and concepts, which transcend what is popularly considered as jewelry or sculpture. Long overdue, this was the first major national invitational metals show to be held in the State of Arizona since the "Metalsmith" show organized by the Phoenix Art Museum and the Society of North American Goldsmiths in 1977. The Fine Art Center of Tempe deserves praise for their foresight and commitment to excellence in mounting a national exhibition of contemporary metalwork of this quality and diversity.

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

Donald Friedlich, Enid Kaplan

Convergence Gallery, New York, N.Y.

September 18-October 14, 1984

by Vanessa S. Lynn

One of the pleasures of the well-chosen dual exhibition is the enhanced appreciation possible when two divergent esthetic statements present themselves for intimate comparison. This was the case at the show at Convergence where the work of Donald Friedlich and Enid Kaplan comfortably shared a wall case. There is everything to differentiate the two bodies of work: Friedlich's is a minimalist presentation, Kaplan's a constructivist puzzle. Kaplan takes human follies and foibles as one of her primary preoccupations. This extends to her concern for the anatomy of the wearer. Friedlich's subject is art and its quintessential questions. His pieces have a timeless quality. He will also readily admit that the wearer is not formally factored into his work beyond basic concerns of size and weight of the piece. Kaplan's statement is of its time—new wave form and color are strong presences. Kaplan's esthetic is almost baroque; Friedlich's derives from an Oriental-inspired minimalism.

Kaplan has expanded upon her past metal collage to now define a figurative statement. The result is an intricate layering of metals, etched surfaces, cut-away forms and the careful inclusion of the titanium color palette, to create a dancing dangle of elongated bodies and lively heads immersed in conversation and/or confrontation. The formalist investigations of Donald Friedlich render elements to their essential esthetic, striving to make tangible the ephemeral qualities of tension, interruption and, lately, erosion. He employs slate, ivory, golds and touches of titanium to probe his concerns in earrings, necklaces and brooches.

Friedlich's commitment to an Eastern purity is sincere, and it offers him a monumental challenge. The simplicity and order of oriental packaging, the refinement of the Japanese garden, the delicacy of texture found in handmade paper are conceptual influences that find their way into his work. If individual pieces are not always entirely successful, it is because there is no room for error in the vision he seeks. The Japanese make this point in Ikebana—the art of flower arranging. A single misplaced branch can destroy an entire composition, even though made up of only three elements. Friedlich treads that thin line, between bareness and boredom. Sometimes he misses; the spare, elongated earrings of ivory or slate in this collection, seemed too simple to entice. The two necklaces, composed of slate and gold rectilinear forms were set on "chains" of tumbled onyx and gold beads. But round beads and angular centerpieces do not speak to each other—the two elements need to be better integrated.

Friedlich excels, however, in his deceptively simple brooches. All begin with an irregular rectilinear format. Interest is often added by a subtle surface changes—the texture of handmade paper is one the artist favors and successfully accomplishes. One exciting group of pins used a dense slate for the basic surface. The original rectangle was then altered, or "interrupted," by an ongoing dialogue with various materials. In one of many variations exploring the dynamics of tension, a diagonal had been sandblasted into the slate slab, bisecting the "canvas" by a change in surface texture and height. Appearing at first applied, but in fact also sandblasted out of the stone, were three oblong forms whose surfaces were also effected by the original diagonal. Each of these regular elements had a top of 18k gold, whose lower defined edge echoed the dominant diagonal. This dynamic work, one of the most successful in the show, merits closer scrutiny.

While ostensibly a simple piece, comprised of just slate and gold, in Friedlich's masterful hand, the sandblasting technique added the complexity of another material. By altering the texture and layering the heights within these less than 2″ square compositions, the single surface could be read as many. On this particular piece, the light and applied textures actually created seven different slate surfaces. yet, it is only one small stone. In this brooch the artist fully achieved his esthetic intent. When Friedlich is good, he is great! But a "less is more" esthetic is a ruthless one. As in Ikebana, there is no room for a single hesitation. Other brooches in this show that addressed the same concerns, employed the same materials and sought the same subtlety, because of a compositional flaw or too few elements, fell short of the desired impact. Having more than proven that he is capable of meeting his self-imposed demands, the artist should continue exploring and expanding his chosen vocabulary and studying the successful models of his Eastern mentors. In addition, the design tenets of the Bauhaus, as well as the transcendent Suprematist compositions of the Russian painter and theorist Kasimir Malevich, may have additional secrets to reveal.

The more one studies the work of Kaplan and Friedlich in proximity, the more one is pleasantly reminded of just how diverse successful esthetic statements within a jewelry genre, can be. If Friedrich's work is stark and serious, kaplan's is wild and whimsical. For this show she offered three single earrings, one bracelet, two pins, two necklaces, two hair ornaments and one nonwearable piece. The artist sets three criteria for her work: it must "look fabulous," it must work with the body and it must have content. With the exception of the bracelet, which was too abstract for this group, Kaplan achieved her aims—often with great savvy.

In culling the urban environment for Inspiration—city structures, walls, ubiquitous grids and fences—Kaplan captures the frenetic energy of the city in her work. The colors, through a refined use of the titanium/niobium range, refer to the new wave explosion. One is reminded of the energized, linear gesture of Keith Haring's figures, as well as a remarkable relationship to the sculpted heads of New York ceramic sculptor Judy Moonelis. (The latter is Kaplan's close friend, and there is an acknowledged exchange.) Here the artist attempted to take her pieces beyond figural jewelry: she included several mounts for the earrings, so that when not being worn they could still be enjoyed as miniature sculptures. In one pair, a male and female head seem engaged in a lively verbal exchange. When the earrings are worn, the dialogue takes place across the wearer's face, but when not in use they are closely set on a slate background which can be wall mounted. Then one can really appreciate the protrusive barbed tongue of the man and the sly hand of the woman, resting against her cheek as if protecting her owner from the verbal assault.

In Ladies With Glowing Eyes, a pair of earrings paying homage to the punk influence of asymmetry in jewelry, one earring was a clever head, the other, an entire body made in the Kaplan vocabulary of triangular head and torso, wire arms and hair and slivers of dangling triangulated pieces reminiscent of the body's movement. Fastened at their edges with tiny pins, the individual elements move freely with the wearer's motion. When not being worn, the earrings hang on either end of a skewed cross-piece, so that, again, the pieces seem to engage each other both on and off the wearer.

The artist's evolving interest in sculpture prompted her to include one larger scale (20″ high) nonwearable piece in the exhibition. Dancing in the Buins placed a 15″ high female figure, in the characteristic Kaplan mode, within a sort of stage set of charred wood. While possibly a first attempt to claim so large a space for her figures, the piece remained unresolved. Figure and ground seemed at odds. Despite the inclusion of an etched metal plate secured to one of the structural members, the materials remained separate. More importantly, we were given no clues to the curious construction. We knew neither where the figure was, nor why she was there. It is perhaps a direction in which the artist should continue, but this sole exploration remained premature.

Kaplan has a sophisticated design sense; a good understanding of how to balance line and form, color and texture. Within the scale of jewelry, she knows how to use these elements to produce expressive and, sometimes, explosive energy. And she has a keen wit—prancing figures are often humorous not only in their freedom and their pose but also in their detailing—an earring of a head sports a little dangling earring. It is self-referential art, with a smile.

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

A Mano, National Metals Invitational

University Art Gallery, Williams Hall, New Mexico State University, Las Cruces, NM

November 1 -30 1984

by Betsy Douglas

"A Mano" (by hand) was an exhibition of contemporary metalwork by 25 nationally and internationally recognized artists. The exhibition was curated by Kate Wagle who teaches metalworking at New Mexico State University. In her catalog statement Kate Wagle writes that the invited artists are "innovators who have led various trends to extend the boundaries of the discipline of metalsmithing." Consequently, the metalwork presented in this exhibition demonstrates a remarkable range of individuality of expression and includes sculpture, functional and non-functional objects, jewelry, wall pieces and containers.

Among the particularly notable sculptures was Gary Griffin's Construction 84-2. From a base of welded steel and coiled band saw blades a treelike structure rises beside a rod suggesting a bolt of lightning. On a triangular platform created from short welded rods stands a tiny western cowboy boot from which emerges a sticklike rod ending in a miniature replica of a birdhouse.

Also outstanding was Randy Long's Vessel for Solid. In this work an inverted cone penetrates the circular opening in a disc. Employing the marriage of metals process, Long meticulously joins sterling and nickel silver to create an illusion of dimensional steps, which in turn are reflected on one side of a pyramid form. Such details with their multiple levels of appeal invited the spectator to view the works intimately.

Three elegant brooches by Eleanor Moty could be appreciated for their bold form and striking illusion of depth as one looks into the retracted light of the faceted stones of rutilated quartz. The directional planes of the unusually shaped stones are extended into the specially designed settings, creating a totally integrated composition.

Equally sophisticated was Gary Noffke's Cappuccino Steamer of fine silver. This wonderfully whimsical holloware form resembles the hat of the tin man from the Wizard of Oz. Subtle linear patterns are chased into the surfaces of the cone shaped body which is tapped with a tapered spout. Noffke's Mint Julie, a fine silver chased cup; and Billy a delightful small fine silver bucket with a titanium wire handle also demonstrate his refreshingly nontechnical approach to materials.

Helen Shirk's dramatic patinated copper and brass vessels as well as the bold containers of David Pimentel represented new holloware directions for both artists Shirk now works with layered sheets of beautifully colored metal to create aggressive, pointed leaflike forms that curl out of one another. Pimentel's Sometimes Things Just Turn Out Upside Down is a large cylindrical copper container that is richly patinated a blue-green color and has a separate form of red brass and gold foil, which suggests that a large feather has "crashed" into its side.

A primitive, childlike humor is the key to the highly personal imagery of Linda Ross's Yes/No Perfume Bottle, which is an outrageous construction of silver, plastics, turquoise and stones. This perfume container depicts an overripe female figure scowling on one side and smiling on the other, the sides of the container decorated by wishbones and four-leaf clovers.

Personal imagery is also an important ingredient of Robert McCall's metalwork as evidenced in two brooches, Window/Rock (Yuma) and Window/Rock I. These brooches, displayed on a fantasy landscape made of slate, represent McCall's response to seeing ancient Indian pictographs and live rattlesnakes in the desert near Yuma. In his composition he has incorporated symbols of this experience as well as his familiar tiny slide mount fabricated out of silver.

Leslie Leupp's sophisticated playfulness is fully evident in Solidified Reality, Frivolous Vitality and Compound Simplicity. These imaginative structures resemble fantasy toys, suggesting a jungle gym or a whimsical playground Leupp combines steel rods with formica, plastic and linoleum with an emphasis on primary colors Although his creations could be worn as bracelets, but the compositions work well as abstract constructivist sculpture.

The highly individual work of Bruce Metcalf and Carol Kumata are mixed media dynamic images conveying mystery, narrative or social comment. Metcall's Difting over Deserts Again shows the skeleton of a boat lost in the sand over which flies another vessel. In spite of its relatively small size, Kumata's Locked River is a powerful visual statement concerning man's behavior towards his environment. A black metal box reveals bricked up walls at opposite ends Inside is the representation of a chasm with a tiny river blocked by the brick dams.

Of special note were two silver cups by Brigid O'Hanrahan Impeccably crafted conelike forms gently rest in sticklike holders. The precise geometric form of silver dramatically contrasts with the organic looking brown copper structures Equally refined was the work of Rachelle Theiwes Using combined elements of speculum forms, rings, cones and discs, Theiwes creates sculptures to enhance the body, including an unidentical pair of earrings called Gold Disk and a bracelet called Django.

The artists featured in this exhibition should be pleased by the handsome and effective installation of their work by Gallery Director Richard Gehrke who personally constructed a modular system of cases and pedestals.

Considering the exhibition as a whole, most viewers would find it highly successful. The only criticism of the exhibition possibly should be directed to those artists who did not send current work. Since the goal of the exhibit was trends by innovators, up-to-date work would have most accurately represented the current state of metalworking in this country.

The Dona Ana Arts Council and the Las Cruces Designer Craftsmen and the New Mexico Arts Division who contributed to the funding of this excellent metals invitational should be encouraged to host such an event again, particularly since New Mexico has made a genu ne cultural contribution to the Southwest by celebrating metal art a mano.

A catalog of the exhibit is available from University Art Gallery. New Mexico State University, Box 3572, Las Cruces, NM 88003.

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

Amy Anthony: Studies in Aluminum

VO Galerie, Washington, DC

October 27 - November 24, 1984

by Yvonne Arritt

The recently opened VO Galerie at the edge of Georgetown has the ambitious goal of introducing Washington, DC's cosmopolitan but conservative community to avant-garde jewelry and wearable art. In a small, elegant, glass, chrome and white environment, the work of some 50 European, Australian and South American artists is displayed with that of 10 Americans, most of whom emphasize innovative materials and espouse the concept of minimalism. Selected by co-owner Joke van Ommen, past president of the Washington Guild of Goldsmiths, the collection is consistently geometric, linear, simple and especially functional, whether constructed of gold, stainless steel or cardboard. Touches of whimsy appear in the form of wearable feathers, thumbtacks and rubber bands.

In this setting, Amy Anthony, a machine tool and die instructor with a fine arts background, showed her aluminum and stainless steel brooches and wall sculptures during VO's first one-person show. The pieces reflect her enthusiasm and skill at taking aluminum to the nth degree: stressing, carving, breaking the basic rectangle and, finally, adding one wire or strip to redirect the eye and break the plane. Minimalism perfected, these tiny pieces are abstract sketches, shy and reticent like their creator, their textures offering interesting optical illusions worthy of a second or third glance. A grooved slab gently bent; steel wires "sewn" and held by carefully engineered tension; half-inch bars fluted and carefully melted; a trompe l'oeil pyramid produced by wire brushing: Anthony is obviously having fun with the machines she understands so well. Her recent addition of colored inks to define the depths and textures is a welcome touch.

There is a masculine quality about this work; the brooches here were so small that they could be cuff links or tie tacks as well as lapel pins. (The men's jewelry business can certainly use some innovative ideas, and here is a perfect place to start.) Given the physical properties of aluminum, these pieces, including the wall hangings, could easily be much larger without upsetting their composition. Indeed, the scale is too small for the statement, the statement too strong for the size.

This is Amy's first solo show, although she has shared others abroad and won awards and grants in her native New York State. An all-purpose person in tune with the 1980s if she needs furniture, she makes it; if she needs a lamp, she makes one admirable qualities, nonchalant but determined.

The VO Galerie, co-owned by Jan Maddox, metals professor at Montgomery College, Rockville, Maryland, will continue to sponsor shows of experimental jewelry offering Washington a select sample of international ideas in adornment.

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

Martha Banyas: The Mask Behind the Mask

Contemporary Crafts Gallery, Portland, Oregon

September 20 - October 27

by Jalaine Madura

Recent enamel masks by Martha Banyas continue her exploration of enamel in sculptural forms. Earlier pieces dealt with intricate combinations of human, plant and animal forms, the human tendency to "decorate," to assume the patterning of other creatures for projection, disguise or concealment. In the seven works completed during the last year, the artist has concentrated on the expressive imagery of the human face and the varied interpretations of masks that can be placed before the face.

The mask sculptures owe much to a 1983 trip to Bali, where the artist became interested in Indonesian dance and mask forms, particularly their visual impact and spiritual associations. While the sculptures are not direct cross-cultural translations, they represent the assimilation of a host of meanings for masks literal, metaphorical and archetypal — and the incorporation of those meanings toward personal artistic statements.

For example, Dreamer, Dark, Dark is a creation of separate visages linked together. The enamel process is one of fusion, of bonding dissimilar materials into new forms. The analogy of content and form is carried further with the distinct planes on a marble base: this is art of assembly, of uniting separate parts into a composite entity with new meanings.

The mask has surface, depth and its own spirituality. Its structural fragility precludes it from actually being functional; however, its human scale, modeled features and matte surface call to mind many cultural antecedents, such as the masks of Bali, the Northwest coast, or even European carnival vizards. There are deeper associations at work here. The layering of Dreamer, Dark, Dark and its base implies evolution and change, the passage of time and the metamorphosis of forms. The mask suggests the alterations of image, form and identity that humans can assume, as well as the process by which the layers can be stripped away to reveal the reality beneath.

In Unknown, Own Self, the artist has drawn upon the patterning of animals — specifically, the lion fish — for metaphors of concealment and disguise. This derivative patterning is at once contemporary and timeless. The mask rests with its own radiance and ceremony, the fan of striped forms is flamelike and plantlike. Banyas has skillfully balanced these contradictions as well as those of stillness and animation, metal and the suggestion of flesh, fused identities and the fissioning of personality. In one sense, the layers seem to be molting, altering their form as the mask itself changes. Viewed from the front, it suggests the hints of personality that are seen in a human face as well as the willful or unintentional disguising of that face. Viewed from the side, it suggests a stripping away, an exchange of identity or the existence of multiple identities There is the projected face, the self beneath and the shadowy soul beyond.

Both individually and as a grouping — where the play of weathering and experience becomes more prominent — the recent mask sculptures by Martha Banyas present a complexity of meanings and the artistic potential of composite forms. The masks offer insights on human personality, behavior and existence, as well as formal statements of artistic inquiry.

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

Embellishments: Rebekah Laskin and Leslie Leupp

Merritt/Fredric Gallery, Rochester, New York

September 14 - October 20, 1984

by William Baran-Mickle

The wearable objects exhibited by these two artists presented strong and diverse views of jewelry. While both are pragmatic and serious in their constructions and imagery, Rebekah Laskin takes the painter's view and Leslie Leupp expresses a dichotomous approach that plastic is both jewel, backed up by very precise goldsmithing-plasticsmithing, and lighthearted object. There was a common sophistication in the pins, bracelets and earrings exhibited.

Perhaps it was the large size and bright nature of Leupp's work that made me feel that there were too few of Laskin's wonderful paintings in enamel. These circular and squarish brooches were in a soft abstract style using silver foil, reserved line gestures and occasional negative space. Colors created brooding landscapes. Black tones were used frequently, but rather than dominating the field, they empowered other colors with contrast and blended with reds, purples and muddy greens for deep tonal shifts.

Two series of earrings were offered by Laskin, all single ear ornaments. The nonenamel set was dramatic and lithe. All were freely associated geometric shapes. The ear wires extended easily 1½ inches, again in an imperfect, playful geometry in 14k gold. Their bodies were black surfaced with helter-skelter etching reaching to the layers below (brass/copper). The many thin layers were elegantly exposed on the edges and on the backs in a subtle pattern of oxidized lines.

Leupp's 24 works spoke more to the question of what jewelry can be than Laskin's confident and more traditional approach. Earring sets were of such volume that they looked awkward, as were pins 7 inches high. When worn, they all appear as floating sculptures. Aside from the bold character of plastic jewelry in general, Leupp successfully captured personal statement. His works seem to be saying that while jewelry can be fun and worn lightly or playfully, it can at the same time be formally constructed. Making use of common materials such as linoleum and formica, he seeks to dispel some common ideas of wearability and presence.

Leupp made excellent use of found linoleum pieces (from the '50s?) laminated with colored plastics in stripes and dots The dark grays and warm blacks with occasional blocks of white in the linoleum fit the fashion tastes of today as well as good taste in general. (There's a lot of linoleum you wouldn't want to wear!) Many of the pins and bracelets were composed of geometric volumes in bold colors that interacted with planes of focus while being juxtaposed to crisp linear geometric frameworks of nickel or steel wire.

A group of pins that reached 7 inches in length, in simple, elegant proportion, and a group of bracelets 8 inches across used elastic wires as an integral part of their function. They were used to grip the wrist or secure to the shirt while continuing the form all the way to its tip. They added color as well as a passive system for support and tension when worn. Several bracelets were adjustable to the wrist through rubber fixtures in plastic or metal tops. Both were marvelous and simple design concepts.

There were a few rough spots in the show. Both artists offered a piece or two that were well below the standards of excellence of the rest. They almost looked like scaled-down versions made smaller and salable. It may be common practice, even practical, but I usually see a loss of integrity in them. Still, I found only a small number of mediocre works out of a show of 55. For both Laskin and Leupp this exhibition maintained their reputations as high quality, prolific and very creative line artists. Their continual growth is always a pleasure to see.

Pamela Ritchie: Cancelled Icons

The Upstairs Gallery, Mount Saint Vincent University, Canada

August 16-September 16, 1984

by Vita Plume

While at Bay St. George Community College in Newfoundland, Pamela Ritchie became interested in stamps as more than a mundane form of paper currency. Sent to her on letters from traveling friends, they became miniature pictorial references of vicarious adventures and developed into the visual and intellectual vocabulary that constitutes the basis of this work. Ritchie bases her designs on the formal characteristics associated with postage stamps, and she manipulates these elements to deconstruct the stamp, the pictoral image and its myth.

In choosing the stamp, Ritchie fits into the present preoccupation with the nonprecious in jewellery. This "alternative movement" began as an exploration of inexpensive materials, an attempt to reevaluate jewellery as more than the weight and value of precious materials and an effort to make high-quality work available to a broader public. This trend has become fashionable, turning nonprecious work into precious collectibles.

Ritchie's show purported to be a critique of the practice of evaluating an object's worth in terms of materials, whether traditionally precious or trendy and nonprecious. She attempts to reassert the overriding value of the esthetic experience by working with an object of ambiguous value. A stamp can be seen both as a mundane, ephermeral paper product or as highly valued collectible. Ritchie emphasizes this ambiguity by cutting many of the stamps along the cancellation lines, thereby emphaticaly destroying any traditional value. After canceling any previous frames of reference, she inserts the stamp into settings of her own design. Taking the traditional concerns of the jeweller/gemsetter of exploiting the intrinsic beauty, color and value of a gemstone within a setting, Ritchie has replaced the gem with a stamp and has skillfully manipulated the multifaceted possibilities that arise. Her designs are based on the interplay of the pictorial image and the formal characteristics associated with stamps, the serrated edges, the cancellation marks, the colors. She arranges, rearranges and reiterates these elements, resulting in distorted, defaced and decomposed images.

By placing the pieces on the wall rather than in traditional jewellery cases, Ritchie provoked a new evaluation. The viewer entered a gallery of miniature reproductions, each cancelled, modified and intricately reframed into a piece of functional jewellery.

Ritchie uses stamps with a wide variety of images: Prince Charles and Lady Diana, a painting by Renoir, madonnas, kings and queens of France, U.S. astronauts on the moon and floral motifs, and her pieces touch upon a variety of issues: pop images, art, religion, history, politics and feminism. Her work here operated on a variety of levels Some dealt with the manipulation of the formal elements of the design, such as Untitled, Pro Patria. Others, such as Properly Addressed, deconstructed both the image and the myth. While some of the pieces in the show were content with conning the eye, the strongest were those that provoked the viewer to reevaluate the stamp, the image and the "icon."

You assume all responsibility and risk for the use of the safety resources available on or through this web page. The International Gem Society LLC does not assume any liability for the materials, information and opinions provided on, or available through, this web page. No advice or information provided by this website shall create any warranty. Reliance on such advice, information or the content of this web page is solely at your own risk, including without limitation any safety guidelines, resources or precautions, or any other information related to safety that may be available on or through this web page. The International Gem Society LLC disclaims any liability for injury, death or damages resulting from the use thereof.

Related Articles

John Marshall – The Birth of Time

The Work of Jennifer Trask

International Cloisonné Jewelry Contest

Samuel Yellin, Metalworker

The All-In-One Jewelry Making Solution At Your Fingertips

When you join the Ganoksin community, you get the tools you need to take your work to the next level.

Trusted Jewelry Making Information & Techniques

Sign up to receive the latest articles, techniques, and inspirations with our free newsletter.