Metalsmith ’87 Fall: Exhibition Reviews

34 Minute Read

This article showcases various exhibitions in the form of collected exhibition reviews published in the 1987 Fall issue of the Metalsmith Magazine. This features William Harper, Lisa Grainick, Anne Krohn Graham, Richard Helzer, Jaclyn Davidson, Susan Kriegman, Debra Chase, and more!

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

Holloware '87: A National Juried Exhibition of Holloware Made Primarily of Metal

Tower Fine Arts Gallery, SUNY, Brockport, NY

March 1 -April 12, 1987

Tyler Art Gallery, SUNY, Oswego, NY

September 9-October 11, 1987

Roland Gibson Gallery, SUNY, Potsdam, NY

December 6-January 22, 1988

by Susan Dodge Peters

Three years ago Jamie Bennett mourned the state of contemporary American holloware ("American Holloware," Metalsmith Summer 1984). Ideas that had shaped and invigorated holloware design in the 1940s—Scandinavian influences, architectural and natural sources, traditional holloware forms—had withered, Bennett observed, to empty imitation by the 1970s.

The real loss, Bennett wrote, was the Artist's own honesty and integrity "There must be honesty in the making of an art object, whether it is a painting, a building, a ceramic bowl or a metal vessel. Honesty is an act of awareness and a willingness to take risks in presenting a point of view." This lack of esthetic honesty meant that metalsmiths allowed a generation to pass by unrecorded: "Somewhere during the last 20 years we have let pass the opportunity to clearly represent our time and our world view."

Now, less than three years later, there is evidence that Bennett's articulate but grim assessment of contemporary American holloware no longer holds true. Whether Bennett's painful and yet truthful collaring of the situation in contemporary holloware had a salutary effect or whether he spoke of the situation lust as it naturally reached the bottom of its own internal cycle is impossible to know. But something new is stirring in the field.

News of the resurgence in holloware has come via an exhibition "Holloware '87." Organized by SUNY College at Brockport, "Holloware 87″ was a national juried exhibition of holloware. As defined in the exhibition's prospectus, any work made in the past two years primarily of metal, derived from the vessel form, would be eligible. Functional as well as nonfunctional work, one-of-a-kind pieces as well as production work were all included in this definition.

Anna Callouri Holcombe, Galleries Director, SUNY College at Brockport, in consultation with Thomas Markusen, metalsmith and chairman of the art department, organized the show. Thomas Markusen has sponsored four national exhibitions of contemporary metalwork at SUNY College at Brockport over the past 16 years. The first of these shows, "Holloware '71," was an invitational, the most recent, "Holloware '87," was a juried show. Joining Markusen as judges for "Holloware '87" were Randy Long, from Indiana University, and Jamie Bennett, from SUNY College at New Paltz 100 artists submitted slides of their work and 34 artists were selected, 11 of whom were represented by two pieces.

"Holloware 87″ doesn't lend itself easily to critical commentary. Tempting though it might have been to steer this field in a specific direction by means of their selection, the jurors chose a show that reflects the diversity in holloware today. Individual energy and invention, not movements and trends, were the points of this show.

On several accounts, "Holloware '87" is a broad sampling of work in contemporary holloware. Included, for example, are metalsmiths at various stages in their careers, ranging from well-established artists such as Bruce Metcalf and Helen Shirk, to student work—mostly graduate students—from across the country. Concern seems to have been taken to represent metalsmiths who work within university settings as well as those who are self-employed. Interestingly, the number of the metalsmiths in each category was the same.

Difficult though it is to summarize the characteristics of this show, a number of identifiable changes have taken place in holloware in recent years. In his catalog statement, which compares this show with "Holloware '71 ," Thomas Markusen notes changes in materials, particularly the move from silver to other metals, and the decreased emphasis on functional ware.

Artists are always working with and breaking from traditions, and during transitional periods this tendency may be especially marked. To underline that traditional holloware hasn't completely disappeared, the show includes Ron Brady's Apple Blossom Bowl, a piece made with classical silversmithing repoussé and chasing techniques. It was dated 1986 but could have been made two centuries ago. The other end of the spectrum was represented by Susan Hamlet's Vessel Study #2, also of 1986. Austere and intellectual, Vessel #2 is a linear diagram of the outline of a vase, a Constructivist-inspired martini glasslike shape with a swizzle stick leaning against the rim.

Traditions are a satisfying starting point to begin looking at and thinking about works of art. The directions the artist took and the distances traveled are easier to follow. We can find all the elements of a water pitcher—body, spout, handle, lid—in Robin C. McGee's Hewn Wood Water Pitcher, 1985. An inventive of a traditional form, McGee's pitcher has been shaped and textured to look just like a wedge of wood. Driving an ebony wedge part way through the top of the "log", McGee formed pitcher's spout. A realistic looking twig, this one fabricated of metal, serves as the pitcher's handle and the handle for the lid is a bent nail.

Also successful at playing with tradition were Nancy Slagle's Single Serving Teapot, 1986, of sterling silver and Christina Baitz Brandewie's Tea for Two, 1986, of pewter and ivory. Slagle's teapot is a slim, rectangular box with a subtle serpentine curve that suggests a stylized human form. It looks, in fact, incredibly like a woman poised in the midst of a dance—the tango, perhaps—and the spout of the teapot, like the outstretched arm that leads the dancer forward, just into space. The handle is a simple arc that looks as if it were tracing an arm from the shoulder down to a hand on the hip.

Brandewie's Tea for Two also belongs within the scope of traditional holloware, with rounded Aladdin's-lamplike lines in the teapot Two qualities of this tea service are particularly distinctive. The handles of the cups and teapot are sold, but gently concave so that the shadows cast by the handles suggest a depth and hollowness they do not actually have. The set is highly polished and satiny, and at first glance it is easy to mistake the pewter for sterling.

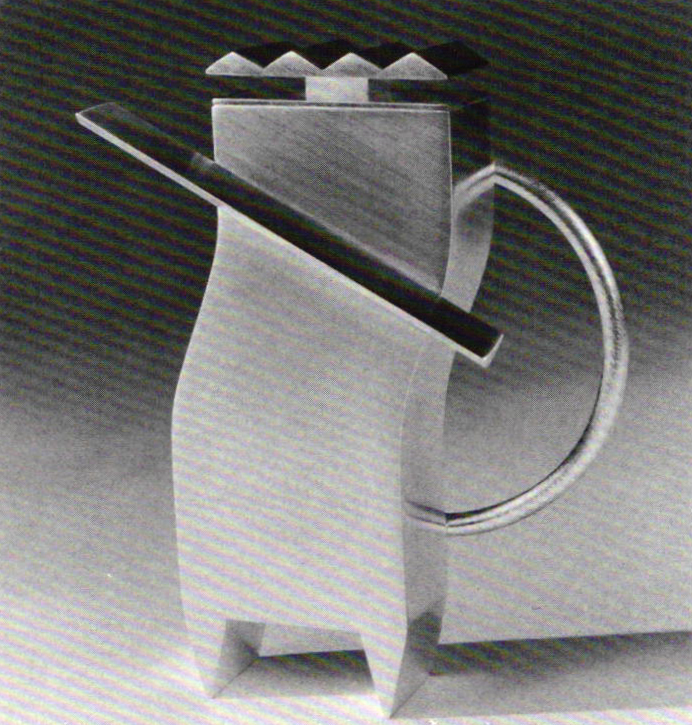

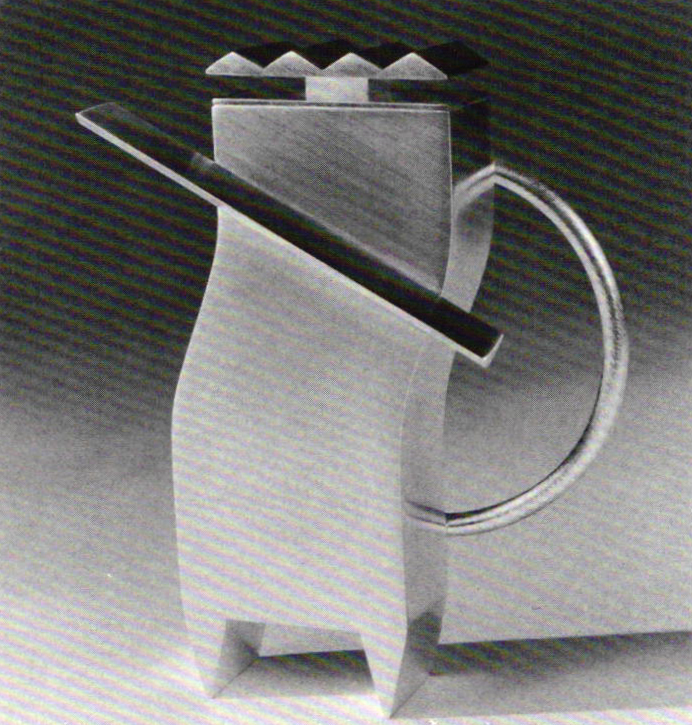

There is something undeniably elegant and intimate about domestic functional objects made in metal. Perhaps it is the preciousness of materials and smallness of scale, but these objects seem to license the imagination to put them to use. Susan Ewing's birdlike or angelesque, Winged Creamers, One Camouflaged beg to be held delicately between two fingers and poured, as does Thomas P. Muir's sleek, architectural coffeepot, Cycladic Figure with his Hair in a Roller Lin Stanionis's two liqueur cups are obsessive, almost sinister in their tiny, meticulous and mysterious details. Liqueur Cup #1, which has a bulbous cup on top of striped stem that ends with a lagged tail, is disturbingly organic. Its tail, which is the base that supports the cup, is curiously like a crumpled insect's leg or a twisted snake's body. The thought of drinking from these cups is unsettling surely they would transform the most innocent liquids into potions.

Because of the very nature of holloware, its functional origins and its persistent reference to the vessel, with its functional overtones, even the most sculptural pieces in this show are tied to traditions, especially to vase and bowl forms. Susan Kingsley's Neorococo Flowering Vase is like a greatly enlarged blossom with exotic stamens and ruffled edges Helen Shirk s Vessel CV26E is as geometric as Kingsley's vase is organic. Explodino from the top of Shirk s vase/vessel is a series of bisecting planes. Some of these planes are perforated, others sold, but the surfaces of the entire piece are covered with patina and oil pastel. The energetic, expressionistic vitality of the drawing instantly identifies this piece as dating from the mid-1980s.

On the cusp between the functional and the sculptural are such pieces as Lynn Hull's extremely simple Ritual Bowl, which has a mysterious hole in its center, ringed with black band, and Komelia H. Okim's large, enigmatic pieces in sterling silver. In Okim's work, which are among the most beautiful in the exhibition, strange concave forms that are part-boat, part-fish, part-moon float or are beached on the top of towers/islands.

Lisa Norton's two pitchers seem at first glance to quality as functional objects, but the appearance is deceiving. Both Norton's pitchers are ultra-simple sheet metal cylindrical constructions with handles and spouts. Embossed on both are written messages such as. Work out a simple, clear code of behavior. See that it is understood and stick to it."

Before the sheet metal was cut and fabricated into pitchers, Norton inked the metal sheets and printed them, and then included the resulting prints in the show. There is a disarmingly obvious quality about Norton's work. It is clearly and simply art about art, but because it dares to be so open about its intent, to be so clear and so simple, Norton's pitchers are among the most engaging pieces in the show.

Bruce Metcalf's work tests the limits of the show s definition of holloware, as metal is his primary material in idea, but not in physical amount, and his references to the vessel form are subtle. In his statement for the catalog, Metcalf describes both pieces as sketches, assembled without plan from ordinary materials." Assembled in Sketch 1985 are a small, painted-wood table, on top of which Metcalf has placed a carved firebrick vessel with a pewter scoop inside, suggesting perhaps a mortar and pestle.

Fish Tables are harder to see strictly within the definition and tradition of holloware. Met calf has made two small wooden tables, which are less than a foot high, and placed sleek, Brancusi-esque pewter fish on top.

The meaning of these two pieces is elusive, and Metcalf intended them to be so "I intended to make a poetic, undefinable and somewhat curious object. I enjoy these two pieces for their modesty and lack of ambition. Formally these two pieces do not command a tremendous amount of attention, but intellectually they do stick in the mind, touching big questions that are felt throughout the exhibition.

What, indeed, are the boundaries of holloware? How hollow is hollow enough to qualify as a vessel form? What about materials? As a term, holloware has been traditionally associated with silversmithing, and then, gradually with metalsmithing in general. In mixed media work, how much has to be metal for it to remain within the precinct of holloware? Is it the physical percentage of materials involved that places Metcalf's work within the domain of holloware, versus woodwork, versus ceramics?

Such questions are exasperatingly petty and captivating in turn Considering Metcalf's work in the broader category of sculpture, in which they clearly also belong, these questions are immaterial. Within the realm of crafts, though, they take on other meaning.

Holloware, as defined in the exhibition's prospectus and as explored by these 34 artists, is a broader field than it was in the past. The very flexibility of definition has encouraged, perhaps even permitted, the regeneration of this area of metalsmithing. But definitions to be useful must also be precise. There are without question innovative pieces in this show that fit within the traditional definition of holloware and yet are absolutely unique, utterly contemporary.

Whether or not Metcalf's work qualifies as holloware is an intriguing issue. On one level, one might wonder if Metcalf really belongs in this show. Did his stature in contemporary metalsmithing, more than the specific work itself, account for the inclusion of his work here? Did the jurors stretch the definition just for him? Or is Metcalf's challenging work here intentionally to force the issue of definition? As the most blatantly sculptural and thus the farthest removed from traditional holloware, Metcalf deals openly with ideas that are brewing behind the entire show.

For the individual work it includes, the artists it features and for the issues it raises, "Holloware '87 is an exciting exhibition, which proves that artists working with holloware are once again making honest contributions reflecting their own times and world views.

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

Fashioned in Metal: Debra Chase

National Ornamental Metal Museum

April 5-May 31, 1987

by Linda Lindeen Raiteri

At the preview for her first solo exhibit, Rochester institute of Technology graduate Debra Chase refused to sell her Endangered Species Neckpiece. She had fashioned this graceful ornament from the remains of a broken tortoise-shell haircomb, which she shaped to resemble dancing dolphins, and from pieces of whale ivory, fresh water pearl and sterling silver, which she shaped into two slumping bears. She would not sell the neckpiece because she will never be able to make another like it, she places a higher value on the lives of endangered than on what she may make of the remnants of their lives.

One does not expect this reverence for and celebration of life in an exhibit dominated by clothing made from stiff, transparent, anodized-aluminum screen. Yet there is grace and joy in every piece Chase has chosen to use anodized screening because it allows her "to explore clothing as barrier, protector, and container, is transparency allows [her] to experiment with the way space is defined.

Evening Ensemble, a two-dimensional tuxedo and ball gown made of screening, plastic, paper and glass hangs against a wall waiting for a William Powell and a Myrna Loy to don the ensemble and go out for a night on the town.

Clothing, Chase says, "is a metaphor for our celebration of being human, our rights of passage, our definitions of ourselves. By creating sculptures of clothing that no one can wear, she feels she is making things that everyone can have.

Anyone can step, metaphorically, into the kinship of three Sisters. The three suspended and slightly overlapping kimino shapes, each in a different mood, indicated by the different colored trim on the sleeves, recreate the closeness and the individuality of joined lives.

Since 1985, Chase's work has become three-dimensional, representing the life and/or life attitudes that can be donned, as clothing can be put on—clothing as container for, and perhaps manifestation of, the spirit. She recalls these sculptures Life Jackets.

Shaped like Happi Coats, pieces such as Aquarium Coal a cutout of a woman swimming through spirals of light within the three-dimensional container made of screen, or a cutout of a woman wearing a green leotard, holding a green apple within the jacket called To Be In New York represent moments in her life. The physical suspension of the cutouts echoes first, the buoyancy one feels in water and second, the perfect balance of a fine scale.

Four strapless dresses with bustles make up the series New York Debutantes. Within each dress, a woman is suspended. Each woman has a name and is painted in a characteristic outfit. Each gown is embroidered with symbols of the woman's interests and desires, cruise ships, fine wine, cats, birds, telephones. Each is a talisman for the woman, an affirmation and a celebration of the corresponding life.

In Chase's kimono-shaped Spirit Coal, one can best appreciate the qualities of her chosen material. Here, the strength and delicate transparency of the screen protect and expand the space surrounding the drifting shape of smoke, that represents the spirit within. Spirit Coat was completed days before this exhibit opened. With a dimming light shining on this piece, the spirit suspended within the Life Jacket disappears.

There is a story here, a magical tale, as in every piece in this exhibit of Chase's work. Her strongly narrative work clarifies. What you want exists. Step into it.

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

Susan Kriegman: Brooches and Containers

Henry Chauncey Conference Center

Educational Testing Service, Princeton, New Jersey

March 2-April 30, 1987

by Marjorie Simon

In this latest work Susan Kriegman reveals her debt to Heikki Seppä, using mokume-gane in organic forms scaled to the human body. Form and pattern are carefully balanced so that neither dominates in the 17 brooches; and containers presented.

Mounted at eye level, in groups of three, the forms become more complex as the eye travels through the show, with the simpler, subtler, more self-contained forms presented first. The more complex pieces rely less on patterning, making greater use of negative space. The brooches all work as objects and their display in frames emphasizes their visual integrity.

Though carefully designed, the pins appear to be spontaneously executed. The third group reflects an experiment with line in the use of the striped pattern. They are worked more directly into the metal without the intricate planning of larger sculptural pieces. Their humor emerges from organic shapes that are highly suggestive. In these pins lurk the jaunty energy of a torso in motion, dancing ladies thighs, a flying apron, a can-can dancer. Such soaring forms encourage "flights" of fancy. Less successful were a group of flat pins using tubing as line to open up forms without adding weight.

The containers recall the pure forms for which the artist is better known, and they provide an eloquent counterpoint to the more spontaneous pins. They are visually strong, emotionally powerful. Although the container is a more controlled form, an unexpected element appears as a playful appendage emerging from the top of one voluptuous form. The work quietly engages the viewer, inviting one to contemplate more closely the stripes in an overlapping ruffle against the traditional wood-grain, mokume-gane pattern surrounding it.

Flanked by the more recent brooches, the containers foreshadow the last group of pins, indicating the direction Kregman may be headed. One looks forward to further exploration of the graphic possibilities of line and space in a less two-dimensional format. Already the body-scale brooches reaffirm the artist's commitment to the dynamic equilibrium of form and pattern.

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

Jaclyn Davidson: Jewelry

Susan Cummins Gallery, Mill Valley, California

May 4-May 30, 1987

by Roberta Floden

Reminiscent of the gargoyles that embellish Gothic cathedrals or those fantastic creatures that dwell in Hieronymus Bosch's Garden of Delights, Jaclyn Davidson's elegant sculptural jewelry does not sit comfortably in a gallery of contemporary art and craft. Her scrupulously detailed, lost-wax cast, sterling-silver and gold figures, hanging from rows of simple, round beads and adorning rings, are more medieval than modern.

And like medieval grotesqueries, they are informed by disparate juxtapositions: the frightening with the peaceful, the serious with the absurd, the horrible with the beautiful. Such incongruities, along with her idiosyncratic titles and inspirations (that often provide little toward understanding her images, jolt the viewer out of conventional response and invite closer inspection. In her pendant Super Creeps are a plethora of dissimilar elements: dismembered arms; a belligerent dog who, according to Davidson, is "keeping evil spirits out like the Fu dogs that guarded Chinese temples"; a naked androgenous person surrounded by "gold anxiety creatures." Smiling whimsically because he has his head in a "heal-all" pyramid, all of this suspended from a beautifully designed necklace of sterling silver with gold leaf inlay, cast, chased, engraved and colored. Both compelling and interactive, Cultural Complex pendant has a snail-like creature with a female head sitting upon the back of a lizard whose tail forms a cobra.

Many of Davidson's pendants depict creatures from fantasy and folklore. In Hiding Oni, an exquisitely wrought basket reveals an ugly devil-like creature hiding therein (Referring to a Japanese custom of throwing parched beans in each room to rout the devil at the end of winter, Davidson says that her "oni is hiding under a basket to escape the beans.") Similar to the figure in Edvard Munch's The Scream, the female in Davidson s Pandora pendant holds her hands to her ears as the silent sound emitting from her rounded mouth assaults the air. Lines of anxiety stream down her like tears, continuing on the back to become the lines of a scallop shell which—like Pandora's box—opens (with a duck's head handle).

Davidson's rings tell their own concise little stories. Zebra grazing peacefully with jackals lurking in the background is "just like my average day," she says. Rings, like Wolves hunting for the hiding rabbits and Cat trying to get birds on other side, combine the miniature animals with fine enamel work. Often rings are formed from, rather than embellished by, the gold and silver creatures: the legs of Female dancer with theater masks curl around the finger.

The surfaces are rarely left plain. Because her pendants have up to five pieces of sculpture soldered together, Davidson uses engraving techniques—naturally and artfully—to cover the soldering seams. She also burnishes in gold foil to enhance and to give texture lo her silver pieces. Although her beads are subdued in color, they can call attention to themselves and at times seem to clash rather than balance with the pendants. But the beads are a separate item; often graceful diminutive hands holding hooks that connect the necklaces to the pendants, making the pendants independent and interchangeable.

Despite an evident mastery of metalsmithing, Davidson's techniques are not the focus. Instead, one enters irresistibly into her complex visual and mythological images. Indeed if one needed derivations, instead of modern or medieval, perhaps archtypal is the more accurate word. And like those images that swim up from the psychological depths, her jewelry derives its power from the ability to transcend all sense of time or style.

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

Enamels '87

Plum Gallery. Kensington, MD

April 12-May 5, 1987

by Dalene Barry

Putting late-20th-century enameling into perspective is a tough job. Reflecting on an exhibit such as "Enamels '87," you wonder what could be new in a medium that has seduced artists, swordsmen, dilettantes and curators for 25-odd centuries. Not a lot was "new in this exhibition, but most of the 49 artists represented offered the finest workmanship available in enameled jewelry, sculptural works and wall pieces. A survey of the award-winning works (five Jurors Awards of Merit and one Special Newcomer Award) might give an overview of what some of North America's top enamelists are doing today.

A rhomboid brooch by Celia Braswell of Bethesda, Maryland, in muted tones of gray with blushes of warm tans, was a free-form study of opaque and transparent enamel. A light appeared to glow from within, through depths of shadowy forms. Achieving an almost marblelike mingling of colors, Braswell's domed piece seemed cut from another source. The surface was interspersed with small bits of matter, as if embedded with petrifried leaves, stones and small fossil forms. Her mastery of abstract painting technique allowed her 10 explore fusions of color in multiple layers, utilizing the unique blending qualities of enamel.

The exquisite craftsmanship evident in James Carter's two brooches Pipedreams I and II, brought this Carbondale, Illinois jeweler to the top of the show for metalsmithing ability. Enamel on these brooches served as a decorative medium. Tiny bursts of color, carefully contained by gold cloisonné wires, highlighted deep blue and black enameled cylinders, each curved upward 10 support a golden finial. Bangles dangled and beads sparkled from adjacent arms, conjuring up images of a golden fancy, reminiscent of a sultan's lair.

Peggy Hitchcock played a visual game with her audience in Raining Frogs. Frogs, fish, a cat and background linear patterns all were juxtaposed to one another to bring the viewer forward for a better look, then back away for perspective, then closer again, head tilted to break the code. Then, there was the question of the enamel itself. This Seattle enamelist's technical ability and interweaving of other media in her designs made her the master of her tools. Hitchcock used enamel, as she did paint, wood, metal and photography, not for its own inherent beauty, but as a complementary medium, subservient to her overall mastery of design.

Belle and Roger Kuhn's enameled brooches were pure and elegant in form, but far from simple in their thoughtful execution. Their two-inch-square brooch was a quiet study of color and depth. Subtly blended tones of transparent blues formed a background grid for diagonal stripes in blues and pinks. The stripes floated over the transparent background, separated visually by a deep purple, opaque shape. A free-floating, sterling frame anchored the enamel, secured by tiny silver bars echoing sections within the enameled grid. This Bethesda, Maryland couple has long been known for their fundamental approach to enamel and design, exploring the basics of what enamel can do and how the result can be enhanced by a rectilinear, perfectly complementary setting. A special bonus—their brooches are equally handsome on women and men.

Janet Marsano's Blue Fingers, a freestanding table piece of brass and plexiglass, supported a removable enameled brooch, offering the viewer a whimsical hands-on opportunity. Innovative design was a strong point in this Columbus, Ohio enamelist's work A strip of brass across the lower portion of the table piece featured cut-out shapes of hands, which were folded back flush with the plexi surface. This simple trick made the positive and negative spaces work double duty, hinting at a moment's suspension in lively animation. The enameled brooch repeated the theme of upheld hands, reaching for the stars, their own blue fingers, perhaps a velvet glove? It was anyone s guess—much to everyone's delight.

Betsy Crump's series of New Mexico Mourning Pins were awarded a special prize, sponsored by the Northern California Enamel Guild, for exceptional work by an enamelist who had not previously won a national award. The three diminutive brooches were architectural in scope, suggesting horizons beyond the limitations of physical size. Black enamel, in both glossy and etched finishes, was set against gold frameworks in simple, elegantly streamlined shapes. These highly refined pieces from Norman, Oklahoma, gave enamel a sophisticated design theme rarely achieved in this seductive color medium.

"Enamels '87" jurors gave honorable mention to Christina Gibson-Sears. Santee, California, Kathryn Regier Gough, Huntington, New York: Alison Howard-Levy. New York City; and Harry Weiss, Bethesda, Maryland.

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

Richard Helzer Exhibition

Flossie Martin Gallery

Radford University, Radford, VA

February 6-22, 1987

by C. James Meyer

Radford University recently mounted a one-man exhibition of Montana artist Richard Heizer's work. The exhibition was comprised of 10 wall panels with a piece or multiple pieces of jewelry attached and four free standing sculptures.

The wall pieces, which were arranged n four separate groups, consisted of framed plexiglass with one or more pieces of jewelry attached, along with drawings on the plexiglass that related to the imagery of the jewelry and/or its construction. There was a free use of materials, the neckpieces were simple hoops of anodized tantalum with a fabricated silver closure, suspended on a hoop were pendant forms small twigs of wood, twigs reproduced in metal, found pebbles with holes drilled in them, metal constructions, etc. . . one pane that I felt was particularly strong, contained a series of gestural images drawn in colored pencil. Centered in the frame was a brooch, a hard-edged fabricated bronze and silver form that contained inset slices of prismacolor pencils with their painted edges and central dot of color.

In his statement that accompanied the exhibition Helzer states, "I no longer feel bound to a tour de force of complex constructions or workmanship. Instead, I am concentrating on. . . spontaneity and directness. Among my interests are: the image as symbol, drawing in the third dimension, and the use of nonprecious materials. . . Much of this was accomplished. The objects were refreshingly crafted. Appropriately, the intent was not to dazzle with technical skill, yet the objects were made with integrity.

The jewelry raised important questions. I found the show to be very eclectic in the use of imagery and presentation Claus Bury certainly isn't the only one to have taken jewelry out of the dresser drawer and put it on the wall, but he did it a long time ago and did it so well that it is difficult for an artist to do the same and not have that strong reference. (l feel that only the recent Jamie Bennett constructions with enameled objects have taken the idea a step further).

The forms were also eclectic. The use of multiple, interchangeable forms on the neck-ring remind one of Hermann Junger's early 1980s work. The dimensioned-parallelogram brooch is precedented by a mid-70s Bury piece. Clouds and lightening bolts are to be found as recurrent symbols. Are they still valid 15 years later? Am I too demanding in wanting to see less generic imagery? The spontaneity that Helzer is searching for exists only on the surface it ends up like eating day-old bread, nutritious but a little stale.

The jewelry/wall pieces raise the question of wearabilty. Here the mode of presentation has definite pros and cons. To the viewer, having the objects right there, not once removed by a sheet of glass, gives the objects a real presence. The use of drawing along with object has both positive and negative effects. Again, I quote from the artist's statement: "It is my hope that the drawing and the jewelry are in harmony. . . (giving) the viewer sufficient information to understand the roots of each object." In the case of imagery development and, when used, color palette, I found the drawing supportive of the object. However, I found little technical notations very distracting. As stated earlier, the objects were not meant to be technical tours de force.

As a jeweler these drawings gave me no special insights that weren't obvious from looking at the piece. Is it important to a nonjeweler how a silver catch is attached to a piece of tantalum? Finally, the jewelry was wired to the wall piece from the back. While I acknowledge this necessity for security reasons, the restricted access combined with the fact that placing jewelry on a wall in a frame calls out, "Hey, I'm art, look at me, gave one the sense that the artist never intended that the objects be worn. It became a bit pretentious I thought we had gotten over our paranoia about being "artists."

Not surprisingly, the sculptures showed similar strengths and weaknesses as the jewelry. Again I found them eclectic, with the strongest influence being the work of H. C. Westermann. In some ways, I found them overly crafted. The use of formica offered a distracting edge. The substitution of a painted surface might have had more personality. I enjoyed the objects sheathed in sheet lead. The recognizable stick that takes on a different personality being dark gray and metallic, combined with rocks, was successfully juxtaposed to rectilinear colored forms. Helzer states "each piece in this show attempts to project the illusion of a mysterious event or place." However, it is as if a known formula for success was followed. As with the jewelry, I didn't get a sense of risks being taken.

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

Anne Krohn Graham: New Age Totems

Elaine Pottery Gallery, San Francisco, CA

April 21-May 23, 1987

by Carrie Adell

In a statement on this exhibit, the artist declares that she was inspired by architectural structures and patterns found in urban spaces, such as lattices, grids, gratings, windows and fences.

The works themselves, 60 pieces of anodized aluminum jewelry, were grouped into three different yet visually related collections. Most visible and dramatic were the pectorals, cuffs and earrings, all of which were constructed in bread planes of gently embossed geometrics, overlayed and accented with anodized areas of color. Graham here extends concepts developed for a show at The Worcester Craft Center in October, 1985 (see Metalsmith Summer 1986, pp. 58-59). Now the surfaces are further elaborated, layer upon layer. Echoes of patterns on the broad embossed surfaces appear in miniature, in photoetched and anodized areas of embellishment. Her statements are even bolder now.

A second grouping, predominantly brooches and pendants of perforated patterns and layered lattices, were small (about 2½ x 2½"), more intimate compositions, intriguing in their overlay of complex color, a counterpoint to the cutout areas. Brooches and pendants were each provided with their own appropriately signed and colored, wall plaque environment, creating dimensional designs, in the manner of Mondrian. The brooches themselves were rectangular, each framed in a field of sterling silver sheets. These rigid armatures were finished in a soft sandblasted surface, enfolding and connecting three to six layers of anodized perforated patterns, reiterating the rhythmic regularity of the perforations in graduated tones of contrasting colors. The "frames" and layers are cold-joined with tiny decorative nuts, bolts, rivets. Different pierced and anodized patterns appear on the flip sides of all the layered brooches. They can be suspended, either side out, on a choice of neckpiece structures called Torii. These architectural lattices are of softly finished aluminum tubing, carefully arranged perpendiculars, the lips of which terminate in caps and finials of mechanical fitting. One open-ended horizontal tube receives the pin-stem of any of the brooches interchangeably, converting it to a pendant.

Body sculptures, exhibited in four clusters or architectural arrangements, made up the third visual grouping. The calfpiece was constructed of heavy aluminum rod, bent in a series of perpendiculars, which could be wrapped around and rested upon the wearer's calf in a choice of positions. Ankle, arm and wrist were similarly provided for, in a finer gauge of aluminum rod jewelry, festooned with fixed and mobile bands and rings and with the subtlest of anodized colors.

Graham treats aluminum with the respect usually reserved for precious metals. She has reached her goal "to achieve a dye-colored surface that catches ambient light to create a vibrant interaction, which is perceived as an iridescent transparent surface layer." It's the most sensitive and subtlest use of color I've seen on aluminum.

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

William Harper

March 9-April 4, 1987

Susan Cummins Gallery, Mill Valley, CA

by Carrie Adell

William Harper is a self-proclaimed "Eclectic- Man." He draws his subject matter, symbols and imagery from myths and religions. He borrows stylistically from past cultures. His jewelry communicates the feel of the ancient, of something dug up out of the past, yet, it speaks simultaneously in a contemporary idiom. Harper wants to jolt the viewer by combining unexpected materials and techniques and by the juxtaposition of content both sacred and profane.

How then is the viewer jolted? Perhaps the jolt comes from discovering that some of the fragmented elements in Harper's elegant designs are of common origin (bike reflector bits in textured red plastic), materials seemingly inconsistent with the gold, gemstones and especially the opulent surfaces of cloisonné enamel.

It is in these enameled areas that Harper celebrates his art. Here, the viewer glimpses Harper's commitment to doing and making, his skill and dedication to delicate and time-consuming processes. The echos of cloisonné enamel areas found in the bits of bike reflectors gives us an indication of Harper's attitude towards "preciousness" and its attendant associations. He reminds us that Western contemporary values stand side-by-side with those of other places, people and circumstances.

Does the viewer get a feast of visual and conceptual complexity? I would say yes, and then some. The most recent work in this exhibit, a series of wizard's wand brooches, demonstrates visual power and strength beyond any supernatural magic with which they might be invested. Shown as vertical forms, they are mostly long brooches (up to seven inches), reassembled fragments. deeply framed, heavily enriched with cloisonné enamels, textured, offset bezels and a variety of metals and other materials. These images are less referential than found in earlier series, some of which were also shown, where masks, skulls, fetishes recall the iconography of primitive cultures, somewhat caricatured.

Harper's titles lead the viewer to connections and associations that the images alone do not communicate. They enrich the experience of the works by triggering our strong feelings and allusions to religion, morality, status of whatever is important to us about these subjects. Harper is telling us, perhaps, about the homogenized nature of the world we now live in, where we have access to the myths, histories, rituals and symbols of all cultural heritages, ours for the taking, although not always in the spirit in which they were created.

Yet, what happens to these enriching experiences of the jewelry when a piece comes out of the case and onto the wearer? Away from the antiseptic environs of the showcase the piece is transformed by its new environment, a human being, herself a walking warehouse of visual and emotional associations, and by the event of wearing, itself charged with content that brings the wearer and viewer together. The title may tell how cultured, or clever, or well traveled the maker is, but the work tells more about the maker as an artist and a human being.

The work stands for itself, and for its process of creation. It alone tells about the balance of line, form, color, texture chosen for use by this artist at this particular time in this particular piece. It tells that the artist loves color and sings with color. It tells that the artist values the spontaneity of his metalworking processes over more "refined" techniques, that primitive is valued over polished, that fragments are all the story he wants to tell, that mystery is important and that his images inherently embody greater power than their titles.

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

Lisa Grainick

VO Galerie, Washington D. C.

May 21-June 18, 1987

by Nicholas Ward

All the work produced for this show is fabricated from black acrylic sheet, 1/16″ in thickness, bent, glued and worked to a satin smooth finish. The craftsmanship is such that the seams joining the various hollow sections of each piece are barely perceptible. On first sight, the individual works appear to be either solid castings or carved from material such as ebony. It is a surprise to handle one of them to discover the actual lightness that belies the density and visual weight of its material. Formally, the works consist of fairly regular geometric solids such as discs, cylinders, triangles, cubic and rectangular shapes that in some cases are notched, divided or cleaved with fins and protrusions. Because of their proportional relationship, and the uniform finish that displays no handwork, these objects have an industrial, even mechanical look that gives them a somewhat impersonal, yet cool, elegant quality.

Although the pieces are similar both in terms of materials and techniques, Grainick's work falls into clearly defined thematic groups. There are ones recalling architectural motifs, houses, obelisks or simple monuments. There is a cluster of small discuslike brooches with their form changed either by segmented cuts or altered with geometric additions. By contrast, other brooches have long, narrow, tapering bodies that resemble projectiles with fins. One piece that stands out, partly because it is the largest object in the show, resembles the upturned keel of a boat or the top half of a submarine hull with its contours flowing to two points on either end.

Perhaps the most enigmatic group of works are recent ones that have written inscriptions roughly scratched into their surfaces. These appear 10 outline the artist's thoughts concerning their inception and evolution. One example reads, "Black shouldn't go circle wise. I tried to make sculpture from a flat broken record but it ended up to be jewelry" An apparent concern seems to be how to treat an object's surface in a meaningful way while eschewing decorative two-dimensional effects. This particular piece also has a recessed center containing inlaid gold. The combinations are starkly contrasted and quite sophisticated in execution.

Overall, Grainick appears to find a sinister fascination in the world of streamlined forms that we now take for granted, and perhaps we would rather not be reminded of some of them because of their ultimate purposes. Machines, missiles planes, ships are evident as fundamental sources of inspiration. She is obviously uncomfortable with the preciousness of traditional jewelry, wishing to infuse her work with a significance beyond its role as adornment These wearable sculptures are a personal distillation of many forms that can embody universal menace or unease. She approaches these private feelings in a positive manner by transforming them into beautiful objects.

You assume all responsibility and risk for the use of the safety resources available on or through this web page. The International Gem Society LLC does not assume any liability for the materials, information and opinions provided on, or available through, this web page. No advice or information provided by this website shall create any warranty. Reliance on such advice, information or the content of this web page is solely at your own risk, including without limitation any safety guidelines, resources or precautions, or any other information related to safety that may be available on or through this web page. The International Gem Society LLC disclaims any liability for injury, death or damages resulting from the use thereof.

Related Articles

Naum Slutzky Jewelry at the Bauhaus

An Interview with Milt Fischbein

Hans Jaenisch: Jewelry Shows its Colors

Recent Sightings: SNAG’s first Exhibition-in-Print

The All-In-One Jewelry Making Solution At Your Fingertips

When you join the Ganoksin community, you get the tools you need to take your work to the next level.

Trusted Jewelry Making Information & Techniques

Sign up to receive the latest articles, techniques, and inspirations with our free newsletter.