Jewelry Design: New York State Artists Exhibition

6 Minute Read

For the "Jewelry Design" show at the Johnson Museum of Art, Louise Porter, Coordinator of Crafts, selected both jewelry and sculpture by New York State artists. She was especially drawn to artists oriented toward jewelry design but working in the less confining area of sculpture. She would like to encourage metalsmiths to test the boundaries of jewelry. This show featured some extremely fine pieces that would delight and intrigue anyone seriously interested in metalwork. Unfortunately, some commonplace, trite pieces were also included which for me marred the exhibition.

Jewelry Design: New York State Artists

Herbert F. Johnson Museum of Art, Cornell University, Ithaca, New York

June 21-August 21, 1983

Porter included both recent and older work of certain exhibitors to give viewers a sense of the artists' progression. Others had only current work on display. However, this lack of consistency coupled with a failure to include dates on the labels, caused the sense of progression to be lost.

The most outstanding works in the show were the enamel brooches of Elizabeth Garrison. Garrison's work seems to constantly change and grow. She is not afraid to abandon a style that has been fully explored and move on to something new. She is neither limited nor overwhelmed by her technical virtuosity. This current series of small brooches and a bracelet combined cloisonné enamel forms in radiant colors with found objects. Although some combined so many elements as to become confusing both in imagery and form, her simpler pieces were impressive works of art. In her most successful Brooch she juxtaposed the profile of a person and the number one above a shimmering enamel rectangle divided into three sections. The overall balance of form, imagery and color in Garrison's design resulted in a remarkable piece of jewelry, one that was easily wearable yet contained a significant artistic statement.

June Jasen's cloisonné enamels were another highlight in this exhibition. Her Interchangeable Dress-up Doll Necklace consisted of a paper-doll-style figure dressed in a modest chemise laced on a cord. On each side of this form was a clothing outfit, one a ball gown reminiscent of a 1950's prom dress in soft pinks and purples and the other a pair of lounging pajamas in brown and beige. It was left to the wearer to decide how this piece should be worn; all three pieces at once, one at a time or the doll figure "dressed" in an outfit. While displaying tremendous technical skill in the subtle color gradations of her enamels, Jasen's main emphasis was on the humorous quality in her work. It was to her credit as an artist that this playfulness never overshadowed her concern with form and proportion.

Ruth Nivola, coming from the world of fiber rather than metal, offered a fresh approach to jewelry. Her neckpieces, akin to ancient primitive art, were nevertheless very much her own and very up to date. Joyful Tears was composed of an inch-wide choker crocheted in gold metallic threads from which four crocheted golden threads hung to the waist. On each thread was one elegantly wrapped bundle interspersed at a different height. Each precious bundle consisted of the same crocheted threads enclosing a swatch of luxuriously colored oriental silk. The total effect was of an exquisite personal statement.

David Freda was one of the artists whose work was shown as a progression. His early work, apparently influenced by the jewelry of Albert Paley, was well crafted but uninspired. However, following a trip to Alaska and a stint as a taxidermist, a style, imagery and even technique all his own has emerged. Freda has developed a process he calls "slumped" aluminum, achieved by heating the aluminum in a kiln until it melts, forming a soft wave pattern.

Through experimentation he has also evolved a method of enameling on aluminum which he characterizes as very spontaneous. His most accomplished piece Primordial Transformation (Open-Face Jewelry Box) is a small landscape. On a lazy-Susan-style base he created a background of slumped aluminum with a glittering enamel surface. On this surface were placed two neckbands in concentric configuration and a mummified baby snapping turtle. Within the neckbands were the highlight of the piece, six superb sterling silver eggs, each with a lustrous pearl-like finish. Whole, perfect eggs rested next to broken eggs seemingly left behind by newly hatched turtles.

The illusion of spontaneity projected by the cracked eggs belied their meticulous craftsmanship. Unfortunately, not all elements of this assemblage were fabricated with equal sensitivity and subtlety. In comparison, the ginkgo leaves on the outer neckband seemed contrived. Either neckband could be adorned with any number of eggs by means of a small loop on the bottom surface of each egg. This allows the wearer, in composing the elements of the neckpiece, to add her own creativity to that of the artist, something Freda felt was important.

Lynn Duggan was also represented by both past and current work. Her earlier work was based on the forms developed by her teacher Heikki Seppä, without conveying anything new or different. But a new piece, abandoning the Seppä forms, showed positive results. Her Reliquary was a well proportioned, lidded copper container with a yarn and bone handle. Two parallel concave horizontal bands encircled the body of this otherwise convex shape. The bone wrapped with copper wire was attached to a wrapped yarn cord which formed a handle that nestled within the lower concave band. Numerous contrasting elements turned this deceptively simple piece into an original statement. There was the imperfection of the pitted bone versus the perfection of the well-made container; the soft yarn of the handle versus the hard metal; the texture of the hammer marks covering almost the entire container versus the small area of smooth surface on the lid. This appears to be a promising new direction for Duggan.

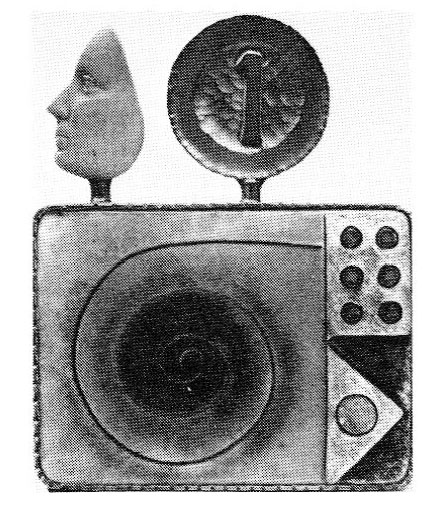

Judith Mitchell Horowitz showed traditional, sculptural jewelry in sterling and 18k gold. Though not breaking any new ground or taking any risks, the work was finely crafted. Much the same can be said of Gammy Miller's woven linen neckpieces with shell shards. Hanna Geber was represented by cast sterling jewelry which was not nearly as interesting as her ceremonial pieces. Charles Eldred's sculpture Jeweled Appliance (Mower) was so far removed from jewelry design that it was difficult to relate to it within the context of the show.

The jewelry of Steve Kolodny, Susan M. Gallagher and Harriet Forman Barrett was decidedly mediocre and boring, similar to what could be seen at any local craft fair. Louise Porter, the exhibit's curator, justified their inclusion in the exhibition for two reasons. First, she hoped that by including these inexperienced but promising artists in a museum show she would encourage them to strive for museum-quality standards. Second, she felt their work would be more accessible than the other pieces in the show to museum visitors unfamiliar with contemporary jewelry. She feared that visitors exposed only to highly sophisticated pieces would be turned off to the entire show.

While both these sentiments are laudable, I am not certain either goal was achieved. By including inferior pieces Porter could have unwittingly inferred to both the creators and the viewers that this was museum-quality work. Furthermore, although experimental, nontraditional work might alienate some visitors, I think second-rate work would have the same effect. I am sure most visitors could easily relate to the traditional, finely crafted jewelry of Judith Horowitz, ensuring that no one would find the show totally inaccessible. The Johnson Museum is to be commended for its long-standing support of crafts through numerous exhibitions. But in the future I think they would better serve the museum-going public if they limited their shows to only top-quality work in all fields.

You assume all responsibility and risk for the use of the safety resources available on or through this web page. The International Gem Society LLC does not assume any liability for the materials, information and opinions provided on, or available through, this web page. No advice or information provided by this website shall create any warranty. Reliance on such advice, information or the content of this web page is solely at your own risk, including without limitation any safety guidelines, resources or precautions, or any other information related to safety that may be available on or through this web page. The International Gem Society LLC disclaims any liability for injury, death or damages resulting from the use thereof.

The All-In-One Jewelry Making Solution At Your Fingertips

When you join the Ganoksin community, you get the tools you need to take your work to the next level.

Trusted Jewelry Making Information & Techniques

Sign up to receive the latest articles, techniques, and inspirations with our free newsletter.