Hans Appenzeller’s Elegant Designs

8 Minute Read

In April of 1983, a simple and relatively unpretentious store joined the ranks of the illustrious "boutiques" and other high-priced establishments lining the sidewalks of Madison Avenue on New York's fashionable upper east side. The store's interior is characterized by gray, neutral colors, unobtrusive display cases, lighting so discreet as hardly to be noticed; all serving as backdrop for several carefully selected jewelry creations, some vases and printed signs intended to explain the design principles applicable to each of the objects on display.

Appenzeller, the name on the store and on each of the pieces in it, is not a well known name in New York's high fashion circles; the store arrived without particular fanfare and seems determined by the almost laconic demeanor of its interior to let people discover for themselves who Appenzeller is and what he does. He is Hans Appenzeller, a Dutch designer specializing in jewelry, more particularly on incorporating the characteristics of industrial processes and the principles of industrial design into several types of finished, ornamental objects, especially jewelry.

After graduating from Amsterdam's Rietveld Academy in 1969, Appenzeller immediately opened a shop in collaboration with two partners. "We had what amounted to an already established clientele of young people who sympathized with our objectives, and who perceived themselves as part of a developing avant-garde," Appenzeller says. "Amsterdam was an exciting place in those days. News of something original would be carried throughout the city by word of mouth. People we had never heard of would show up on our doorstep with really quite wonderful designs, things that they wanted us to show. So we would show it."

Appenzeller and his partners were committed to exploring several new possibilities in jewelry design: first, that the fundamental properties of a material be made somehow manifest in the objects made from it; second, that the process of making the finished objects not be concealed, as is usually the case with jewelry; and third, that the materials selected be appropriate to the task in hand, allowing for the expression of the designer's technical proficiency as opposed to the object's display value. Appenzeller states the third principle succinctly, "We wished to assert the ascendance of taste over wealth."

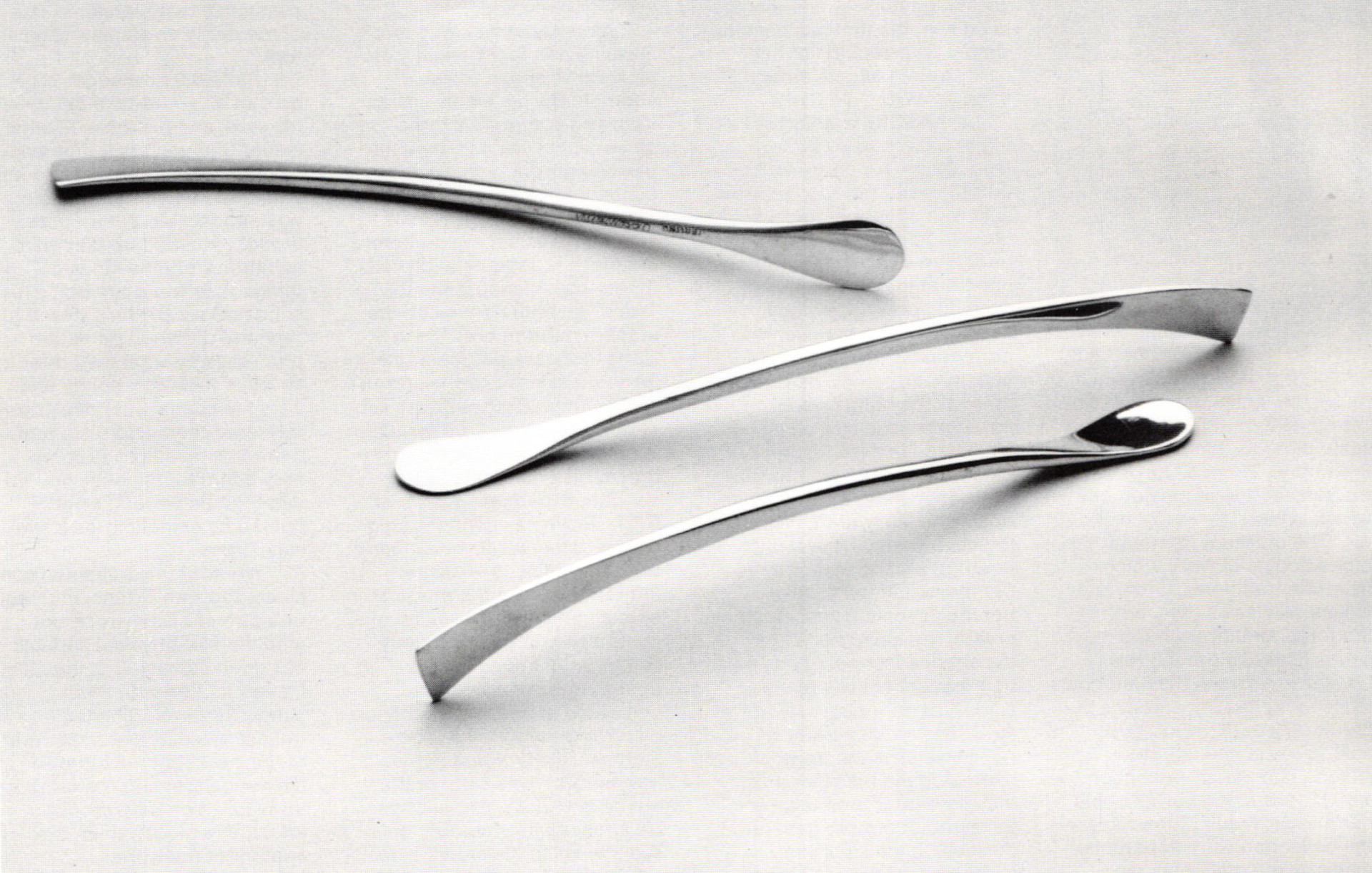

As one might expect, Appenzeller's own design principles are exemplary: he sees himself as working in a functional way to make what are essentially nonfunctional things. He groups the things into what he calls "collections": each collection being ruled by various self-imposed restrictions. Restrictions fall into several categories: characteristics of the material (rubber is elastic, plastic is transparent, gold is malleable); consequences of the technique (a metal grid, distorted by stamping, resembles a piece of fabric frozen into a given shape); uses of the finished object (method of closure functions as the determining factor for forms assumed by bracelets and necklaces).

In evaluating his own work, Appenzeller perceives the "elegance" of a given design as directly proportional to the challenge that his self-imposed restrictions present. Thus the folding bracelet of 1975 is seen as particularly successful because it uses an extremely simple principle to solve a problem indigenous to bracelets. In both intention and result, this piece shows how closely related Appenzeller's thinking is to that of industrial engineering and other disciplines where function takes precedence over esthetics. That functional and esthetic values can be made to merge, and that the resulting objects will have an intrinsic commercial appeal—this was the true challenge, and the determining factor in where Appenzeller finds himself today.

In 1975, moved by the gradual dwindling of exciting new work for display in collaboration with his partners, Appenzeller opened a jewelry gallery of his own in Amsterdam. He also showed some of his work in New York (at Amulets and Talismans) and Boston (at the Institute of Contemporary Art). He felt himself being drawn into other areas of design than jewelry: vases, dishes, lighting fixtures, even buttons. He investigated the possibility of mass producing some of his designs and learned to estimate the amount of personal supervision a manufacturing operation would take in order to preserve the esthetic integrity of a given piece. Still, in spite of his steadily increasing renown, he became more and more interested in opening a store in New York.

An exhibition at Artwear, a Soho gallery specializing in unusual jewelry, opened the door for the eventual establishment of Appenzeller's Madison Avenue store. Occurring in September, 1980, the Artwear show aroused enough interest in his work so that he could negotiate agreements with several "high-tech" stores in Manhattan to sell a line of vases and bowls, designed according to the golden section, which he was having manufactured in Holland- The bowls, made of spun, anodized aluminum, were sold signed and ranged in price up to $100. Enough customers bought them for Appenzeller to investigate seriously the idea of opening a store in New York.

This seemed like a rash decision at first. After all, what reasonable expectation of success could a jewelry designer have in a new market where whatever reputation he did have was built on vases and bowls? Appenzeller decided that good design is good design, and that if people will buy one well-designed object they will buy others. He reasoned further that his jewelry especially would only sell if it were displayed in an environment where customers could perceive what it was and, curiously enough, what it meant. And so, in spite of the necessity of still minding his own store in Amsterdam and supervising spun aluminum production in the Netherlands, Appenzeller appointed a business agent to find a site suitable for a store in New York within several clearly defined guidelines.

The store did not have to be large, but it had to be in the right place. Appenzeller instructed his agent to keep in mind who the jewelry would appeal to and what type of impression the store itself should create. Above all, the quality of the jewelry and the superiority of its design should never be subject to question. At the same time, the store should not be perceived as either pandering or condescending to the specific market selected. The diligence of Appenzeller's agent, Thom Van Kleef, was rewarded with success; a lease was signed in December, 1982, for commercial use of the ground floor at 820 Madison Avenue.

Renovation of the site, begun in January, was subject to the direct supervison or influence of Appenzeller himself, down to the fine details of lighting, colors and fixtures. The visual merchandising, if that is the proper term for an interior so sparsely arrayed, has still somehow managed to suggest a modicum of comfort and warmth. If one's first impression of the space is tinged with irritation at its minimalism, this changes to a form of respect for the designer's avoidance of gimmicks and new wave paraphernalia. After a time, the store's fixturization recedes into the background, serving simply as enhancement for the pieces on display. These are changed regularly to allow for a sort of eclectic review of Appenzeller's collections.

The collections are best described as exploratory clusters of objects developed through creative investigation of a limiting idea. For instance, the 1973 collection appears to be about the properties of rubber. Here we see a piece of rubber not unlike a section of inner tube enclosing a band of metal, which reveals its shape within. The rubber clings to the wearer's arm, thus holding the assemblage in place as a bracelet. Other pieces feature a thick rubber strap held in place within a notched aluminum ring, a perspex (translucent plastic) armband that is adjustable across the edges of two black rubber buttons, a bracelet of metal tubes laid side by side and connected transversely by a rubber thread, and a massive brushed aluminum circle held shut by a visible clasp of rubber.

Appenzeller's more recent work shows above all else a playful appreciation for the materials he has come to know so thoroughly. 1982's collection of woven jewelry investigates this type of item—as necklace and as bracelet in particular—so thoroughly that it seems unlikely that other designers would care to compete with him. We see woven brass, stainless steel, silver and gold in a bewildering variety of configurations. Other evidences of a mind at play emerge only after much observation: a simple gold bracelet attached at each end to a semicircular piece of plastic which skews this way and that to allow passage of the hand, bracelets of corian (plastic impregnated with an aluminum oxide additive) seeming heavy as lead next to their ordinary plastic counterparts, and a diamond ring which actually conceals the diamond: "I designed the setting in such a way as to make it a logical necessity for the diamond to be there," observes Appenzeller.

Appenzeller's jewelry, embodying as it does so many of the principles of industrial design and engineering, may yet be blurred in its public's perception because of the ubiquitous and ever more meaningless concept of "high-tech." This would be an injustice, because the core of Appenzeller's inspiration is elusive and resistant to categorization. Very few mass-produced objects are suitable for esthetic appreciation, and the ones that are seem to have got that way almost in spite of themselves. Appenzeller, by having a clear vision of what he wants his pieces to look like and by fabricating each piece to an extraordinary degree of finish, is intentionally striving to create the beautiful, mass-produced "design object" before it is mass-produced. He appears in many cases to have succeeded.

And from this an intriguing question arises: if these bracelets and necklaces were mass-produced, would they still be as beautiful as they are now?

Jabez L. Van Cleef writes about design, engineering and marketing for an industrial public relations firm in Manhattan.

You assume all responsibility and risk for the use of the safety resources available on or through this web page. The International Gem Society LLC does not assume any liability for the materials, information and opinions provided on, or available through, this web page. No advice or information provided by this website shall create any warranty. Reliance on such advice, information or the content of this web page is solely at your own risk, including without limitation any safety guidelines, resources or precautions, or any other information related to safety that may be available on or through this web page. The International Gem Society LLC disclaims any liability for injury, death or damages resulting from the use thereof.

The All-In-One Jewelry Making Solution At Your Fingertips

When you join the Ganoksin community, you get the tools you need to take your work to the next level.

Trusted Jewelry Making Information & Techniques

Sign up to receive the latest articles, techniques, and inspirations with our free newsletter.