A Conversation with Bjorn Weckstrom

7 Minute Read

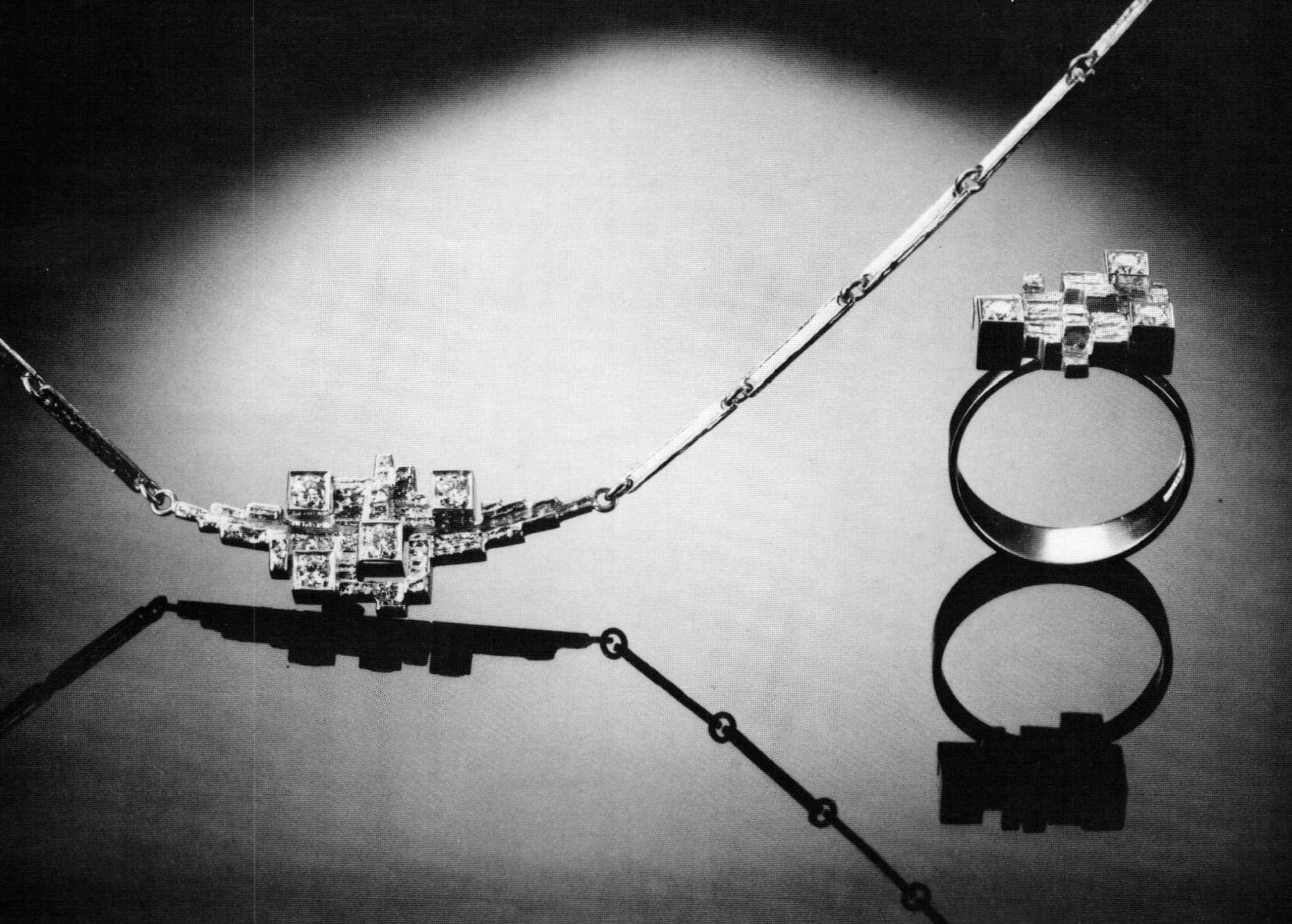

Björn Weckström, a Finnish designer who has enjoyed a virtually unparalleled opportunity in his native country, was the keynote speaker at the recent Society of North American Goldsmith's conference held in New York City. In an interview conducted before his talk, Weckström discussed his own unique position and his views of the jewelry world.

Because he has had a nearly 20-year long relationship with the Finnish jewelry company Lapponia, Weckström has had the luxury of being a house designer with very few restrictions. He has been, and remains, free to pursue other design areas such as glass, ceramics and furniture, always knowing that his work for Lapponia would give him a financial base. But this security is a double-edged sword; Lapponia demands that Weckström's new designs bear a strong family relationship to those that came before. Perhaps this restriction has been responsible for his curious lack of interest in what is going on in the rest of the jewelry world. And most peculiar, in light of his invitation to speak before this particular group, is his lack of awareness of the contemporary goldsmith's move to bridge the gap with the world of commercial jewelry.

Weckström's association with Lapponia began in the 1960s. It is a tribute to his vision that his sculptural designs look as contemporary today as they did 20 years ago. But that may also be a tribute to the Scandinavian customer who, he says, is open to new design. This is not true of the local Finnish retailer, however, who is very much like his American counterpart. In the beginning Weckström could not find, jewelry retailers who would carry his work. In order to break through. he opened his own retail shop in 1959 where he sold his own work as well as that of his colleagues.

Also influencing his thoughts on design in his move, two years ago, to Italy. Where he spends most of his time working on full-size sculptures. The move reflects one of the major problems of life in Finland—the lack of light in winter. At the height of winter, life is lived nearly in total darkness, with the sun crawling across the horizon for barely two hours a day. Working on sculpture one day, jewelry the next and glass or dinnerware the third is beneficial, he says. "Creativity increases with the number of media you are using."

Although not primarily concerned with jewelry today, Weckström has a clear sense of what jewelry is all about, why it exists and what it means for the customer. He sees jewelry's role in the contemporary scene as a kind of social signal. "It's pre-verbal communication. It's like clothes, it reveals our social attitudes, education level. It's practical, it cuts down time." And he sees in jewelry the shift in social attitudes from the 1960s to the present. "The 60s were very optimistic. Men were wearing open shirts with lots of chains. Then the energy crisis came and optimism went down. People were scared. Men were all closed up with ties. The situation changed totally, and in a very short time. We thought—'tomorrow won't be better.' Now, slowly, the optimism comes back."

But there are other factors influencing jewelry designs, he says. "It's hard to sell big diamonds now. Now people want to show that they have culture. Just to have money is not very smart anymore." This is another example of the way jewelry gives off social signals. Beyond this, Weckström notes that in countries where men have more influence, they buy diamonds for their women, to show they have money. Where women are more influential, then interesting design becomes more important, because the women have more to say about the jewelry they wear.

In addition to its role as a mirror of the level of optimism, Weckström also sees jewelry choices reflecting changes in lifestyle. "During the 1960s, people went home from work and changed clothes to dress up when they went out. The lifestyle changed very much after the 60s. People went right from the office to the party. Jewelry had to function all day and into the evening." In a purely design sense, Weckström sees everything as sculpture, and jewelry is a miniature version of that art form. "It functions with a human background instead of architecture and nature. I am a sculptor. Whatever I do, they are usually sculptures. The only restriction is that it has to function against a human body."

In Finland, as in the United States, there is a split between academic and practical teaching. Finland has a goldsmiths' school based on handicraft and an academy to produce metalsmiths. "l went to the goldsmiths' school; it was more practical." Still, he doesn't feel it makes that much difference. "No school is so bad that it can spoil a good designer." This same comment made during his address evoked laughter and applause.

His complaints about the restrictions placed on him both by Lapponia and by the social climate of Finland were less well received. He enjoys a unique success which he describes as a peculiar burden to bear. "In the Scandinavian countries, success is a very undemocratic thing, particularly commercial success. Artists think that the public cannot understand something and if they do, it cannot be good." However, he also complains about having to do similar designs all the time for Lapponia, because people want to be able to recognize the work when they come into the store. Of course it's difficult to have sympathy with this problem; if he doesn't want the security of Lapponia, he could simply not do those designs that he says chafe him so much. That work acts as a patron for the sculpture he is now devoted to, and he acknowledges that.

"For a designer, it's a great thing to have a corporation that can be the producer. He can make through that producer unique things too, things that he can use for promotion. He can experiment with metals and everybody benefits. The customer gets better things." There are hazards to working in both small companies and large, he says. "In a small company, everybody interferes with the design. In the large company, you have to force yourself into a style that is not yours. The design is too unrealistic and too difficult to produce.

His own early jewelry designs put too much emphasis on the sculptural aspect. "In Scandinavia 25 years ago, I was doing this silver jewelry that was very hard to wear. It was great looking in showcases but often a great disappointment when it was put on." Over the years, his pieces have become smaller. "The structure has become less pronounced. The size has become smaller because of the cost of materials as well as fashion. When I started, gold was just a pale reflection of silver designs. But gold has to have a totally new form of language, a new color, a new texture. I wanted to create a product that was as strong as possible. Gold is a very hot medium, full of passion and history."

This consistent way of thinking has kept some of his designs from the 1960s in production today. The secret he says, is that although the pieces are serially produced, they do not look it. "I really made it the way I wanted, without looking to see if it was salable. It became successful because it was so commercially unsalable. It looks very human—you don't have a feeling of a machine." Yet when he creates a new design now, he must think about it in terms of an edition of 500 pieces. And, he adds, "serial production is very brutal. The first model is very sensitive; in production, all the magic is gone."

One problem the Finnish designer does not have to face is that of jewelry theft—it just isn't a consideration for someone who might like to wear a big, showy gold piece. But the great emphasis on a truly democratic society in Finland eliminates the show-off customer. "People don't like wearing very showy jewelry. They try to be as modest as possible to be accepted."

The tremendous variety and quantity of new ideas in art that are available to the American designer, particularly in centers of activity such as New York, are a pleasure for him to see, but he offers a caution about them. "You show new things so quickly here. Every art movement breaks a new channel; everything that happens is welcome. But it's not necessary that it is permanent. You should be careful about putting up monuments to it."

Twenty-five years ago, Bjorn Weckström opened his own gallery in Helsinki. It has continued through the years, and today he sells his own sculpture, glass and jewelry there. It puts him into direct contact with the customer. "I learned a lot through that. I learned how underestimated the customer is—they are really you and me."

Ettagale Blauer is a jewelry writer and contributing jewelry design editor for Modern Jeweler.

You assume all responsibility and risk for the use of the safety resources available on or through this web page. The International Gem Society LLC does not assume any liability for the materials, information and opinions provided on, or available through, this web page. No advice or information provided by this website shall create any warranty. Reliance on such advice, information or the content of this web page is solely at your own risk, including without limitation any safety guidelines, resources or precautions, or any other information related to safety that may be available on or through this web page. The International Gem Society LLC disclaims any liability for injury, death or damages resulting from the use thereof.

The All-In-One Jewelry Making Solution At Your Fingertips

When you join the Ganoksin community, you get the tools you need to take your work to the next level.

Trusted Jewelry Making Information & Techniques

Sign up to receive the latest articles, techniques, and inspirations with our free newsletter.