Exhibition of Contemporary Japanese Metalwork

12 Minute Read

Quoting the scholar, Nyozekan Hasegawa, Masataka Ogawa Calls Japan the country of "the culture of hands." Over the centuries, no hands have been stronger or more skillful in carrying on the traditions of distinguished craftsmanship than those of the Japanese metalsmiths.

The origins of metalcraft are associated with the Yayoi period (300 B.C. - A.D. 300). During this time. metal objects—swords of bronze, mirrors, iron axes—were imported from the Continent to the islands; however, by the first century A.D., the imports were being duplicated by Japanese craftsmen. The native metalworkers also made bell-shaped bronzes called dôtaku, as well as personal ornaments and horse trappings. At that moment in history when the Byzantine Empire was boasting of the grandeurs of the newly completed Church of Hagia Sophia, Buddhism was introduced into Japan AD. (538-645). Buddhist shrines and temples displayed bronze figures of the Buddha and companion Bodhisattvas; incense burners, vases and other utensils, hammered from metal, were embellished with designs in repoussé or carved relief.

Cast bronze with inlaid silver, copper, shakudo, shibuichi

28 x 8 x 8 cm, 2250g

Temple bells were cast in bronze. The casting techniques were used to produce coins, government seals and cinerary urns. Many different metals were utilized by the Japanese; the term gokin refers to the five primary ones: gold, silver, copper, tin, iron. From these, various alloys were formed, for example, hakudô, "white bronze" resulting from a copper alloy with a high percentage of tin, shakudô, a "niellolike" copper alloy, and chûjaku sawari, a brasslike alloy of copper, tin and lead or silver (p.30). The Kamakura period (A.D. 1185-1392) replaced the patrician tastes of the Heian era (A.D. 794-1185) with the powerful presence of the warrior class. The samurai war lords recognized in the growth of the Zen Buddhist sect a stripping away of nonessentials which matched the simplicity of their own rugged lifestyle.

The popularity of Zen, fostered by the samurai, was further enhanced, in the Muromachi period (A.D. 1392-1573), by the introduction of the tea ceremony. Tea brought a new market for the metalcraftsmen to serve. The "way of tea" needed iron kettles, in which water could be boiled, metal trays and vases. To fill these needs, the Ashiya kettle manufacturing enterprise was initiated in Kyûshû and that of Temmyô was opened in the Kantô district (p.30). When the simple style of tea (wabi) was adopted during the Momoyama period (A.D. 1573-1615), kettles meeting the austere standards of the famous tea master, Sen No Rikyu, were made in the kama-za (kettle factory) at Sanjô in Kyoto (p.30). At the same time, swords and sword guards (tsuba) achieved a superior quality, as did the metal fittings made for architectural purposes. Metalwork was usually a family affair; trade secrets as well as proficiency in forging and casting were handed down from generation to generation.

Ichiro Kawahito, Sword Guard. Gold damascene on iron, 5 x 8 x 7.5 cm each, 100g.

Twentieth-century technology and methods of mass production threatened the continuity of family industries, and the skills of the craftsmen were gradually dying out. Although some earlier legal enactments had occurred to protect Japan's cultural heritage, it was not until 1950 that these were unified and brought under "The Law for Protection of Cultural Properties." Metal art was registered an Important Intangible Cultural Property in 1955. The protected areas in the field of metal design include metal casting, hammering metal, metal carving and surface treatments, such as gilding, coloring and polishing (pp.31-32). The best known and most respected artists in each aspect of metalwork were designated "Living National Treasures"; they receive an annual subsidy and the "responsibility for the refinements of techniques and the education of successors" (p.32).

The broad scope of metal art is represented in the pieces brought together in Kyoto Metal: an Exhibition of Contemporary Japanese Art Metalwork. The exhibition opened on March 4, 1983 at North Texas State University, which sponsored the assembly of examples of Kyoto metal art. The concept for the exhibition was formed in 1979 when Harlan W. Butt, a metalsmith and faculty member of the department of art at NTSU, visited Japan on a fellowship from the National Endowment for the Arts. His contacts with Kyoto artists in metal stimulated the idea of introducing Japanese metalwork, which has been known in this country primarily through the beauty and historical importance of swords and sword ornaments, to American craftsmen and the public. The plans for the exhibition were warmly supported by the Kyoto Metalworkers Cooperative Association, the City of Kyoto, the Texas Commission on the Arts, the National Endowment for the Arts and by North Texas State University at Denton. Three limitations were imposed to give unity to the 50 objects by 43 living craftsmen which were chosen for display in the United States: the medium was to be metal: the maximum dimension of a piece was not to exceed 60 cm; the metalworkers were to be residents of Kyoto.

Yoriaki Nakamura, Vase. Raised brass with shibuichi inlay, 19 x 22 x 22 cm, 1200g. Photos: Susan Touchstone

A first impression of the metalwork in the exhibition was triggered by the exquisite delicacy, the cool sheen of surfaces and the refinement of forms. Admirers of metalwork in this country are conditioned to expect High-Tech slickness or found objects imbedded in metal, the influences of Minimalism, a massive boldness suggested by the sculptor's use of the welding torch and sculptural overtones even in functional designs. In the objects by the Kyoto artists form is determined by function; a tea kettle is a tea kettle, a vase is a vase; a bowl is a bowl. There is another unexpected element. Western enthusiasm for Japanese art has often developed around an appreciation for the subdued beauty of the utensils of the tea ceremony and for the "folk-art" pottery style such as that embodied in the ceramics of the late Shoji Hamada. Such humble. often irregular, pieces are linked with that spirit of poverty, austerity and inevitability which is called shibusa.

Many of the metal designs by the Kyoto craftsmen direct attention to symmetrical perfection, glowing patinas, the enamel-like colors with their changing iridescences, and to feats of technical virtuosity. There are, however, in the exhibition some reticent pieces with tranquil monochromatic values which are not "captive to perfection." There is, for example, a handsome cast iron tea kettle by Jirôbe Takagi, a fourth generation ironworker. Not content to learn only the process of casting, Takagi studied under three painters and spent two years of apprenticeship under the direction of a metalsmith in order to learn hammering and engraving techniques.

It is the influence of the masters of brush drawing that appears to have lead Takagi to use painterly touches to enliven the sides of his kettles. On one side of the tea kettle, in the Kyoto exhibit, there is a motif of grass blades which recalls the bounding strokes which plunge over Shoji Hamada's pottery. On the other side, Takagi placed two "sweet fish" slipping through the water. During the finishing process, the kettle was roasted over a charcoal fire for several hours and coated with lacquer and ohaguro, a patina of black iron powder and vinegar. In contrast to the textured darkness of the kettle, the lid is a smoothly finished reddish brown; to it a silver knob was added.

Jirobe Takagi, Kettle. Cast iron, 23 x 17 x 17 cm, 2400g

Another restrained and unobtrusive piece is the Product of the fine craftsmanship of Yoriaki Nakamura, who also belongs to the fourth generation of a metalcrafting family. The vase is raised of brass with inlaid lines of shibuichi, an alloy of 25% silver and 75% copper.

Traditionalism is a constant factor in the metal art of the Kyoto craftsmen. Yasuyoshi Hasegawa is known for his Buddhist objects. He works directly in wax; the final product is cast in bronze using the "lost wax" method. He is represented in this exhibition by a bronze vase ornamented with raised coils, a Higo-zôgan spiral design called uzu. A respect for tradition is thoroughly absorbed in the sword guards (tsuba) made from iron with the ornament in damascene using gold exhibited by Ichiro Kawahito. Mr. Kawahito manages the Kawahito Zogan Company which has been in business for more than a century.

The making of bronze mirrors is a specialty of Shinji Yamamoto and his sons. At the age of 15, Shinji Yamamoto began to receive instruction in mirrormaking from his father. One of Yamamoto's traditional mirrors is shown here. It is of cast bronze with mercury amalgum. The design on the back is called the raft and chrysanthemum pattern. Nine years ago, the designs in metal by Shinji Yamamoto were designated Intangible Cultural Properties by the Japanese government. Mr. Yamamoto's son, Fujio, recreated for the exhibition an old Japanese mirror at Nara; its origin was carefully researched by Fujio and a professor at the University of Kyoto.

Today, in Japan, as in the past centuries, the skills of working with metal are transmitted from one generation to another by means of the apprenticeship system. In many instances, a young man will learn the craft under the guidance and supervision of his father or an older member of the family; others search out master craftsmen with established reputations. Harlan Butt observes that of the artists of the Kyoto group only three or four are first-generation metal workers. Many are fourth- or fifth-generation members of families of metal craftsmen; while one, Masahiko Satomura, belongs to the fourteenth generation of metal artists. Study with a master may last from one to 12 years, or even longer. Shumei Tanaka is a famous Kyoto teacher; at least seven of his students are included in the Kyoto exhibit.

Tanaka arranges for an apprentice to spend five years living in his home and helping him with his work in the studio. In addition to room and board, the student receives a small salary; in return, the apprentice must agree to remain for the designated time and he must promise not to marry. Throughout his years of service, the apprentice is required to work on the designs of his employer: however, he is given access to the studio after regular hours. Working until late at night, the student is free to develop his own designs. When the apprenticeship comes to an end, the newly trained craftsman may move back to his own home and open a shop of his own, or he may wish to continue to work for the master metal artist.

Another aspect of the metalwork of Japan which is foreign to the ideas held by students who graduate from universities in the United States is the Japanese willingness to carry on cooperative efforts with other craftsmen. Unlike his American counterpart, who will work on a piece from beginning to end, a Japanese artist may collaborate with a number of others in bringing a metal piece to completion. One craftsman may take the responsibility for casting the design, another may engrave or inlay the surface, while a third may be chosen to color the object with chemical patinas. Collaboration allows craftsmen to keep family trade secrets secure, at the same time, permitting others to profit by a particular expertise. A sense of community is also fostered among those who share similar interests. The spirit of cooperation is less difficult for people who do not make a virtue of an intense individualism. Japanese craftsmen have always held the belief that the functional values and esthetic character of an object transcend the identity of the person who made it.

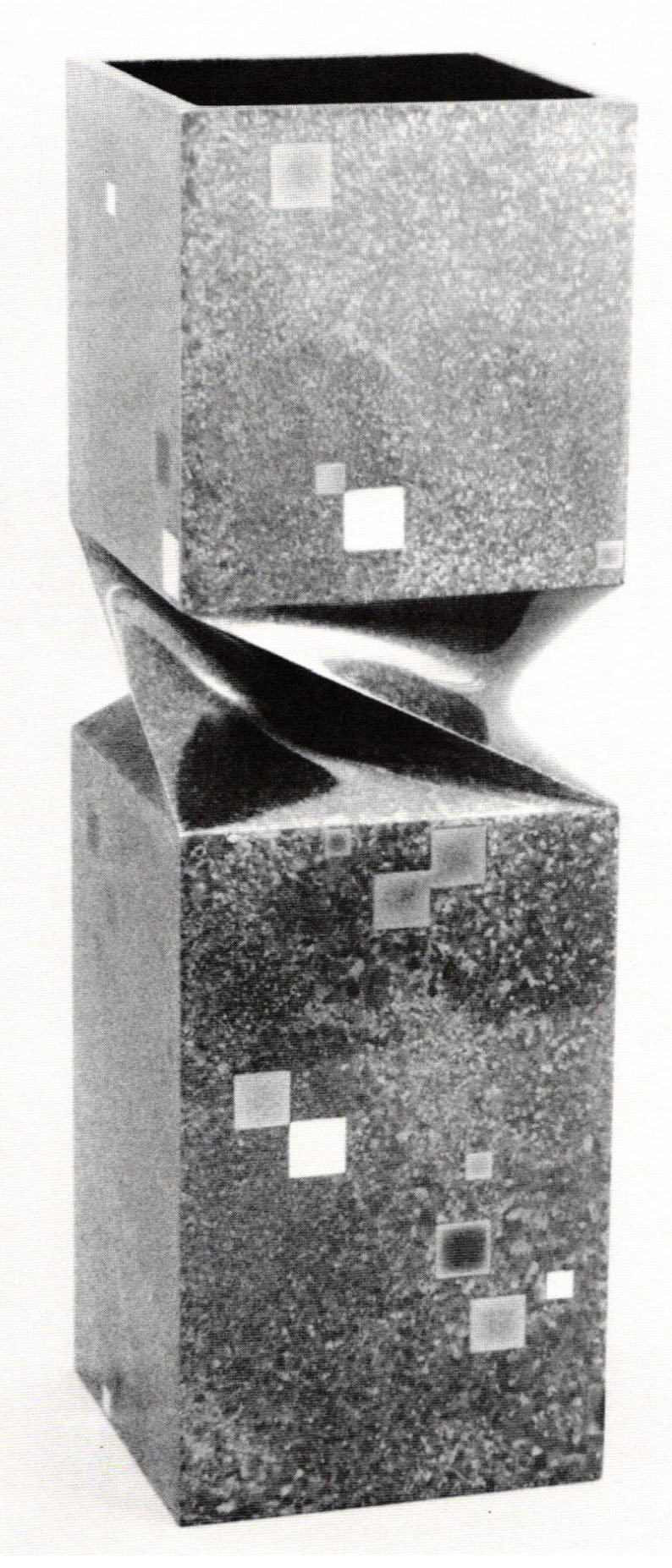

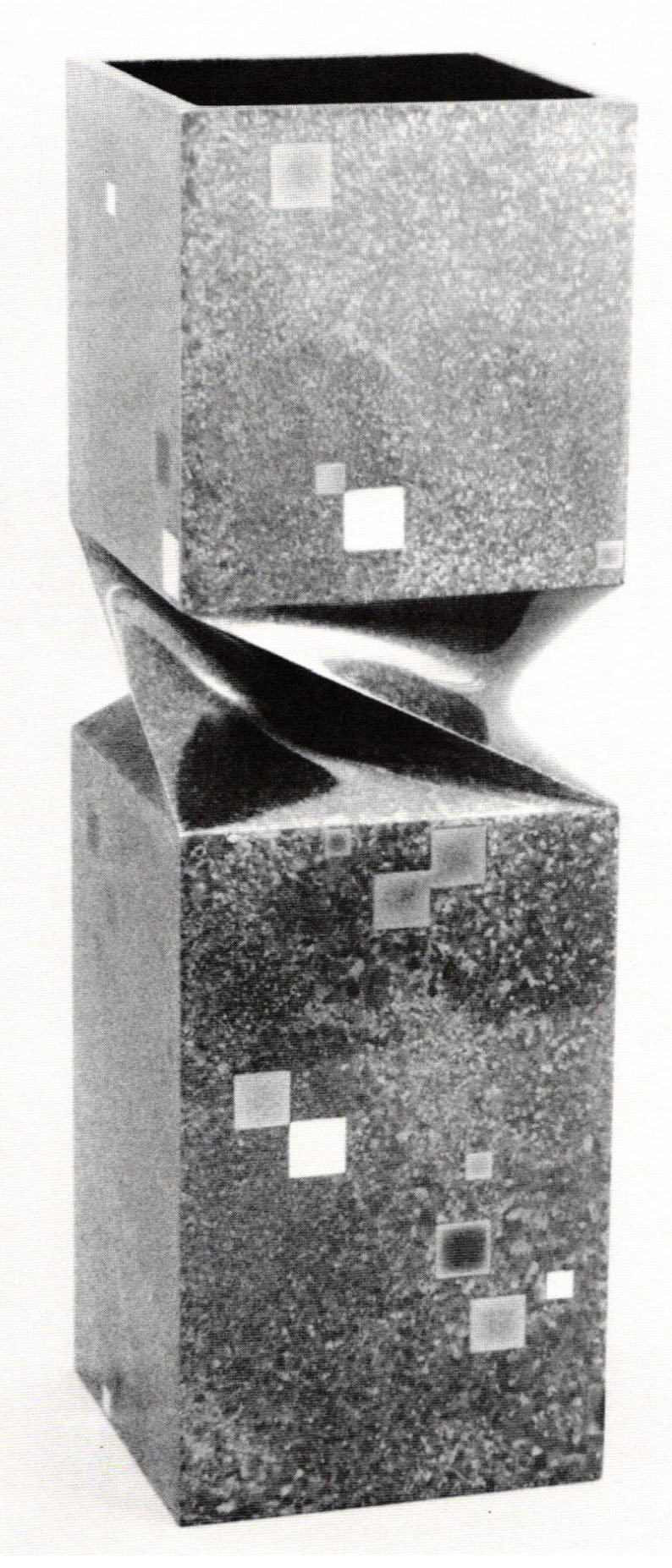

Traditionalism and an indebtedness to the past do not go unchallenged in the Kyoto Exhibition. Hideaki Yamamoto's cast brass vase, with inlays of silver, copper, shahudô, and, shibuichi, expresses the dignity of the past and contains an awareness of twentieth-century design. At first glance it could be a ceramic piece until the finesse of folded metal which separates the upper square from the lower rectangle becomes apparent. From some angles, the shadows seem to sever the upper portion of the vase from the bottom

Shinji Yamamoto, Mirror. Cast bronze with mercury amalgam, h. 3 cm, d. 27 cm, 3000g. Photos: Susan Touchstone

Eiji Yamamoto, a son of Shinji, exhibits a mirror which is given a new sense of dynamics by its maker. The cast bronze mirror is referred to as a "magic mirror." The mirror, which has bold calligraphic figures on the back, is held on curving brass brackets supported on a rough oblong tile. Opposite the mirror's face a second circle with a light cream-colored surface is mounted. Although the light was not properly channeled in the museum, Mr. Yamamoto, who was present at the opening of the exhibit, explained that the mirror holds the Japanese character for long life hidden in its interior. This can only be seen when the light is reflected off the mirrored surface onto the panel at the end of the tile mounting. The design is both sculptural and, in a sense, kinetic as the reaction to light brings about varied reflective qualities.

The catalog for the exhibition is harmonious and suitable in design, but the black-and-white-photographs cannot convey either the scale of the metal. work or the nuances of color which exist in the patinas of the metal surfaces.

The significance of "Kyoto Metal" lies in the link it establishes between craftsmen and the public of the East and West, and the opportunities that it opens for further exchanges between the two cultures. But it has an even deeper significance. An awareness of the apprenticeship system by which Japanese metalworkers learn their profession becomes a part of the dialogue begun by Mark Baldridge's editorial, in the fall 1982 issue of Metalsmith, in which he questioned the ability of university-trained metal craftsmen to apply their skills successfully in the marketplace. In the foreword to the catalog on "Kyoto Metal," Harlan Butt observed, "An interesting fact about the craftsmen in this exhibition is that they all support themselves by the creation of handmade metal objects."

This exhibit was reviewed at North Texas State University, Denton, Texas, where it was shown from March 5-31, 1983. It will travel across the United States in the next year, as follows: The University of Michigan, Ann Arbor, MI, May 14-June 20; The National Ornamental Metal Museum, Memphis, TN, June 30-August 10; Southern Illinois University, Carbondale, IL, August 17-September 18; Parsons School of Design, New York, NY, September 26-October 26; Japanese American Cultural and Community Center, Los Angeles, CA, November 7-December 10; Museum of History and Industry, Seattle, WA, January 18-March 11, 1984.

An illustrated catalog is available from: Harlan Butt, Department of Art, North Texas State University, Denton, TX 76203-5098 or at exhibition locations.

Notes

- Masataka Ogawa, The Enduring Crafts of Japan (New York/Tokyo: Walker/Weatherhill, 1968) "lntroduction," p. ix

- "Metalwork," Living National Treasures of Japan, Jan Fontein, ed. (Boston: Museum of Fine Arts, 1982), p.29-32

- Sôetsu Yanagi, The Unknown Craftsman (Tokyo: Kodansha International Ltd., 981), pp. 148-149

You assume all responsibility and risk for the use of the safety resources available on or through this web page. The International Gem Society LLC does not assume any liability for the materials, information and opinions provided on, or available through, this web page. No advice or information provided by this website shall create any warranty. Reliance on such advice, information or the content of this web page is solely at your own risk, including without limitation any safety guidelines, resources or precautions, or any other information related to safety that may be available on or through this web page. The International Gem Society LLC disclaims any liability for injury, death or damages resulting from the use thereof.

Related Articles

Production Jewelers: Design & Industrial Techniques

Safety Notes for Jewelers on Pitch, Chasing and Repousse

A Replica of the Sutton Hoo Sword

An Interview with Leila Tai

The All-In-One Jewelry Making Solution At Your Fingertips

When you join the Ganoksin community, you get the tools you need to take your work to the next level.

Trusted Jewelry Making Information & Techniques

Sign up to receive the latest articles, techniques, and inspirations with our free newsletter.