Ed Levin: 40 Years of Craft Jewelry

10 Minute Read

It is only within the past two decades that craft jewelry has become big business. From a marketing viewpoint, the movement, circa 1990, has come a long way since the likes of Sam Kramer, Ed Weiner, Art Smith and Paul Lobel intimidated, cajoled or otherwise charmed customers into buying their, then avant-garde, creations. But almost half a century after Lobel opened his studio/shop on West 4th Street in Greenwich Village, the business of selling studio jewelry is booming. And much of its success is due to the inspiration and know-how of Ed Levin. Levin, over four decades, has evolved a company that produces handmade jewelry cost-efficiently and in limited quantities. "His particular genius is that he made the transition from craftsman to manufacturer with little or no compromise in the freedom and spontaneity of design that is the mark of the craft product."

Ironically, the Ed Levin of the 1940s and 50s was a rather unlikely candidate to become a merchandising legend. Born in New York City on February 4, 1921, and brought up on Long Island, Levin dreamed of being an artist. To that end, he studied fine arts at Columbia University, sculpture with Chaim Gross, painting with Kurt Seligman and Paul Wieghardt, ceramics at Alfred University, perception and iconography at the New School and art analysis at the Barnes Foundation. But, now, in retrospect, he is proud to refer to himself as an iconoclast. Politically, he has always been a pacifist; he chose to be a conscientous objector during World War ll. He spent some of the war years working as an aerial photo forestry analyst, a machinist, an instrument assembler and a multilith operator. He was also a civil rights activist, involved with CORE at the very beginning of the movement for racial equality. In the early 1940s, Levin devoted some of his time to a ward for psychotic children in Chicago, and, in 1943, he cofounded a commune there, in a west-side slum.

After returning to New York in 1944, Levin taught art (including painting, ceramics, woodworking and pottery) hall-time at the New Lincoln School and crafts the other half of the time at the 110th Street Community Center in Harlem. Consequently, one of his legacies about which Levin is most proud is that over the last four decades (including those artisans working for him in Bennington, Vermont and Cambridge, New York), he has trained hundreds of people to make jewelry.

Ed Levin first became interested in jewelry in the late 1930s, when as a college student he sought something unusual as a gift for his mother. The work of a Cuban-American metalsmith, Francisco Rebajes was "the only thing modern in jewelry" that Levin could find. He purchased two brooches: a palette and a negroid head. The first pieces of jewelry that Levin himself made were done in 1942, while he was working as a machinist. They were stainless steel and silver rings that he turned on a lathe, also gifts for his mother. This experience with machinery taught him the skills necessary to understand tools, one of the essential agents in his jewelrymaking scheme. Levin's attitude towards tools is one of the factors that makes his jewelry unique; he designs the specific tools needed to accomplish each piece, thereby facilitating the craftsmanship and at the same time imbuing the jewelry, vis-à-vis its process, with an even more personal aspect than its design and fabrication alone could achieve.

After World War II, around 1947, Levin went with his parents to Buenos Aires, to visit his brother who was living there. He decided to remain in the Argentinian city for a while to paint, and in order to support himself, he went to work for one Señor Michi, a Florentine jeweler who worked in the Renaissance tradition. Señor Michi used no modern tools other than a polishing motor, and this hands-on production markedly influenced the neophyte Levin.

Upon his return to New York, about a year later, Levin became a fulltime craftsman, making jewelry and ceramics in the bedroom alcove of his railroad fat beneath what is now Lincoln Center. But, always having been a nature lover, Levin found the peace and inspiration of the country lacking in his life. Therefore, drawn by the rural beauty of Vermont, he moved, in 1953, to Shaftsbury, near the North Bennington town line, where, in an attic, he and his wife Ruth set up a jewelry studio. He worked with Ruth alone, until, in 1958, he hired an apprentice (Charles Thompson), who was to become the foreman of the Ed Levin Arts Workshop in Bennington Village in 1964.

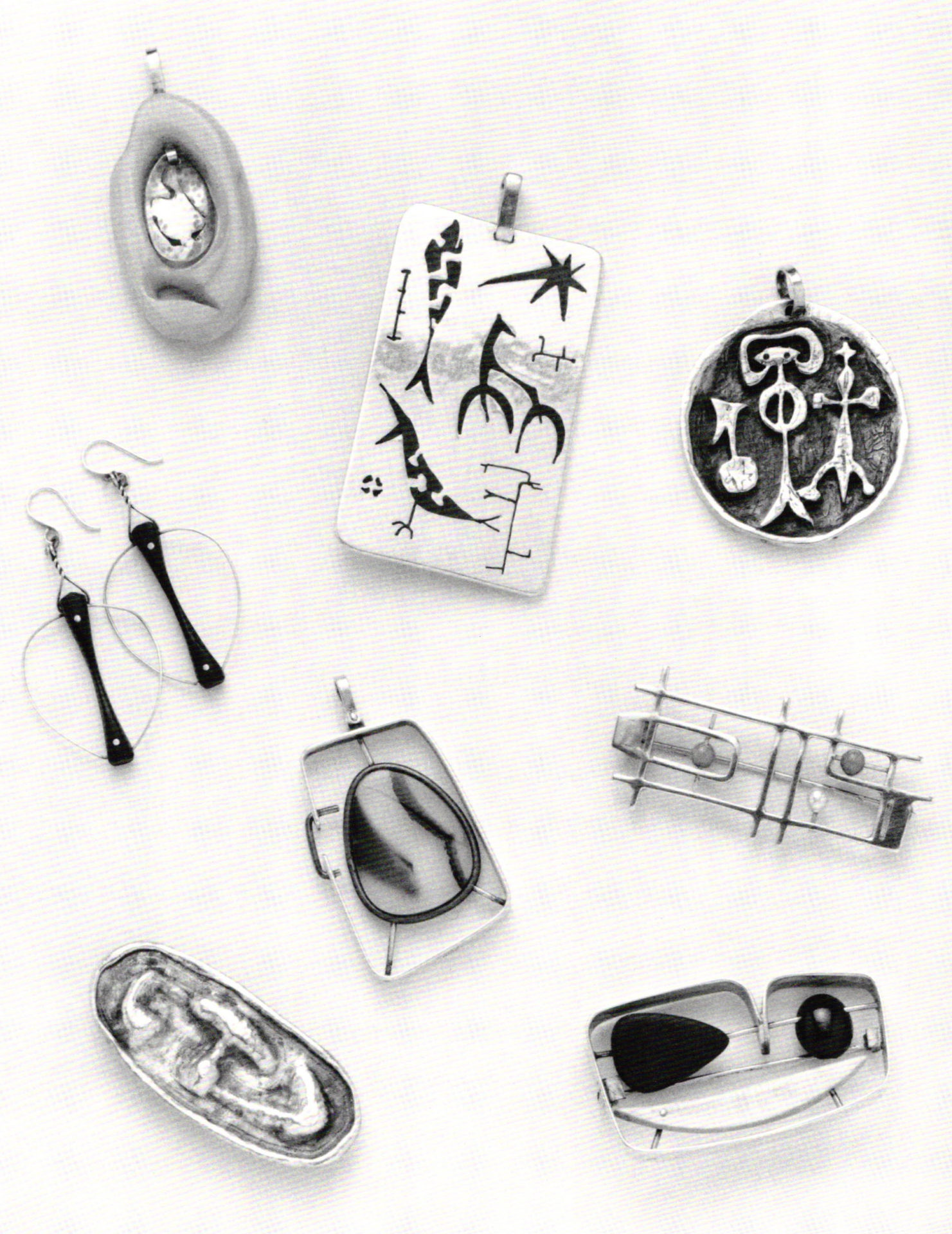

Alexander Calder's esthetic was admittedly the greatest influence on Ed Levin's jewelry in those early years; that and a passionate love for the ancient and tribal informed his designs. One of Levin's first and most successful pieces was the Fruit brooch from 1952. Exhibited in "Designer Craftsmen U.S.A. 1953" at the Brooklyn Museum, it stylistically typifies the era. The brooch is comprised of teardrop, crescent and bullet-shaped forms of ebony, amber and ivory, respectively, which have been pierced by silver wires attached to a surrounding silver frame. The configuration is reminiscent of the lines and shapes of a contemporaneous stabile by Calder of the whimsical images seen in paintings by Miro or Kandinsky, or in monotypes by Bertoia. The Dove pendant reminds one of Braque's mythologically inspired jewelry, while another brooch Egg Box Construction from 1958, recalls the paintings of Mondrian. It too utilizes openwork styling along with suspended forms; in this piece beads of pearl, coral and jade are speared through their centers and are thus linearly suspended. All in all, the jewelry from the 1950s is consistent with the work of Ed Wiener, Betty Cooke and Milton Cavagnaro, to name a few of Levin's peers on the East and West coasts.

Eventually, Levin began retailing from his out-of-the-way workshop. And, in 1964, he moved this operation to the more accessible town of Bennington Village, along the well-traveled tourist Route 7. Due to an increasing demand for its product, the Ed Levin Arts Workshop (as it was then named) grew to employ six artisans, including Charles Thompson. The company directed its operations to both wholesaling and retailing. At this juncture Levin himself curtailed his involvement in the actual fabrication of the jewelry, limiting his own production to special orders, complicated techniques, the creation of new designs and prototypes and the making and repairing of tools.

As mentioned, this last occupation, regarded by Levin as an art in itself had fascinated the jeweler since his days as a machinist. He views the process of jewelry making as a sort of symbiosis between specialized tools and the end product. But, although emphasis was (and still is) on a volume of production scaled to supply a burgeoning number of retail outlets, Levin demanded handmade quality. To this end he assigned one worker to be responsible for each piece, from start to finish. The apprentice would receive a "kit," which would include a model made by Levin and step-by step instructions detailing the entire procedure in sequential order. Each piece, upon completion would be inspected by Levin and approved before it could be sold. For this kind of operation to be successful, the designs used had to be simple.

Over the years, Levin has explored the concept of simplicity in a variety of styles: primitive (his all-time favorite), classical, medieval and "timeless." And simplicity, along with respect for nature, has guided Ed Levin jewelry design for 40 years. Exemplifying Levin's respect for nature, materials, as much as possible, have been left close to their original state. He chooses roughly tumbled, some precious stones or other organic materials - bits of ivory, wood, amber, etc. - cut into bold shapes. Levin avoids high polish on the metal, whenever possible (and resents it when the public is shown, through sales resistance, to desire it), preferring instead dull or roughly textured finishes because of their association with age and use.

Regardless of the style, though, Levin has consistently sought invention in how the jewelry is assembled and functions. Much of his inventiveness is found, for example, in the way the findings are integrated in to the overall design. In addition, Levin has consistently sought perfection in the materials utilized. His craftsmen draw their own wire, roll their own sheet and mix their own alloys, rendering the metal appropriate for properly functioning jewelry.

As the 1970s approached, Levin realized that the market for handcrafted Jewelry was increasing and that a sizable group of educated consumers was emerging. In 1973, he decided to address the manufacturing challenge by selling the retail business in Bennington and moving his operation to a promising wholesale facility in Cambridge, New York. His concept was to "[develop] controls and standards so that the design statement of the artist could be reproduced in quantity, cost-effectively, [and] without losing its spontaneity…Making a new piece of jewelry begins with a design concept and ends with a tangible product made by production artisans to precise specification within a strict budget." To achieve his goals, Levin developed a unique production operation similar to, but a bit more complicated than, the modus operandi employed a decade before in Bennington.

Levin, and others, draw several freehand sketches and create many rough models of each new design. These are then turned over to the production manager and then the design coordinator, who renders precise working diagrams and exact specifications as to tools and materials. A prototype is then made, which is often modified several times. After the prototype is accepted, a job card, which outlines step-by-step instructions, is written. This, along with materials specifications, time standards, patterns, templates, materials samples and examples of the piece at each stage of production comprises a sample box, which some of 14 artisans will receive.

In 1981, wanting to divest himself of the business aspects of the company, Levin delegated the running of Ed Levin Jewelry to 39-year-old businessman Tom Wagner. Wagner quickly computerized the firm and set to the task of increasing its accounts. To accomplish this, he took a booth twice a year at the JA (Jewelers of America) shows, and gradually built the base of operations outward by, among other devices, employing telemarketers who would offer samples of Ed Levin Jewelry to its most promising retailers. The company, at present, with a staff of 35, boasts annual sales are $1,500,000. And Ed Levin Jewelry is sold at 400 stores throughout the United States.

As far as Levin himself is concerned, he would like to reduce even more his own involvement in the business, devoting his time and energy solely to problem-solving, where special tools and production methods are needed, and leaving the day-to-day operations to others. He wants to be an artist again - to paint, sculpt and make pottery.

Ed Levin's designs, with the exception of some inspired examples from the 1950s and 1960s are, on the whole, dependent upon production necessities. But it is because of this very production that the prices can be kept reasonable and the jewelry made accessible to a large audience. With few exceptions, Ed Levin Jewelry is a substantial, well-engineered product the pieces have weight, the findings are successfully integrated into the overall design and the closures work easily. The jewelry is exceedingly wearable; it is comfortable and it complements all manner of attire. There is a need for this kind of basic, low-priced jewelry. And Ed Levin has set the standard for the many limited-production craft jewelers who have chosen to follow his able lead.

Notes

- James S. Howard, "Small Business as an Art Form," D & B Reports (March/April 1986) p. 34.

- From a conversation between Ed Levin and Toni Lesser Wolf on July 26, 1990.

- Howard, op cit., p. 34.

Toni Lesser Wolf is a jewelry historian, lecturer, curator and writer living in New York City.

You assume all responsibility and risk for the use of the safety resources available on or through this web page. The International Gem Society LLC does not assume any liability for the materials, information and opinions provided on, or available through, this web page. No advice or information provided by this website shall create any warranty. Reliance on such advice, information or the content of this web page is solely at your own risk, including without limitation any safety guidelines, resources or precautions, or any other information related to safety that may be available on or through this web page. The International Gem Society LLC disclaims any liability for injury, death or damages resulting from the use thereof.

The All-In-One Jewelry Making Solution At Your Fingertips

When you join the Ganoksin community, you get the tools you need to take your work to the next level.

Trusted Jewelry Making Information & Techniques

Sign up to receive the latest articles, techniques, and inspirations with our free newsletter.