Beads in Contemporary American Art

15 Minute Read

Throughout history, beads have been treated as valuable personal possessions. More than thirty-thousand years ago, Cro-Magnon man strung pierced bear and lion teeth into necklaces that were worn both as adornment and as an indication of social standing. Beads have been used for the embellishment of different types of ceremonial garments, such as anklets, headbands and headdresses. In many cultures, beads were symbolic of commonly held beliefs and ritual practices.

Numerous African tribes held beads in high esteem for their medicinal powers. In the Philippines, two beads placed in a cup symbolically represented the binding of man and woman in marriage, and in the Catholic religion, beads prompt a sequence of prayer worship. Beads were also used to barter for goods and as currency. As the writer Lois Sherr Dubin explains, "From the seventeenth to the nineteenth century Europeans exchanged glass beads for beaver pelts in North America, for spices in Indonesia, and for gold, ivory, and slaves in Africa." Although beads have lost many of their earlier associations and connotations, in Western culture they are, nevertheless, still familiar, even fashionable objects.

Beads, the primary material out of which the objects in Structure and Surface: Beads in Contemporary American Art have been created, have not traditionally been considered a line art material, despite their long history of use as decoration and adornment. However, many contemporary artists, particularly during this decade, have turned to beads to challenge esthetic boundaries. The reasons are diverse, yet the single most compelling motive for the use of nontraditional materials like beads seems to be the possibilities artists find that enable them to transcend traditional approaches to making art. Furthermore, especially in this age of the cheap, mass-produced simulation, the use of beads contests the conceptual boundaries that separate fine art and popular culture.

Among the innovative works included in Structure and Surface are the diminutive ritual fetish figures of Mimi Holmes and the opulent and tactile vessel forms of John Garrett. Joyce Scott sews brightly colored beads, newspaper clippings and photographs together to create bold, colorful neckpieces that explore contemporary street life, black music and feminist issues. Larry Fuente restores derelict cars and creates ornate decorative patterns on their surfaces by covering them with a spectacular range of beads, bangles, plastic flowers and found objects. Sherry Markovitz creates life-sized animals such as elk and deer out of papier mâché and covers them with a heavily encrusted surface of intensely colored beads, buttons, fabric scraps and shells. Arch Connelly creates dazzling sculptures by using faux pearls and jewels to cover forms such as an airplane, the prow of a boat, even leaf shapes. This range of works demonstrates that beads are indeed a potent and versatile material.

Several important historical precedents underlie contemporary artists' use of beads. The early twentieth-century development of collage, initially practiced by Cubists Georges Braque, Pablo Picasso and others, was a process whereby nonart materials were introduced into the art matrix. Most of the artists represented in the exhibition (Sherry Markovitz, Buster Cleveland, Robert Ebendorf and Joyce Scott, for example) use collage or variations of the process in many of their works.

The artists whose work is included in Structure and Surface also share formal and conceptual affinities with artists of the American Pop Art movement. The critical examination of American culture carried out by Pop artists like Jasper Johns and Andy Warhol included a study of the material excess of American culture in the 50s and 60s. Robert Rauschenberg's "combine paintings" of the mid- to late 1950s are particularly important for their suggestion of accumulation. They rescue quilted blankets, newsprint, signs, postcards and the like from their ordinary uses in daily life and preserve them in ways that parody the popular materialistic psyche of the times. By finding new uses for worn, discarded and expended materials, the "combine paintings" of Robert Rauschenberg and his contemporaries opened the door for many of the artists in Structure and Surface (Fuente, Cleveland, Ebendorf, Rhonda Zwillinger, Markovitz, Connelly and Harper, for example) because of the way these works attempted to "act in the gap between art and life."

In our technologically based society, many persons are attracted to objects that are tactile, sensuous and invite associations with everyday experience. The re-evaluation in the late 1960s of the esthetic merit of traditional crafts, such as woodworking, basket making, weaving and quilting as well as the work of folk and outsider artists, is an important result of this natural human predilection. Therefore, it should come as no surprise that mainstream artists are integrating both formal and stylistic attributes of traditional forms into their work. This direction may be seen as an attempt on the part of artists to reinvigorate the art object with ideas that reflect a broader social purpose.

Feminist art, which coalesced in the years around 1970 at the California Institute of the Arts in Valencia through the joint efforts of Judy Chicago and Miriam Schapiro, is particularly significant to a contemporary bead esthetic. In the early 1970s, Schapiro began using traditional craft materials and techniques, such as gluing or sewing geometric pieces of fabric to canvas in order to create her art. This practice, termed by Schapiro "femmage," played off the idea of "collage," because for centuries women had been practicing similar methods through traditional domestic crafts; for example, hooking, piecing, sewing and quilting. By using such traditional methods, femmage opened the door for artists like those represented in Structure and Surface to explore the expressive range of domestic materials.

The feminist art movement created new areas of artistic investigation for all artists. Because of the breakthrough in the 1970s, much attention was focused on the creative possibilities of fabric. Artists were attracted to its flatness, decorative pattern and sensuous surface. The resulting investigations gave impetus to a movement, primarily in painting, called "pattern and decoration." Among those individuals who pioneered the pattern crusade were Miriam Schapiro, Lucas Samaras, Kim MacConnel, Sam Gilliam, Alan Shields and Joyce Kozloff. This outgrowth of interest in the creative potential of pattern and the fusion of traditional feminist art practices is still a source of vital interest to many of the artists whose work is included in Structure and Surface.

Finally, the mechanical procedures that are associated with using beads, such as repetition and seriality, coupled with the idea that beads function as a unit or module, recalls both Minimal and Process art of the late 60s and 70s. Nearly two-thirds of the artists represented in Structure and Surface (John Garrett, Rhonda Zwillinger, William Harper, Joyce Scott, Sherry Markovitz, Robert Ebendorf, Larry Fuente and Mimi Holmes) explore the abstract and decorative possibilities that the use of pattern and seriality provide.

Artists of New York City's East Village neighborhood, who became active in the early 1980s, look to the culture of their immediate environment for inspiration. This sensibility parallels that of the Pop Art period, with one critical distinction. East Village artists trivialize and parody the sophisticated ideals of the avant-garde by undercutting the hermetic purity of the high modernist esthetic through an assimilation of elements of kitsch into their work. In contrast to the heroic scale and abstract formalism of much contemporary painting, works in Structure and Surface by Rhonda Zwillinger, Arch Connelly and Buster Cleveland are often figurative and/or small in scale. In addition, they incorporate an eclectic menu of pictorial modes - from Pop Art, graffiti and mass-media imagery to the self-conscious reconstruction of Neo-Expressionism, Surrealism and 1970s "bad" art. Their work is, as one critic describes it, "blatantly eclectic, cannibalistic, frequently quoting its sources directly, either in irony, nostalgia, fantasy or futility."

Because beads are such a ubiquitous and often devalued material, we frequently think of them as simply embellishment. Beads are used to create jewelry and to decorate handcrafted objects such as pillows, quilts or garments; therefore, they are seldom seen as carriers of intellectual content or esthetic value. However, the artists represented in this exhibition demonstrate that beads can be used to create sophisticated, provocative artworks. In addition, Structure and Surface is also an examination of the many formal adaptations of the material. For example, the multitude of colors available in beads allows for the creation of painterly effects.

Further, the optical effects that beads possess, including reflectivity, luminosity and opacity, are visual qualities similar to and at times even surpassing the visual qualities found in painting. This visual richness is evident in the work of Fuente, Connelly, Zwillinger, Markovitz and Cleveland. Because beads are three-dimensional, they can also be a sculptural medium. Some of the artists use this attribute to investigate three-dimensional forms of expression. In Joyce Scott's work, for example, thousands of beads are joined together to create individual figures that are then combined to complete a rich figurative tableau in the form of a neckpiece. The fabrication of individual beads becomes an opportunity for Suzan Rezac to explore the sculptural possibilities of abstract geometric form.

Artists Robert Ebendorf, Suzan Rezac and William Harper make their own beads from both precious and nonprecious materials. The impetus for creating beads ultimately can be linked to their past and current use as adornment. However, as the art historian Oppi Untracht explains, "Central to the Western cultural concept of jewelry as art is the idea that the work is the designer's product of self-expression, and therefore creative and unique." Even though the individual beads are extraordinary in and of themselves, they are combined to form wearable art. These artists use collage, assemblage and fabrication, processes traditionally associated with the fine art practices of painting and sculpture. Often these approaches are used in conjunction with metalwork techniques such as cloisonné enameling, lamination and Florentine surface finishing.

Most of the artists represented in Structure and Surface utilize commercially made beads just as other artists would use paint, bronze or wood. However, the choice of beads as a primary artistic material necessitates working methods different from those traditionally used to create paintings and sculpture. These artists use several different methods to attach beads to an armature and/or secure them to one another. Some employ individually hand-set beads with various synthetic adhesives like silicon caulk (Zwillinger), polymer-based substances like acrylic paint medium (Connelly), epoxy resins (Fuente) or adhesives such as 527 Bond Cement (Markovitz) or Elmer's Glue (Sparrow). The beads can be individually strung together with string and stitched to an armature (Holmes and Markovitz), or they may be strung and then glued to an armature (Markovitz). Joyce Scott eliminates the need for an internal armature altogether by using various structural stitches like the "peyote stitch," while John Garrett weaves them into materials such as copper wire.

Several artists represented in Structure and Surface use beads to create works of art chat ostensibly address formal, fine art considerations, such as the beauty of shape, color and surface. Yet, through their incorporation of inexpensive, mass-produced and common elements, these artists challenge traditional distinctions between the materials of line art and the materials of more popular art. Arch Connelly's Travel by Sea and Rhonda Zwillinger's Paramount take the "modernist's" interest in decoration and visual effect to a point which some may even consider "tacky" excess. The exaggeration of formal properties and the reference to traditional subjects, such as a voyage or a romantic landscape, juxtaposed with the "kitschy" qualities of dimestore materials, challenge the artificial and limiting strictures of modernist canons. This confrontation causes the viewer to question the esthetic values and distinctions of our contemporary culture.

Joyce Scott, Sherry Markovitz and Mimi Holmes also address a spectrum of sociocultural concerns related to contemporary street life, nature and the environment. Their work recalls women's domestic handwork, crafts and wearable art forms. References are also made to both the forms and practices of divergent ethnic groups such as the Native American, Afro-American, Muslim and Hindu cultures and to difficult issues such as racism, inequality and death.

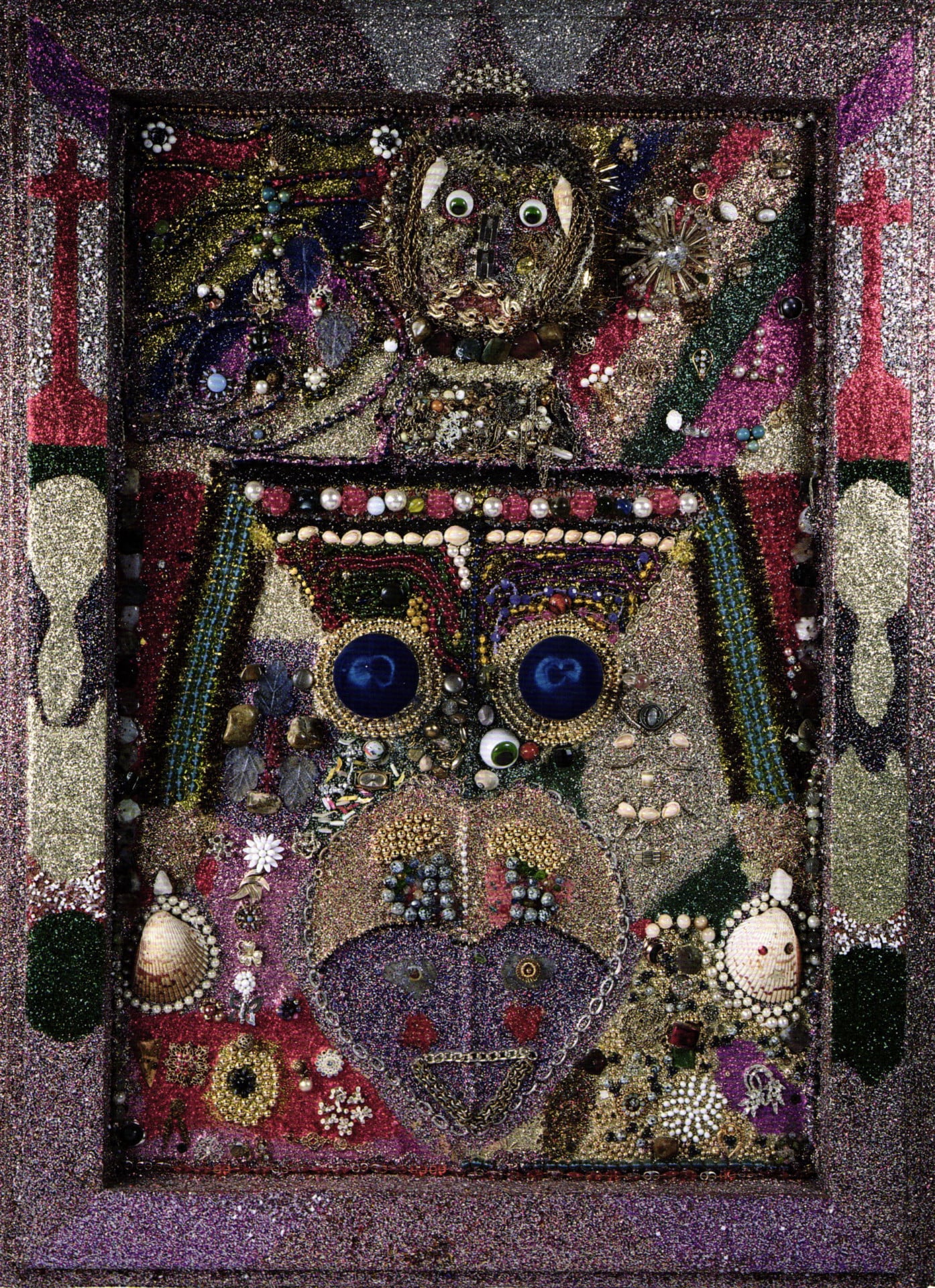

Simon Sparrow and Larry Fuente create works that show a preoccupation with the obsession and accumulation of the detritus of popular culture. Beads and other modular objects like buttons, watches, medals, yo-yos, Scrabble tiles and nail-polish bottles replete with nail polish are heaped into dense and, at first glance, casual agglomerations. These creations, less ironic and cynical than the works created by the East Village artists represented in Structure and Surface, seem to be direct expressions of an artistic vision that celebrates the glitz and surface of contemporary artifacts. Sparrow and Fuente use these ubiquitous and readily available objects out of their curiosity and affection for popular yet eccentric materials.

Twentieth-century artists increasingly have questioned the rigid complacency that has pervaded the long tradition of academic painting and sculpture. Even though this is so, there are those who argue that using materials and procedural methods that deviate from established practices for making art undermines and diminishes the esthetic merit and cultural significance of the object. Although beads, throughout their history, have been used as ornament or for decorative purposes, today's artists use beads as a primary material to create exquisite, conceptually rich wearable art forms, dynamic sculpture and assemblage. The material's varied formal properties - shape, color, transparency, luminosity, reflectivity and physical presence - bear comparison to traditional art materials like paint. The integration of multiple forms of artistic practice in regard to beads - folk art, decorative art, outsider art and feminist art - references many different aspects of our complex culture.

Some theorists contend that "high art" has become unimportant and does not reflect the interest or concerns of contemporary culture. However, Structure and Surface: Beads in Contemporary American Art exemplifies an evolving phenomenon in which artists are investigating the art object's function and social purpose in American culture. It also suggests that "high art" can both reflect and critique the preoccupations of contemporary society. The works produced by the artists in this exhibition manifest a personal, handmade and physical presence. Ironically, all of this is possible at a time when industry and technology continue to separate and sometimes alienate the individual from direct physical experiences. The works in Structure and Surface: Beads in Contemporary American Art provide both a critical and sensuous examination of alternative materials and processes.

Simon Sparrow's imagery is flat, frontal and hierarchal; i.e., the images are positioned within the frame based on meaning and significance. These characteristics recall much of the religious art from the Middle Ages and particularly Renaissance icons that were used in religious ceremony.

In Night in the City Joyce Scott evokes the tension of urban life by collaging the photograph of a dark alley into the neckpiece. The artist also explores the issue of rape. Multiple unclothed figures are imprisoned in a tangle of webbing, and a white female torso is covered with yellow hand prints, symbolic of violation. The irony of Scott's art is that it is beautiful, thereby fulfilling its function as adornment, yet its content undermines our expectation for the object to perform a singular task - decoration.

Suzanne Rezac's interest in surface and form is demonstrated by her imaginative and skillful treatment of precious metals like gold and silver. Her sculptural vocabulary in metals consists of geometric forms - circles, spheres, lozenges or squares - and the properties that the metals possess - purity, surface, grain, lustre, weight, smoothness and temperature. Rezac may manipulate the purity of gold in a bead in the same way a painter would use the intensity or value of color to delineate shape and form. This concept can be enhanced by using the warmth of gold in contrast with the coolness of silver or other metals. Ironically, by keying on the simple, intrinsic properties of her materials, Rezac finds infinite creative possibilities.

During the past decade many artists have sought to erase the boundaries between traditional women's crafts and painting and sculpture. Sherry Markovitz uses the detail and handwork so typical of women's crafts to create rich, encrusted surfaces and exciting visual patterns on her sculptures.

The beads Rhonda Zwillinger uses are brash, even gaudy. They are cheap, common materials; however, Zwillinger uses their color, shape and texture with the confidence of a painter who understands color theory. She hand sets most of the individual and strung beads and jewels in silicon. This process affords her the opportunity to work like a painter, experimenting with different colors, shapes and sizes to achieve the desired surface and optical effects. In pieces like Sentinel: Shaman, Zwillinger uses the beads and jewels to reinvest furniture and possessions that are no longer inherently valuable or serve a useful purpose with special, even magical, qualities. The stunning color combinations and heavily encrusted, sparkling surfaces animate these possessions. Through this transfiguration, they become meaningful again.

Joyce Scott's neckpieces incorporate an array of beaded figures whose caricature quality makes it easy to overlook content. For example, Dressing for Him portrays the stereotypic role of the seductive, Venuslike sex object in which women sometimes fine themselves caught.

Notes

- Lois Sherr Dubin, The History of Beads, from 30,000 B.C. to the Present (New York: Harry N. Abrams, Inc., Publishers, 1987): 17.

- Irving Sandler, "Tenth Street Then and Now," The East Village Scene (Philadelphia: Institute of Contemporary Art, University of Pennsylvania, 1984): 16-17.

- Oppi Untracht, Masterworks of Contemporary American Jewelry: Sources and Concepts exhibition catalogue (London: Victoria and Albert Museum, 1985): 7.

This article is part of the introduction to the catalog Structure and Surface: Beads in Contemporary American Art, an exhibition developed by the John Michael Kohler Arts Center, and mounted there from December 4, 1988 to February 12, 1989. For information about the catalog contact JMKAC, 608 New York Avenue, P.O. Box 489, Sheboygan, WI 53082-0489; telephone (414) 458-6144.

Thanks to Ruth Kohler, Director, JMKAC, for her help and cooperation with the realization of this article in Metalsmith.

Mark Richard Leach is Associate Curator of Exhibitions at the John Michael Kobler Arts Center.

You assume all responsibility and risk for the use of the safety resources available on or through this web page. The International Gem Society LLC does not assume any liability for the materials, information and opinions provided on, or available through, this web page. No advice or information provided by this website shall create any warranty. Reliance on such advice, information or the content of this web page is solely at your own risk, including without limitation any safety guidelines, resources or precautions, or any other information related to safety that may be available on or through this web page. The International Gem Society LLC disclaims any liability for injury, death or damages resulting from the use thereof.

The All-In-One Jewelry Making Solution At Your Fingertips

When you join the Ganoksin community, you get the tools you need to take your work to the next level.

Trusted Jewelry Making Information & Techniques

Sign up to receive the latest articles, techniques, and inspirations with our free newsletter.