The Bauhaus Metal Workshop, 1919-1927

16 Minute Read

In this article Deborah Norton traces the rise and fall of this seminal 20th-century school. Although Bauhaus policy revolved around personalities and philosophies, it nonetheless embarked on an influential experiment of incorporating the principles of art with the economies and practicalities of design.

When architect Walter Gropius founded the Bauhaus in 1919, he hoped to revitalize design by uniting the innovative vision of the fine artist with the technical ability of the craftworker. In formulating his ideas, he was influenced by famous workshop precedents, including that of William Morris, leader of the British Arts and Crafts Movement, and the Deutscher Werkbund.

In 1907, the Deutscher Werkbund was founded in Munich, a society of manufacturers, architects and craftsmen dedicated to raising standards of designs for industry. Gropius, a member of the Werkbund, in explaining the need for artists to become involved with industry wrote, "An object of even technical perfection must be imbued with spiritual content and with form so that it becomes outstanding in the multitude of similar objects."

Following World War I Gropius was appointed head of a newly combined art academy and arts and crafts school in Weimar which he renamed Staaliche Bauhaus. This new post gave him the opportunity to put his ideas into effect. In the Founding Manifesto, using medieval references worthy of a disciple of William Morris, he wrote: "Let us create a new guild of craftsmen, without the class distinctions which raise an arrogant barrier between craftsman and artist." He planned to unite all the creative arts under the primacy of architecture. He envisioned a team of men (and surely women, as one-third of the students were female) who would work independently, although in close cooperation to further a common cause, as craftsmen in medieval times worked together to build cathedrals. To Gropius, architecture was the culmination of all the crafts, so it followed that architects must undergo craft training before they could begin to design buildings. He told students: "All great works of in past ages sprang from absolute mastery of the crafts."

At the Bauhaus, curriculum was devised that would eliminate what Gropius saw as the two gravest faults of traditional art academies—slavish copying of historic styles and dependence on individualistic personal taste. All students took an initial six-month preliminary course, followed by a three-year training program in a craft workshop. Only after completion of the workshop training would a student be qualified to take the architectural course, which was not formally taught at the Bauhaus until several years later.

Because of the previous separation between art and crafts, Gropius found it necessary to hire two masters for each workshop, a technician to teach craftsmanship and a fine artist to teach form. As he explained, "The sensibility of the artist must be combined with the knowledge of the technician to create new forms in architecture and design."

Although idealistic philosophies and new approaches to art education played a significant role at the Bauhaus, it was the faculty that enabled the school to make such a unique and lasting contribution to 20th-century design by bringing together some of the most creative individuals of the time—men like Johannes Itten, Lyonel Feininger, Oskar Schlemmer, Paul Klee, Vassily Kandinsky, Lazio Moholy-Nagy, Josef Albers, Marcel Breuer and Ludwig Miles van der Rohe.

One of the first hired, Itten, a fine artist teaching in Vienna, developed and taught the preliminary course and was appointed form master of the ill-equipped metal workshop. Itten believed that art should be the expression of personal vision and emotion communicated through geometric forms. To Itten, these forms were historically and conceptually primary in the creation of art.

The early products of Itten's metal shop (1919-21) were direct extensions of the explorations of geometric forms from his preliminary course. Spheres, cubes, cylinders, and cones—or segments of them—became the basis for objects. Contrast, also stressed in the preliminary course, was achieved by juxtaposing opposite forms, such as circles next to squares. Ornamentation, always geometric, played an important role in these early pieces, giving personal expression to otherwise austere shapes. A container by Lipovec made in 1921 is typical of this period. Here the lid of a rectangular box is surmounted by the top half of a sphere. Surface ornamentation takes the form of circles applied in horizontal, parallel lines.

Metalwork produced after 1921 showed a change in style. At this time there was a general tendency in modern art to move away from an emphasis on overall compositional rhythms to a greater concern with the articulation of individual forms. This change is apparent in the work of Itten and his students. Pieces from this period are constructed element by element in an architectonic manner. In one anonymous teapot a truncated cone serves as the foot, with a sphere for the body and another cone for the lid. A whimsically shaped handle is the only ornamentation.

Finding a qualified craft master to complement the form master at the metalshop proved to be a problem. The first two hired, Willy Schabbon and Alfred Kopka, lasted only a short time. It was not until Christian Dell was hired in 1922 that this workshop was able to achieve some stability. Unfortunately, little is known about Dell, for despite Gropius's efforts to break down the barriers between artists and craftsmen, historian have written volumes about form masters while largely ignoring the craft masters. It is known that Dell was an experienced silversmith and a gifted teacher. Prior to the War he was at the Wiener Werkstatte in Vienna, producing holloware in an avant-garde, geometric style. At the Bauhaus Dell's work, devoid of decoration, concentrated on the innovative use of geometric forms. Coincidental with his arrival, surface ornamentation in the metal shop was abandoned. Historian Hans Wingler gives Dell little credit for this or any other change, stating: "The efforts to arrive at uncompromisingly new forms emanated from the artists, both teachers and students; the master craftsman, coming from a different to them.

Towards the end of 1922 Gropius adopted a new slogan, "art and technology, the new unity" which signaled a change in the Bauhaus focus.

Although the slogan was new it was consistent with ideas Gropius had espoused while a member of the Deutscher Werkbund. Perhaps he had sidelined these ideas in the early Bauhaus years in favor of teaching hand craftsmanship because he felt that only when the latter was mastered would a student be capable of creating high-quality industrial designs. It is unlikely tht he ever envisioned hand craftsmanship as an end in itself.

Efforts would now be devoted to designing for industry. Not all the masters felt comfortable with this new direction. Itten's ideal of creating individual objects imbued with personal expression could not be reconciled with designing for machines and he resigned.

To replace Itten, Gropius hired Laszlo Moholy-Nagy. As Moholy had no experience in designing for industry, initially he could only encourage innovative work that extended Dell's teachings. Moholy brought with him a belief in Constructivist philosophy, which emanated from the Russian avant-garde and Dutch De Stijl movements. The stress on formal precision, objectivity on formal precision, objectivity and rationalism would eventually prove to be highly compatible with machine production. Although this philosophy was in direct opposition to Itten's belief in self-expression, Moholy's commitment to geometric forms was as intense as his predecessor's. Years after the Bauhaus closed, a design by a former student that used a non-geometric curve, elicited this response from Moholy: "Wagenfeld, how can you betray the Bauhaus like this? We have fought for simple, basic shapes, cylinder, cube, cone and there you are making soft forms—which is dead against everything we have always been after."

As an artist Moholy was interested in exploring spatial design, which he defined as the "interweaving of shapes: shapes which are ordered into certain well defined, if invisible space relationships; shapes which represent the fluctuating play of tension and forces. He was also concerned with balance and weight displacement. These concepts appear in his students' holloware, which share certain characteristics: Their geometric forms create profile that clearly define the space they occupy; each element is conceived as a distinct part, yet the relationship of one to the next is equally important; and contrasting shapes and materials create tensions that are resolved by close attention to proportion and balance. Whether Dell shared Moholy's concerns and equally influenced the students is impossible to say.

In a particularly fine German silver coffeepot by Wilhelm Wagenfeld made in 1923-24, a spherical body is placed on a small cylindrical foot. This same cylindrical shape reappears as the neck and is topped by a hemisphere for the lid. A strong profile, contrasting forms and balance achieved by centering the weight makes this piece typical of holloware produced under Moholy and Dell.

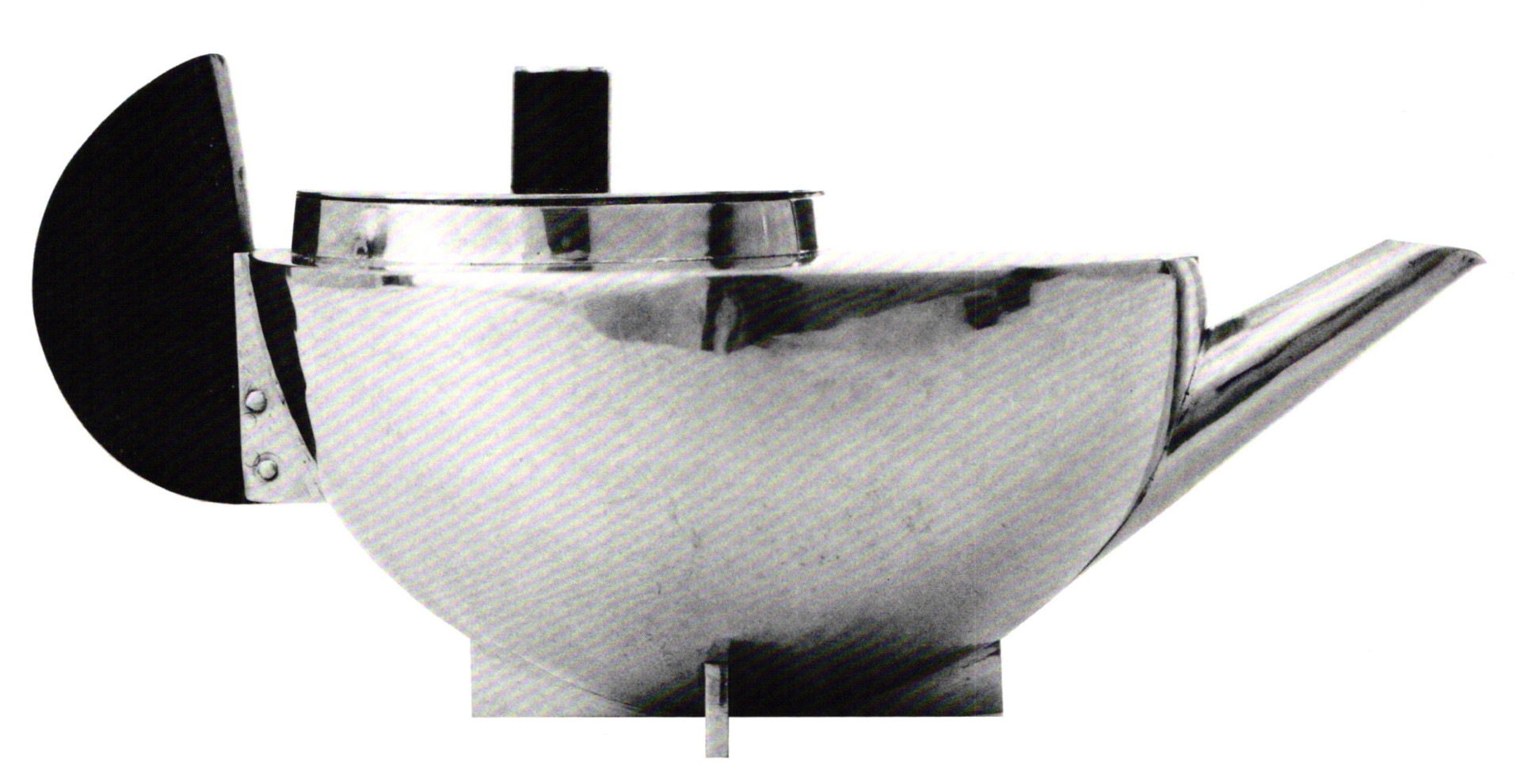

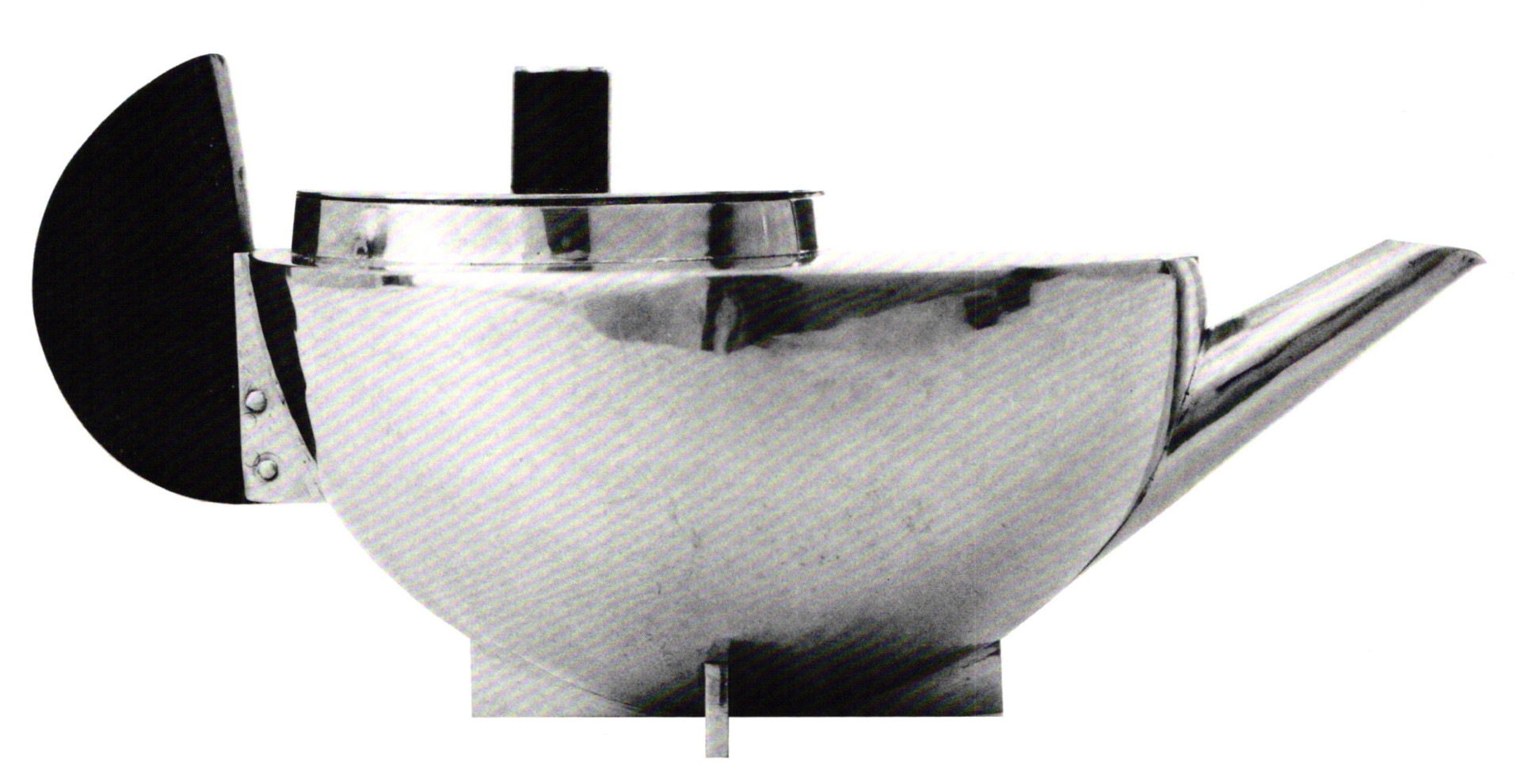

In the same time period student Marianne Brandt made a small teapot that also uses a sphere for the body. But unlike Wagenfeld's piece, where the circular shape is truncated at the foot and lid, her pot retains the pure sphere. However, this necessitated a unique solution for the appendages. The lid is made from an oblique slice cut out of the top of the sphere. The foot is composed of two thick strips of silver crossed at right angles, with the spherical shape of the body cut into the tops of the strips so the pot can nest securely without visually interrupting the sphere. The flat half disc that is the handle contrasts with the rest of the piece. Brandt also made a series of teapots using the bottom half of a sphere as the body. The lid is a thick disc placed towards the edge of the flat top surface. Although this seems to shift the weight off-center, Brandt's fine sense of proportion ensures that the pot maintains a visual balance. Contrast is heightened by combining various materials; she often used bronze for the body and lid, and silver for the foot, spout and handle mount. The handle itself was ebony. It is noteworthy that in all these handmade Bauhause pots the precision of the rigid geometric forms could have been machine produced.

Functionalism, a fundamental tenet of the Bauhaus, was also of importance to Moholy. Brandt has stated that everything was tested before it left the workshop—teapots had to be well balanced, pour properly and not drip. Yet, surprisingly, the solutions for handles, while visually exciting, were often functionally dubious. The small, solid ebony handles on Brandt's teapots seem difficult to grip. Several students' use of a sweeping arc, made of a flat piece of metal imaginatively combined with a right angle, appears functionally, awkward. The same can be said of a gravy pitcher by Wagenfeld that was designed to be gripped by two small wooden stubs emerging from opposite sides.

Although no actual designing for industry occurred during Moholy's first years at the Bauhaus, he encouraged students to experiment with handmade designs that might serve as prototypes for machine production. Because in his own art Moholy was obsessed with light, the metal workshop students turned to designing light fixtures. To Moholy there was no esthetic difference between a fine lamp and a fine kinetic light sculpture, for they were both conceived as carriers of light. The students' first attempts, although failures, were nonetheless a significant step toward uniting art and industry. Moholy has said, "I remember the first lighting fixture by K. Juckler . . . with devices for pushing and pulling heavy strips and rods if iron and brass, looking more like a dinosaur than a functional object. But even that was a great victory for it meant a new beginning.

Inspired by Moholy's abstractions in glass and metal, Wagenfeld and Jucker designed a table lamp in 1924. Moholy and Gropius, impressed by the prototype, decided that a series of lamps should be made for exhibition at the Leipzig Fair. So, in a primitive workshop, with only one ancient polishing machine, the metalsmiths set to work. Unfortunately, the results proved unsuccessful. Wagenfeld wrote, "Retailers and manufacturers laughed at our efforts. These designs which looked as though they could be made inexpensively by machine techniques, were, in fact, extremely costly craft designs." Years later Wagenfeld realized that his lamp was a "crippled, bloodless picture in glass and metal." Ironically, this same lamp design is being produced today by an English manufacturer.

In 1925 the Bauhaus was forced to relocate in Dessau for political reasons. This move gave Gropius the opportunity he needed to reorganize the school in order to fully implement his idea of uniting "art and technology." He asked Moholy to convert the metal workshop into a laboratory dedicated to the research and production of prototypes for industry. At first, many of the students objected Moholy later recalled, "Changing the policy of this workshop involved a revolution, for in their pride the goldsmiths and silversmiths avoided the use of ferrous metals, nickel and chromium plating and abhorred the idea of making models for electrical appliances or lighting fixtures." But eventually, probably as a result of Moholy's strong personality and his genuine commitment to the new goal, the students adjusted. Brandt commented on this transitional period. "At the time I was convinced that an object had to be functional and beautiful because of its materials. But I later came to the conclusion that the artist provides the final effect."

The preliminary course was maintained, but the system of dual masters was abolished as there were now Bauhaus graduates who could teach both craft and form. At this point Dell left. Whether this was because his services were no longer needed now that each workshop had only one master, or for other reasons, is unknown.

In Dessau function truly became the prime concern of the Bauhaus. Whereas before it was felt that the form must prove to be functional, now it was declared that the function must dictate the form. Despite the changes, the role of the fine artists remained as important as ever. Gropius felt that although function was dependent on science and technology, only artists could teach form. To Moholy the distinctions between art, craft, design and technology were irrelevant in the industrial age. "The criterion should not be 'art' or 'not art'." He said, "but whether the right form was given to the stated function."

In the new, well-equipped metal shop in Dessau light fixtures became the main focus, although some holloware production continued. The students' efforts were quickly rewarded. According to Moholy, "During those days there was so conspicuous a lack of simple and functional objects for daily use that even the young apprentices were able to produce models for industrial production which industry bought." The German lighting industry established links with the Bauhaus that proved invaluable to both. As Brandt recalled, "Gradually, through visits to the industry and inspections and interviews on the spot, we came to our main concern—industrial design. Moholy fostered this with stubborn energy. Two lighting firms . . . helped us enormously with practical introduction into the laws of lighting technique and the production methods, which not only helped us with designing, but also helped the firms."

All the years of struggle and change at the Bauhaus seemed to coalesce in the lighting designs which truly revolutionized the light fixtures industry. Working with new combinations of materials, especially metal and glass, Bauhaus students achieved congruity of form and function with genuinely innovative solutions that are now taken for granted. Today almost every craft studio as well as most homes and offices possess at least one lamp that is based on a Bauhaus design.

In 1927 the Bauhaus finally established a formal department of architecture under the Swiss architect Hannes Meyer. The following year Gropius resigned and appointed Meyer as the school's director. Once again the Bauhaus direction changed. Meyer felt the workshops had placed too much emphasis on "art" resulting in a preoccupation with form without giving enough consideration to techniques of production and demands of the marketplace. Concerned that the Bauhaus would become a trade school, Moholy resigned. Following his departure, Meyer reorganized the school, placing the emphasis on the architecture department. The metal, wall-painting and furniture workshops were combined under the heading of interior design and at this point metalwork ceased to be a vital area of the Bauhaus.

In 1930 Meyer resigned and was replaced by Ludwig Mies van der Rohe. Under Mies the Bauhaus developed into an academy of architecture and curtailed workshop production. In 1932, hounded by the Nazis, Mies moved the Bauhaus to Berlin. Six months later, in July 1933, the Nazis closed the school, seemingly for the last time.

Gropius's primary goal for the Bauhaus, to revitalize design, was undeniably achieved. Yet, in the process, a "Bauhaus style" emerged, a codification that Gropius dogmatically opposed. He argued that the propagation of any style, system, formula or vogue, any preconceived idea of form, "would have been a confession of failure and a return to the very stagnation which I had called into being to combat." But the school's impact on design today can be measured by the fact that the term "modern style" is synonymous with hard-edge, geometric forms in steel and glass, whether buildings or home furnishings, which are based on Bauhaus designs. Surely this cannot be characterized as a failure.

Notes:

- Walter Scheidig, Crafts of the Weimar Bauhaus 1919-1924, Studio Vista, 1967, p. 11

- Gillian Naylor, The Bauhaus Studio Vista, 1968 p. 7

- Ibid., p. 60

- Hans M. Wingler, The Bauhaus Weimar Dessau Berlin Chicago, MIT Press, 1969, p. 34

- Naylor, op. cit., p. 34

- Ibid., p. 224

- Gillian Naylor, The Bauhaus Reassessed, Herbert Press, 1985, p. 111

- Wingler, op. cit., p. 317

- Naylor, The Bauhaus Reassessed, op. cit., p. 112

- Nikolaus Pevsner, "Finsterlin," Architectural Review, November, 1962. p. 132

- Naylor, The Bauhaus, op. cit., p. 101

- Naylor, The Bauhaus Reassessed, op. cit., p. 111

- Sybil Moholy-Nagy, Moholy-Nagy: Experiment in Totality, MIT Press, 1969, p. 204

- Naylor, The Bauhaus, op. cit., p. 114

- Ibid., p. 110

- Bauhaus 1919-28, eds Herbert Sayer, Walter Gropius, Ise Gropius, Museum of Modern Art, 1938, p. 134

- Naylor the Bauhaus Reassessed, op. cit., p. 148

- Ibid.,, p. 126

- Ibid., p. 145

- Bauhaus 1919-28, op. cit., p. 136

- Naylor The Bauhaus Reassessed, op. cit., p. 147

- Ludwig Hirschfeld-Mack, The Bauhaus Longmans, Green & Co., 1963, p. 1

Further Reading:

- Bayer, Herbert, Gropius, Walter, Gropius, Ise (eds.), Bauhaus 1919-1928, New York: Museum of Modern Art, 1938

- "Fifty Years Bauhaus," London: Royal Academy of Art, 1968

- Franciscono, Marcel, Walter Gropius and the Creation of the Bauhaus in Weimar, University of Illinois Press, 1971

- Hirschfeld-Mack, Ludwig, The Bauhaus, Victoria, Australia: Longmans, Green & Co., Ltd. 1963

- Itten, Johannes, Design and Form, London: Thames & Hudson, 1964

- Moholy-Nagy, Sybil, Moholy-Nagy: Experiment in Totality, Cambridge, MA: MIT Press. 1969

- Naylor, Gillian, The Bauhaus, London: Studio Vista Ltd., 1968; The Bauhaus Reassessed, London: Herbert Press, 1985

- Pevsner, Nikolaus, "Finsterlin," Architectural Review, November, 1962

- Scheidig, Walter, Crafts of the Weimar Bauhaus 1919-1924, London: Studio Vista Ltd., 1967

- Wingler, Hans M., The Bauhaus Weimart Dessau Berlin Chicago, Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 1969

Deborah Norton is a contributing editor to Metalsmith now living in Tokyo.

You assume all responsibility and risk for the use of the safety resources available on or through this web page. The International Gem Society LLC does not assume any liability for the materials, information and opinions provided on, or available through, this web page. No advice or information provided by this website shall create any warranty. Reliance on such advice, information or the content of this web page is solely at your own risk, including without limitation any safety guidelines, resources or precautions, or any other information related to safety that may be available on or through this web page. The International Gem Society LLC disclaims any liability for injury, death or damages resulting from the use thereof.

Related Articles

Master Metalsmith Alan Adler

Ancient High Cultures: Jewelry, Talisman and Status Symbol

Etienne Perret Explores Gem Ceramic

Alternative Metalsmith Pat Flynn

The All-In-One Jewelry Making Solution At Your Fingertips

When you join the Ganoksin community, you get the tools you need to take your work to the next level.

Trusted Jewelry Making Information & Techniques

Sign up to receive the latest articles, techniques, and inspirations with our free newsletter.