1985 SNAG Platinum Jewelry Design Competition

14 Minute Read

The Johnson Matthey/Society of North American Goldsmiths Platinum Jewelry Design Competition celebrates its third anniversary this year. The competition represents a coordinated effort on the part of SNAG and Johnson Matthey to promote the use of platinum in the design of jewelry through subsidized participation. The competition is but one brief chapter in the long history of platinum, but an innovative effort to bring platinum into the mainstream of jewelry design and fabrication.

Platinum—the third member of the triumvirate of precious metals that includes silver and gold—was a significant material in the design and fabrication of jewelry and ornaments by native Ecuadorians well before the period of Spanish conquest. The extraordinary history of this rare metal, from its early use among the Indians of the New World to the end of the 19th century has been compiled in Donald McDonald's History of Platinum (London, 1960), a volume that examines both the artistic and scientific history of the metal.

From the end of the 19th century to the present day, however, platinum has been the Cinderella of jewelry, serving the role of a faithful and dependable background support for expensive, coruscating gemstones. Blessed with virtues such as durability, strength, purity of color and resistance to tarnish and corrosion, platinum has proven to be a sturdy and modest counterpoint to radiant and colorful stones. At the same time, platinum has been cursed by its apparent resemblance to silver; although its inherent value may be equal to or greater than gold, the undisputed queen of the precious metals, its physical appearance carries with it none of the rich and immediately recognizable color of its precious sister.

The low esteem given to platinum as a precious metal in its own right is confirmed by its very name, derived from the Spanish "platina," or "little silver." When platinum from South America was first brought to the attention of Europeans, it was by way of Spanish explorers who recognized the idiosyncratic nature of this silver look-alike. Platinum was a curiosity brought back to Europe for the delectation and experiments of natural historians and, as such, was classed as a poor relative of silver.

In the 18th century ambitious attempts to make use of the metal included a large number of scientific experiments intended to reveal its metallurgical secrets and the processes essential to its manipulation. Its application to the concerns of the goldsmith was of limited success; the most noteworthy examples of objets de luxe made from the material are to be found among the few extant works by the French goldsmith Marc-Etienne Janety, active in Paris in the latter decades of the 18th century.

Although current research being conducted may help to bring to light other works by this important goldsmith, by far the best known of his works is a magnificent covered two-handled sugar basin, now in the collection of the Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York. This exceptional work, following closely the models for similar tabletop refinements made by 18th-century silversmiths, treats a neoclassical theme with grace and elegance.

The body wall of the sugar basin in fully pierced, necessitating the use of an interior glass liner that provides a visual contrast to the lustrous metal. The sugar basin is architectural and monumental in conception; four tapered pilasterlike elements that define the upper body of the vessel are supported upon claw-and-ball feet. The interstices between the upright pilasters are filled with finely pierced and chased fruit and flower garlands, while the central portion is enriched by classical figures in relief of a satyr and a sleeping female. This unusual example of the goldsmiths' art applied to platinum is engraved with the signature of the maker and the date 1786.

In the 19th century, platinum was among the variety of remarkable and diverse materials used in the workshops of Fabergé in Russia, not only as a setting for precious and semiprecious stones, but as the major material for bibelots such as ladies' compacts. Also at the Metropolitan Museum of Art is to be found such a compact—a rectangular flat box with a border of faceted diamonds. The compact is suspended from a chain of set diamonds and fined with a platinum and diamond ring intended to slip comfortably over a finger when the compact was in use.

By the early decades of the present century, platinum had proven its value as an ideal setting for precious stones, and richly encrusted brooches, glittering with diamonds, rubies, amethysts and pearls were produced in distinguished ateliers such as that of Cartier in Paris. It is interesting to note that during the 19th century some of the most experimental works with unusual metals were carried out in materials today far removed in rarity and value from platinum: In the collection of Cooper-Hewitt Museum is a suite of jewelry made of aluminum, the metal we now identify with soft-drink cans.

It was not until the mid-1970s that platinum was accorded a place of honor among the precious metals in England, where a special series of marks for platinum was first used. The first vessel bearing the British platinum hallmark was commissioned from Jocelyn Burton in 1976, a covered standing cup with a stem and finial composed of undulating bands of platinum.

The nascent interest of studio goldsmiths and jewelers in the use of platinum as a metal in its own right, and not only as a background for precious stones, required encouragement. Although individual metalworkers in the United States and abroad infrequently used platinum, several problems were immediately apparent to anyone who chose to work with the material. In addition to the expense of investment in the precious metal, which severely limited free experimentation, few opportunities existed for exhibition and sales. Combined with the undeniable fact that platinum resembled silver rather than gold, the expense of production and the difficulty of marketing such expensive jewelry effectively removed platinum from the repertoire of materials in common use among goldsmiths and studio jewelery designers.

The need to stimulate the use of platinum as a viable alternative to silver and gold in studio jewelry design was recognized by the platinum industry itself. Although platinum has remained in general use for gem settings among manufacturers of jewelry, the primary applications of platinum were industrial, specifically as a catalytic agent for the production of fertilizers and in pollution-control devices for automobiles. In 1983 Johnson Matthey, Inc., a leading producer and supplier of platinum, established a working relationship with the Society of North American Goldsmiths to create an annual platinum jewelry design competition, an effort spearheaded by David Lundy of Johnson Matthey.

As announced and illustrated in the Fall, 1983 issue of Metalsmith, this innovative design competition was intended to encourage the use of platinum "in new and different ways," to expand the jewelry possibilities of the metal and, importantly, to "provide an opportunity for metalworkers to execute their creative ideas directly in platinum." Each year since 1983 the competition has been conducted along the same lines: Members of SNAG were invited to submit a single design for a piece of platinum jewelry. The sketches were reviewed by an invited jury and 10 designs selected. Johnson Matthey, Inc. supplied each qualifying designer with up to 10 dwt of platinum, with the request that the material be used to execute the design exactly as submitted. The final products were assembled and juried, and from this group the winners were chosen.

In the 1983 competition, the Grand prize was awarded to Whitney Boin for his Radar Earrings composed of thin horizontal wires of platinum held within movable circles, while the First Runner-Up awards were given to Lynda Watson-Abbot for an asymmetrical sandblasted brooch and to Phillip Fike for his animated Forged Drop earrings. For the 1983 competition I was a juror with Glenda Arentzen and Gary Griffin. Arentzen commented on the "unique qualities of platinum" revealed in the designs, while wearability and salability were less significant aspects of her choices.

Griffin, another working metalsmith, noted that the three winning designs were carefully related to the placement of the jewelry on the body. While agreeing that the winning pieces were all 'wearable." Griffin acknowledged that the 10 dwt limitation on weight may have restricted the designs. Judging from the point of view of design history rather than as a working metalsmith. I appreciated the technical expertise and visual exuberance displayed in the designs.

A primary question that arose during the first jurying session, and one that has remained important in subsequent deliberations, was whether or not the use of platinum rather than another material was a significant factor in the design and execution of the piece. In many submissions, the jurors recognized works that incorporated movement as a part of the design: along with refinements of structural delicacy that required unusual strength in the material, such considerations indicated an awareness that the inherent strength of platinum facilitated innovative designs. These practical considerations were, in the end, less significant than the basic design quality and wearability of the jewelry.

All of the jurors acknowledged that a number of the designs submitted were of less interest than might have been hoped for or anticipated. Another consideration had to be borne in mind during the jurying process: In any open competition, it is not assured that the most talented and capable of artists and designers will actually make the effort to submit. If the more innovative and successful of jewelry designers do not choose to participate in open competition, is the survey an accurate profile of the current state of jewelry design among the membership of SNAG?

For the 1984 competition, a different group of jurors were brought together that included Ettagale Blauer, Deborah Aguado and the 1983 Grand Prize winner Whitney Boin. In her juror's statement (Metalsmith, Fall, 1984, where the winning designs are illustrated), Blauer recognized the problems inherent in judging the quality of an idea from a sketch alone, reminding us that a poorly executed drawing may contain the germ of a good idea that can only he revealed in the finished work. Blauer went on to itemize the criteria used in the selection of the winning designs, including considerations of the technical feasibility of construction, whether or not the design made the best use of platinum's intrinsic qualities and, most importantly, originality of ideas.

The Grand Prize in 1984 was awarded to Norman Cherry of Scotland for his Rainbow with Arrow brooch that used platinum wire as the basis for a highly textured woven structure. Blauer pointed out that the tensile strength of the metal was important in the design and execution of the piece, while runner-up Susan Hamlet exploited the same tensile strength of the material in her Flexible Column Bracelet. Lynda Watson-Abbot, also a runner-up in the 1984 competition, took a completely different approach to the material, using the platinum in combination with gold to create a sophisticated and elegant graphic design.

In her review of the competition Blauer pointed out that many of the designs submitted to the jury were not indicative of the final product. Specifically, designs that suggested sculptural weight and substance were translated into objects that were flat and two-dimensional, or designs that promised rich textures resulted in objects that did not fulfill the promise. Blauer raised a question about the amount of weight that should be given to the initial sketch and admitted that "not every metalsmith is adept at drawing on paper." Although this problem is familiar to anyone who serves on a design jury, I feel that the presentation aspect of a designer's work merits careful consideration, since the judgment must necessarily rest upon this initial, albeit sometimes unfair, indication of an idea or concept to be realized. If the SNAG competition is intended to stimulate creative thinking in the area of platinum jewelry design, it should also stimulate creative thinking about the professionalism of the artist/designer. As objectionable as it may appear, professionalism is reflected as clearly in the presentation of an idea as in the finished work.

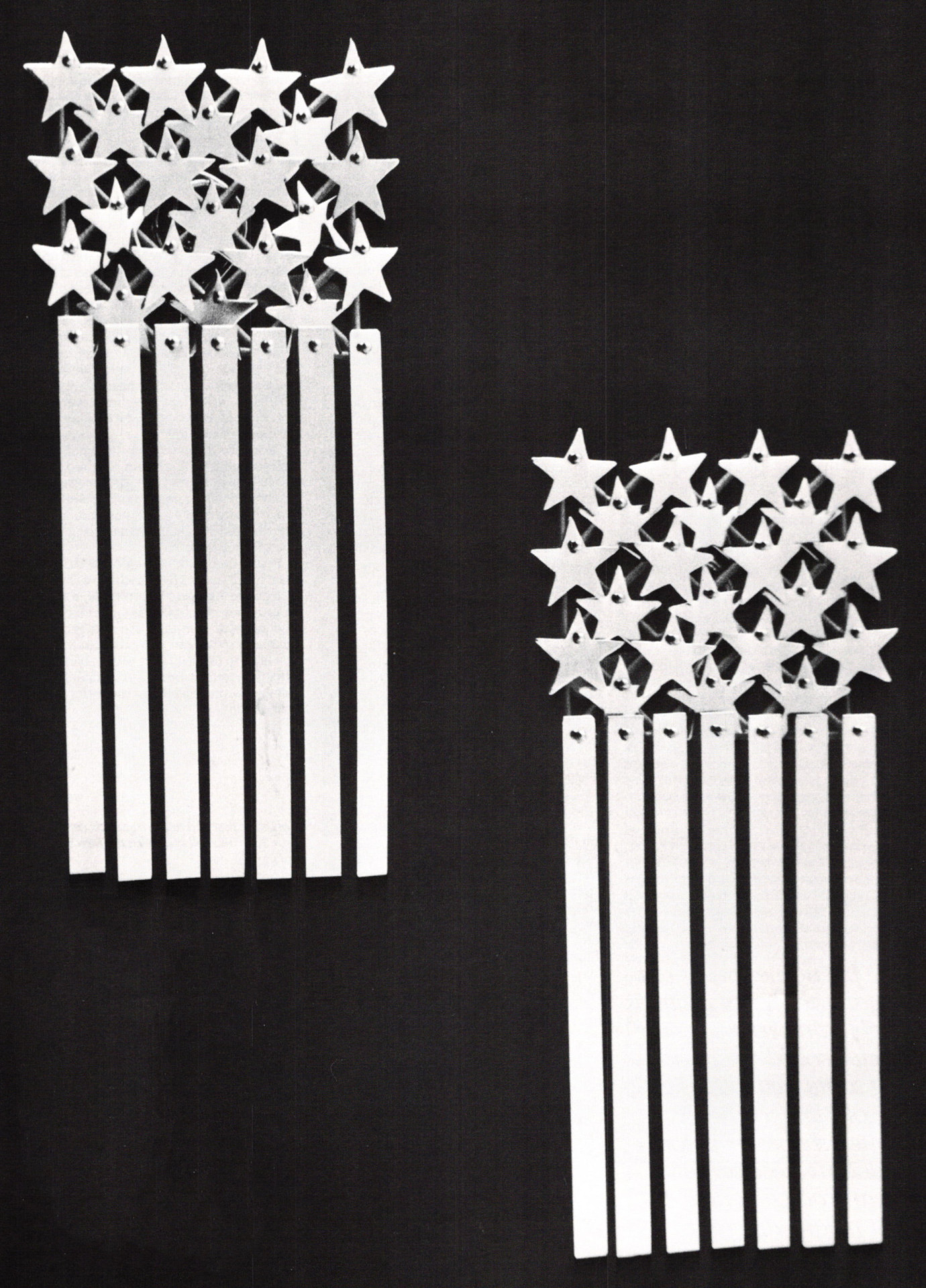

With Platinum Jewelry Design Competition completed for yet another year, now seems an appropriate time to review not only the winners of the 1985 competition, but the potential effect of the competition on the field. Again this year, I sat on the jury, this time with Sharon Church and Robert Lee Morris. For the second time, Whitney Boin was awarded the Grand Prize for his earrings, animated and lively forms based on the stars and stripes of the American flag.

Even in his initial and anonymous sketch, the jury recognized that the design contained a delightful promise that was admirably fulfilled in the finished work. The two second prize designs clearly fell within the framework of a number of earlier designs that exploited the impressive strength of the material. Both Tom Muir s and Myra T Mimlitsch's brooches made effective use of platinum wire to create evocative abstract shapes. While Muir's earrings appeared to be skeletons of architecture, Mimlitsch's brooch combined the simplicity of a found object—a segment of barbed wire—with the provocative poetry of a ritualistic symbol.

Other designs submitted following initial jurying of sketches lacked the visual and sensual presence of the three winning works. Of more than passing interest, however, was Debra Stark's woven finger ring; although the design suggested a fresh approach to the material, the ring as executed was not especially comfortable to wear, did not permit ease of movement for the finger and appeared to be too self-consciously "designed." Other ideas that made use of platinum wire were of interest, but sometimes lacked sound esthetic followthrough: entries by Tim McCreight, Kye-Yeon Son and Hikoro and Gene Pifanowski all used wire to create abstract linear forms, but all appeared stronger on paper than in reality.

An intriguing design for a finger ring was submitted by Glenda Arentzen that combined a rectilinear structure with a "caged" spiral of platinum. As with several other examples, the idea was attractive, but the final product more of an impediment that an ornament that worked gracefully with the hand of the wearer. Holly Goeckler's delicate and winglike earrings succeeded in both sketch and in execution, but their attenuated forms and precarious balance made them less successful on the ear than might have been expected. Dean A. Smith's wormlike brooch elicited great discussion among the jurors; although it was not felt that the design was particularly innovative, it was a highly wearable and appealing example of a piece of jewelry that could be readily worn by women or men. It has often been lamented that there have been so few designs submitted for men's jewelry as a part of the competition: this design, although nor an award winner, was a refreshing change from the bulk of the entries for earrings and brooches.

After three years of the Johnson Matthey, Inc./SNAG Platinum Jewelry Design Competition, it is reasonable to ask whether or not the competition has met its stated goals. Obviously, it has stimulated new work among a talented and ambitious group of young metalsmiths, and their work has been brought to the attention of the public. This alone, I believe, has made the competition worthwhile. It has always been hoped that the competition would encourage continued efforts and experimentation in the use of platinum, but this remains to be seen in the careers of the participating goldsmiths. At the same time, it is clear from the selection of initial entries each year that many talented members of SNAG do not choose to submit to an open juried competition and that the selection each year does not accurately reflect the membership of SNAG. If the members of SNAG feel it worthwhile to ask for industry support of such competitions, it behooves them to make a stronger effort to participate.

From a subjective point of view, having served as a juror for two competitions, it seems that an even greater problem may exist within the community of metalworkers itself. A majority of the designs submitted do not reflect innovative thought on the part of the artists, nor an unusual, fresh approach to platinum itself. It sometimes appears that the goldsmiths are content to repeat ideas they have found successful in gold or silver and to simply translate them into another material.

Throughout history, the art of the goldsmith has been among the most conservative and traditional due to the close and unavoidable relationship that exists between design in the precious metals and economics. However, those goldsmiths who have helped to rewrite the history of their art and craft have had the courage to pursue radical experiments within the constraints of their material and according to the opportunities that come their way. If the platinum industry is committed to the continuation of such a competition, it is necessary to complete this equation by asking for capable artists and designers within SNAG to make an even greater effort to match this commitment.

David Revere McFadden is the Curator of Decorative Arts at The Cooper-Hewitt Museum in New York City.

You assume all responsibility and risk for the use of the safety resources available on or through this web page. The International Gem Society LLC does not assume any liability for the materials, information and opinions provided on, or available through, this web page. No advice or information provided by this website shall create any warranty. Reliance on such advice, information or the content of this web page is solely at your own risk, including without limitation any safety guidelines, resources or precautions, or any other information related to safety that may be available on or through this web page. The International Gem Society LLC disclaims any liability for injury, death or damages resulting from the use thereof.

The All-In-One Jewelry Making Solution At Your Fingertips

When you join the Ganoksin community, you get the tools you need to take your work to the next level.

Trusted Jewelry Making Information & Techniques

Sign up to receive the latest articles, techniques, and inspirations with our free newsletter.