The Wearability Issue

5 Minute Read

One of the major perplexing points expressed about contemporary art jewelry is the question of wearability - or, more properly, un-wearability. Why do so many art jewelers seem to make jewelry that is too large, heavy, pointy or too fragile to be worn conveniently? The question generates considerable heat. In the Fall 1995 Society of Jewelry Historians U.S.A. Newsletter, Ettagale Blauer reiterates the question in her review of Susan Grant Lewin's book, One of a Kind, American Art Jewelry Today. "I remain mystified by the belief that something can be called jewelry yet need not be wearable. . . . Why not call it sculpture if it can't be worn?" Implicit in Blauer's question, is the proposition that unwearable jewelry is not jewelry at all. It's sculpture.

First, one has to ask: Is wearability the essence of jewelry? Non-Western cultures have produced thousands of examples of large, clunky, and heavy personal adornment that, from a Western point of view, would be considered unwearable. In Africa, Surma women of southwest Ethiopia wear large wood or clay lip plates; Fulani women in Mali wear kwottenai kanye, finned earrings six or seven inches across; Sambaru and Rendille women often wear so many beaded necklaces they cannot tilt their heads down. I could continue for hours citing similar examples from Asia, India, Oceania, and the Americas. Is it possible that not one of these many types of adornment is really jewelry? I don't think so. It would be outrageously arrogant to declare that Western standards of wearability must determine, for the entire world, what jewelry is and is not. For any student of world jewelry, sheer size and weight cannot preclude an object from being jewelry, and Blauer's implicit exclusion is wrong.

One can object that all the examples I chose are non-Western, and each culture is entitled to write its own rules. Exactly. Blauer is offering us a definition of jewelry that is essentially conservative, white, and middle class. She represents a cultural bias, which holds that jewelry should not interfere with the smooth and orderly functioning of both the physical and the social body. Jewelry should not be so heavy as to become irritating or painful; coats and gloves should pass conveniently over pins and rings. One shouldn't have to pay attention to the object they are wearing. Jewelry should make you more attractive, but it shouldn't be overtly critical or confrontational.

It does not take much analysis to realize that these rules are about as bourgeois as they can be. Beyond the pale of the middle-aged, white middle class, the rules change. On the streets of Philadelphia, African-American women routinely wear gold earrings three and four inches in diameter. Kids everywhere are getting their ears, noses, lips, tongues, nipples, and genitals pierced and their bodies tattooed. And art jewelers are making big jewelry.

For the past century, jewelry has tracked developments in the other visual arts closely. Arts and Crafts jewelry partook of the doctrines of truth-to-materials and honest labor that Pugin and Ruskin espoused; Art Nouveau jewelry presented the same whiplash line and femme fatales that appeared in Symbolist painting. Cubism; International style reductivism; Surrealism; Abstract Expressionism; each had their counterpart in jewelry. It should come as no surprise, then, that the values and methodologies of contemporary art should be applied to contemporary jewelry. And, as we well know, one of the primary values in recent art is to expand the envelope, to explore how far a given format might be stretched. Just as we had big paintings and big sculpture - really, nothing new in the broad picture - so we have big jewelry.

More importantly, however, we also have the idea of treating an art form as a vehicle for discourse. Such discourse often took the format itself as a subject: painting about painting; dance about dance. Why shouldn't there be jewelry about jewelry, jewelry that explores the nature and limits of jewelry itself? And that's exactly what happened with the so-called New Jewelry of the mid-1980s. Jewelers asked: Can jewelry be reduced to an attachment to the body and nothing else? How big can jewelry become before it ceases to be jewelry? The result was the work of Pierre Degen, Johanna Hess-Dahm, Caroline Broadhead, and many others. While such work appeared wildly radical, from an informed point of view it also appeared historically necessary.

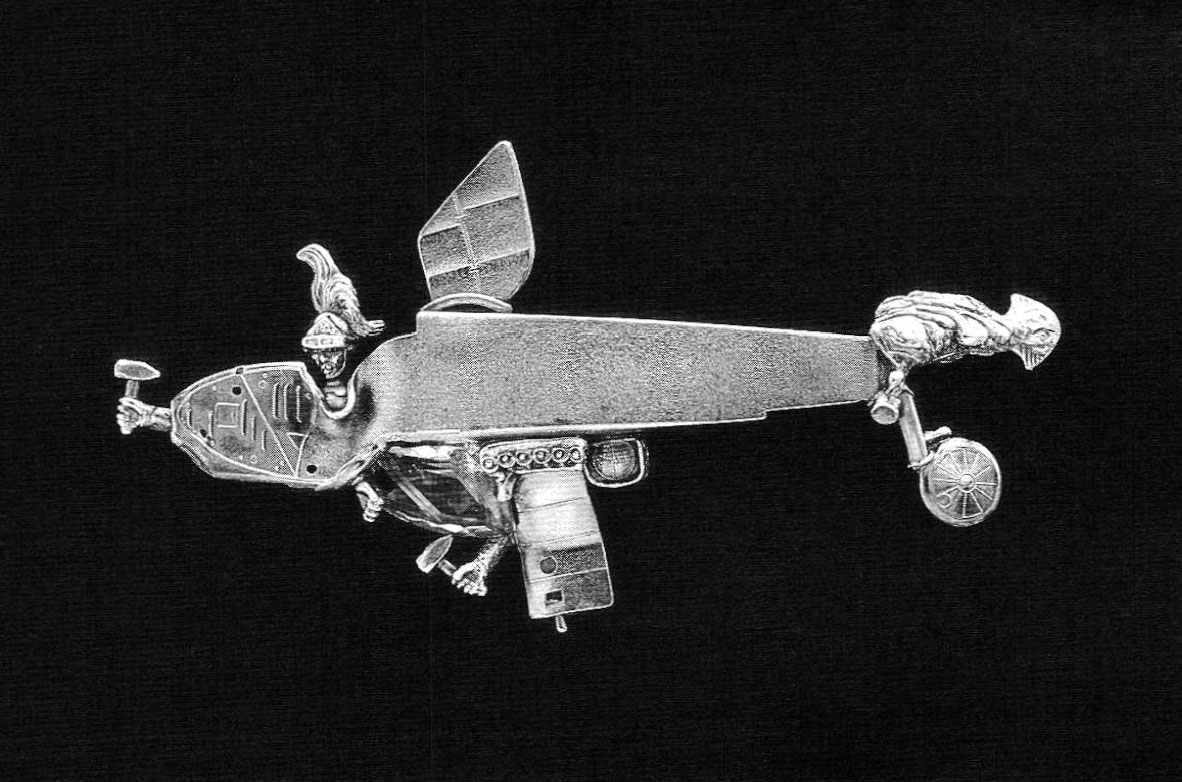

It didn't take long before the subject of the jewelry discourse expanded beyond jewelry itself. Fred Woell was one of the first to employ jewelry as a vehicle for social commentary, as in The American Way pendant, which quietly condemned the American penchant for violence. Once jewelry became a vehicle, the jeweler had to make choices about priorities. What is more important, strict wearability itself a flexible criterion; or getting the point across in the clearest possible way? Each individual may make a different choice, but some will sacrifice wearability.

There is a traditional, middle class view of jewelry, and an art-world infected view. I have to stress that neither view is universally correct. Each has a context, within which it makes perfect sense. My Mom, who wants her jewelry to be a visual accent and an emblem of her social status, would agree 100% with Ettagale Blauer. Forcing her to appreciate a Caroline Broadhead monofilament veil would be a waste of time. And yet, an artist who has been steeped in the discourse of twentieth-century art would not find my Mom's diamond rings very interesting. Such an artist wants to see jewelry that engages in that long and complicated conversation.

The friction comes when the two views struggle for dominance. I think the key - and I have to admit that I find it difficult - is to exercise tolerance. I may not be terribly interested in another point of view, but I don't have to make it submit to my value system, either.

Bruce Metcalf makes jewelry and teaches occasionally in Philadelphia.

You assume all responsibility and risk for the use of the safety resources available on or through this web page. The International Gem Society LLC does not assume any liability for the materials, information and opinions provided on, or available through, this web page. No advice or information provided by this website shall create any warranty. Reliance on such advice, information or the content of this web page is solely at your own risk, including without limitation any safety guidelines, resources or precautions, or any other information related to safety that may be available on or through this web page. The International Gem Society LLC disclaims any liability for injury, death or damages resulting from the use thereof.

The All-In-One Jewelry Making Solution At Your Fingertips

When you join the Ganoksin community, you get the tools you need to take your work to the next level.

Trusted Jewelry Making Information & Techniques

Sign up to receive the latest articles, techniques, and inspirations with our free newsletter.