Urushi: Japanese Lacquer

5 Minute Read

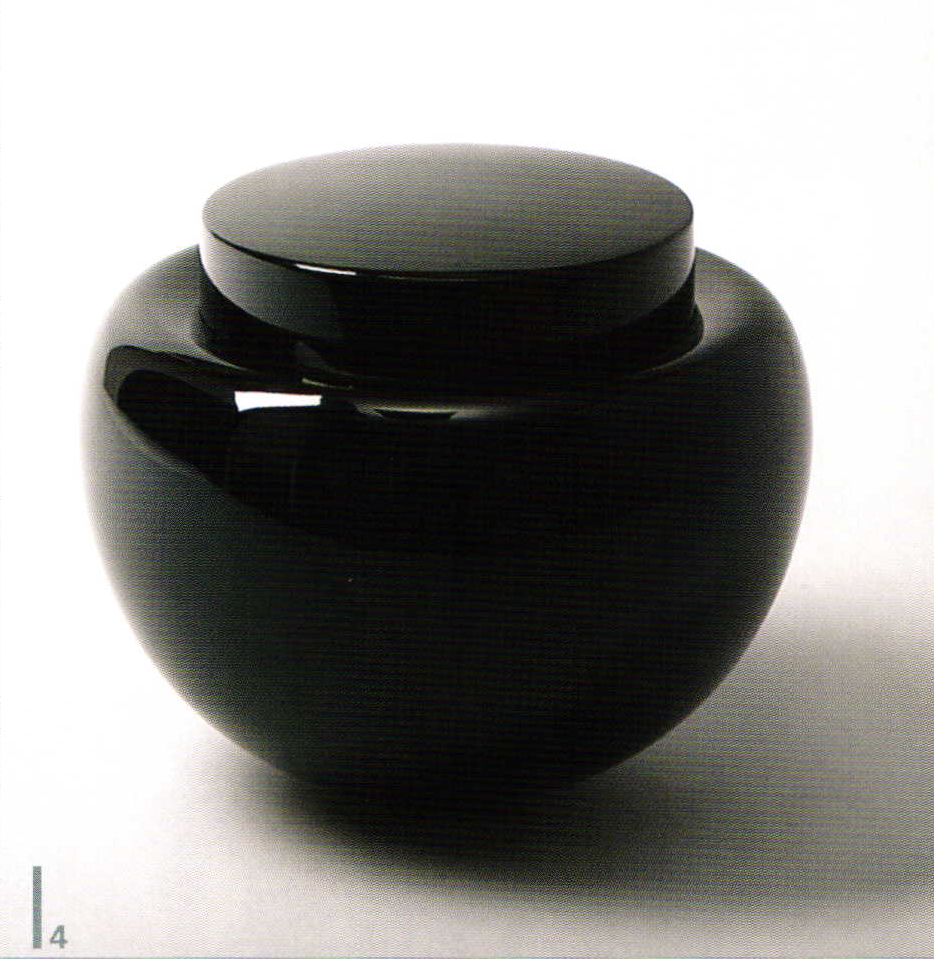

Urushi is the sap from a staghorn sumac tree (rhus vernicifera) which is native to East Asia. Japanese and Chinese lacquer of the century old lacquering technique is based on this sap. The Japanese name is urushi. The exclusive surface is used for vessels, writing instruments, ceremony objects, art objects and lately more and more for jewelry. Because the lacquering technique is not yet a lot used for contemporary jewelry there is a wide field for unique new designs. The deep effects of an object lacquered with urushi lacquer are just as fascinating to the observer as the silky surface. Traditional urushi work takes 20 to 50 layers of lacquer.

Mariko Nishide, "A Siesta", 2D urushi lacquer painting, colored urushi and silver grains

The sap urushi, once harvested, is filtered, mixed, concentrated and finally colored. Urushi is traditionally used for making wooden barrels more durable and providing decoration. Before the days of refrigerators, meals were stored in Japan in sealable stackable urushi containers as bacteria don't live for more than 24 hours on urushi. The origins of urushi lacquer date back to the Stone Age. Archaeologists discovered that arrowheads were secured to wooden spears using urushi lacquer which proves that two of the most impressive characteristics of urushi resin were known at that time: the strength of the dried resin and its incredible adhesion to other materials. With the introduction of Buddhism in the 6th century urushi lacquering technology was brought to Japan by Chinese and Korean monks. During the Edo era, from 1600 to 1868, urushi technology was perfected. Urushi work became part of the tea ceremony in the form of tea containers and ceremonial pieces for incense sticks. Lacquered hair combs belonged and still belong to the kimono costume. Urushi was also used as an important decorative technique for swords and amour.

After the Dutch import firm Dutch East India Company began to import lacquered furniture from Japan and China to Europe in the 17th century, attempts were made to imitate this unique surface. The urushi technique could not be carried out in Europe as the right tree would not grow there. It was also impossible to avoid the hardening of the urushi lacquer during the long transportation process. The imitation lacquer developed was called Japaning and was composed of shellac, sandarac (resin from a shrub-like or tree-like conifer) or amber. The color palette of this lacquer was considerably greater than with urushi lacquer although the use of materials of different origins led to uneven aging and thus to stress cracks. For the first time Japan took part in an international exhibition in 1867. This exhibition was held in Paris and the urushi pieces were the publics favorite and later went on to influence Art Nouveau.

Silvia Rodo Ferrer (student at Escola Massana, Barcelona), necklace "Puzzle", alpaca oxide and brass with urushi rice technique, gold leaf

Silvia Rodo Ferrer (student at Escola Massana, Barcelona), necklace "Puzzle", alpaca oxide and brass with urushi rice technique, gold leaf

Kenji Omachi, amber piece, urushi makie-technique

Mariko Nishide, "A Spring Dawn", colored urushi, gold and silver grains

Urushi objects and furniture were seen as a status symbol. In 1898, Japanese lacquer artist Seizo Sugawara emigrated to Paris to help with the construction of the Japanese pavilion for the International Exhibition in 1900. Irish architect Eileen Gray, Swiss designer Jean Dunand and others learned the traditional technique from him, thus replacing the Japaning technique. In the meantime, transport had also become faster and packaging materials better so that urushi lacquer could now be imported.

Today there are a few craftsmen in Europe who have learnt this complicated lacquering technique either from Japanese masters of lacquering or in Spain. One of these few masters of lacquering in Europe is Mariko Nishide. She lives and works in a suburb of Amsterdam and is a member of the International Council of Museums (ICOM) and the International Committee of Conservation (ICOM-CC). She is an urushi artist, urushi restorer and poet. The restorer and master lacquerer Gunther Heckmann from Ellwangen lived in Toronto with his urushi master Tomizo Saratani for three years following the Japanese example and stayed with his master's family, learning the urushi technique. In 2002, Gunther Heckmann published his book 'Urushi' (see page 86).

Thelma Aviani, necklace, polymer Prolab-80, covered with 19 layers of urushi

Salome Lippuner, brooch "Shunkei Nuri", nature colored urushi lacquer painting on maple wood, white gold, silver

Swiss-born Salome Lippuner works intensively with urushi. She learnt the technique over many years. Lippuner is captivated by the "bright and yet soft shine which brings surfaces and volume to life, by the subtle transparency which lights up the deep-lying structures and inlaid materials and by the silky-smooth warm surface which provides a feeling of luxury when touched". Because of her technique of to use many thin layers (up to 60) Salome Lippuner was invited to Wajima, Japan to work with urushi lacquering masters for two months. Sakurako Matsushima graduated from the Tokyo University of Fine Arts and Music and today works as an assistant at the Utsunomiya University, Japan. Manfred Schmid from Bremen learnt the urushi technique in Barcelona. For him the European lacquering tradition still has its roots in Spain. The Escoa Massana in Barcelona has many international students who take it upon themselves to learn Spanish so that they can learn the urushi technique here. Gesine Hackenberg took intensive courses with Mariko Nishide for three years and is fascinated by urushi characteristics now more than ever: "With my items of jewelry, gold and silver scratch but not the urushi."

Salome Lippuner, urushi-bracelet "Negoro Kodaishu"

Sakurako Matsushima, "Undercurrents 2", 2006, size: 70x53x4,5 cm, urushi, bamboo, hemp cloth, gold powder

Manfred Schmid, pear, urushi, silver foil, 14.5×9.5cm

Manfred Schmid, kanshitsu-technique, red urushi, gold leaf

Gesine Hackenberg, "Black medaillon with spring", 2006, urushi, silver

Gesine Hackenberg, "Stacking Medaillons", object/brooches,clips, urushi, silver

Sakurako Matsushima, "Undercurrents 1", 2006, size: 63x73x9 cm, urushi, bamboo, hemp cloth, abalone shell, turban shell, gold powder

by Christine Patrich

You assume all responsibility and risk for the use of the safety resources available on or through this web page. The International Gem Society LLC does not assume any liability for the materials, information and opinions provided on, or available through, this web page. No advice or information provided by this website shall create any warranty. Reliance on such advice, information or the content of this web page is solely at your own risk, including without limitation any safety guidelines, resources or precautions, or any other information related to safety that may be available on or through this web page. The International Gem Society LLC disclaims any liability for injury, death or damages resulting from the use thereof.

The All-In-One Jewelry Making Solution At Your Fingertips

When you join the Ganoksin community, you get the tools you need to take your work to the next level.

Trusted Jewelry Making Information & Techniques

Sign up to receive the latest articles, techniques, and inspirations with our free newsletter.