Smalt (Ground Glass)

12 Minute Read

Smalt is a word used to describe ground glass when it is either mixed with oil and applied to canvas, or strewn on top of a tacky paint surface. Glass artisans and enamelers have known about this material for centuries, and others no doubt learned about it from those two trades.

By the fifteenth century, it appears in the work of artists in Northern Europe as a cheap substitute for the very expensive ground lapis lazuli. Afghanistan was the source of lapis, and the color was called, in English, 'ultramarine' from the Italian oltramarino, meaning 'from beyond the seal'. Finely ground blue glass, colored with cobalt, was used by artists such as Pieter Breughel, Peter Paul Rubens, Rembrandt and Vermeer. Once Prussian blue was discovered in the 18th century, that variety of smalt was no longer required, and today it is used only by art conservators restoring the paintings of pre-nineteenth century artists.

A coarser grind of glass, also called smalt, still survives as a glittering, light-reflective addition to outdoor advertising signs. A hanging board with carved and gilded letters-'Pete's Tavern', for example-and a black background, might have black smalt as the top layer, attracting more attention than just a flat painted surface.

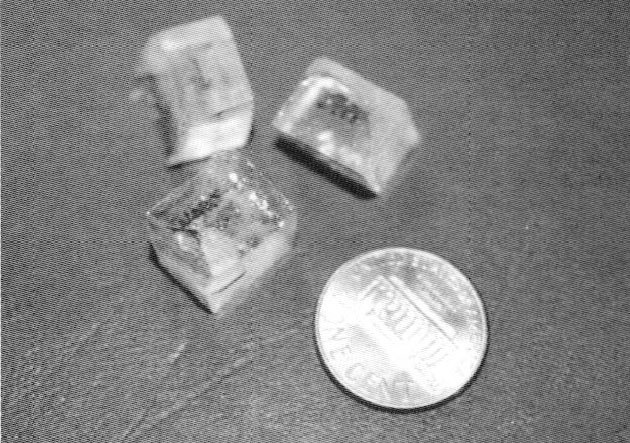

In between these two sizes of smalt is a third, referred to in old texts as 'strewing smalt' (Fig. 1). This is the kind that brought smalt into my life.

I have been the curator of the Warner House in Portsmouth, NH (Fig. 2) since 1994. During the intervening years, we have been working hard to use documentary evidence and family history to restore and interpret the house realistically, rather than the romantic, idealistic Colonial Revival approach that existed when I came.

The house was built in 1716-18 by Archibald Macpheadris, a Scots-Irish immigrant and very successful merchant, trader and ship owner. He married Sarah Wentworth, one of the daughters of the Royal Governor of the province of New Hampshire, and this was their home. He died in 1729, and in 1734 she married again, and eventually her brother, Benning Wentworth, now Royal Governor, moved in around 1742. He tried in vain to have the provincial assembly pay for repairs, redecoration, and eventually to buy the house as the official governor's mansion, but was always rebuffed. He left in disgust by 1759 and moved to his farm on the outskirts of town. His niece, Mary Macpheadris, daughter of Archibald, took over her father's house in 1760 with her new husband, Jonathan Warner, also a wealthy trader and ship owner. They did some lavish redecoration.

The parlor bedchamber was the most important of the upstairs rooms in the eighteenth century. It was directly above the parlor, and usually had the same large proportions. In the case of the Warner house, it also had the same ornately molding wood paneling (Fig.3).

Warner died in 1814, and there is, fortunately, an inventory of the house done at that time. In the parlor bedchamber, he had "10 mahog'y Chairs u'r Green damask bottoms … 1 Easy Chair Do Do … 1 maple night Chair Do … 1 Mahog'y high post Bedstead Canopy & Curtains green damask." We plan to restore this room to Warner's occupancy 1760-1814 with all the green damask upholstery. Two Chippendale chairs of a set that was once in the house have been gifted recently, and we have been promised another five by family members, so we will have at least seven of the ten. A wonderful Portsmouth easy chair is another promised gift, and we were recently given a completely fitted night chair in 2003. We will be copying a fragmentary set of gold damask bed hangings resting in the Winterthur Museum textile storage boxes which come from northeastern Massachusetts and are right for the date. Clarissa de Muzio, a textile expert who specializes in bed hangings, is supervising this project for us.

We needed to test the paint layers to determine what the Warners had on their paneled walls. New England frugality and genteel poverty are both great savers of historic structures, and the house had remained in connected family hands right up to 1930. That's when it was bought by a group of determined summer residents and their friends who saved it from being torn down and a gas station being put in its place. By 1932, it opened as a house museum, and has been open ever since.

The family had gradually drifted away from Portsmouth, the ambitious ones to larger cities and new territories in the West. Portsmouth was in decline, and by 1900, the area of town where the Warner House was had become the town's most disreputable scene. The last two members of the family who came there, and only in the summers from about 1880 on, died in 1929 and 1930. Because they were frugal, and money was tight by then, the house was never electrified, no plumbing was put in, and no heating, as the house was closed in the winters.

They also did little redecorating. The walls of Warner's bedchamber have only eight layers of paint, and two of those were put on after 1930. That leaves six. We know Macpheadris slathered iron oxide red almost everywhere in the house, treating it with different faux finishes in various rooms - marbleizing, tortoise-shell patterning, etc. It's there over the original wood in the bedchamber, but we've not been able to determine the treatment given to in that room. Benning Wentworth, we know, was not successful in obtaining any money to spend on the house, and as he didn't own it, was unlikely to spend his own, so probably lived with whatever finish Macpheadris had there. When Warner died in 1814, his widowed niece who had inherited the house, her daughter and husband did another major redecorating.

The second paint layer, therefore, was likely Warner's. A summer intern did some rudimentary testing of the layers, and took some sample cross sections which were embedded in plastic and examined in a laboratory (Fig. 4). That layer was a very pleasant rosy mauve.

Richard Candee, our Board Chairman then and the founder of the graduate program in historic preservation at Boston University, had provided the intern. She was one of his students, but Richard felt something might have been missed. He sent her samples to a friend in the National Parks Service who does paint analysis, and she concurred, but couldn't quite tell what it was.

This prompted us to call Brian Powell at Building Conservation Associates in Dedham, MA, a top expert in the field of paint analysis, and set up a date. Brian came out one cold winter day in early 2002, and took his own much larger samples (Fig. 5). And there it was - blue smalt embedded in the mauve paint. Subsequent testing established that this fascinating finish was every where in the room, from the top of the cornice to the rail just over the baseboards.

Richard has done much research on Colonial painting. Indeed, he co-authored with Abbott Lowell Cummings the chapter in the 1994 publication Paint in America Entitled 'Housepaints in Colonial America.' Smalt is not mentioned there, but he provided me with the titles of all the references to it he had found, so I began my own research several steps ahead. In this day of computerized library catalogs, it is a joy to be able to go to your local librarian (in my case, the clever Kate Giordano of the Portsmouth Public Library), find out where the books are located that you need, contact the librarian there and arrange for a photocopy of the pages you want. I soon had a nice stack of reference material at hand, ranging in date from 1723 to the present.

After reading them all, I was discouraged to find that the earliest description on how to apply the smalt was simply repeated by subsequent writers. No one added any new information. John Smith, in that 1723 volume, discusses the painting of clock faces and advises, "[T]hen take Smalt, and the Work to be done over with it lying flat, strowing it thick on the thing to be coloured, and with the feather edge of a Goose-Quill stroke over it, that it may lie even and alike thick on all Places; and then with a Bunch of Linnen Cloath, that is soft and plyable, dab it down close, that it may take well upon the ground to be thoroughly dry, then wipe off the loose Colour with a Feather, and blow the remainder of it off with a pair of Bellows, so is your Work finished."

Obviously, he was talking about that in-between size known as 'strewing smalt'. But how to find this? I had visions of Skyy Vodka bottles and steam rollers. Then I had an appointment with Dr. Peter Dinnerman, my dentist, where grinding, of course, comes naturally to mind. I remembered that Peter's father made very handsome art glass bowls and plates with a cobalt blue lacy pattern and clear glass, and called Maurice Dinnerman when I came home. I asked what he used for the cobalt, and he said "Ground Glass". I said I'd be right over, and that's how I learned about Thompson Enamel, just the source I needed. The strewing smalt was found. And I'd like to add that the owner, Woodrow Carpenter, has been most cooperative in every way, for which we are all most grateful.

No one addressed the problem of applying smalt to a vertical surface. We couldn't remove the panels to lay them flat, as Smith instructed. We had to find a workable method on our own.

I made some calls and wrote some e-mails. It's been found in England, mostly in seventeenth century contexts, but only as an accent. In the Queen's House in Greenwich, it was used to color part of the decorative design of the iron stair railing. At Hampton Court, it colored iron lamps on the Queen's Staircase. At Kew Palace, it appears in a plaster frieze design in the Queen's Drawing Room. All the ironwork could be laid flat, and, depending on the technique used, perhaps the plaster frieze as well.

I called Dennis Page, Director of Restoration at George Washington's Mount Vernon, to ask how they applied the sand to the exterior of the building. The wooden walls have been made to look like masonry blocks, and the grainy appearance of the sand or ground stone on the surface adds to the illusion. He told me they used an air compressor and a blowing device. He sent me a photocopy of Washington's instructions to his house manager, asking that he make two test boards to determine whether fine sand or ground stone gives the best appearance. "Paint them in the usual manner with white lead grd. in oil and after the first coat is dry give them a second (the paint a little thicker) and while it is fresh throw (the board standing perpendicular on one edge) sand against one, and pounded stone against the other, as long as they will stick, and till every part of the paint is well covered."

The air compressor delivery was certainly not used in our 1760 decoration, but gave us some ideas. We decided to hold 'The Great Smalt-Out', which we did on July 19, 2003. I found four painter-artists, each very creative, and explained the problem, asking if they would come up with inventive ideas on how the smalt could be applied. One of them made four boards, each 2′ x 3′ with one large piece of molding nailed on and painted the dark red undercoat. On the day of the Smalt-Out, we covered a large table with plastic sheeting to catch the excess smalt so we would know how much we used for the 24 sq. ft. of boards by weighing what we had left and deducted the amount from the five-pounds we had. That way, we could estimate how much the entire room would require (Fig. 6).

Our four painters - John Angelopoulos, Mark Drew, Lara Mitchell, and Bud Swensen - performed superbly (Fig. 7). Bud tried a flocking gun that Woodrow Carpenter kindly loaned us with an air compressor, and a wet/dry vacuum. Lara explored several different methods of hand-strewing, or pressing the smalt into the paint. John used a hair dryer with a delivery system he rigged, and various strewing techniques with a wide brush. Mark provided what proved to be the best tools - a weed-sprayer and a craft shop glitter gun (Fig. 8). Both these were hand-pumped, the kind of technology that was readily available to Warner's painters, and gave a nicely even coating. When he used one and then the other on top, the density increased and the result was a good thick coat, what Brian Powell felt was correct (Fig. 9). So this double application is what we will use when we do the actual painting, with luck, next spring. We are awaiting word from a foundation that may fund this project.

It doesn't show well in photographs, but the finish is surprisingly beautiful, a soft and subtle purplish shade which gives off gentle sparkles as you move by these boards. An entire room with it will be spectacular indeed.

This is ground-breaking stuff. No one has ever found smalt used to decorate an entire room, and therefore, no one has reproduced such a room. Brian knows that the English doubt we have it everywhere and has been meticulous in his investigation as he's the fellow who will be questioned. I have discovered that smalt has been found in two Newburyport, MA, houses, the Spencer-Pierce-Little House owned by the Society for the Preservation of New England Antiquities, and a private house in the same town, though neither has plans to restore it. Its use in both seems to be limited, but the testing was not as extensive as ours. Our smalt was missed on the first try, remember, so there may be much more out there that hasn't been revealed so far. I hope our restoration of this light reflective surface treatment will make the historic preservationists more aware of the existence of this finish, and that as a result, more such rooms will be found.

References

Victoria Finlay, Color: A Natural History of the Palette (New York: 2003), 281.

A list of the different artists is provided in Roy Ashok, Ed., Artist's Pigments: A Handbook of Their History and Characteristics (New York: 1993), 727-729.

John Smith, The Art of Painting in Oyl (London: 1723), 70.

Quoted in a letter to the author by Dennis Pogue, 4/29/03, from Writings of Washington, November 1796.

You assume all responsibility and risk for the use of the safety resources available on or through this web page. The International Gem Society LLC does not assume any liability for the materials, information and opinions provided on, or available through, this web page. No advice or information provided by this website shall create any warranty. Reliance on such advice, information or the content of this web page is solely at your own risk, including without limitation any safety guidelines, resources or precautions, or any other information related to safety that may be available on or through this web page. The International Gem Society LLC disclaims any liability for injury, death or damages resulting from the use thereof.

The All-In-One Jewelry Making Solution At Your Fingertips

When you join the Ganoksin community, you get the tools you need to take your work to the next level.

Trusted Jewelry Making Information & Techniques

Sign up to receive the latest articles, techniques, and inspirations with our free newsletter.