Book Review – Art Jewelry Today

The very term art jewelry has been bandied about so much within the past few decades that one must endeavor to apply the designation correctly, and, when attempting a book of this scope, fairly comprehensively. It would be impossible to include every artist jeweler working at this moment in time; therefore, the author should have chosen more carefully or qualified her objectives. It would have been preferable to narrow the boundaries and cover only one aspect of the movement, for example...

7 Minute Read

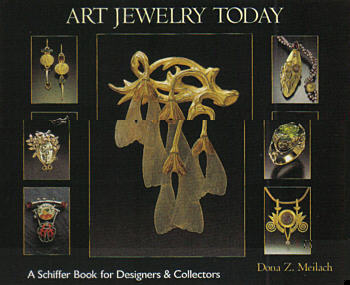

Art Jewelry Today by Dona Meilach is an ambitious, sumptuously illustrated book. It is logically organized, with the most successful chapters covering materials and techniques. The book functions best, therefore, as a handmade jewelry primer. Nonetheless, the author attempts to do much more, and as an overview of the current state of this thirty-year movement, which the title, foreword, and lavish presentation imply, it fails.

| Art Jewelry Today By Dona Z. MeilachManufacturer: Schiffer Publishing Release data: May, 2003 |

The very term "art jewelry" has been bandied about so much within the past few decades that one must endeavor to apply the designation correctly, and, when attempting a book of this scope, fairly comprehensively. It would be impossible to include every artist jeweler working at this moment in time; therefore, the author should have chosen more carefully or qualified her objectives. It would have been preferable to narrow the boundaries and cover only one aspect of the movement, for example, American jewelers, noble materials, jewelry inspired by nature, or large-scale works. Although Meilach states that jewelers from 14 countries are represented, the omissions are disturbing. She ignores many of the major Europeans, such as David Watkins, Wendy Ramshaw, Gijs Bakker, Manfred Bischoff, Esther Knobel, Peter Skubic, Ramon Puig Cuyas, and Giampaolo Babetto, in favor of examples that are often puzzling.

Apparently, the jewelers were selected from entrants and suggestions provided by certain professionals in the craft-as-art field. Meilach, however, offers a biased view. Too many of the pieces presented are over-decorated; and she all but ignores works that are pure or minimal. Donald Friedlich's subtle, structured pins and Svatopluk Kasaly's elegantly graceful neckpieces are exceptions. Galleries that show a broad range of contemporary jewelry, including the restrained approach, such as Jeweler's Werk, Charon Kransen, Sienna, Ra, Marzee, V&V, Spektrum, and Biro, don't appear to have been consulted.

Clearly, the author features some great jewelers, several of whom are stalwarts of the movement, such as Arline Fisch, Marjorie Schick, Nancy Worden, David C. Freda, Barbara Stutman, Harriete Estel Berman, John Iversen, Keith Lewis, and Charles Lewton-Brain. But, overall, the quality of her analysis is so uneven and the selections so random that her overview is misleading. Meilach divides her chapters into suitable stylistic approaches. But how can one show alternative materials, for example, without mentioning Thomas Gentille, Ruudt Peters, Fritz Maierhofer, Joe Wood, or Pavel Opocensky; geometry without Anton Cepka, Eva Eisler, or Michael Becker; enamels without Jamie Bennett, Maria Phillips, or Kathleen Browne; narrative without Bruce Metcalf, Daniel Jocz, or Christina Smith; found objects without Robert Ebendorf, Kiff Slemmons, or Laurie Hall; and new approaches without Bettina Speckner or Karl Fritsch? "Empirical" metalsmithing is a category Meilach totally disregards, and in so doing ignores three of art jewelry's strongest practitioners: Tone Vigeland, Myra MimlitschGray, and Bettina Dittlmann.

The book gives little sense of the movement's roots or nascence. There is only a cursory allusion to the vital cross-fertilization between Europe, Asia and America, not to mention specific influences by instructors at the important college metalsmithing programs, or the early pioneers. Meilach sums up this entire phenomenon by writing, "Arline Fisch….explored jewelry as body sculpture. Other teachers picked up on the trend; Albert Paley and Marjory [sic] Schick influenced this emergence that jumped the ocean and was caught by craftspeople in Post-war European countries." There is a necklace by Juan Carlo Caballero-Perez that looks as though it could have been made by Albert Paley in the early 1970s. Who is Caballero-Perez, and what is his connection to Paley, if any? Meilach offers little biographical information. It would have helped immeasurably to know where the jewelers live, how old they are, where, and with whom, they may have studied, if, and where, they have exhibited, and if they have received any awards or accolades. She also fails to date the pieces shown, providing no basis to determine when a work was made within an individual artist's career.

Although Meilach occasionally offers some spotty background orientation, such as in the chapter on glass, her historical facts are not only incomplete but too often devolve into silly commentary, such as "Designs based on the linear forms of Hector Guimard of France and Rennie Macintosh [sic] of Scotland, have been reinvented in jewelry and are being sold in museum stores today." Furthermore, her research is sloppy and inadequate. In the chapter on found and recycled objects, she writes: "Using found objects for body adornment may have gotten its start during the Hippie days of the 1970s…. Whoever and wherever it began is not as important as where it has led…." Apparently, the author is unaware of the Victorian use of hummingbird heads for hatpins or Dadaist Meret Oppenheim's earrings made from thermometers. Granted, it would be unreasonable to expect the author to be well versed in such specific (and, perhaps, esoteric) historical data, but her cavalier attitude is a cop-out.

Meilach illustrates almost every chapter with photographs of ethnic peoples, inexplicably, mostly New Guinean tribesmen, however, she fails to give any but the most puerile reasons why they were chosen or how they relate to the contemporary jewelers discussed. Dancers from Papua, New Guinea, for example, shown wearing headdresses and neckpieces made from feathers, beads and shells, open the chapter on found and recycled objects. Meilach advises the reader: "Study the photo carefully to observe how different types of shells, feathers, leaves, nuts and vines become jewelry." She goes on to point out how "primitive adornments" inspire traditional jewelry and how department store jewelry counters display feather shaped pins, shell shaped beads, and braided bracelets of silver and gold, while fashion advertisements encourage one to wear layers of beaded necklaces. Artist jewelry is belittled placed within this context. By the same token, the chapter on glass opens with Masai girls wearing traditional collars of tiny glass trade beads, but nowhere in the text does the author show how either the form of the individual pieces or their overall effect has inspired any contemporary maker in the way, for example, the posthumous discovery of archival magazine photos of Watusi dancers in full regalia, found amongst modernist jeweler Art Smith's possessions, proved enlightening. Visual associations to generalized tribal motifs are somewhat apparent, but specific comparisons, within the text, such as with Cynthia Toops's polymer clay necklaces or Kandioura Coulibaly's clay bead necklace, are rare. For the most part, relationships are left to the reader's imagination.

Meilach minimizes the serious commitment and artistic intent of the jewelers. She writes: 'The artists who create one-of-a-kind pieces might be your neighbor working out of a garage or a small room. They are your friends, your children's friends, for jewelry making is a hobby for many, a business for others." This passage reads like something out of a 1950s how-to manual. At a juncture where artist jewelers are still struggling for credibility, this comment is sadly misleading. There is, furthermore, no mention of the countless museum exhibitions, both in the United States and abroad, which have included jewelry by artists and recognize the movement as one worthy of serious consideration.

The jacket flap states that Dona Meilach has written more than 85 books on topics including macrame, batik and tie-die, fireplace accessories and creating modern furniture. Her Ethnic Jewelry: Design and Inspiration for Collectors and Craftsmen (1978) is in my library. It is of its time, and she has a real affinity for this subject. The book is an asset to any jewelry enthusiast. The problem with Art Jewelry Today is that Meilach attempts too much with too little insight. An up-to-date account of this decades-old movement is sorely needed. But Art Jewelry Today lacks curatorial focus, qualitative judgment, broader context, and a sense of cause and effect. The author seems to intend a sweeping survey, but because the content is so uneven and its endorsements so indiscriminate the book does little to develop connoisseurship. The reader is given no guidelines to judge the best from the banal, the art from the craft, and the well-conceived from the excessive.

Over the years, there have been several excellent books written about "art jewelry." Meilach references a few in her bibliography. This is part of the problem with her book. There is no need to dumb down the topic, since a roster of benchmark literature already exists. The flap states: "In the twenty-first century, craftspeople are striving to have their work considered fine art. This book will convince doubters that today's art jeweler is creating serious sculpture…." An argument for art status, however, must be made within the established vocabulary of the discipline. There still exists a raging polemic about what constitutes "art jewelry." Those committed to the field are working exhaustively towards establishing an art jewelry canon. In presenting an inadequate and distorted view of the movement, Art Jewelry Today undermines their efforts.

You assume all responsibility and risk for the use of the safety resources available on or through this web page. The International Gem Society LLC does not assume any liability for the materials, information and opinions provided on, or available through, this web page. No advice or information provided by this website shall create any warranty. Reliance on such advice, information or the content of this web page is solely at your own risk, including without limitation any safety guidelines, resources or precautions, or any other information related to safety that may be available on or through this web page. The International Gem Society LLC disclaims any liability for injury, death or damages resulting from the use thereof.

The All-In-One Jewelry Making Solution At Your Fingertips

When you join the Ganoksin community, you get the tools you need to take your work to the next level.

Trusted Jewelry Making Information & Techniques

Sign up to receive the latest articles, techniques, and inspirations with our free newsletter.