Metalsmith ’94 Spring: Exhibition Reviews

33 Minute Read

This article showcases various exhibitions in the form of collected exhibition reviews published in the 1994 Spring issue of the Metalsmith Magazine. This features Komelia Hongja Okim, Curtis LaFollette, Julia Barello, and more!

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

17th Annual Philadelphia Craft Show

November 4 - 7, 1993

Philadelphia, Pennsylvania

by Dorothy Spencer

With the "Year of American Craft" quickly drawing to a close, over twenty-six thousand patrons attended the four-day Philadelphia Craft Show illustrating an ever-growing trend of enthusiastic support - both financially and esthetically - for the craft market.

This annual event attracted over 1,600 applicants from around the country. From that exceptionally large number, only 175 artisans were selected to show their work. And of those exhibiting, nearly one-third were categorized as either jewelers or metalsmiths and half of the prizes awarded went to artisans working in these areas.

First prize was awarded to Robin Kranitsky and Kim Overstreet for their unique, collaborative, wearable, dioramas. Although the pieces are made from a variety of found objects and constructed in nonprecious materials, they are remarkably beautiful, offering thought-provoking miniature tableaus. These tiny scenes seem to be fantastical, magical moments captured and frozen in time, then reduced in scale.

Rick Smith took third place in the show and brought new dimensions to the art of blacksmithing. Using forging, welding, and fabrication the artist creates vessels which are architectural statements. The works' elegant designs are simple, coupling Art Deco inspired borders with strong, almost monolithic-like lines belying a complexity of technique.

Michael and Maureen Banner's serenely elegant, one-of-a kind, silver teapots with their curvilinear lines reminiscent of German Art Nouveau, won the Rolex Prize for Excellence in Metal. Pristine in design and fabrication many of the handsomely finished pieces included cloisonné lids and long, swooping handles.

Jaclyn Davidson won the Touches Prize for excellence in jewelry. Ms. Davidson, whose work is an extraordinary example of basse-taille (shallow cut) enameling, makes lost-wax cast and enameled jewelry inspired from myths and fairy tales. Drawn primarily from animal references and motifs found in ancient Greek, Oriental and American Indian sources, her finely detailed bracelets, rings, and pendants are carved in wax; often with the aid of a magnifying glass, then cast in 18k gold. Though most enamel work is usually fat, Davidson's work is quite unusual in that the enamel surfaces of her rings and bracelets curve around the edges, creating a subtly sensual more 3-dimensional form.

In sharp contrast to Davidson's intricately carved pieces are the stark, highly stylized brooches and pins by Abrasha, a new face to the Philadelphia show. These minimally structured works are created from unusual combinations of materials including a computer hard disk with oxidized sterling silver, and 24k gold, a porcupine quill, and a naturally colored diamond, plywood coupled with 18k gold, rubber, sterling silver and 24k gold, or 18k gold, a diamond, and beach pebbles. Strange couplings indeed; but they are very successful in the subtlest of ways. Most of the pins and brooches are basic shapes - a square, a rectangle, or a circle. The size of the flat, 2-dimensional squares are tiny - barely 1½" - all made from the more unconventional materials such as rusted steel, rubber, or plywood. But in the center of each square is a small slit, rimmed and studded in a precious material, offering a minimalist statement of elegance.

Another artisan working in a minimalist vein was Joan Parcher whose bracelets, necklaces, and earrings were superbly crafted pieces based on architecturally simple shapes. The clean lines provided a strong base for the precious materials she incorporated into her pieces: a bracelet made from matte-colored, enamel-on-copper discs hung from an oxidized sterling chain; a pair of earrings, each formed a classical S-curve in oxidized sterling with a tiny 24k vermeil star burst dropping from the tip; a starkly defined necklace composed of a single length of stainless steel cable with one end terminating in a small square, and on the other end a tiny, 23k gold leaf over sterling cube that dropped through the middle of the square to close the loop. Parcher, who is new to the craft exhibition circuit, showed work that revealed both a remarkable purity of design, with an unusual use of materials.

Turning from unadorned minimalism to more earthy designs inspired by nature, two exhibitors of note were Valerie Mitchell and Betty Helen Longhi. Mitchell's work, which is extremely sculptural, conjures up exotic plant forms, roughly executed in copper with colors that enhance the organic nature of her designs. Although the pieces look heavy, Mitchell uses eletroforming to create hollow shapes that are actually rather light. Some of her pieces are treated with mixes of raw chemicals or enamels creating antique-looking surfaces of henna, verdigris, and ocher; others consist of sterling silver covered with 24k gold vermeil. Mitchell's necklaces and bracelets translate the natural, raw beauty found in a seed pod, a small plant form, a twig, or a leaf into a very personal statement.

While Valerie Mitchell's works speak directly of natural forms, colors, and structures, Betty Helen Longhi takes the curvilinear forms found in nature, and translates them loosely into more decorative Art Nouveau-like designs. Using niobium to enhance the flowing lines that feed into one another, her brooches echo movement through space. The combination of die formed, forged, and anodized 18k laminate with the niobium creates a fluidity of motion.

From inspirations found in nature to inspired whimsy there were several exhibitors whose work took a decidedly different spin. Cleverly combining sterling silver with laminated acrylic and, in some instances, adding semi-precious stones such as garnet, amethyst, citrine, and peridot, Gina Chaplain created fantastical spoons, "blush" brushes (makeup brushes), and bottle stoppers. These pieces were expertly fabricated with sterling silver storybook and imaginary characters mounted on their tops, and bands of boldly colored acrylic creating the handles. Walking Fish bottle stoppers, cast then fabricated in sterling silver, were designed intricately down to the most minute detail. These pieces were delightfully different, never silly, and they provided playfulness and fantasy, carefully juxtaposed with a touch of elegance.

Equally as whimsical but indebted to the Memphis and Post Modern styles were Mardi-Jo Cohen's earing utensils. Made from combinations of Formica, silver, acrylic, nickel and semi-precious stones, Cohen's pieces were architectural; their boldly colored, patterned handles suggested that a fitting home might be on the top of a table designed by Ettore Sottsass.

Designs for the tabletop are becoming one of the most collectible segments of the crafts market. Many of the exhibitors displayed vessels and other utilitarian objects side-by-side with jewelry and other wearable objects. Even in today's world of fast-paced, take-out dining, and disposable eating implements, there appears to be a trend toward collecting one-of-a-kind and limited edition pieces for the home. Based on the number of tableware and related objects shown and sold at the Philadelphia show it would appear that a great many people seem to be very concerned with how they serve and present their food.

Robert Farrell's simple curvilinear forms, many with hammered inlay on the handles as surface embellishment, reflect this view. Using sterling silver, 18k and 24k gold, copper, shakudo, shibuichi, nickel, and brass for his utensils, he creates artifacts that are equally elegant and functional. Using traditional techniques, primarily hollow construction, Farrell incorporates these various materials for their rich color contrasts. His imagery is simple and relies on the subtle, natural curves of palm fronds and other tropical motifs.

Similarly understated in design were the pewter vessels by Jon Michael Route. These one-of-a-kind and limited-edition pieces (including candlesticks, salt and pepper shakers, and vases) exhibited a solid, sculptural quality with emphatic lines and delicate surface patterns.

It was impressive to see such a high level of quality. The artists revealed an extraordinary depth of knowledge of the variety of mediums used, and their capabilities were reflected in the many innovative methods of handling and manipulating materials. It is rare when such a broad spectrum of interpretative styles, vocabularies, and provocative directions within the field of metals and jewelry are found in one exhibition.

Dorothy Spencer is a writer who resides in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania.

Sue Amedolara A Study of Nature: Ornamental Metalwork and Jewelry

McDonough Museum of Art

Youngstown, Ohio

September 7 - October 9, 1993

by Matthew Hollern

An exhibition may be impressive; yet, not provocative, and such may be the case in shows of ornamental metalwork and jewelry. Ornamental works often evoke keen interest and examination, only to lead to an immediate understanding and acceptance. There is appreciation of the design and its execution, but little more, and while the importance of good design and fabrication are not in question the role of the artist as commentator, interpreter, or pioneer is seldom considered in assessing this type of work. Yet in a highly advanced society, capable of extremely refined mass-production what place does the handmade functional object hold? The frontier continues to be the generation of new designs, new interpretations, and stylization of our world's tired inspirations.

A Study of Nature: Ornamental Metalwork and Jewelry, is an ambitious exhibition that includes 35 works in sterling silver ranging from rings to vessels and small sculptures. Sue Amendolara was inspired by the jungles of Ecuador, South America in the spring of 1993 when she traveled the Amazon river Basin in a dug-out canoe. The majority of the work produced after this experience is an elegant refection of exotic natural forms from the jungle. Her use of alternative materials such as bone, coral, wood, and fossil brings color, ornament, and life to her jewelry. A series of 3 brooches, Vannus (a wing), Adamas (adamant or unbreakable), and Aegyptus (of Egypt) are among the most compelling. They remain true to their sources with careful attention to the volumes and relationships found in living things. Adamas is a vertical spike-form of low volume, inset with bone and karat gold bezel. The head of the form is punctuated by an almond shaped coral cabochon, karat gold, and a beautiful file-cut sterling surface. Vannus and Aegyptus, similar in form, share rich surfaces and include coral and fossil dinosaur bone. The refinement and symmetry of the brooches lend to their formality. Jungle Brooch II composed of several low-volume hollow constructions reflects the varied shapes of tropical plant leaves. Sterling and karat gold are played down with finely cut surfaces and convey the qualities of living tissue and growing forms. The arrangement of leaves remains faithful to natural patterns of growth. Flora Necklace is the most enticing piece of jewelry because of its contrasting qualities of elegance and aggression. The necklace is made up of a repeated shape, with a thorn lacing out and off the collar, tipped in 24k gold. Among the non-jewelry objects two sets of tea spoons draw upon their jungle sources with great success. The business end of the spoon could well have been inspired by a dug-out canoe while the handles seem to attach and grow like a palm frond from its main stem. The spoons are no more than five inches in length which amplifies the full round volumes of the handles. Jungle Vessel and Jungle Tree are larger ornamental pieces ambitious in scale and complexity. Yet their construction and execution does not do these designs justice. Where low-volume pillow forms have successfully served in a number of pieces as leaves and stems, the jungle vessel has pillow forms and thin sheet for leaves, not in keeping with all of the other volumes. Thin edges and imperfections in joints detract from the consistent use of volume and fine craftsmanship. Of the larger pieces Flora, a scent bottle, is the most faithful to form and volume. A full fruitlike body sprouts voluminous leaves with the completeness and persuasiveness of the brooches and spoons.

While the exhibition does not politicize or debate the Amazon jungle, the work successfully reflects the beauty and fascination that the artist experienced in the Amazon River basin.

Matthew Hollern is a metalsmith and an assistant professor of metals and jewelry at the Cleveland Institute of Art.

Komelia Hongja Okim

Roberts Gallery

Towson State University

Towson, Maryland

November 7 - November 24, 1993

by J. Susan Isaacs

Initially Komelia Okim trained in fibers in her native Korea, but when she came to this country more than thirty years ago she changed her area of interest to metals. The works on exhibit, large and small sculptures, vessels and boxes, as well as jewelry, reflect the artist's maturity and skill in both its quality of design and impeccable craftsmanship. The jewelry was made from silver and gold, while the sculptures were primarily constructed of copper, with some additions of gold and silver.

It was clear when viewing the totality of the rather large show, including some sixty-two works, that Okim came to sculpture via her accomplishments as a jeweler. Her sculptures retain a sense of decoration and elegance that connect them closely to the jewelry tradition. This link does not detract in any way from their impact and, in fact, exhibiting the two bodies of work together adds an important dimension to our understanding of her oeuvre as the grace of the jewelry informs the refinement of the sculpture.

In the sculpture Fall Symphony forms are based on nature and the composition is determined by the elegant massing of linear pieces of copper that have been patinated a rich shade of green, recalling the color of fir trees. These elements, arranged in a graceful organization of open spaces, are balanced against figural elements that are leafed with gold, combining the glowing yellow of the sun with the mysterious dark verdancy of the forest. Another sculpture, Autumn Contemplation, also demonstrates a flowing and sophisticated articulation of landscape references. It too is asymmetrical in design with tree-like elements and golden leaves. The open spaces become the sky, while several organically abstracted figures complete the composition.

Such attention to nature and asymmetrical balance is a hallmark of Asian art and recalls Okim's Korean cultural heritage. During the exhibition, most of the gallery was taken up by Okim's work, however several cases remained filled with antique Asian pieces from the University's permanent collection. Surprisingly, they did not diminish the experience of the main exhibition; on the contrary, they contributed to our awareness of the Asian tradition that informs Okim's art.

The artist's pieces are elegant and stylized. The technical achievement of patinated copper, leafed copper, and Kumboo technique of adhering gold foil to silver evidenced throughout the exhibition, demonstrated expertise combined with lyrical expression and resulted in an extremely compelling show.

J. Susan Isaacs is an art historian who resides in Wilmington, Delaware.

Curtis LaFollette: Master Metalsmith

The National Ornamental Metal Museum

Memphis, Tennessee

October 10 - December 5, 1993

by Jim Buonaccorsi and LeeAnn Mitchell

Each year in conjunction with Repair Days, one of the major fund raising events for the National Ornamental Metal Museum, the museum features the work of the selected guest mastersmith. This year's exhibition highlights the recent work of Curtis LaFollette of Hudson, Massachusetts. The exhibition is a skillful and biting critique of the tradition of metalsmithing, an area of concentration that is often deemed as 'craft' by the art community and never seriously considered in terms of contemporary aesthetics. The work of LaFollette easily dispels this craft/art schism with the subtlety and grace of an artist who has spent the last thirty years developing not only a visual language that works, but a caustic sense of humor.

Director Jim Wallace and his staff deserve the credit for having the foresight to feature the often difficult work of LaFollette. Although the exhibition contains many individual objects, the work has been displayed in an extremely cohesive fashion that provides a unity not often found in exhibitions of this type. One of the most striking features of this exhibition is the multiple levels of address that this body of work investigates. LaFollette leaves virtually no stone unturned in pursuing the issues of both contemporary metalsmithing and art. These issues range from the formal and technical aspects of metal to the address of social and political content.

The work can be divided into several categories that visually bounce the viewer from extreme subtlety to absolute blatancy. The functional/industrial side of LaFollette's work is best embodied in his striking Trolley Tea Set. The idea of the traditional tea set is intact, tea pot, cream jug and sugar bowl, with a luscious handling of sterling silver, brass, black plastic and wood. The only catch is that the set can fit only one way onto the industrial mild steel cart, the forced placement issues a fascist invitation to tea. The technical prowess within the set, juxtaposed with the steel cart, which looks like an ordinary warehouse cart further heightens the visual oxymoron. Other works in this industrial/functional side of LaFollette's oeuvre are Serving Spoons and Tool Bucket and Tea Strainer with Base. In the case of these works, there is an intentional establishment of a dichotomy, the hard contrast between beautiful form and common function, as well as the contrast between precious materials and gritty common industrial materials.

Another area that LaFollette explores crosses the boundaries of craft, art, and architecture. This series of work addresses the ideas of deconstruction, a field of thinking that first emerged as a philosophical dialogue and was quickly subverted to architecture. Delving into deconstructionist theory could easily become a major treatise in itself, so forgive us here for over simplifying. Deconstruction deals with the idea that by taking something apart and putting it back together in a way that apparently reassigns a sense of utility, one can better understand the potential possibilities of the object and its functions; a three-dimensional reverse psychology if you will. LaFollette investigates these ideas with two pieces entitled Deconstructed Tea Pot (study). These works not only deal with the idea of deconstructing form, but also with deconstructing our preconceived ideas of what a teapot is. Both of the deconstructed tea pots are made of heavy copper plate, up to one-quarter inch thick.

The surfaces are marred and marked by the hand of the artist and the act of making, and are devoid of the spit and polish so often associated with the silversmith's tea pot. In these works, the nature of the material exists as primary. In one, the handle is a lawn mower muffler, on the other a field hockey Eagle ball. The combination of fabricated form, found object and implied function move these pieces far into the sculptural realm.

Also included in the exhibition are 11 xerographs. These are a sarcastic compilation of images and text that address a range of social and political issues. These are intentionally temporal images that become indicators of time and place. One image entitled Second Coming superimposes the McDonald's logo and golden arches upon a copy of an antique etching of Jesus distributing the loaves and fishes. The text with the image reads "McJesus is coming, 5000 served in a single day". Another xerograph in which the text is the title is Tests show no progress in a competitive world. In this image a hand holds a globe of the earth, human silhouettes float aimlessly in space around it while a hooded Klansman looks on. Other xerographs have titles such as Papal Gino and Baby Boom. These are tough images and potentially offensive to those who lack a sense of humor.

The most important and controversial body of work in the exhibition is LaFollette's Euthanasia series. This body of work, like the xerographs, are loaded with black humor. Many find this work difficult because LaFollette objectifies death and the potential ritual associated with it. LaFollette approaches the concept of suicide in a casual, existentialist fashion that mocks not only the medical profession, but virtually all moralists. One of the most unnerving things about these objects is their ability, if so chosen, to be totally functional. Here again, the objects are beautifully fabricated, and the juxtaposition of precious metals against small animal skulls and bones propel these works into the world of applied philosophy. Euthanasia Cup and Coffin is an exquisite example of this work. A small rodent skull serves as the handle for a twisted sterling silver stem and cup. The cup which cannot stand upright on its own also comes with its own sterling silver coffin storage case. Another strong piece in this series is actually a grouping of two Euthanasia objects and a xerograph existing together as a cohesive wall piece. To the left is a small silver and bone cup, to the right, a small glass poison vile with lead cap, in the center is a concrete poetry xerograph entitled Resolute. There are several other Euthanasia objects in the exhibition that display the same level of brutal elegance.

Curtis LaFollette: Master Metalsmith is the type of exhibition that both the craft and art communities could use more of. The combination of consummate skill and loaded content is refreshing in this neo-minimalist phase that both communities seem to be embracing. While beauty may be in the eye of the beholder, intellect remains constant in the work of Curtis LaFollette.

Jim Buonaccorsi is a sculptor and Assistant Professor at the University of Georgia, Athens. LeeAnn Mitchell is a sculptor and independent curator and consultant.

Contemporary Australian Hollow Ware

NIU Gallery

Chicago, Illinois

September 10 - October 9, 1993

by Lynn Whitford

It is an uncommon pleasure for people who appreciate the ancient craft of hollow ware to find so much by so many artists as is included in this exhibition. Initiated by Johannes Kuhnen, Lecturer at the Canberra Institute of the Arts, and curated by Daniel McOwan for the Hamilton Art Gallery, Contemporary Australian Hollow Ware toured in 1992 and traveled internationally to sites in North America, Asia and Europe.

While any distinctly Australian character in the works was not obvious to this reviewer, the influence of European sources and traditions was clear, not surprising considering that 5 of the artists represented were born in Europe and nearly half included in the exhibition have done at least some studying there.

Most of the work was traditional hollow ware in the sense that it is beautifully and durably crafted and functional. Most (but not all) of the objects appear to be intended to be used, if only for special occasions. Though clearly descended from historical silversmithing the works evidenced a variety of different forms and the use of many materials in addition to silver.

One of the most interesting applications of a modern material is seen in the titanium work by Mark Edgoose. His use of this intractable material in hollow ware is masterful, and his handling of color is both atypical for titanium, and very beautiful, especially in combination with other materials, e.g. fine silver, niobium and stainless steel. A number of the pieces make use of aluminum (e.g., cut and brushed industrial aluminum by Andrew Last, anodized aluminum in combination with silver and black granite by Johannes Kuhnen, and raised and powder coated aluminum by Robert Foster). Robert Baines has combined precious materials (gold and silver) with remnant foil (recycled cans) in his ceremonial objects, and Chris Mullins combines black chrome very beautifully with patinated brass.

There are several visually simple pieces in the show which I found particularly satisfying because they were such boldly generic shapes, but subtly distinctive and exquisitely finished. These included the pierced silver plate, vase, and wine cups by Marian Hosking, the raised silver and black anodized aluminum mesh vessels by Susan Cohn, and the silver double skinned bowls with undulating rims by Chris Mullins.

What the show is not is particularly self-conscious about "the art dialogue". It is not art about art. That there is a place in the 20th century for the precious hand-made object (precious in time and craft, if not in material) seems to be taken for granted. These vessels are alive and well, not de-materializing or self destructing, nor commenting on themselves. It is certainly a show which can be enjoyed by people who know nothing about the materials or processes involved.

Most of the artists whose work is in the exhibition are teaching at least part-time in Australia. It will be interesting to follow their work and that of their students in future exhibitions from down-under.

Lynn Whitford is a metalsmith who lives and works in Madison, Wisconsin.

The Arts and Crafts Movement in California: Living the Good Life

The Oakland Museum

Oakland California

February 27 - August 15, 1993

Renwick Gallery, Smithsonian Institution

Washington, D.C.

October 7, 1993 - January 9, 1994

Cincinnati Art Museum

Cincinnati, Ohio

February 18 - April 17, 1994

by Matthew Kangas

In a major museum survey of the California Arts and Crafts movement (1880 - 1920), outgoing Oakland Museum curator of crafts and decorative arts Kenneth R. Trapp has commandeered a wide range of objects which, in turn, are discussed by a group of scholars specializing in landscape architecture, architectural history, historic preservation, material culture, and the decorative arts.

In a region of the U.S. often derided as superficial and dominated by popular culture forms such as the motion picture industry, this exhibition and catalog make a strong case for a high level of artistic and cultural achievement early in this century. True, this achievement was often tied to mystical philosophical systems and the openness to these systems characterizes California today, as then; yet, the great number of works of art, architecture, and decorative arts hat these seekers for new lifestyles and untried moral or metaphysical pathways bought and/or commissioned still merit scrutiny and analysis.

Among these works metals played an important part. Ceramic artist Ernest Batchelder helped Douglas Donaldson make an electrical lamp in 1908. Donaldson set opalescent glass into his pierced-copper shade. In Pasadena, an early center of activity ex-Gorham chaser Clemens Friedell created a gorgeous 107-piece hollowware dinner service for millionaire Eddie R. Maier. In other works for the new carriage trade, Friedell made elaborately chased pieces like Trophy Vase, c. 1915, and Coffee Service, c. 1910, in which the design was hammered into the surface with blunt tools. As Leslie Greene Bowman points out in her essay, "The Arts and Crafts Movement in the Southland": "such work could exceed the cost of the silver". Friedell's punchbowl and coffee set won a gold medal at the 1915 Panama-California Exposition in San Diego.

Donaldson also won a gold medal, for his repoussé and enamel covered chalice which was later acquired by Harvard University. Both the chalice and a Tea Caddy from 1915 of silver crowned by red carnelian stones display his multiple skills as an enamelist, silversmith, and jeweler.

Porter Blanchard brought a more austere New England style to the Southland after apprenticing with his father in Gardner, Massachusetts. This equipped him to make the transition to Art Deco in the ensuing decades in which no ornament at all was used.

Charles Frederick Eaton and his daughter, Elizabeth Eaton Burton, used their considerable fortune to create, commission, and propagate the Arts and Crafts esthetic at his estate, Riso Rivo, in Montecito, near Santa Barbara. Pere Eaton combined "honest Furniture…made by hand" with jewel-encrusted leather-bound books, tooled leather chests, and silver caskets. A patinated repoussé tin Tea Screen, c. 1901, includes windowpane oyster shell for the sky above a California landscape. Bizarre but beautiful, his daughter's electrical lamps and hanging shades incorporated coastal seashells and mica into hammered and pierced copper shades.

In his discussion of the Bay Area, Trapp offers a model of historical scholarship and a paradigm of curatorial detective work. The project took nearly seven years of tracking down and authenticating appropriate works. After the Oakland Museum exhibit opened last February Trapp continued to receive crank and crackpot letters from people living in period homes completely furnished with Arts and Crafts furniture, pottery, metals, and textiles. Like every other originally healthy and progressive movement, California Arts and Crafts has by the 1990s degenerated into a possessive, nostalgic cult. All the more credit, then, to Trapp and the lenders who agreed to share their treasures.

The San Francisco Guild of Arts and Crafts was founded in 1903 by a metalworker, Douglas van Denburgh. The city was already the major manufacturing center in the West and supported a number of craft industries. Paul Elder and Co. was an important outlet for fine goods which included brass work by van Denburgh and Victor Toothaker. Shreve and Co. had already been founded in 1852 and, significantly, was around during both the 1848 - 49 Gold Rush and the 1859 discovery of silver at the Comstock Lode. As a result, particularly beautiful works using both gold and silver were made. Coffee Server, c. 1900, used 18k gold-plated brass over a medieval form with ivory straps on the handle to temper the heat from the beverage. Water Kettle and Stand, c. 1900, employed hammered silver and ivory to the same effect.

Other silversmiths active in the Bay Area early in the century were Lillian Palmer (who later studied in Vienna) and D'Arcy Gaw of San Jose who had trained at the Art Institute of Chicago. The role of women in the Arts and Crafts movement in California should not be underestimated. Lucia Keinhans Mathews, for example, was deeply involved with her husband, Arthur, in their Furniture Shop which sold carved and decorated wooden furniture in the Arthurian style. Gaw designed for Dirk van Erp who opened his Copper Shop in San Francisco in 1910. It remained in business until 1977. As one critic wrote early on: ". . .the output of the shop is staggering in its quantity which is no doubt the reason that the quality of craft and design varies from the mundane to the spectacular."

With over 200 works on view, metals do not dominate The Arts and Crafts Movement in California but neither is the period conceivable without their presence. The range from clunky hinges to effete and precious containers suggests both that the claims for simple style were overstated and that the latitude for material treatments was much broader than generally recognized.

With its curious mixture of progressive idealism, political reform, and high-end production, our nation's first modern crafts movement reminds us that similar principles were behind the post-World War II crafts revival which reached an apogee in the 1960s.

The success of the earlier political reforms, coupled with more widespread training systems for artists, and a broader affluence of potential consumers made the West Coast hospitable once again to fine handmade objects, as well as to the 'granola - street-fair' variety. Why California now has so many excellent artists working in craft materials, including metals, is thus partially explained by this thorough watershed exhibition.

Matthew Kangas is an independent art critic and curator in Seattle.

Julia Barello: Adornments

Graham Gallery

Albuquerque, New Mexico

November 13 - December 18, 1993

by David Staton

Julia Barello gets under your skin…. and into your head.

Barello's Adornments, an installation at Albuquerque's Graham Gallery transformed the downtown gallery into a space of contemplation, connections and conundrums about the human body.

Five turn-of-the-century surgical diagrams were hung from the gallery's ceiling, seemingly floating in soft, golden light above Barello's jewelry. The works mirrored the incisions depicted in the pictures. The sterling silver brooches, bracelets and necklaces, plated in 24k gold, appeared to have been directly lifted from a body; arteries, muscles and capillaries provided surface depth to the contours of the human shape. Texts describing how to wear the jewelry/adornments were displayed atop the pedestals holding the pieces. These instructions shared a completeness and conciseness of language with to-the-point medical texts.

With exacting precision Barello set up a compelling push and pull between the objects of Adornments that holds viewers in its gravity. The dynamic of the jewelry (sculptures in miniature,) and the medical texts (exacting works of lithography) generated a swirl of ideas. What is shared between objects that rest on top of our skin and those that lie beneath the dermis? Does the gold-plated adornment hold more aesthetic appeal than the flesh and blood that lie beneath? If beauty is skin deep, why do we go to such incredible lengths to cover it with objects such as those Barello has created?

These finite questions lead to bigger issues concerning the body as object. Everyday folks tend to think of the body as a whole, commonly disregarding the separate and individual wholeness of the organs, muscles, and tissues that form the big picture. But those in medical professions take a different view of the body; for them, it is a system of interrelated parts. Adornments sets about to both foreground and unify those two disparate views. By isolating the individual pieces, and showing them in a different context, Barello's work challenges viewers to think of the whole from a new perspective.

Adornments also worked from a purely physical standpoint. The surgical diagrams demonstrated what lay beneath the surface - like those nifty color separations of animals you find in encyclopedias - but you can't touch and feel the illustrations. The jewelry on the other hand, provides that visceral contact, whether it's held or worn. And Adornments offered an uncommon reminder of the intricate interior beauties of the ultimate machine - the body.

What's best in this intriguing installation is Barello's response to questions about the primacy of the image. Where did the object or image come from? That is a question artists are continually exploring. Adornments suggested that the answer comes from within and is lurking just beneath the surface. The inspiration, after all, can be ourselves.

David Staton is a freelance writer living in Corrales, New Mexico.

Gina Westergard The Point of Balance: Pendants and Sculptural Displays

Grossmont College-Hyde Gallery

San Diego, California

October 25 - November 19, 1993

by Carolyn Springer

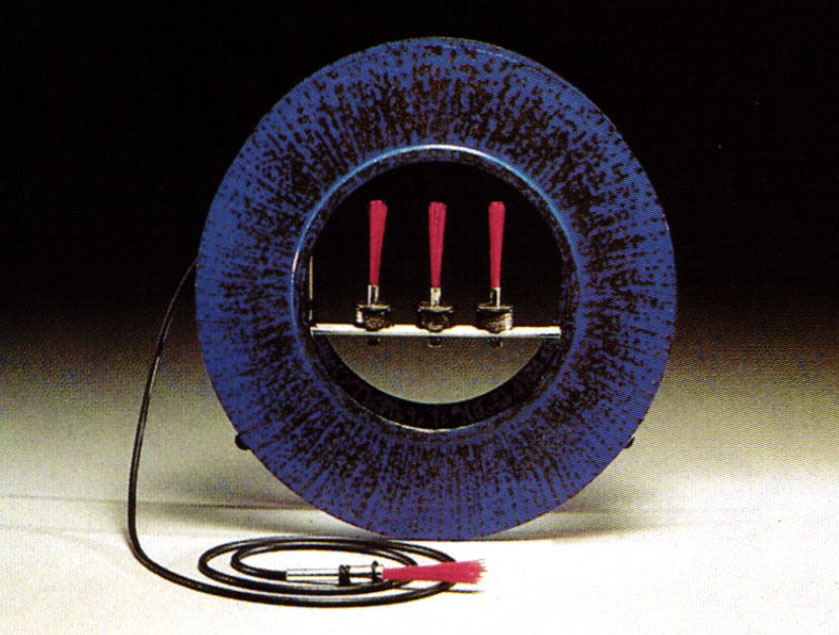

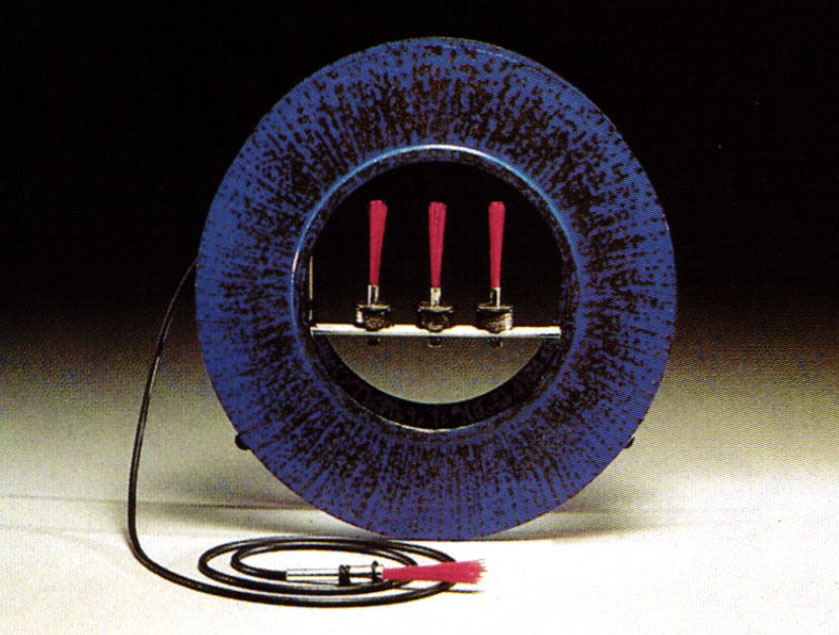

The bold yet elegant work shown at the Hyde Gallery in The Point of Balance, reveals a desire to balance the refined in design with the enigmatic in function. Juxtaposing silver to neoprene rubber, gold to goat hair, and semiprecious stones to plastic, Gina Westergard creates pendants and their sculptural stands that visually excite and puzzle the viewer.

The pieces all explore the potential of jewelry making, yet it is the way in which the pendants interact with the stands that create the often mysterious-looking objects. Some are reminiscent of toys: the top, wheel-o, yo-yo, and gyroscope, while others appear to be sophisticated instruments for science or medicine. It is this invented gadgetry that captures the viewer's interest and invites playful participation with the pieces.

Within Aladdin's Pendant and Saucer Top, Westergard combines pewter, magnets, monofilament, neoprene rubber, and silver to create a refined symphony between traditional hollow ware metalsmithing and unexpected mixed media and machine parts. Magnets are used in the piece Rock and Slide and as the sculpture rocks back and forth the magnets slide within it. The magnets display a playful, quirky character but eventually settle back to a center point when the stand becomes still. Westergard's interest in kinetics and use of magnets in the work reveals a deeper search for content and explores the idea of constant balance. Toying around with function, Westergard enjoys the mental exercise that is involved as she resolves the works.

The spherical forms in the pieces suggest the artist's interest in the tradition of metalsmithing and her training at San Diego State University and Indiana University respectively. The repetition of the sphere, egg, or circle as a connecting theme, is a constant part of her design sensibility and helps her to achieve a result in which nothing is extraneous. Achieving universality the sphere is the primordial form containing the possibilities of all other forms through motion. It is a personal symbol for the artist representing the cyclic movement of renewal in life.

Westergard is interested in creating jewelry that radiates life because of the relationship it has with the human body. A wearer's touch allows for a connection and intimacy not possible in other art forms. The pendants, when worn, hover above one of the seven chakras; the spiritual and psychic energy centers in a being. When the wearer is moving, the pendant gently bounces from the chakra point and serves to remind the wearer of being centered and balanced.

Most of the necklaces are very minimal and made up of a single strand of neoprene or a solitary chain and a center pendant design. The combination of pendants and sculptural stands create mysterious objects, whose function is so enigmatic, that the viewer often needs to be assisted in order to locate the necklaces. Rocking Vertebra, which is constructed of many linear, golden hour glass-shaped links, refers to a suspended spinal column and displays the idea of equilibrium between the chain and stand. In this age of holistic healing and achieving balance through yoga and meditational activities, this piece is a wearable reminder of the personal work that one does to achieve wholeness. Westergard states, "The common thread in my work is balance, whether it be in a physical sense of steadiness, a philosophical approach to balance in one's life style, or an aesthetic notion of symmetry between materials and between design and function."

Her work is at its most powerful in its presentation as a mysterious object with movable and removable parts. It is then spiked with intrigue, mystery and whimsy and is allowed to be sculpture, a scientific instrument, a vertebra, or even a refined toy.

Carolyn Springer lives and works in San Diego, California.

Canyons Recent work in Metal by Tim Lloyd

Carleton Art Gallery, Carleton College

Northfield, Minnesota

October 14 - November 15, 1993

by Karen Searle

Landscapes are a primary inspiration to metalsmith Tim Lloyd. Whether in the environs of Lake Superior or visiting the Southwest, he soaks in the colors, contours, and textures of geological formations and the natural history, distilling and reinterpreting them through silver and gold into exquisite sculptural brooches and necklaces. Most recently he has created a group of shrine-like pieces evoking the colors and textures of the New Mexico landscape where the artist spent several months last year. He was inspired by particular canyon walls and rock formations, ancient cave pictographs, and the artists who made them.

The Canyon Series is more fluid, less contained than Lloyd's earlier landscape works based on mesas and on Lake Superior; the metal forms are thin and embellished with slender rods and tubes. Lloyd makes sparing and effective use of the Japanese alloys shakudo and shibuichi. Traditionally used in Japan for making spiritual objects, touches of these unusual and delicately-colored metals enhance the reverential quality of the pieces. Their matte surface contrasts with the polished silver or gold of the basic forms.

The collaged brooches are small silver and gold shrines to sacred places. Curved forms with tapered ends, and textured with irregular rock-like surfaces, are the basic elements used in pieces such as Barrier Canyon Variation. Restrained touches of color from silver-gray to blue-green are brought in with the Japanese alloys, and suggest offerings in the shrines. Small details added from sliced silver tubes are further suggestions of rock formations. Many of the parts are bundled together with wire. Lloyd's reverent use of materials and patinas evokes a sense of age and mystery.

Based on a view from the bottom of Horseshoe canyon, a strong horizontal line is present in many of the canyon pieces. The forms are reticulated for a naturally occurring texture, and several are incised or inlaid with gold, simulating pictographs and ancient message fragments.

The Betatakin necklace series and another group of brooches are constructed of groupings of tubes fused together and partially opened at the ends or in the center. Their intentional asymmetry conveys a sense of playfulness. Color is added with a few carefully selected glass beads and hand-formed metal beads fabricated from the shakudo and shibuichi. This combination of bright and muted colors is a delightful complement to the silver forms and chains.

Karen Searle is writer who lives in Minneapolis, Minnesota.

You assume all responsibility and risk for the use of the safety resources available on or through this web page. The International Gem Society LLC does not assume any liability for the materials, information and opinions provided on, or available through, this web page. No advice or information provided by this website shall create any warranty. Reliance on such advice, information or the content of this web page is solely at your own risk, including without limitation any safety guidelines, resources or precautions, or any other information related to safety that may be available on or through this web page. The International Gem Society LLC disclaims any liability for injury, death or damages resulting from the use thereof.

Related Articles

5 German Jewelers Marketing Strategies

The JCK Show: The World’s Elite Designers

Metalsmith ’89 Winter: Exhibition Reviews

GZ Art+Design 2004 Spots

The All-In-One Jewelry Making Solution At Your Fingertips

When you join the Ganoksin community, you get the tools you need to take your work to the next level.

Trusted Jewelry Making Information & Techniques

Sign up to receive the latest articles, techniques, and inspirations with our free newsletter.