Metalsmith ’89 Summer: Exhibition Reviews

29 Minute Read

This article showcases various exhibitions in the form of collected exhibition reviews published in the 1989 Summer issue of the Metalsmith Magazine. This features J. Fred Woell, Pat Flynn, Leonard Urso, Robln Qulgley, and more!

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

J. Fred Woell

C.D.K. Gallery, New York, NY

January 10-February 4, 1989

by Linda Norden

Woell was one of the first (and is still the best) among contemporary jewelers to master the subtle art of irony and invest the mundane with a preciousness all its own. It would be hard to name a "fine" artist who has challenged both the material and the iconic shibboleths of bourgeois life as effectively as Woell. I have often thought that Woell stuck with jewelry making—as opposed to, say, sculpture—precisely because making jewelry itself entails a kind of resistance to artworld hierarchies.

Woell has given new life to such arcane forms as the medal and the trophy, for example, by subjecting them to the refined treatment—decorative borders, filigree, meticulous bezel settings, etc.—usually reserved for fine jewels. But unlike Warhol, Woell is passionate about his beliefs—and he has a sense of humor albeit a rather black one. The poignancy conveyed in Woell's "commemoratives" depends just as much on his politically/emotionally charged subject matter as it does on his exploitation of the craft.

Woell's subject matter may give his pieces their reason for being, but his design skills give them their life. When I first saw one of Woell's infamous slide shows, I was overwhelmed by its elegance, by the decidedly un-Kitsch and serene landscapes he offered as examples of things meaningful to him. I mention the slide show because it may offer a clue to Woell's esthetic. Woell's subject matter may often be unruly, or tragic, or angry, and his materials may be intentionally crude, but his settings are almost always symmetrically ordered. Also, many of his pendants and pins feature photographs and conflate the cameras tendency to focus attention by framing its subject with the jeweler's habit of highlighting an important jewel through its setting.

Woell's compositional strategies can also be compared with those of Robert Rauschenberg who has used the camera throughout his career as an artist. Like Rauschenberg, Woell uses a regular, compositional matrix to stage subtle and complex dialogues between literal and metaphorical elements. Rauschenberg often used an image of J.F.K. where in a press-conference pose the President's finger is pointed to emphasize an idea. Rauschenberg used it as a conventional pictorial device, to direct the viewer's gaze to another portion of the painting—a rocket perhaps, or an Olympic runner, or an image associated with the Bay of Pigs—in which he depicted something that Kennedy may have been thinking or talking about.

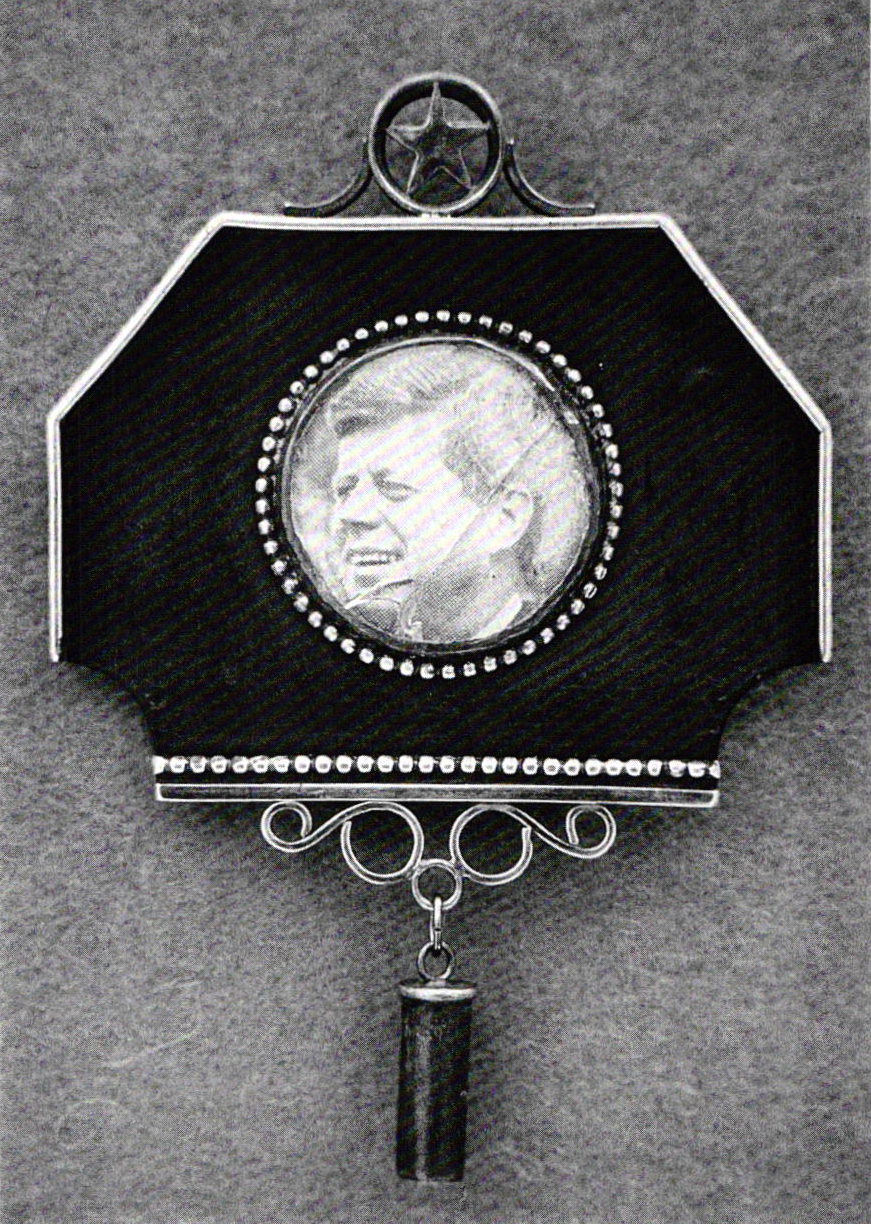

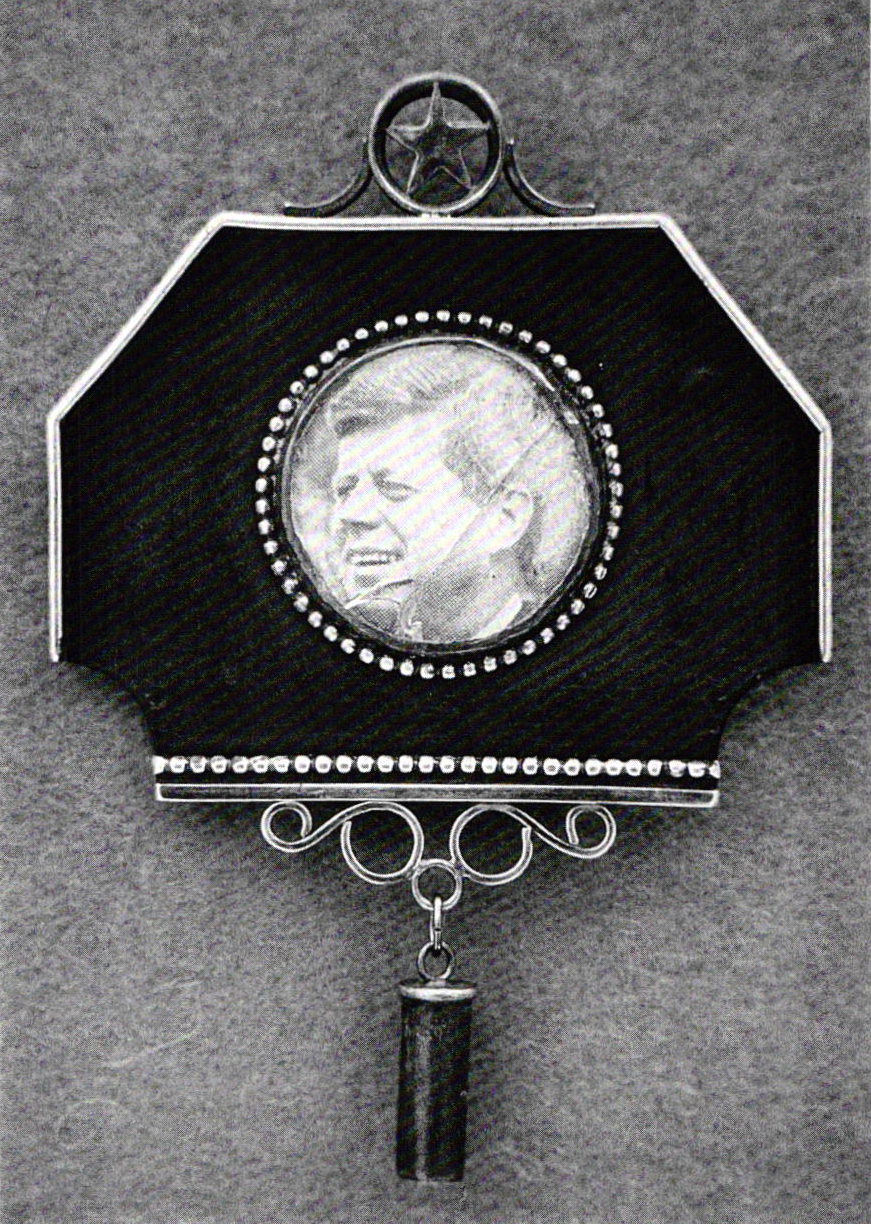

In Woell's tribute to Kennedy, November 22, 1963, 12:30 P.M., of 1962 the reference to time is reinforced by the clocklike configuration of the piece. Multiple entendres abound: the clock's pendulum, or weight, is a bullet shell; the "face" of the clock is J.F.K.'s and is cracked; the decorative element on top and center is a "lone star" the Texas insignia.

To spell this all out, of course, is to dull the impact of Woell's pieces. My point is simply that Woell's jewelry is most poignant when just such ingenious matings between form and content take place—in his early work of the 60s and in the commemorative spoons, for example, and less so in the more generalized pieces of the late 70s. And for all their approximation to sculpture or trophy, Woell's jewelry truly "Comes Alive" on the body.

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

The Jewelry of Pat Flynn

Faith Nightingale Gallery, San Diego, CA

November 4, 1988-January 6, 1989

by Debra Stoner

Although there were 23 pieces on exhibit, only six real "ideas" were present in this show of Pat Flynn's jewelry. There were elegant bar-brooches in ivory or onyx, wrapped with fine silver or gold wire; small, framed, heart-shaped brooches; oval earrings set with round semiprecious stones; a pair of oxidized silver cups with richly textured surfaces; a formal necklace of white and yellow gold, set with a triangular blue topaz and hung on a steel wire; a pair of cylindrical cufflinks studded with stones. The ideas were repeated too often for such a small show, pointing to their source in production thinking.

The production nature of the heart series was obvious in the gimmicks Flynn uses to differentiate one from another. A thick, rectangular, wire frame surrounds a heart shape, whose surface is embellished with wire wrapping or small bits of gold foil or gold sheet. These are left fine-silver white or oxidized to dark gray. One of these pieces would be a lovely surprise but, nine of them points out their production qualities and makes one look even harder for differences that seem significant. All one finds is that every frame is identical, cast from a mold.

Flynn is a fine craftsman. The care in his handling and setting of gemstones shows attention to detail, as do the rich surfaces of his metalwork. One feels, however, no connection with the artist in these pieces. One senses that a clever recipe has been found to create that "Pat Flynn look." This selection of works lacks the edge and vitality that Flynn earlier employed with found objects, such as rusty nails or sawblades, contrasting them with rich gemstones and precious metals.

With the new cylindrical cufflinks set with garnets and using commercial findings (the findings are of a scale that is at least half the pieces!) or the necklace of white gold with blue topaz on a twisted neckwire, one senses that a broader audience will be attracted to this work because it is so. . . nice. But is nice what Flynn aspires to? This new production work will gain Flynn a new audience but, this writer fears that he will lose his more demanding fans.

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

Leonard Urso

October 14-November 15, 1988

Dawson Gallery, Rochester, NY

by William Baran-Mickle

In this exhibition, Leonard Urso's first solo show, the gallery overflowed a bit uncomfortably with more than 50 works of jewelry and sculpture.

Nearly all of the works were handwrought of a single sheet of copper or silver, with a shell-like positive image revealing the figure. Three beautiful figures, three- to four-feet tall, lifting well above the viewer on unimposing aluminum, slate and steel bases, stood in the entry hall. These figures, titled Mystery, Young Woman and Woman, were all well-sculpted images, demure, calm and angelic.

In their motionless, quiet stance, one thigh slightly overlaps the other, the arms disappear to a dark formless background and their faces lift up, cocked to the side, each jawbone strongly delineating the head. These heads then dissolve into an abstract, ethereal or stonelike ground. The length of the outer edge of each woman-form is undulated with glimpses of the metal's thick (¼ inch) upset edge.

There were also figures mounted on walls and lying on the floor. Quiet or Silent Woman, Servant and so forth (there was one Quiet Man), was a series even more stylized than the freestanding figures. In the extreme, they recall funerary markers. Most were blackened with the edges barely reaching their intended forms. Some of these were reduced to abstraction with slight indications of gender. These were less "beautiful" and erotic, though deeply estranging.

Even more extreme than the larger sculptures were the minimalist forms done in 14k and 18k gold, stone and ivory, some sterling silver. Most were earrings and pins, all evenly and lightly textured by machine. Like the Quiet Women that adorn the walls surrounding the jewelry cases, the pins and earrings were elongated, slender forms with only slight indications of a figure. They were simple and appeared delicate; yet, they were without the foreboding atmosphere of the larger works.

The romanticized female figures floating on pedestals, bound to walls and dancing in large bowl forms, had a disturbing presence. These sculptures invoked past works such as ancient Cycladic stonework and the hammered-copper figures of Saul Baizerman in the 1940s. Yet, the meaning of these works remained unclear. The artist's statement claimed "strength and truth of [each] character" as well as "its inner self" in the details and intricacies within each figure. However, rather than these characteristics, Urso gave us a successful study of the idealized female body.

Urso's figural format is limited, successfully perpetuating the status of the erotic or pornographic in our society. Throughout the work, details of the body were generalized. Here, individuality diminishes in direct proportion to societal preferences for anonymous female shapes over a woman's identity. Indeed, these women had no personality, only a vacant mask.

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

Robin Quigley

C.D.K. Gallery New York, NY

November 8-December 3, 1988

by Linda Norden

Robin Quigley's "mature work" does not imply a consistent, recognizable style achieved through years of repetition and refinement, but rather an advance toward a more self-conscious approach, a less literal manner of working.

The 23 pieces on display were disarmingly direct and unprepossessing. From three very modest conceptual notions, Quigley generated a series of rings, brooches, earrings, bracelets and neckrings in gold and silver. Quigley poses a problem for herself and then sets out to resolve the problem formally. She rarely weights these formal problems with references or didactic meanings. But it is precisely because Quigley's claims for her work are so modest that the jewelry itself is so satisfying.

A series of Coil Bracelets that she rendered in various combinations of silver and gold, for example, grew out of her fascination with Slinkies, the slithery children's toy. In the process of developing a more durable version of this fluid coil, Quigley employed a method of generating a complex form from a simple module. She solders individual, imperceptibly curved, hollow cells, end-to-end, occasionally switching from gold to silver (or silver to gold) as she builds anywhere from one to nine coils for the bracelet. The beauty of this working method is that it yields a form at once unique and (apparently) self-generating.

By focusing primarily on the modular aspect of the coil pieces, Quigley generated another impressive series of bracelets called, variously, Starburst, Sunburst and Pineapple. Here, hollow pyramidal units were soldered into bracelet-sized rings to form a kind of open star form. These spiky rings were then stacked to form a regularly staggered surface. As in the coil bracelets, Quigley sporadically inserts a different [color] metal unit while soldering the rings. She also blankets the surface with a subtle "veil' of hand-Florentining.

Quigley's attraction to the Slinky may also derive from her longtime interest in forms that move and, as a corollary, make sounds when worn. In a series of more self-consciously primitive earrings and bracelets, she made some years ago, she achieved this aural dimension by fringing simple geometric forms with bits of hammered wire that rustled delicately as the wearer's body moved. At C.D.K., she pushed this idea of dangling components further in some wonderfully simple wire bracelets and neckrings. Often, one band "swings" from the ends of another-hence the titles, Swinging Ring, Swinging Hoop Earrings, etc.

Quigley's most musical objects were her "bell" earrings. That description might suggest a pair of unwearable weights, which these are not. I'll risk sounding sexist when I say that you have to wear earrings to make great ones, but it's true. Quigley revives the whimsy that characterized so much of her early work by housing tiny clappers and spheres inside elegant, highly polished cylinders and cones. These new earrings offer an extreme example of one of Quigley's most delightful habits — making pieces that seem to have both a public and a private life.

In pieces such as Spiral Brooch and Round Pyramidal Brooch, the back or inside of the piece is not only finished, it functions as a kind of interior to the pin's sculpted facade. Perhaps because they lack moving parts, these brooches, and their accompanying earrings, seem more static and overly serious than the pieces described above. Even so, they reveal the same kind of wonderful surprises in their detailing, as Quigley manages to pay attention to every detail without seeming finicky. More important, both literally and figuratively speaking, Quigley's jewelry seems to be made from the inside out. These pieces don't want to be"—they are.

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

Max Fröhlich, Rena Koopman

Helen Drutt Gallery, New York, NY

December 3, 1988-January 14, 1989

by Lisa Spiros

This exhibition served to contrast two metalsmiths exploration of self-made metal alloys and patinas. Both artists emphasize the esthetic qualities of the metals, one through sculptural interpretation and the other decorative.

The collection of Max Frohlich's work was exhibited to commemorate his 80th birthday. Comprised of largely recent works, with several references to his earlier accomplishments, it was a depiction of his lie as an internationally prominent metalsmith and pioneer of modern jewelry.

A timelessness emanated from Fröhlich's work. The dish and goblet of 1948 is of the same style as his wine jug of 1988. The former, handraised and bronze-gilded, is made from circular forms, delicately counterweighted into ellipses, which also applies to the wine jug, handformed and fabricated of sterling silver. The silver vessel, with its substantial, square base, is gracefully transformed into an elongated triangle at its spouted top. Although they deviate from their geometric origins, they are sleek and minimal in design, classical qualities that make the pieces as relevant to the 1980s as the 1940s.

Fröhlichs current rejection of Bauhaus ideology denies formal geometry and symmetry as a belief system "Logic alone is for me equivalent to the cold spheres of the universe. It is devoid of all warmth and is thus simply freezing." A series of rings from 1985 have a resonance of industrialism yet, here is a departure. Circular contours again become ellipsing ovals, encompassing the fluid movement of rising and recessing metal. The only interruption is a negative shape, centrally added for a strong contrast to the circular movement. The rings are of substantial weight, being solid castings of sterling silver. The wax models themselves are cast from a carved plaster form and then reworked. Never machine finished, the pieces are rubbed with charcoal to give a lustrous surface.

Two groups of work differ from the rest: those incorporating African Ashante casting techniques (inspired by a trip to Africa in 1977 to study the art of native craftsmen) and those investigating self-made alloys (1985-1988) shakudo and shibuichi. In these, Fröhlich makes a complete transition, focusing on surface embellishment. His emphasis turns toward graphic dynamics from pure sculptural form, a move that completes his disassociation with an industrial design esthetic.

Rena Koopman approaches her jewelry very differently, focusing more on esthetic issues. All the work for this show was produced in 1988. Using the Japanese alloys of shibuichi, shakudo and mokumé, Koopman creates a mood in her jewelry reminiscent of abstract painting. The alloys are not merely overlaid, but inlaid into the metal surface. The inlaid, flat shapes establish spatial relationships similar to that of a Japanese print.

Koopman achieves a forceful black with a rokusho patina on shakudo. This is used to contrast with nuanced colors and karats of golds, silver, shibuichi and mokumé. A line is sometimes inscribed revealing a glimmer of light through the patina. This vitality is best displayed in a series of earrings which are delicately crafted and lightweight, allowing for comfortable wearability.

One piece that explores dimensionality a bit further is a bracelet of 18k and 22k green and yellow golds. Here, the planes are broken, then juxtaposed, interplaying against blocks of open space. A pattern is inscribed in certain areas recalling Zen calligraphy.

Overall, the work is decorative, using a graphic antithesis of austerity and playfulness.

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

Helen Mason: Form and Spirit

Delaware Art Museum, Wilmington, DE

May 20-June 19, 1988

by Betty Helen Loughi

The concept of this show arose during a 12-week sabbatical to Japan in 1986. Upon her return, Mason's desire was to produce a body of work that expressed the Japanese esthetic of design and unity while at the same time infusing the works with her own spirit. She decided on the Japanese concepts of enclosure/wrapping, arrangement/pairing, union/tying and collection/bundling. These, she felt, represented Japans cultural link to the past while still appropriate to everyday life in the 80s.

The work was divided into two groups. The first was a series of wrapped boxes, symbolic of Japanese gift giving where the "presentation" is as important as the gift itself. The boxes were made of clay, raku-fired to a deep matte black, then wrapped with black rubber and commercially textured with perforated aluminum that was anodized and dyed to shades of red, fuchsia, green and dusty rose. There was a definite progression to the series. Wrappings I were boxes tightly enclosed with many bands of aluminum and rubber. In Wrappings II, the patterns were more open with a single black rubberband symbolic of the obi sash on a Japanese kimono.

With their simple, geometric patterns and the color relationships of the anodized aluminum mesh intended to evoke the patterns of kimonos, these were the most successful pieces in the series. In Disclosure I, the boxes were larger; the bands were completely removed and decorations consisted of abstract patterns of the perforated, colored aluminum. The final series Disclosure II showed the boxes being opened and their contents (aluminum tubes) becoming more and more visible.

The second group of pieces were studies of tying and bundling. Horizontal Bundle and Vertical Bundle were sheets of hard rubber and anodized aluminum, alternatively stacked and banded together. The outside surfaces were decorated with abstract patterns of the same anodized aluminum used in the box series. A grid pattern was intended to emulate those found in shoji screens, while the checkerboard motif in Horizontal Bundle was related to the Shogun patterns found on castle walls. Other pieces in this series consisted of rubber and aluminum tubing wrapped or tied into large structural bundles. The most dramatic of these was Diagonal Bundle.

In this piece, the heavy rubber tubing was inset at the ends with anodized aluminum tubes representing Japanese scrolls. These scrolls were held together by a wrapping of clear polyethylene tape. The continuous wrapping of yards and yards of this tape gave an image not of the mundane material it was, but of an elegant silk, bordered by bands of rubber formed into wide, flat bows, which appeared more like velvet. It was reminiscent of the obi and, in combination with the twisting, leaning scrolls, it stood as a strong visual image.

In her statement, Helen Mason says, "The underlying theme and my inspiration is the subtle but dramatic expression in modern Japan of the Esoteric forms of unity. . . My goal has been to capture what lies beyond these forms. . . to discover and become a part of the invisible spirit that created them." In viewing the body of work as a whole, I feel Mason has achieved her objective.

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

Verena Sleber-Fuchs

Jewelerswerk Galerie (formerly VO GALERIE), Washington, D.C.

March 1-22, 1989

by Lenore D. Miller

A sculptor at heart, Sieber-Fuchs succeeds spatially with her creations, as free-standing sculpture, particularly when they are displayed on pedestals or draped over tubes. When worn, their nuances of light and shade, rigidity and transparency, tend to flow with the body. As functional, wearable art, some pieces appear more successful than others.

The artist captures and manipulates the viewer's perceptions through the devices of expectation and surprise. Her hallmark is a magical transformation of humble materials into objects of evocative power. An example is Snowgirl, an enchanting fairytale capelet made of sagex (styrofoam) and wire, which, at first glance, appears to be woven seed pearls.

One of her most elegant pieces is a collar of butcher paper and wire. This plasticized paper with a pinkish hue has been cut into small, square pieces and woven together into a continuous fabric. It resembles flamingo feathers as it catches the light and moves in air currents.

Weighty materials like metal beads and wire are used in Three Bonnets, a piece whose construction suggests monumental sculpture. In Head Piece (#6), torn fragments from comic strips are reassembled into a beehivelike object. Upon close inspection, snippets of Mickey Mouse images are discernible. The piece is typical of many works whose cumulative effect masks the identity of its components. Sieber-Fuchs is sensitive to the expressive possibilities of structure, and her art has visual affinities to the works of architects Frei Otto and Felix Candela.

A necklace called Carcere is characteristic of the conceptual slant of much of the work. Its coiled allusion to a snake and the encasement of cherry stones play on one's imagination. It is both benign and terrifying at the same time. Jeder Schmuck hat Seinen Preis! is a whimsical collar that uses scraps of paper torn from jewelry catalogs. Creating an overall pattern of tawny coloration, the word play is typical of early Cubist collages. In many of the works, the artist leaves strands of wire protecting at various intervals, as if to undermine the notion of a continuous structure and engage chance as a design element. The artist views her work as a game, playful yet serious, in which material, technique and form interact with thoughts reflecting daily life.

Ellen Reiben, the new owner/director of VO Galerie, now Jewelerswerk Galerie, expects to retain a similar attitude and follow the same exhibition schedule.

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

Komelia Okim and Her Selection of Young Artists

Plum Gallery, Kensington, MD

November, 1989

by Sandy Kita

This show of work by Komelia Okim and her selection of young Korean metalsmiths presented an opportunity to examine the relationship between a mature artist and her younger contemporaries. Okim attended Ehwa Women's University in Seoul and Indiana University in Bloomington. Although born in Korea, she now works almost exclusively in America. Her very name attests to her internationality, "Komelia" being a combination-created by the artist herself—of the words for "Korea" and "America."

That East and West are inextricably mixed in Komelia Okim, is apparent in her art. On the one hand, she employs such typical western methods of jewelrymaking as anodizing, patination and fabrication, and, on the other she uses such esoteric eastern techniques as keum-boo (gold overlay) and poe-mock saang-gaam (cloth inlay). The end result is like a fantastic stone, split open to reveal flat angular facets, each a different color and composed of such varied materials as titanium, niobium, sterling silver and 24-karat gold. Indeed, at first glance, the skill with which these various metals are combined is the dominant impression.

However, on closer examination, Okim's talent shows itself to be far more than technical. Her work has a natural quality that paradoxically denies the importance of refinement and craftsmanship. In Square Windowscape, the gold foil looks thin and fragile, crinkling much as one would expect it to in one's own inept fingers. The steel in Winter Landscape looks like steel. Neither work denies the nature of the substances out of which it has been formed, transferring an earthiness most appropriate to these pieces, which are, after all, landscapes. However, more importantly, in Okim's willingness to let the material be what it is, there is an ease of manner. This confidence allows her ideas to shine through without overembellishment or unnecessary refinement, giving her work a characteristic that distinguishes the master from the disciple.

This difference is most pronounced in the case of Jung Hee Kim Byun, a graduate of Ehwa Women's University and Idaho State University. Her work, apparently, is an attempt to apply her background in fabric art to metals. Her niobium and silver Kite Pin certainly looks like thread, ribbon and cloth. The craftsmanship is impeccable; the result, both literally and figuratively, is highly polished.

Also in the exhibition are works by Seung Hye Park, who has a B.A. from Ehwa Women's University, and in addition, an M.F.A. from Southern Illinois University, Carbondale. Like Okim, Park uses a variety of different materials and techniques. Her work, too, is highly disciplined and carefully crafted. These qualities can be seen in her A Little Corner in Space, a work that also features a windowlike motif.

Another artist in the exhibition is Jung-Hoo Kim, a graduate of Seoul National University and the State of New York at New Paltz. Her Out of the Window I is beautifully refined—even the pieces of driftwood that appear in these works seem cleaner than flotsam could ever be. In My Rest Place with a Cup the coffee cup of the title sits on a chair by a rain-splattered window—the latter becoming an evocative symbol of something that allows us to view the world outside while separating us from it.

Finally, the exhibition features the work of Eun Mee Chung, a graduate of Hong-ik University and the University of Wisconsin, Madison. Chung, too, is a master craftsman, cleverly using such everyday materials as knitting needles to create the delicate Break Pin, which, seems to address the pangs of the artist who finds herself succeeding in a foreign country. The "break" in the Break Pin is clearly a personal one, and, like Jung- Hoo Kim, Eun Mee Chung has made a common imagery uniquely her own.

If in nothing else, the motif of window is common to Komelia Okim and at least three of these four young Korean artists, but while this connection may be the most obvious, it may also be the least important. More significant in understanding the relationship between an older master and her younger contemporaries is the fact that each of Komelia Okim's select artists is a woman, each is a graduate of an American university and each was already well educated in her own homeland before coming to this country. In the seriousness of these four young Korean artists, there is something, frankly, youthful. In any case, I find their careful work different from the easy mastery of Komelia Okim. And yet, in their very seriousness lies, I believe, an unquestionable promise.

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

Contemporary Metal Vessels

Sarratt Gallery, Vanderbilt University,

Nashville, TN

February 15-March 15, 1989

by Klaus Kallenberger

This invitational metals show included 21 pieces by five craftspersons with very divergent esthetics.

Two attitudes dominated the exhibit: an industrial fabricated look and a mysterious, ceremonial esthetic. All pieces were dark, with few polished or refined surfaces. The traditional mark of craftsmanship was generally abandoned. In its stead was an expressive, gestural quality, which in some cases bordered on the primitive, if not the inept. None of the "vessels' function, other than, perhaps, ceremonially or sculpturally.

The ceremony, the totem or the icon they allude to is encoded and the code is not readable to the viewer. One is confronted with objects totally disconnected from our everyday, consumer-object-oriented reality. The viewer felt as if he has entered an anthropological display of cultural objects without the knowledge or key to attribute significance or meaning to them.

Every piece in the exhibit had a strong presence, mainly carried by its size and an authoritative command of basic design. The "vessels" were conceived with competence, yet no new ground was opened nor did one find anything unexpected. Surface treatment was important to all forms. Much attention was given to patinas, colors and textures. The metal is folded, textured, etched, pierced with slashes and riveted or bolted.

David Butler provided iron altar stands for his folded metal forms, lending them a stately appearance. Lynne Hull emphasized hard, symmetrical and crisp-edged rotation forms. Shari Mendelson's forms were organic, with richly involved surfaces. Claire Sanford's forms were essentially cylindrical, fashioned from strips and bands of patinated metal. This open weave approach stretched the "vessel" concept to more basket than vessel. Pamela Lins crossed into sculpture since her vessel forms were attached to other components, some of them figurative.

No catalog or juror's statement offered any explanation of why these objects were assembled, what was their significance or the intent of the show.

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

Mary Douglas

Sienna Heights College, Adrian, MI

February 8-22, 1989

by Catherine Jacobi

"Our entire linear and cumulative culture would collaspe if we could not stockpile the past in plain view"

- Baudrillard

The form and function of artifice arranges, through the work of Mary Douglas, the groundwork for critical discourse. This discourse, directed by means of western frontier myths, metalsmithing traditions and the labor of craft, reveals the inevitable condition of our nostalgia.

Douglas enters this western landscape in an effort to displace its myths. Within the context of metalsmithing traditions, she aims to dismantle our linear historical expectations. Overt gestures of juxtaposed traditional forms and materials reevaluate the tradition: a porriger, for example, is made of canned-goods tin, or of lead, and a carved masonite TV tray is entitled, Oak Tray. These evaluations, however, become exercises, inconclusive as criticisms.

In a similar format, she proposes a discussion of frontier myths and the labor of craft with a series of plates identified with the Arts and Crafts Movement. Monument Valley Plate, Yosemite Plate and Snake Plate, with their hammered forms and painted landscape motifs, present the conventions for our scrutiny. These belabored conventions alone merely present a reactionary response to our nostalgia by recreating its processes and products. It is not until we can consider beyond what this work appears to attempt and what it actually accomplishes that it will warrant merit.

These pieces, too obvious as individual critiques of the technique and process of a metalsmithing tradition, must necessarily be considered to function beyond this context. While acknowledging a tradition, this work is producing a formulating, not a conforming, discourse. Douglass aspirations for this discourse, to dismantle a "linear and accumulative culture," curiously insure it. Throughout this work, the referencing of forms and materials of past eras becomes a reaction to the notion of nostalgia that fails to strategize. Douglass effort to advance a commentary directed at the labor of craft, is, interestingly, more productive in compiling the labor of mythmaking. Without ever shifting her efforts into a strategy of semiotics. Douglas reiterates the cultural necessity to "stockpile the past in plain view."

The generative path of this work anticipates a more introspective view of the western landscape, a view that would expect to uncover not only the myths but also the prospects of the landscapes labor and artifice. In the stripping of the western landscape (as opposed to Douglas's survey of its surface), the production of a more stratified history becomes possible.

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

Donald Friedlich

Concepts, Palo Alto, CA

November 25-December 30, 1988

by Dawn Nakanishi

The jewelry of Donald Friedlich is a noted contrast to the works usually displayed at Concepts. While most of the gallery's cases exhibit works of highly polished gold and silver, Friedlich chooses not to make his statements with metal. Erosion Series is his most recent and exploratory work. The jewelry is made of geometric slices of black onyx, red jasper, agate and sodalite. There is minimal use of metal or faceted gemstones. Small bezel-set diamonds and simple geometric constructions of gold wire are minute accents. Friedlich focuses on the stone and its surface as a dominant statement.

Erosion Series is a logical title for this body of work. The surface of the jewelry has been carved away by sandblasting, yielding a rich, sculpted relief with a velvety, matte surface. Friedlich selectively controls the depth and shape of an area to be eroded. The sandblasting uncovers the stones irregularities of color natural inclusions and veins. Friedlich's brooches, bar pins and earrings are primarily rectangular in format. He works with the semiprecious stone formats much like composing on a canvas. The compositions are geometric, using triangles, elongated rectangles and diagonal edges. These shapes set up interacting tensions, accented with wire or tiny diamonds.

His most recent works are his bracelets. They are round and cylindrical bangles of black-banded agate. Their overall appearance is black, monolithic and almost machinemade. The geometric patterns eroded into the bracelets humanize the forms. White agate stripes remind the viewer of the material's organic origin. The softer consistency of the white agate erodes at a faster rate than the black, so additional patterns occur. Working in stone presents challenge and discovery for the artist. The bracelets are dynamic because of their size, color and simplicity. Their basic forms bring to mind antique Chinese lade discs or large Chinese cylindrical beads.

Friedlich's most successful pieces in the show were his brooches. They represent an innovative concept of jewelry. Although all the materials have traditional associations, the applications are new and pushed to extremes. Friedlich does more than sandblast texture, he creates a relief of varying depths, sculpting a form. His use of geometric shapes in conjunction with small accents of gold or diamonds is restrained and subtle. The customary bezel "frame" of the stone "canvas" is absent, denying another common jewelry cliché. He communicates with the material's form rather than intrinsic value. The brooches possess a quiet strength because of the spare use of metal. The geometric erosion of the surface appears natural and manmade in the same instant. Friedlich has managed to keep a fine balance between tradition and invention, natural and manmade.

In many ways Friedlich's Erosion Series reminds me of a Japanese rock garden. They are natural, quiet, and contemplative. They are cultivated by human hands but, restrained to insure natural qualities. They are powerful in their simplicity and subtlety.

Review Credits:

- William Baran-Mickle is an M.F.A. candidate in Art History at Syracuse University, a metalsmith and jeweler.

- Catherine Jacobi is a sculptor and writer living in Chicago. • Klaus Kallenberger is a Professor of Art, Middle Tennessee State University, Murfreesboro, TN.

- Sandy Kita is an Assistant Professor of Japanese Art History at the University of Pittsburgh, Pittsburgh, PA.

- Betty Helen Longhi is a metalsmith living in Seaford, DE.

- Lenore D. Miller is Associate Professorial Lecturer in Art and Curator of Art, Dimock Gallery, The George Washington University, Washington, DC.

- Dawn Nakanishi is an artwear, jewelry designer and goldsmith living in California.

- Linda Norden is an art historian, who writes about jewelry and is currently finishing a dissertation on Cy Twombly.

- Lisa Spiros is a jeweler, who also teaches at Parsons School of Design, NYC.

- Debra Stoner is a jeweler living in San Diego. She is a big fan of Pat Flynn.

You assume all responsibility and risk for the use of the safety resources available on or through this web page. The International Gem Society LLC does not assume any liability for the materials, information and opinions provided on, or available through, this web page. No advice or information provided by this website shall create any warranty. Reliance on such advice, information or the content of this web page is solely at your own risk, including without limitation any safety guidelines, resources or precautions, or any other information related to safety that may be available on or through this web page. The International Gem Society LLC disclaims any liability for injury, death or damages resulting from the use thereof.

Related Articles

Fads and Fallacies: Post Modern Collection

Jewelry Design: New York State Artists Exhibition

Colored Gemstone Jewelry Design and Repair

Metalsmith ’93 Spring: Exhibition Reviews

The All-In-One Jewelry Making Solution At Your Fingertips

When you join the Ganoksin community, you get the tools you need to take your work to the next level.

Trusted Jewelry Making Information & Techniques

Sign up to receive the latest articles, techniques, and inspirations with our free newsletter.