Mark Stanitz: Material Evidence

9 Minute Read

The life and work of Mark Stanitz are a study in balances and contrasts. His physical life is lived in a structured, thoughtful and mannered way. His inner world is worked out through his artwork with an unquestioned faith. With the exception of a nine-year stint as a goldsmith living on commission work in North Carolina, Stanitz has not yet required his work to perform commercial duties. Rather, he is moved to create for reasons to be discussed.

By his own admission, Stanitz was not the typical child who passionately played sports or roamed around with a gang of friends. Rather, he was fascinated by the interesting details of his insect collections and the intricacy of gears and circuit boards. However, he focused not so much on the physics as on the invention. His love of detail and creativity provided a balance to an otherwise structured childhood.

Before starting out as a painting major at Kent State University, Mark Stanitz grew up near the Salvador Dali Museum in Cleveland, Ohio. His early paintings were very much in the surrealist style. The construction of designed space and the collection of disparate elements have always been present in his personal jewelry. Stanitz's works are intensely detailed; this practice is simply and solidly a part of him. These recurring details begin to relate together in the same way a dream is analyzed or the subconscious is probed. Literal surrealist paintings re-emerge overtly in his work in a series of small brooches with oil paint on steel in ornate sterling frames (see Landscape with Nude). Intrigued by this re-emergence, he has recently begun to paint on canvas again to see where "it" wants to go.

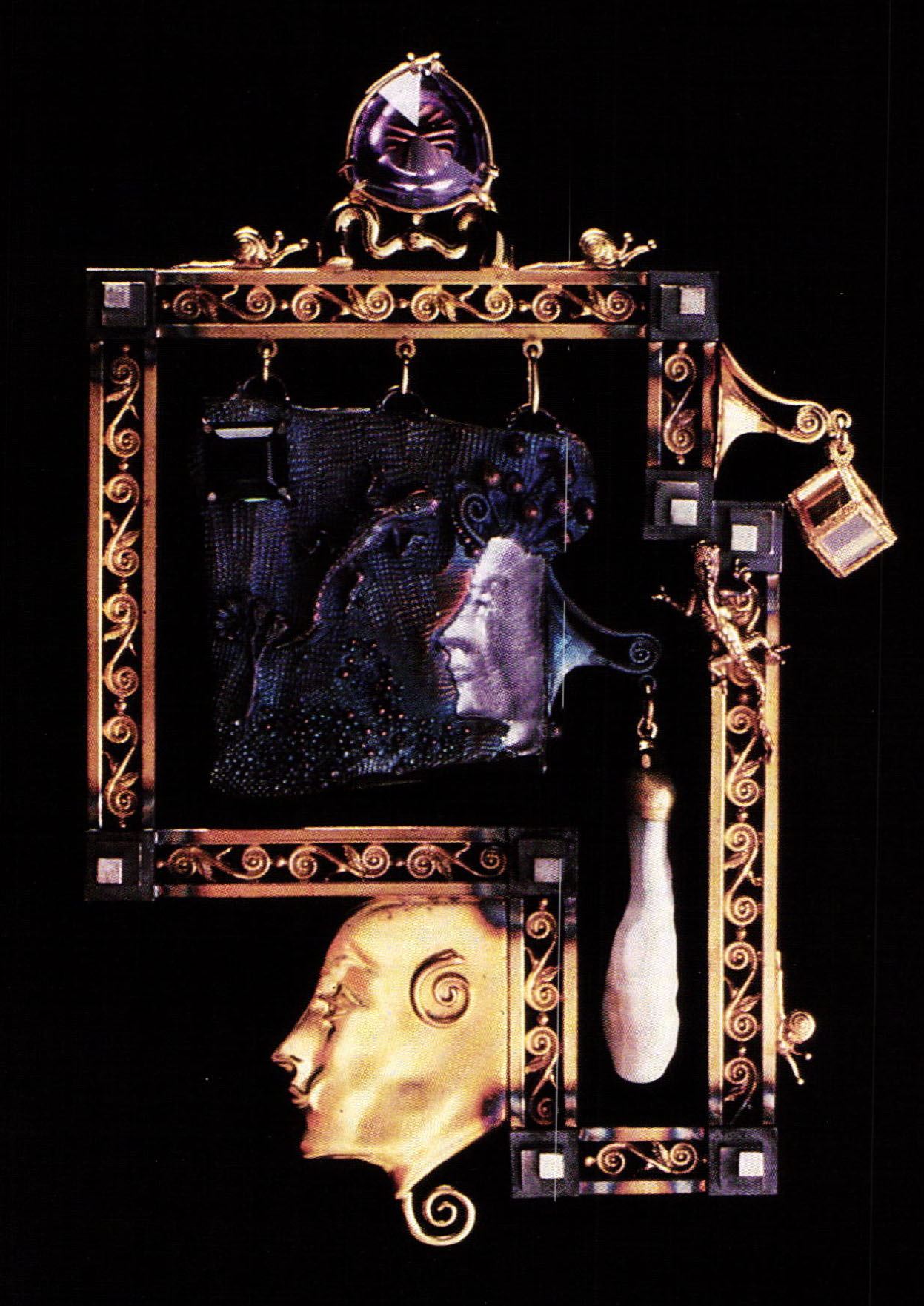

Stanitz's early work provokes wonderment about their narrative. These jewelry pieces were a confluence of influences - Lalique, Fabergé, Dali and Renaissance and Flemish painting - an intriguing combination, to say the least. A closer look at these pieces leads one to a process of locating them in a historical and theoretical context (see Square Wave).

Beginning this exercise, one can see a Renaissance influence in the well-rendered reliefs of the facial profiles and the ornate architectural framing in Stanitz's work. Flemish influences can be found in the numerous little objects from snails and lizards to leaves that, in addition, are depicted in combinations unlikely to exist in a real-time continuum, creating a vanitas of sorts. In order to paint surrealist brooches, for instance, Stanitz used minuscule brushes in a way similar to that used by Jan van Eyck in his Flemish paintings. Overall shape and the larger, general appearance of most of Stanitz's brooches reflect Lalique's art nouveau style. The actual spatial organization of the "canvas" with dangling square gemstones, for instance, is distinctly surrealist in attitude, though perhaps there is a touch of Hieronymus Bosch at work here as well

Stanitz has accumulated a large number of separate images modeled in wax or Plasticine clay and cast in silicone rubber molds which he can reuse at any time. Among them are snails, fish, lizards, leaves, pods, grapes, spermatozoa, amoeba and faces of various kinds, all of which hold meaning for him. The intricate metalwork that combines these elements is reminiscent of the complexity seen in Richard Mawdsley's metalwork. When Stanitz combines his vocabulary, he feels as though he is putting together a poem or perhaps a poetic biography.

Stanitz pays great attention to surface texture, pattern and subtlety. Many of the individual elements and their arrangements are iconic and reflect symbolic images over the ages. Many of these have revolved around the concept of fertility, growth and death.

Beyond these details and influences, it is difficult to say what the work is about or what the maker intends. Stanitz himself can only guess, though his is a more educated guess. This is because, despite the broad range of vocabulary that is his personal language, the story comes from his subconscious, nudged along, of course, by his technical expertise. "I begin with a premise of what a piece will be and have a sense of scale. I begin working and it unfolds much like jazz, impromptu. There is never a question of where it will go next."

One aspect of Stanitz's recent work approaches self-portrait. Roughly two years ago he stopped making jewelry and began making small sculptural boxes. A number of elements from his jewelry appeared on these more sculptural objects, yet the subtexts were pushed to deeper, even urgent, dimensions. Stanitz sees the box as a metaphor for the body. Too small to contain a cigarette, these containers hold the idea of personal meaning, be it hope, courage, oasis or sanctuary. In fact, they could hold a keepsake, a personal relic or symbolic object. To Stanitz, these visually and symbolically heavy walls are the protective facades we use to endure life in public.

These facades are varied in treatment and subject but relate to the topic of the public and private person. The first box Stanitz produced confronted the problematic subject of skulls and skeletons. Ark of the Covenant has a lid rimmed in skulls. The top plate features an adult skeleton in a fetal position holding a baby skeleton. As difficult as many people find this imagery, it should not be mistaken for the nihilistic icons prevalent in heavy metal or other contemporary popular culture. It is seriously based in an older iconography of painting and it's grappling with the seasons of life.

For Stanitz, the treatment of the skeletons on the top plate is akin to an anthropological discovery. These project sites Stanitz has learned to call "levels." Formerly he created a series of wall reliefs by this title, which he clearly recognizes as self-portraits. Stanitz believes his work is prophetic, a claim which can be supported in hindsight analysis of the specifics of his life. In the case of A Box for Your Addictions, the symbolism speaks painfully and directly to a personal tragedy revealed to him soon after completion. A Day in a Life box is also about cyclical changes, here, that of a day. Each panel is an oil painting on steel. The lid section features a dome painted like a globe. Inclination: Plain is visually dynamic and share stylistic affiliation with more playful popular iconic imagery. A reoccurring theme in the boxes and much of the jewelry is the life cycle: fertility and growth and the issues of male-female relationships.

Stanitz sees his father's influence in his work, exemplified in his structured, detailed and fairly unemotional approach to life. He can also see where his mother has added much to balance him through what he calls his "heart side," providing him with "an emotional, personal and fluid center." He embraces this female and male energy in order to create. His need for balance and expression leads him to integrate both sides of his being in his work.

Stanitz recognizes that men and women share traits and that there exists a positive potential for better mutual understanding between the sexes. But he believes that each must locate, understand as much as possible and celebrate what makes each unique. This process had led him to focus on his won maleness in recent works in progress. This does not occur without trials by fire. Indeed, fire is a favorite analogy Stanitz uses to explain his life and art. "The object to me is not the point. Take a fire. The flame and burning, the way you lay it out, the aesthetic are what's important. The ash that's left over is of no consequence whatsoever." His art works are "the evidence of a reality that existed at a point in time that is now forever gone….These are the ashes that are left over."

The object is what is left, like the ashes, after the process. They are the material evidence of his exploration, a snapshot of an experience. For Stanitz, the process is an emotionally free experience he uses to tap into his subconscious, as the Beat poets of the 1960s used free association and stream of consciousness. Stanitz does not draw his work before engaging his materials. Certain familiar parameters are operative, but he does not need to know where he is going. One indication that this process seems to work for him is that, given the sheer number of precast forms he works with, as well as the volume of art historical influences in his work, his objects do not look forced or contrived. Unquestionable technical facility and a large personal language of forms allow Stanitz to merely create.

In his series Level I, Level II, etc., he demanded of himself a more formal or overt participation. As a self-portrait, the central image is taken from his own arm. A familiar ecosystem of parts accompanies the dramatically pointing finger. The charged atmosphere is made literal by the inclusion of an electric outlet. The effect is that of a magnetic field where surrounding spermatozoa, dangling square stones, and snails are scattered in confusion. These reliefs demonstrate a more forceful, directed and conscious art style.

As a matter of coincidence, the process by which these reliefs were made includes electroforming. Molds of his arm and various other details were arranged on a surface and painted to attract copper. The largest relief to date was in the electroplating bath for 21 days. Specific areas were gold leafed, fumed for coloration and then other objects added to the form. This series engages in yet another art practice, one similar to the conceptual realist George Segal. In Stanitz's approach the addition of actual self-impressions allows for a more direct presence of authority and the opportunity for a more consciously probing and revealing tableau of self-expressiveness. The way in which Stanitz's work helps him understand himself and how he relates to a world of men, women and children, life and death, is evident in recent works which have brought him to focus on his own maleness and its relationship to his emotional well-being. As he continues to evolve, so does his work.

- Mark Stanitz has been a professional in the field since 1973 and has taught nearly half of that time. He has been a professor of metalsmithing at the School for American Craftsmen, Rochester Institute of Technology, since 1984.

William Baran-Mickle is a metalsmith and writer living near Rochester, NY.

You assume all responsibility and risk for the use of the safety resources available on or through this web page. The International Gem Society LLC does not assume any liability for the materials, information and opinions provided on, or available through, this web page. No advice or information provided by this website shall create any warranty. Reliance on such advice, information or the content of this web page is solely at your own risk, including without limitation any safety guidelines, resources or precautions, or any other information related to safety that may be available on or through this web page. The International Gem Society LLC disclaims any liability for injury, death or damages resulting from the use thereof.

The All-In-One Jewelry Making Solution At Your Fingertips

When you join the Ganoksin community, you get the tools you need to take your work to the next level.

Trusted Jewelry Making Information & Techniques

Sign up to receive the latest articles, techniques, and inspirations with our free newsletter.