Simple Jewellery by R. LL. B. Rathbone, 1910

A practical handbook dealing with certain elementary methods of design and construction written for the use of craftsmen, designers, students and teachers.

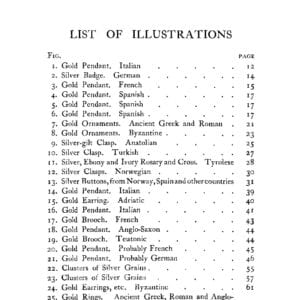

This 1910 book is a hefty 300 pages packed with great information on jewelry history and making jewelry. There are 94 illustrations, both photographs and engravings. The term ‘simple jewelry’ seems to connote what we would call ethnic or folk jewelry today, as well as addressing basic metal working skills for making jewelry. It has the best information around on twisting metal and wire curling for chains and decorative elements.

Chapters include:

A portion of the book deals extensively with design:

The educational point of view, scope of exercises and methods of study, pictorial and sculpturesque jewellery, craftsmanship, examples of craftsmen’s designs, peasant jewelry, designing jewelry, designs inspired by natural forms, the easiest way for beginners, designing by arrangement, the uses of grains, circular forms, theory to practice.

The chapters continue with practical skills:

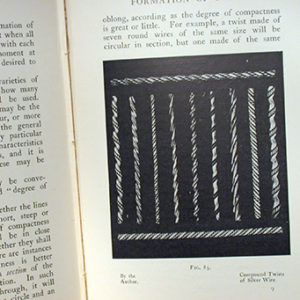

Uses and action of the blowpipe, wire drawing and annealing, coiling wire for making rings and grains, processes of soldering and pickling, details about soldering, constructive functions of grain clusters, devices for making clusters of grains, making and using discs and domes, details about making wire rings, drawing flat wire, how to discover units of design, methods of curling wire into scrolls, an alphabet for jewelers, recording ideas for future use, an inexhaustible source of design motifs, the evolution of design from units, of designing apart from drawing, various kinds of chain, some uses of twists and plaits, more on the uses and formation of twists, samples of twists and plaits, some practical considerations, other ornamental processes, setting and use of precious stones, the question of local industries, mechanical aids to artistic production.

The appendices includes lists of tools, gauges, comparative tables, weights, measure and standards.

The book starts with a discussion about education and how to learn jewelry making. At the time the author bemoans the lack of schools for jewelry making, that mostly it was through the job, or haphazard in hobbyist and amateur training. This book is written at the very beginnings of jewelry and metals being introduced into the educational system.

This extract gives a flavor of the approach:

“The growth of commercialism, moreover, has robbed us of much of our due inheritance in these matters, and in many crafts it has certainly undermined, if it has not absolutely swept away, the whole fabric of apprenticeship. However, it has given us fresh opportunities in exchange, and has imposed new conditions. If it has made it difficult for a youth to obtain a thorough allround training in a manufacturer’s workshop, it has at least done something towards removing the barriers which formerly preserved the mysteries of each craft as impenetrable secrets, only to be revealed to those who were bound by indentures to serve through a long term of years at merely nominal wages.”

The passing of the apprenticeship system is mourned while celebrating the opening of the trade to outsiders, allowing new, not in-the-club people to enter the field. He deplores the restrictions on design that the commercial world creates. The design of jewelry, and its modes are extensively investigated. There is analysis of design elements and composition with a number of rather florid and baroque jewelry pieces. He makes a point that ancillary things like stonesetting, niello, enamel etc can be superfluous to a design, and that a piece should be able to stand by itself without being loaded up with techniques. There is a theme of ideas coming from process that pervades the book.

There are editorial comments about ‘peasant jewelry’ and how making the same thing over and over again can be deadening for the maker. The subtext is a ‘Arts and Crafts Movement” critique of production. There are pithy critiques of jewelry design, strong opinions of what makes for good, and especially bad design. A good third of the book is along these lines, with illustrations.

The new maker is suggested to work with the materials and take inspiration from the working processes. The idea that processes and samples are the letters in an alphabet that the learner makes into words as designs is expounded. The descriptions of metal characteristics and ways of working are poetic and really quite interesting, as the author’s passion shows up. There are some good exercises with granules and with making them. Granulation patterns are really well addressed. Flattening granules to make small discs is a forgotten approach. Jump rings as soldered design elements as well. Great detail on constructing various specific piles of granules to combine into complex pieces.

Then the technical side is dealt with addressing soldering and more. Great instructions on using a mouth blowpipe. Jump ring making is well addressed. There are some odd words, like ‘triblet’ for bezel mandrel, small jewelers anvil is a ‘sparrow-hawk and so on. Soldering and construction are well discussed. There is very good, wise, detail.

Dapping is covered as is drawing wire. Making shapes with pliers, and exhausting all posibilitities of simple work with minimal tools is really addressed very well. The level of description would really help a beginner, where the pressure is on the pliers, how to bend smoothly etc. There are good photos as well showing the subtle stages of what, as jewelers, we take for granted.

There is a chapter on recording ideas, taking wax, carbon paper and plaster molds from wire compositions so as to be able to repeat them. Even soggy cardboard is used to record wire compositions. There is a remarkable picture of 700 variations in bending the same lenfth of wire. A lot of it is about using simple units in repetetive variations. This is a high point of the book, and one of the most interesting things about it, and what the author has to offer. The best published exploration of using simple units I have seen. It is the kind of thing that, like the Kulick-Stark school, which concentrated on granulation and classic chain making, that you could base an entire school, renewed book and hobby workshops on.

There are chapters on chain making by hand, with solid, insightful information. Dozens of handmade chain ideas are pictured and explained. In the same way twists are seriously explored, useful to everyone from blacksmiths to jewelers. This is one of only a few books that explore this kind of information. The level of observation and comment are the deepest I have seen.

There is a section on using repousse and chasing tools to make components. Casting, stonesetting and enameling is touched on.

Finally, he makes a plea that basic jewelry making should be introduced into holiday areas, as crafts to see being made as well as for participants, a kind of economic development suggestion. As well, the disabled are suggested as makers for work in such venues. He reiterates that process is the driving force behind new invention, focusing, paying attention and being in the process to come into new ideas. This is a very modern idea, and early days to have stated it.

The book ends with lists of studio tools and equipment.

A very interesting text, huge, deep, and has information not found elsewhere.

A good bet.

Lewton-Brain 2013

File Size: 50.2MB, 300 Pages