Phillip Baldwin

6 Minute Read

Phillip Baldwin

Now that The Year of American Craft is here, the list of artists deserving immediate recognition and overdue scholarship is long. Each field clay, glass, fibers, wood and metals - has a different set of needs and a different rate in the development of critical commentary.

Within metal arts, there seems to be a division between writing about narrative jewelry - active, seductive, interpretive - and writing about non-jewelry metals such as knives, forged iron, and architectural ornament. Both areas require deep material involvement and expertise. These hard-won abilities of process can often overwhelm the critic's requirements for formal analysis, aesthetic. judgment and evaluation, and interpretation of meaning.

That is, there's so much about the making of a craft/art object to write about that there seems to be little time or space left to write about its context, content, and quality. If there is any one goal for critical writing in The Year of American Craft, it should be to bring the latter qualities into better balance with the former. Meaning and judgement must catch up with process, material discussion, and biography.

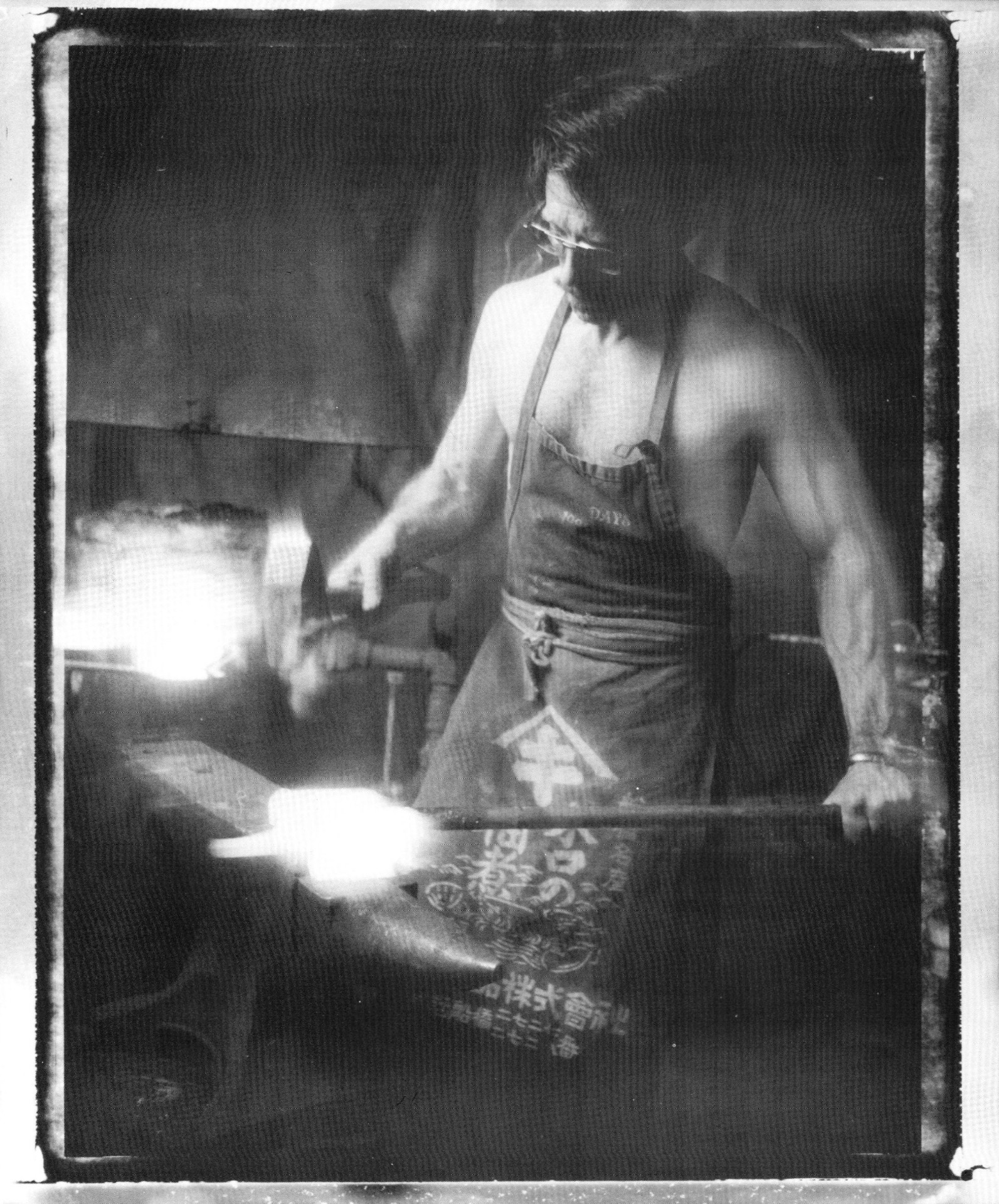

Taken as a test case, then, the art of Phillip Baldwin suggests how these approaches can be successfully combined. The 39 year old knife maker and iron sculptor lives near Seattle and is an active member of the long-respected Pacific Northwest craft community. A Puget Sound area resident since 1983, Baldwin has conducted numerous workshops around the nation at leading craft schools: Penland, Oregon School of Arts and Crafts, Arrowmont School of Crafts, Alfred University and at prominent national and regional conferences: ABANA, SNAG, New England Blademakers Guild, and the Northwest Blacksmith Association.

As a result of his participation in a two-year research project on the Japanese precious metal, Pattern process, mokumé-gane, at his graduate school, Southern Illinois University - Carbondale, Baldwin is known as an authority on the topic, as well as recognized as a producer of the exotic laminated metals for other artists through his company, Shining Wave Metals, founded in 1983 in Springfield, Missouri, where he was living at the time.

Given that extensive technical background, what does Baldwin's art look like - and mean? For one thing, his work takes on an extraordinary range of appearances. An early wrought-iron sculpture, Interrupted Helix, 1976 is an arduously arched series of bars which recall fellow New York sculptor David Smiths work of the mid-1940s. Reared in Northport, Long Island, Baldwin benefited from his mother, Nancy Baldwin, who is a professional potter, and from frequent trips to Manhattan museums and galleries.

The highly abstracted Interrupted Helix suggests Baldwin's modernist phase came early, along with Screen, 1979, an eight-foot-high mild steel construction which combines circular forms and curves, and the smaller Asparagus Grille, 1979, which bends vegetal forms, creating a rudimentary horizontal grid. A self-taught blacksmith, Baldwin also ventured briefly into jewelry or body ornament with his 1976 Wedding Crown, a startlingly beautiful silver tiara with branch and leaf shapes.

It was a 1976 American Craft Museum exhibition curated by Jim Wallace, Solid Wrought, however, which piqued Baldwin's interest in other metals. After initial inquiries, an invitation to attend S.l.U. soon followed. Once there, Baldwin recalls, he stopped making sculpture altogether because "formalistic exercises were not interesting," and he shifted to architectural metalwork for a while "because of a greater need in society" and made his first mokumé-gane piece, a small lidded container, in 1977. A few jewelry pieces resulted from these first Japanese experiments but, more importantly, functional tableware and a carving set with ivory handles were made at this time. The path to knifemaking was assured and apparent.

Coming to the Pacific Northwest in 1979, fresh out of graduate school, Baldwin first worked in Portland as a resident craftsperson at Oregon School of Arts and Crafts. Besides an umbrella rack, architectural hardware, and site-specific pieces such as an exterior balustrade, Baldwin concentrated more and more on blades. Firmly involved in knife making by 1984, when he joined the Knifemakers Guild, Baldwin quickly became dissatisfied with his successful commercial knives, the Field line of steak knives, ham slicers, and skinners and daggers for hunters. Gradually, he combined a growing desire for imagery with his substantial ability to create exotic layered metals.

Baldwin's "early maturity" phase began with a sword Blade Breaber, 1980, using outlined spheres as ferrule and handle base. A folding knife of 1984 used shibuichi, inlaid gold, and silver and an ivory handle. As the forms became more complicated within the rigid functional requirements, so the materials became more lush, regal, and mysterious.

Spear, 1981 and American Reply, 1985 are doggedly aggressive in content and form, suggestive of the intertwining lines of Celtic illuminated manuscripts or medieval English wrought iron. An axe with blades pointing in opposite directions, Going and Coming 1981, is especially barbaric and vicious-looking. It is as if, by evoking the cruder history of the tradition, Baldwin was carrying on a dialogue with his anonymous predecessors. This would not last.

By the late 1980s, Baldwin entered his current "decadent" or "palaceware" period. Richly ornate, sleek and intimidating his art since 1988 makes clear why the artist prefers the appellation "aesthetic worker" instead of craftsman. These works are a belated (120 years late) addition to the American Aesthetic Movement, (1860-1875) in the decorative arts. Whether gold, titanium, mokumé-gane, opals, or woods like ebony and rosewood, the materials take on a deeply symbolic character of their own, invoking both ritual ceremonies of an imaginary world, or fetish-points for the private fantasies of his new patrons from Italy, Japan, and the United States.

In a way, the artist has come full circle from Interrupted Helix. Having begun with functionless sculptures, later forsaken as "formalistic exercises", Baldwin now makes swords and knives so elaborate and beautiful, they discourage use - and hence, become sculpture by default.

Betrayal of function? Distortion of art? No, Baldwin seems to be having it both ways. Material involvement and presence of process are so blatantly evident that they go beyond function into dazzling virtuosity. At the same time, the sheer exquisiteness of workmanship is always tied to use through its form, thus elevating its appreciation to a symbolic contemplation of the blade.

The collaborations with sheath and handle maker Jim Kelso of Worcester, Vermont, confirm the indeterminate historical allusions to prior decorative arts styles: Aesthetic Movement, Art Nouveau, Japanese Edo, or Momoyama periods. Always evocative and never specifically allusive, joint efforts such as Autumn Dagger, 1990 and Magic, 1992 summon up worlds beyond the recognizable heritages which may have influenced their making.

This creation of an imaginary universe is what distinguishes art from craft to finally arrive at that thorny but unavoidable issue. Assertion of aesthetic status, alone, can never guarantee such conferral. It is the combination of masterful making, oblique reference points in history, and the infusion of personal visions into the object, which lift the work into the realm where the best of any medium finally arrives.

As his skills grew and flowered, and his individuality of vision matured, and these qualities became successfully transferred into his swords, Phillip Baldwin became an artist. He stepped onto the bridge between art and craft, a bridge undergirded by the iron of work but decorated with the precious metals of the imagination.

Matthew Kangas, Seattle art critic and curator, contributes to Art in America, Sculpture, GLASS, American Ceramics and other magazines. He has also written about Albert Paley, David Smith, Richard Serra, Robert Maki and other metal artists.

You assume all responsibility and risk for the use of the safety resources available on or through this web page. The International Gem Society LLC does not assume any liability for the materials, information and opinions provided on, or available through, this web page. No advice or information provided by this website shall create any warranty. Reliance on such advice, information or the content of this web page is solely at your own risk, including without limitation any safety guidelines, resources or precautions, or any other information related to safety that may be available on or through this web page. The International Gem Society LLC disclaims any liability for injury, death or damages resulting from the use thereof.

The All-In-One Jewelry Making Solution At Your Fingertips

When you join the Ganoksin community, you get the tools you need to take your work to the next level.

Trusted Jewelry Making Information & Techniques

Sign up to receive the latest articles, techniques, and inspirations with our free newsletter.