Metalsmith ’94 Fall: Exhibition Reviews

27 Minute Read

This article showcases various exhibitions in the form of collected exhibition reviews published in the 1994 Fall issue of the Metalsmith Magazine. This features Laura Marth, Bruce Metcalf, Laurie Hall, and more!

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

Metals Invitational '94

Emily Davis Gallery, University of Akron

Akron, Ohio

April 4 - 23, 1994

by Kathleen Browne

Sculpture predominated (by 50%) in Metals Invitational '94 curated by Christina DePaul. And as with any large group show the content of the work was wide ranging. Personal narrative, political and cultural critique, and more traditional, abstracted, and symbolic forms were all well represented.

Personal narratives in the work of two artists in the exhibition offered an interesting comparison. Gretchen Goss and Linda Threadgill both share an interest in commemorating and recording personal history. Gretchen Goss's Fading Dreams of Relaxation and Lake Huron #2 are both rectangular enameled wall pieces. Fading Dreams… has a central niche housing an abstracted boat form while Lake Huron… has a shelf protruding off the surface that supports a small rock. Marks made on a yellow field allude to writing, perhaps a faded journal entry. For Goss color seems to function as a mnemonic device; the colors associated with an event allow the memory of that event to be brought to mind. This work is subtle yet provocative.

Linda Threadgills moving piece Say, Good-bye is a rectangular wall piece with three small niches in a row toward the top of the composition, each containing a different quantity of tiny vessels. The center is a larger niche framed by photo-etched images of travel that contains a shape of an urn, cut in the negative. The piece speaks eloquently of loss, longing and transformation.

Leslie Leupp's recent series, Queer Objects, is some of his most compelling and most political work to date. The title Queer Objects is dually interpreted to mean odd, strange, etc. while referencing a slang word for homosexuality. Aside from the obvious play on words, Relic of the True Cause immediately brings to mind the innocuous ball-and-cup toy from childhood but in this version the ball is chained to another ball that already resides in the cup. The handle is fabricated from steel wire to create a cage for a ruler. This 'odd' object is part toy, part puzzle, part weapon, but most importantly a subtle discourse on gay sexuality.

Jewelry, approximately 30% of the exhibition was some of the strongest and weakest work in the exhibition.

A biting critique of the relationship of jewelry to affluence and luxury can be seen in two pieces from the Luxury Series by Myra Mimlitsch Gray. Both rings, the first, Game Piece, uses a lens to focus attention on the exploitation of the diamond industry as depicted by an embossed map of Africa (under the lens) as a game board with soldered gold rings at the location of nine gold and diamond mine sites. The object of the game is to shake nine "diamonds" (cubic zirconia) into the gold rings. This wonderfully sardonic ring evokes images of trophy wives gathered around to admire this 'fabulous conversation piece'. The second ring, Pave Pacifier, is in the form of a highly polished sterling silver pacifier with a burst of perfectly set pave "diamonds" (cubic zirconia) on the tip of the nipple. This is, of course, ready made for the budding capitalist ready to experience the eroticism of acquisition in a very tangible way. The irony of this work is that it so successfully and simultaneously exudes and critiques luxury.

Pat Flynn's, Rings, Brooch and Bracelet and his work in general is highly charged emotionally and difficult for me to intellectualize. The juxtaposition of unlikely materials and the balance of perfection and imperfection make this work particularly resonant.

Susan Kingsley's seductive yet menacing floral brooches are tamed due to their placement on black plexiglass plaque/supports. They really need to be seen in relationship to the body (perhaps displayed on a mannequin?) to achieve their full impact.

Three miniature narrative brooches by Susan Hamlet, Transitive Days, Ballad of the Heart and The Elusive Mission, employ an interesting array of symbols but seem too stiff and emotionally neutral in light of their loaded titles.

Ann Lalik's series of goddess brooches Hera, Artemis, Demeter and Aphrodite certainly doesn't lend anything new to territory already heavily mined by Carolyn Morris Bach and others and the stylistic similarities to Bach's work are somewhat problematic.

Considering the resurgence in hollowware in the last few years the representation of such in this exhibition seem somewhat timid. At the two extremes are Robin Quigley's pair of vases which appear static and leaden and Claire Sanford's Striped Vessel, and Green and Brown Pitchers, which appear animated and portray a peculiar individualism.

The works of Joe Wood and Kate Wagle are noteworthy although they defy categorization. Suite, Virtu: Harmony; Logic; and Deceit by Joe Wood all take the form of finely crafted display boxes (about the size and shape of cigar boxes) that each contain an object created by intersecting linear elements that form a three-dimensional configuration. Each piece is then labeled with its title on an ornately etched plaque embellished with a Tudor rose. These enigmatic displays suggest a 19th century gentleman/philosopher's attempt to reduce three loaded words to their absolute mathematical essence. The attention to detail gives it an air of authenticity while the overt sexual overtones of the configurations give the work a contemporary edge.

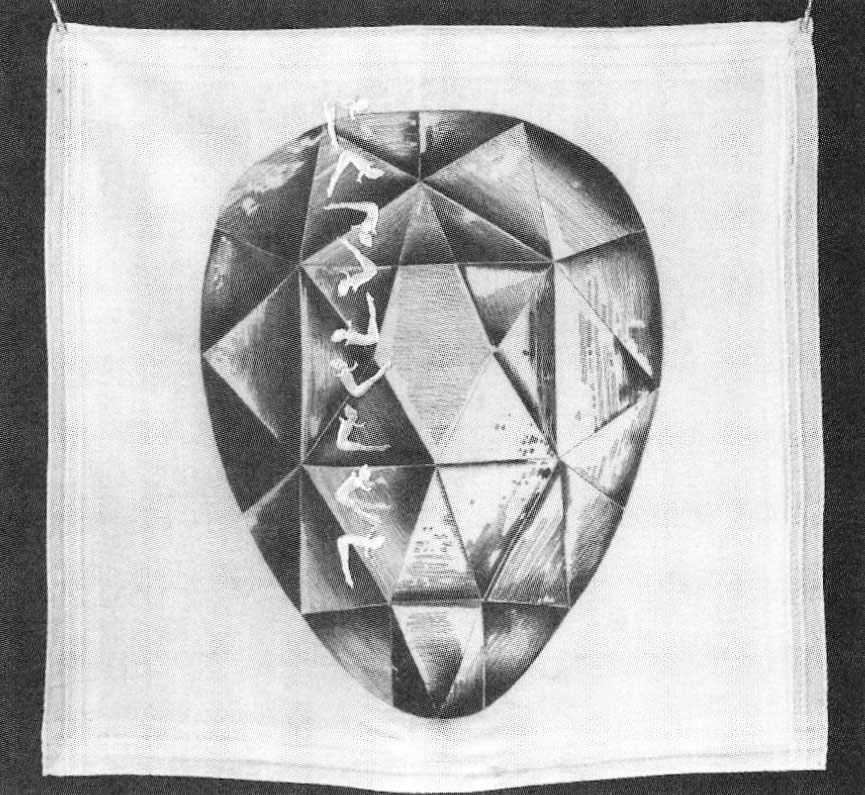

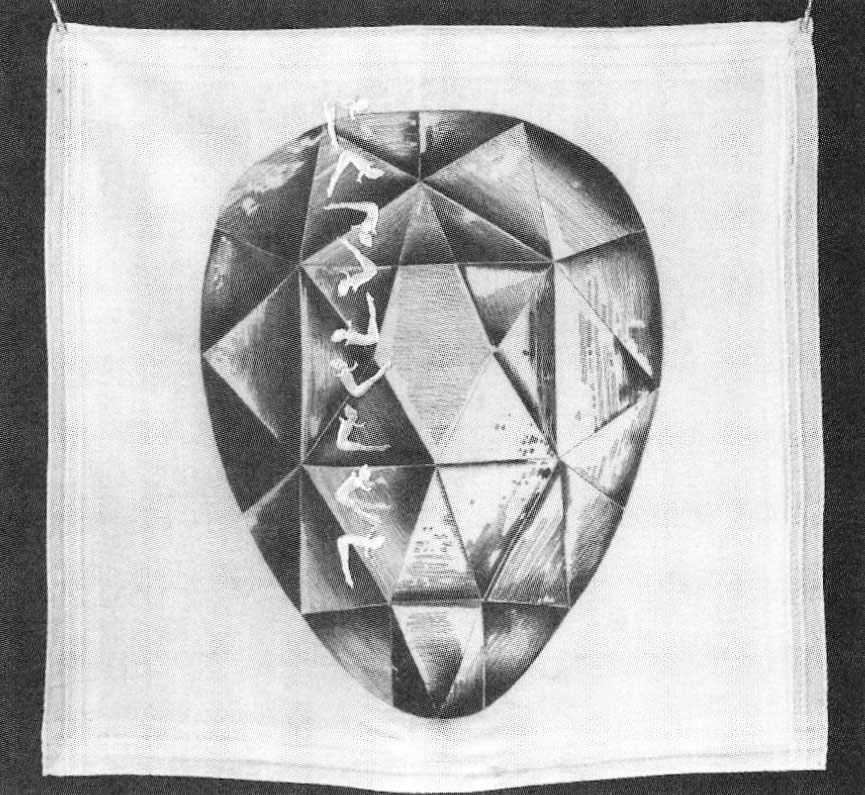

Kate Wagle's Vanitas series consist of four simple, white, cotton men's handkerchiefs that are pinned to the wall. On each handkerchief is a graphite drawing, and sewn on the surface of the drawing are embossed images in the form of tiny silver milagros. These works juxtapose the ideal and the mundane in an attempt to examine who we are in relationship to our hopes and dreams. In Vanitas: Stone and Divers, a perfectly faceted stone is rendered on a simple handkerchief while cascading down the side of the image are repeated milagros (representing everyday miracles) in the image of a diver performing the perfect dive. All of these works speak to the transitory nature of our existence and to the sustenance of small miracles. The most engaging of the four pieces is Vanitas: Hand and Rings where an x-ray image of a hand with wedding ring is rendered on the handkerchief. A grid superimposed over the image is only indicated by small gathers at the intersection of the grid lines. These intersections are punctuated by tiny jump rings. This piece reminds viewers of the indelibility of our relationships.

Other artists included in the exhibition were Boris Bally, Harriete Estel Berman, Jonathan Bonner, Stuart M. Buehler, Thelma Coles, Charles Crowley, Mary Douglas, Susan Ewing, Carol Kumata, Richard Mawdsley, Bruce Metcalf, Tom Muir, Tod Noe, Kiff Slemmons, and Didi Suydam. A black-and-white catalog is available.

Kathleen Browne is a metalsmith, writer, and teacher of metalsmithing at Kent State University, Kent, Ohio.

Laura Marth: In Excess - Narrative, Functional and Wearable Metal

The Joanne Rapp Gallery, The Hand and the Spirit

Scottsdale, Arizona

February 1 - 26, 1994

by Heather Sealy Lineberry

Like many contemporary metalworkers, Laura Marth has her own solution to the craft versus art dilemma that has pervaded and plagued American craft over the last forty years. Marth denies the pigeonhole mentality of the debate and instead uses traditional vessel and jewelry forms to tackle complex emotions and experiences. Her fanciful yet functional objects in new-car colors make a bold statement, in spite of image/object saturation and the frantic daily pace most of us cultivate. The recent exhibition "In Excess" featured eighteen anodized aluminum perfume bottles, pepper mills, earrings, brushes, and brooches that convey autobiographical narratives. Yet they function, and, as with much of the best contemporary craft, force the user and viewer to reassess the objects of daily life, their selection, use, and implied meanings.

As Marth writes in her statement, the title of the exhibition refers not to an excess of technique or of decoration but to an excess of emotion. Marth's perfume bottles and pepper mills, in particular, use vibrant colors and funky forms to convey the heat of passion or the intense grief of loss. It is not difficult to discern that Smoldering Red Mattress expresses the former. The body of the perfume bottle is a brilliant, shiny red and appears quilted, resting precariously on three burnt matches. Flames burst from the seams of the quilt and a spring - as in a 'sprung mattress' - forms the lid of the bottle, with a burnt match acting as stopper. Reality Strikes through deflated memories of the past records the loss of parents and the resulting loss of future moments and memories. The pearl-hued bottle appears wrinkled and flaccid, and is described by the artist as a deflated sack of memories. A small hand reaches from the lid of the bottle in the universal gesture of a child seeking a parent's reassuring touch. Using these bottles continues the narratives' as you grasp the child's hand and dab on some perfume, stimulating memories and enhancing sex appeal.

Marth utilizes the properties of her materials to expand the content and carry hidden messages for the user. All of the works are initially lathe turned and then band sawed and carved to achieve desired shapes and textures. The most successful pieces, such as Smoldering Red Mattress and Sweet Kisses in the Moonlight, use vibrant, over-the-top colors and sensual forms based on fruits and vegetables. These forms are deceptive to the eye - what appears soft and pillowy is actually hard and heavy. Sweet Dreams has a dimpled silver stem and pink cloud top which feel solid in the hands when grinding pepper.

Many of the perfume bottles rest their considerable weight and size on three insubstantial legs, a precarious balance corresponding with the content of the works but threatening their function. She got over it and Unsuspecting innocence, two of the darker pieces in the show, are the most dangerously balanced. The former bottle combines a bleeding pear as the body, a sinister black hand as the lid and three claw like legs. The piece is concerned with death and grief, and our inability to come to terms with either state. Unsuspecting innocence tells the story of a child's death and has the disturbing combination of pacifier, gray pear and eating utensil legs that seem to be attacking.

Despite balance problems, Marth successfully transcends the craft versus art debate, creating works that fall between the categories. She opts for traditional forms but freely alters them with narrative content. In recent works Marth leans towards feminist subject matter, but it is a new feminism that is concerned with the multiple roles women are required to play today. Marth's willingness to confront a range of experiences from sexuality to humor to grief leaves plenty of room for exploration and a lot to watch lot in the future.

Heather Sealy Lineberry is a curator at the Arizona State University Art Museum, Tempe.

Bruce Metcalf "Small Redemptions"

Susan Cummins Gallery

Mill Valley, California

January 31 - February 26, 1994

by Bruno Fazzolari

Bruce Metcalf does a lot of talking these days, which is certainly to our benefit as his ideas do their part to shake things up bit. However, problems arise in trying to separate the artist from the theorist: when encountering Metcalf's work, it is hard not to recall his most recent manifesto and compare his output with his goals.

His recent show attempts to explore what he calls the "moral possibilities of craft." Pay attention here, Metcalf is not lining himself up with the multi-cultural movement. This show is neither about activism, nor political identity, instead it is about precisely what he says it's about: morality (or as he puts it: "those shmaltzy (sic) virtues that nobody mentions anymore, like empathy and charity and pity.")

The works in this show attempt to illustrate such virtues as feeding the hungry, housing the homeless, and catching the fallen. Metcalf deals with these issues on a very literal, narrative level. His figures (mostly brooches) are blobby, organic creatures, with big heads and small extremities. They are presented on architectural stands which allude, rather arbitrarily, to various historical architectures (a roman arch, a Greek alcove, a proscenium stage).

Jewelry is a tricky place for moral and social commentary. As a cultural object, with its long history as both spiritual tool and marker of social status, its tradition is more than capable of supporting such investigations. However, its formal concerns can make the use of narrative figuration somewhat awkward.

Metcalf's brooches are unwieldy; at once too simplified and too complex to achieve their ends. It seems as though he is straddling the fence between jewelry and figurative sculpture, and is consequently unable to deal decisively with either. It both cases, he doesn't engage the media or the tradition intensely enough to avoid banalities. Why Metcalf feels compelled to uphold the pretense of wearability in these pieces is baffling. The pins attached to these figurines are vestigial reminders that they are indeed jewelry, but it is an afterthought, many have clearly been designed with their stands in mind and are as linked to them as actors are to a stage. There may be a metaphor here ("All the world's a stage…"), but it is a trite and hackneyed one.

In its illustration of good deeds, the show develops more than a few Dickensian overtones and adopts the same patronizing Victorian attitudes towards the poor and unfortunate (in these scenarios it is always the big ones who help the little ones) which made that writer's benevolent attitudes so insufferable. It is curious (even daring) to see such values presented without the usual post-modern tongue-in-cheek. If Metcalf would handle these ideas with something like savvy eloquence and charm they might actually achieve their mark, unfortunately, the work has the sort of brassy sentimentality characteristic of Hummel figurines.

Possibly the most distressing aspect of this work is the cultural context of the jewelry itself and the conflicts of interest which can arise when producing luxury items with the poor in mind. Metcalf writes that he doesn't expect his jewelry to change society instead it is directed towards providing a modicum of healing in the world, "they stand as statements and gestures" for the artist and wearer. But the problem is that they can only serve to heal the classes who can afford to buy fine jewelry the very classes who are hurting the least. Like fur-coated ladies stepping-over the homeless en route to a benefit, the would-be owners of this jewelry have a heavy load of guilt to shoulder. One wonders, when these brooches are taken from their stands and given a chinchilla stage, will their owners be aware of the irony, or will they be too busy measuring the social register that records their "good" intentions?

Bruno Fazzolari is a painter and writer who lives in the San Francisco Bay area of California.

Laurie Hall

MIA Gallery

Seattle, Washington

February 3 - 27, 1994

by Matthew Kangas

In her Fall 1986 Metalsmith cover story on Laurie Hall, "A Primitive Contemporary," LaMar Harrington bent over backwards to do justice to this unusual and original Northwest jeweler. No less than 17 artists were mentioned in relation to Hall and, in extensive quotations from the 50-year-old West Seattle artist, Calder, Matisse, Picasso, and Magritte were invoked besides, of course, her University of Washington graduate school instructor Ramona Solberg and her New York mentor Robert Lee Morris. The work illustrated was complicated and ambitious, witty and unexpected.

Hall's recent MIA Gallery show was a major let-down in a number of ways. Definitely not up to the standards set in the Harrington article ("nonsensical…poetic…almost ritualistic"), Hall also seems to have subverted her own self-criticism, as when she told Harrington, "a piece of art without mystery becomes craft and [Hall] recognizes any such shortcomings in her own work immediately."

That may have been true eight years ago but today, not only is the mystery missing, but the work even seems to fail as craft. Loosely carved, with what can only be described as nonchalance bordering on indifference, the dozen pins, brooches, and necklaces lack any mystery at all and seem rushed in conception, arbitrary in construction.

What happened? The promise and enthusiasm Harrington praised seem not to have been fulfilled but rather deflated or dropped. Instead, an informality of presentation tied to a prevalent, late 1980s reaction against super-technique has taken her too far in the other direction. A three-part necklace, Pinned, 1993-94, is a major failure, as it appears clunky and cobbled-together. Crudely carved sections of wood stand in as biceps and forearm, or leg and calf parts as the two outer modules and an inner handsaw shape connects the two limbs. Since each section may be worn separately as a brooch, it's worth considering them independently but they simply become one-line jokes, something all too common to Pacific Northwest crafts in general.

Another one-liner I Wood If I Could, 1993, literalized the sentence into a word-puzzle or rebus necklace including a big bronze "I" for one side of the necklace. Here Hall's collapse of faith in the power of the image in favor of language is painfully clear but, apart from the lame pun, the meaning seems unclear.

Exactly what is, even vaguely, being communicated in these works is also not evident. Dream Overhaul, 1993-94, at least has red blood dripping from a handsaw blade but Red Handed, 1993-94, is just a repetition of the hinged-limb idea with a cartoonish red hand. Dummy, 1994, at least is an entire body - cut in half lengthwise - with an aluminum torso so that there is some figurative-sculptural potential. Simplistic rather than simple fabricating solutions seem to be the order of the day as if the entire body of work were rushed - or shown before being fully finished.

Two metal pieces redeem this endeavor somewhat though their imagery seems woefully derivative of "Calder, Matisse, Picasso…" No Strings Attached, 1993-94, is half-stringed instrument, hall-face-in-profile. There are mock wood-grain lines on the violin surface. My Spanish Guitar…La, La, 1993-94, uses the clever convention of playing hands and arms as the outer sections of the necklace. Especially in the mixed-media wood-grain pieces, Hall seems more "primitive" than "contemporary." With such extensive educational and postgraduate training, though, this "primitive" cannot fall back on folk-artist status, unlike many of the artists represented by the MIA Gallery.

There once might have been a uniting artistic vision that could have held this show together. Wood has tremendous social and political overtones in this part of the country - endangered species, threatened jobs and way of life, ecological crises, cliché recreational pursuits - yet Hall has sidestepped alluding to any such issues. Woodpile, 1994, is a "pile" of tiny coin-shape wooden cross-sections next to a sterling silver wire. Everyman 1993-94, is a sterling silver double-handled logging saw with a quotation from Thoreau but such a blatant literary recourse is superfluous.

Wearability and scale problems aside, Laurie Hall needs to seriously reconsider a number of things: wit over seriousness; loose over tight; and puns over symbols. Fallen far below her own standards of technique and meaning of a decade ago, she now must approach sculptural jewelry anew rather than reiterate and recapitulate, rush and recycle.

Matthew Kangas, a Seattle art critic and curator, is a national correspondent for Sculpture, and contributes frequently to Art in America, American Ceramics, and GLASS.

Metal Vessels: A forum for interpretation of vessel from involving explorations of function and material

Iowa State University

Gallery 181

Ames, Iowa

November 1 - December 2, 1993

by Jean Sampel

This collection of work illustrates a great cross section of North American hollowware. There is the beautiful vessel, the useful vessel, the vessel form as sculpture, the experimental form and the metal form disguised. Almost every piece is illuminated by an accompanying artist's statement and it is noteworthy how cerebral this work is.

Perhaps Joe Muench responded most intellectually to Professor Chuck Evans theme, with his amazing sculpture, Vessel. According to Muench, it "deals with the transitory, stopped motion, stopped time. The silver 'flag' has been transformed for a split second into a vessel by the forces exerted upon it, by the banded sphere which has been hurled towards it, striking it from some unknown space, creating for this frozen section of time - a vessel." Muench's impeccable craftsmanship became his means of dimensionally describing his mental examination.

Most of the more functional hollowware forms evolved beyond traditional form in some way. Charles Crowley's three handled chalice and his sterling teapot with a graceful tubular aluminum handle, painted with black and white stripes, come to mind. Michael Jerry's pewter Pitcher This possesses the whimsy of an animated dancing Disney character. Susan Ewing's Inner Circle, Teapot I is rotated on a large spiral coil as it is used, demanding real involvement of the user. Alexandra Mikesell's elegant sterling goblet holds a surprise with its rusting steel core teasing the viewer through its pedestal. Her statement: "…this work reflects concern for preservation of the past, integrated with the present, in anticipation of the future" is a thought-provoking basis for this lovely piece. And the question, "Which came first, the piece or the philosophy?" is simply rhetorical since reflection on the personal symbolism that emerges may surprise even the maker.

The tall sculptural brass, bronze and aluminum stand that Tom Muir gave his sterling bowl in Untitled Hollowware was likely intended to give the bowl added credibility. Might the bowl have been appreciated/accepted as the finely crafted, well-proportioned traditional form it is? Probably not in his circles. Is it more or less a fine piece because of the added base? Will anyone dare present a pure form as a pure form ever again? Marcus Amshoff's two die-formed copper vases are practically that: simple, captivating forms that reveal their die-formed manner of origin and then call to the viewer with their electric blue patina. They are fine pieces where simple form is the statement. Dale Wedig, guest lecturer for the accompanying symposium, exhibited two symmetrical raised vessels. One, Great Pumpkin Vessel an awesome 30 x 16″, is intersected with constructed channels, painted in colors that contrast with the soft orange, body color. It is evenly patterned by cutting through the paint revealing the copper body. This timeless and elemental form certainly belies the technical virtuosity of its maker. That it could be the work of the same mind and hand as the series of three cast aluminum sculptures also shown by Wedig is amazing! These identical crude forms with their differing body textures and appendages, all painted, seem to be disguised as ceramics, which they just as well could have been.

In the task of reviewing, it was interesting to try to determine where each artists' preoccupation lay: in expert manipulation of the physical materials or in the academic exploration of an idea, a philosophy, another medium or culture? Boris Bally's Lonely Poppy Urn, a raised aluminum stop sign complete with some of the red letters, an example of his "ongoing experiments with discarded materials" illustrates the former. As for the latter, Randy Long's two pieces "represent my exploration of architectural themes within the form of the vessel… a dimensionalized painting inspired by the work of Gothic painter, Pietro Lorenzetti." Long's objectives were carefully preconceived and challenged hand work. This whole show illustrates Sidney White's premise that art is a way of life, and the work of art resulting from that life-process is a product of emotional, sensual and intellectual forces, becoming a record of that life; varied works marking a place in each unique individual's evolution.

Jean Sampel is a metalsmith who works in Des Moines, Iowa.

Marilyn and Jack da Silva: Metalsmiths

San Francisco Craft & Folk Art Museum

Fort Mason Center, San Francisco, California

March 19 - May 22, 1994

by Marvin A. Schenck

Some artist couples' artwork can grow similar in content or design, but this is not the case with the metalsmiths Marilyn and Jack da Silva. Jack's work is a continuum of contained functional form distilled from the historic traditions of metalsmithing. Marilyn's work is a ride through her dreams using the most seemingly unconventional techniques. These differences between their work heightens the experience of the show. Each serves as a backdrop to view the other.

The show represents sculpture and functional ware from the mid 1980s to the present, each artist has some ten pieces on display. Though the installation, for the most part, separates the works of each artist, comparison is easy due to the intimate mezzanine gallery setting.

Jack da Silva mentions in his artist's statement that his ancestry is of a family of artisans. "Learning to work with my hands was a natural part of growing up. Everyone, it seemed could rearrange material…" Jack has taken this passed down talent and added an interest in ancient and traditional metalworking methods. His immense abilities in traditional raising techniques using copper and silver are truly inspiring. He adds to this skill a graceful simplification of design. Two recent sterling silver works, Chalice, 1992, and Pitcher 1993, are premier examples. The two have such an airiness in their creation that they look light to the touch. They bring to mind the legacy of the Bauhaus and its traditions of form following function and a refined aesthetic of clean related design elements.

Another stylistic direction Jack has explored is represented by a low copper bowl from 1985. It has a free form rounded shape rather than the more symmetrical ones of Pitcher and Chalice already discussed. There is also a related Pitcher from 1993 in sterling silver that conveys a certain massive free flowing form. The difference between these two styles is that of fine twentieth century design through geometric elegance and an earthy natural form born from centuries of design for simple use.

Marilyn da Silva's creations are windows into her life. The Pillow Box series from the mid 1980s look as if they are made of lacquered wood instead of metal and paint. They tell of the precious time spent in the Far East. In the Above and Beyond series she takes elements of Eastern and Western design and lets them do battle as she creates wonderful 24 x 24 x 24″ sculptures out of copper, brass, bronze, steel, gesso, colored pencils, and paint. These works could all be blown up in scale to create captivating major outdoor sculptures. They illustrate a voyage Marilyn has taken to find her style and materials (Above and Beyond V even looks like a boat at sea). They also foretell the more narrative approach to come.

With her latest works Marilyn has arrived home. A new personal narrative style has emerged out of the autobiographic saga of Jack and Marilyn's house. The house was a personal urban renewal project that succeeded in becoming their dream home, only to be threatened by neighborhood crime and finally succumbing to a fire. The Put Out the Fire I, II, and III candle snuffers from 1993 represent first the dream house, then a house on fire, and finally a castle tower to protect them in the future. In The Lights are on But Nobody's Home from 1994 a wonderfully crafted cartoon teapot comments on leaving the lights on to fool the burglars. Using pewter and copper for the main structure (signifying home and hearth) in combination with steel tacks mounted on the roof (for protection) and a fragile purplish glass representing chimney smoke (and security), she offers subliminal messages through the wide assortment of materials. I find these new works to be poetry in metal. The image is the story, the design is the rhyme, the materials the nuance, and the universality of the personal experience the enlightenment.

Marvin A. Schenck is a curator and artist living in Oakland, California. He was co-curator along with Colleen Schenck, his metalsmith wife, of the "California Metal" exhibition last year at the Hearst Art Gallery at Saint Mary's College of California.

Tone Vigeland

Helen Drutt Gallery

Philadelphia, PA

April 22 - May 20, 1994

by Jan Yager

Norwegian jeweler Tone Vigeland's solo exhibition at Philadelphia's Helen Drutt Gallery didn't dazzle me with new techniques, costly materials, or self-conscious narrative. Vigeland instead deftly turned me towards transcendent beauty via simple processes, and pure concepts - exquisitely executed. She potently demonstrated the cumulative power o[small tasks done repeatedly, done methodically, done obsessively; worked and reworked, until they achieve absolute perfection.

Her exhibition consists of 20 works: seven neckpieces, six arm bracelets, five finger rings, and two skullcaps. In all Vigeland uses only thin gauge sterling silver sheet and wire, and presumably only a few simple tools to fabricate elegant cellular structures in metal. Each piece is an elaborate permutation of linkage systems she has devoted decades to exploring. Vigeland has developed a well-deserved international reputation for this work.

The Helen Drutt Gallery is also recognized internationally, and is exemplary in its presentation of fine studio jewelry. Large wall mounted display cases span three entire sides of the room devoted to jewelry; nothing is permitted to distract your focus from the show.

The artist installed the show. She gave careful consideration to the placement and arrangement of each individual piece, always with the composition of the whole in mind. To simulate how it would be seen on the body, her bracelets were displayed on wrist-size cylinders of gray paper, and rings stood on finger-size cylinders. Two necklaces were draped over horizontal shoulder-like cylinders, others draped vertically over tall neck size cylinders of paper. The muted gray tones of the oxidized silver jewelry and similarly muted background resulted in a pure, uncluttered, and straightforward presentation.

One wide collar of dark tactile silver was designed to drape sensuously over the shoulders and dips midway down the wearer's front and back. It was a dense mass of over one thousand meticulously crafted small rice-like forms. Each individual unit was textured to take on the surface appearance of rusted steel, and then loosely joined to a flexible mesh base; organized chaos resembling the beauty of a logjam in a river.

Another necklace was composed of a subtle graduated progression of delicate, slightly domed discs. This thick heavy strand of silver looked much like a long flexible pine cone cascading nearly to the waist of the wearer before looping back up to the neck.

The most significant and memorable quality of Vigeland's jewelry does not reveal itself from static display. Only when handled, and worn, does the work genuinely come alive. Bracelets worn 4″ or 5″ wide on the arm, will when removed, stand up on their own. Yet when laid on their sides, they suddenly slump, and with little prompting stretch a limp, floppy 13″ or more. Formfitting skullcaps, instantly deflate, when removed from the head; collapsing into puddles of silver. Many of the pieces are so flexible, so liquid, they need to be patiently coaxed on, and shimmied carefully into place. Ultimately requiring the assistance of gravity and the natural weight of the silver.

Vigeland's work easily expands the limits of wearable contemporary jewelry. But more importantly, it introduces a new 'body consciousness' to the wearer. It is engineered to be smooth, soft, and flexible. It is intended to cling heavily, and embrace the body. It is meant to become a second skin. It is meant to become the wearer.

Tone Vigeland sets a standard of excellence for studio jewelry by bringing an uncommon focus and intensity to the process of creation. Her decades long pursuit reminds us of what can be attained when developed thoughtfully, patiently, incrementally: masterful works of the highest possible caliber.

Jan Yager is a studio jeweler who also writes and lectures on Jewelry. She lives in Philadelphia, PA.

You assume all responsibility and risk for the use of the safety resources available on or through this web page. The International Gem Society LLC does not assume any liability for the materials, information and opinions provided on, or available through, this web page. No advice or information provided by this website shall create any warranty. Reliance on such advice, information or the content of this web page is solely at your own risk, including without limitation any safety guidelines, resources or precautions, or any other information related to safety that may be available on or through this web page. The International Gem Society LLC disclaims any liability for injury, death or damages resulting from the use thereof.

Related Articles

Samuel Yellin, Metalworker

Metalsmith ’95 Winter: Exhibition Reviews

James Evans Jewelry & Small Objects

Something Special in NE Wisconsin

The All-In-One Jewelry Making Solution At Your Fingertips

When you join the Ganoksin community, you get the tools you need to take your work to the next level.

Trusted Jewelry Making Information & Techniques

Sign up to receive the latest articles, techniques, and inspirations with our free newsletter.