Metalsmith ’91 Summer: Exhibition Reviews

33 Minute Read

This article showcases various exhibitions in the form of collected exhibition reviews published in the 1991 Summer issue of the Metalsmith Magazine. This features Aaron Farber Gallery, James Meyer, Mel Wolski, and more!

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

The Haiku Show

Aaron Farber Gallery, New York City

January 18 - February 23, 1991

by Anne Crowley Tom

The theme of the show, haiku (the traditional Japanese, 17-syllable, three-line poem) was the idea of goldsmith Antonia Schwed, brought to fruition by curator Patricia Faber. Traditional haiku always alludes to nature and seasons, referenced through symbols, like frogs to summer and cherry blossoms to spring. Hiroko Sato Pijanowski illustrates her own haiku about a drifting cherry blossom on a frozen sea with a piece that has a textured, plexiglass table top with a removable brooch of fine silver, gilded gold and, shibuichi in the form of a cherry blossom.

But, while Hiroko's contemporary design in Japanese-influenced, Antonia Schwed's piece has a native American or pre-Columbian esthetic. Schwed responds specifically to the humorous poem of Issa, one of the four great masters of haiku:

You hear that fat frog

In the seat of honor, singing

Bass? …That's the boss.

Her sterling silver and vitreous-enamel necklace, striking and stylized, stays within the bounds of abstraction.

A more literal approach is taken by Chris Darway, who interprets a humorous event described by the last of the four great Japanese masters, Shiki:

Oh! I ate them all

And Oh! what a stomach ache…

Green stolen apples

Darway presents this scene in Oh! Green Apples - the raised design of a stomach with two green tourmaline apples on a square pin of 14k yellow and white gold, sterling silver and copper.

Larissa Rosenstock illustrates the work of the earliest of the four great masters of Haiku, Basho, in Bamboo Brooch. In Rosenstock's 18k yellow gold and diamond brooch with its calligraphic brushstrokes, there is the harmony and perfect tone of one who studies traditional art of many cultures.

Carrie Adell best reflects the Zen Buddhist roots of traditional Japanese haiku in her own poems and the jewelry through which she illustrates them:

The touchstone cools

The hand that warms it, and

Brings the mind to know the now.

The haiku and pieces work as well as they do because they are a product of her deeply integrated Zen philosophy. An artist who has lived by a river a good part other life, Adell has created a series of gold, silver and copper "pebbles," many set with diamonds and pearls and engraved with her own haiku, that have the energy of stones recently tumbled ashore. As modular work, the stones can be strung interchangeably on her neckrings, multipins, chains and earrings of gold, silver and stainless steel.

Haiku and jewelry is a brilliant theme that could not have come off without the unique sensitivity of the artists and likewise the support of the gallery. The profound simplicity of the display itself - sparingly placed dry flowers, carefully arranged stones and jewelry on bare branches rendered a haiku tranquility, an inspiration to go home and write haiku.

Anne Crowley Tom is a freelance writer based in Manhattan.

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

C. James Meyer

Susan Cummins Gallery, Mill Valley, CA

January 7 - February 2, 1991

by Roberta Floden

Although the jewelry of C. James Meyer may seem rather conventional at first glance, upon closer inspection his conservative attitude toward expensive materials and economical designs reveals itself to be an understated contemporary expression. As Meyer says, "For me to reject the history and traditions of jewelry would leave me in a void. Instead, I wish to define jewelry's traditions and redefine society's accepted notions of jewelry in the effort to push jewelry forward."

Meyer derives the unique character of his jewelry from techniques and designs based upon the properties of steel wire. In one pair of triangular earrings, for example, each earring consists of a length of rounded steel passing through the pierced ear and then bent sharply so that the wire can be placed through a horizontal gold tube that forms the base of the earring. Though structurally strong, these earrings appear delicate and feminine. And, like all of Meyer's jewelry, they are practically impossible to lose.

Meyer's necklaces take steel wire even further. In these pieces, the wire is bent curvilinearly, then slipped over the head and allowed to assume its ultimate shape as it encircles the neck. Again, the steel is held in place by one, sometimes two, gold tubes often embedded with diamonds.

These circles of wire are punctuated by pendants not only of semiprecious stones - rose quartz, garner, tourmaline and opal - but of highly polished marble and granite as well. They are frequently embedded in gold bezels. The subdued colors play against the opacity and transparency of the stones, as well as with the gold and diamond tubes.

The necklaces are engineered so that the rod-within-a-tube construction allows for a certain amount of movement: the wire can be manipulated by the wearer to change the necklace configuration for dramatic effect. Because of this, the wearer is challenged to somewhat alter the design to suit the occasion.

Meyer's brooches - large, oversized pins - emphasize elemental, geometric shapes. Again, steel is the primary element, carrying gold and silver circles, cones and triangles, and stones. When worn, the brooches come alive: you can't see the wire, only what the wire is connecting.

His rings, on the other hand, though basic, gain effect through the enrichment of surfaces with ornamental detail such as pink and white gold inlaid into high-carat yellow-gold. They too are concerned with geometry, based on the circle (fitting the finger) within a square, upon which a stone might be set under or over gold. In other words, a ring might look square, but it feels and fits round.

Restraint and lack of excess are Meyer's signature. If there are expressions of exuberance, they show themselves in the jewels, the rich patinas and the highly polished, technically sophisticated surfaces. Visual interest is garnered primarily through shifts of focus created by the tension of the moveable curved wires; through contrasting forms of cones, triangles, ovals and circles; through the exploitation of the innate qualities of the gray-toned steel; through the use of precious and semiprecious metals and stones, and the juxtaposition of the softness of marble and opals against the gleaming gold and diamonds; and through the variety of textures and reflections created by light playing on these elements.

Meyer's work breaches the staleness of conventions by its fluidity, its use of disparate materials and its intensely graceful, visually balanced designs. The hand of the craftsperson is always evident, and the history and function of jewelry are never denied. Instead, Meyer carries tradition forward with respect, illustrating a love for the craft and for its materials.

Roberta Floden is a Marin County, CA, artist and theater critic.

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

Mel Wolski: "My Big True North"

Kensington Silver Studio, Toronto, Ontario

November 30 - December 24, 1990

by John MacAdam

Using icons of everyday Canadian life, automobiles, houses and hockey, Mel Wolski reveals an intensely felt sensibility, encompassing both humor and satire. A collection of pins, exhibited within a converted television set, are fabricated in marriage of metals (silver, copper, brass). They feature a series of suburban landscapes car, house, and tree - with each element seen in profile, the archetype of suburban living; the pin, a badge of middle-class values. Unique among these is a brooch depicting an escapee from the nondescript, emerging with a fiendish intent to press the line between the predictable norm and his own turf.

A similar motif appears in a pair of remarkable cylindrical, stemmed drinking cups, documenting in marriage of metals, a round of drudges found toiling on the underside of the cup bases. Each cup is differentiated from the other by either an X or an O, featured in the surface design. Though one cup may be chosen consistently over the other by the viewer, one has chosen only one's own version of the same weary story.

Two major pieces, Hockey game 1 and 2 recreate Canada's national pastime in miniature, mechanical, working models, reminiscent of childhood tabletop-hockey games. More than a game, these metal sculptures compel the viewer to examine and choose roles as player-observers in the complex interrelationships that aggressive, defensive, competitive situations demand. The viewer is compelled to mentally "play the game" as a visually intense experience. Likewise Winger, a large wall plaque featuring a sliding hockey player, challenges the viewer to "put one past him."

Wolski has extended the utility of a silver honey pot, an intricate container for condoms and an open rectangular box in Something for Honey (Loue - distance/time), unifying each element to achieve a successful personal statement on the vagaries of long distance romance.

My Big True North represented a body of work consistently tart and assertive, establishing a direct and challengingly playful interaction with the viewer.

John MacAdam enjoys the privilege of being a collector of fine art.

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

J. Fred Woell Mixed Media Sculpture 1967 - 1990

Wheeler Seidel Gallery, New York City

November, 1990

by Jamie Bennett

Given the scope and the nature of this exhibition, it would be more appropriate in a museum than a gallery. The sculptural works spanning a quarter-of-a-century are crowded in the available space, undermining the individual spirit of many. One is also quickly frustrated in attempting to understand the sequential relationship of the works when none are given dates. What this exhibition does offer, however, is a unique opportunity to examine Woell's sculptural explorations, which are less celebrated than his jewelry from the mid-60s and 70s. These sculptural tableaux and constructions are divided into three phases: the earliest cast bronze and epoxy reliefs and sculptures dating from the mid-60s; a group of almost 40 miniature bronze-castings from the 70s; and mixed-media assemblages from the early 80s.

Although there are formal shifts in Woell's work, there remains at its heart a vision of his America with its ironies and misguided values. Much of Woell's world is set into compact works, and through his sardonic style and skeptical humor he examines its incongruities. Woell's persistence in exploring the darker side of the human condition is found early on - Things Go Better With Coke (1969), a crucifix, where an epoxy Christ rests on an inverted cross whose cross member is made up, in part, by two worn Coke cans. This is an enduring and powerful work whose message is none too subtle. Jesus Saves Everything, Part II (1967) suggests the degradation of public trust by our institutions.

Woell has used any number of maxims as titles. They play on the original meaning, further intensifying the sculpture's content. He paraphrases Shakespeare in Much To Do About Nothing (1985), offers platitudes and Americanisms - Cycle For Your Health (1973), Be Prepared (1974), Was The West Really Won (1983). He goes on with manipulated mottos, homily, and advertising slogans. These titling devices tend to reinforce the social commentary of Woell's thinking and exemplify what at times is his bitter anger. The work from the early 70s is perhaps the angriest, the majority of which relate to the Vietnam war and the declining American spirit. Consider these miniature tableau as allegorical portraits and references to glory. Woell uses the traditional means of glorifying war and the warrior, the bronze statue. He disrupts the sanctity of war as an occasion for glory as well as the statue as a glorifying and legitimatizing device. One could challenge or subjectify the role of the miniature in these works as either undermining the power of size or utilizing the power of scale. There is no question, however, that the ornamental and ordinary jewelry boxes incorporated into many of these pieces, as replacements of the statue's pedestal, add a poignant counterpoint and esthetic irony to the celebration of the war trophy. In works such as Goosed(7972), 10-4 (1974), Stop the War I Want To Get Married (1974), Cockfighters (1972), How the West Was Won (1975) and A Day In The Life Of Everyman (1975), we find at times grotesque constructs appearing in many incarnations. Where an arm should be, there is a M-16 rifle pointing from the shoulder; from the crotch of a soldier emerges a defiant arm with a clenched fist; from the neck of a seated figure, a newly wed couple sprouts. Woell's portrayal of everyman is not a flattering one. Works from this period are not all topical, exploring an expanded emotional range. Consistently, however, Woell is addressing his relationship to America. Just Another Day In The USA (1975), Down On The Farm The Chickens Ask For you (1975) and Requiem To A Lukewarm Lover (1982) offer various scenes of pathos and Woell's private protest.

Although the passion for social commentary persists into the 80s, there is an overriding mood that is far more self-reflective than angry. A group of works entitled Bach to Square One, which are all 8″ x 8″ wall panels, are not only of a more personal and biographical exploration, but also more formally exact and elegant. They appear to be archival objects and assemblages. Back to Square One has as much to do with the relationship of an artist to himself as that of art with society. Time Goes You Say? Ah No! Alas, Time Stays, We Go!, Nonesuch Person/The Male in Midlife, Art in America, Circa 1960s, Western Veneer and, Urban Landscape, all from 1983-81, seem to use slogans less as cries and more as inquiries. These small constructions represent a movement from a sculptural context to a pictorial format, yet they remain very physical, and one clearly gets a sense of Woell's poetic and political interest in materials and cast offs (many of these pieces deal with environmental issues) as resonant images. The best of these works are succinct messages, clear and articulately rendered. Those that tend to be introspective and sell-searching do not reach our as strongly and tend to be marred by sentimental pitfalls.

What one realizes from this show is Woell's ability to capture the moment in America and in the case of Back to Square One, his own moment to rekindle his relationship with art and being an artist.

Jamie Bennett is an enamelist and professor at SUNY, New Paltz, NY.

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

Reflections of the Past and Present Contemporary American Silver

The premier exhibition of the Society of American Silversmiths

The Society of Arts and Crafts, Boston, MA

September 6 - November 9, 1990

by Curtis K. LaFollette

It is perhaps fitting that America's newest metalworking organization - a trade association rather than nonprofit - The Society of American Silversmiths (S of AS) should deliver its premier exhibition through America's oldest arts and crafts showroom, The Society of Arts and Crafts in Boston. Catalog notes were prepared by Edward S. Cooke, Jr., associate curator of American Decorative Arts and Sculpture at the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston. The exhibition reflected almost the entire history of American silver, from reproductions of 18th-century ware by James Curtis of Williamsburg to geometric teapots by Susan Ewing. There was work by Rob Butler who is not college trained and by Fred Fenster who is. There was corporate executive paraphernalia by Harold Schremmer and table sculpture by Heikki Seppä. The list could go on and on. In fact this is a totally eclectic survey of the artisan membership of S of AS, including 60 pieces, produced by 29 of the society's 46 artisan members. This membership category is juried and artisan status is conferred by Jeffery Herman, Harold Schremmer and Michael Brophy. Only artisan members are included in society-sponsored exhibitions. Herman is also the founder of the organization and publisher of its brief but tasteful, quarterly Journal. There are 68 additional members in supporting and associate categories.

Jeffery Herman discovered his interest in silversmithing when, at 16 years old on a summer trip to Cape Cod, he met Neil Turkelsen in his studio/salesroom and was spellbound. He immediately took continuing education courses at Southern Massachusetts University, and worked his way through the Portland School of Art in Maine selling silver jewelry he had fabricated at home to earn a BFA degree. He studied with Tommy Thompson for two years and with Harold Schremmer. Since 1984 he has maintained his own business - a sole proprietorship primarily directed toward antique silver restoration and allied services.

The society does not take any position on esthetic issues. It is focused on craftsmanship and technical competence. S of AS is an umbrella organization equally dedicated to the promotion of its members and the recruitment of students to the profession. It is apparently, quoting Herman, "the only such organization exclusively for silversmithing." Services include trade discounts, advertising discounts, referrals, networking, exhibitions and the Quarterly. For students there are additional potential benefits, including advice on technical matters and personal presentation.

Herman is especially concerned that the median age of the society's artisan members is 51. He attributes this in part to design schools that have not adequately addressed the structural needs of scheduling for technically complex procedures. He prefers the European model where there is greater specialization. In most American design schools the training is watered down. You almost never see the finesse in handling hinged lids and other difficult techniques in contemporary American metal that was commonplace in the 19th century. In Europe, students can still specialize in boilerplate chasing, repoussé or engraving, whereas here, if specialities are taught at all, they are peripheral, complementing raising or forging, but not an end in themselves. Herman would also like to see more attention paid to other difficult skills, box making, for example, or vessel faceting. It would also be useful for students to have a greater exposure to early silver, both from the standpoint of restoration and just to observe how things were put together. The foundation of silversmithing in this view is technical virtuosity rather than intellectual analysis.

Curtis K. LaFollette is a professor of art at Rhode Island College in Providence.

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

Sculpture to Wear

Adair Margo Gallery

El Paso, TX

November 2, 1990 - January 18, 1991

by Frank C. Lewis

Seldom has the spirit of the baroque been so alive in recent art as it now seems to be in the field of jewelry. I am speaking not so much of that aspect of the baroque that is crowded and filled to the breaking point with layers-upon-layers of material but more the intellectual dimension that challenges conventional genres and also embraces complex ideas, theatricality, representation, humor and even caprice. Like a maquette by Bernini, the work featured at Adair Margo's "Sculpture to Wear" exhibition would seem to have fared as well as a part of a stage performance or, if situated in the landscape, as an architectural conceit, yet in their comfortable human scale the pieces demanded a familiarity and closeness denied by architecture and the theater.

For instance, the importance of the musical aspects of jewelry was sensitively demonstrated by the jingling units of Rachelle Thiewes' bracelets and necklaces and the twisting rhythms of Joyce Scott's elaborate beadwork. Architectural fragments were brought to mind by the spare, southern Mediterranean colors of Beverly Penn's miniature walls, windows and doors, while William Harper's rich enamels suggested the interior of a Pasha's palace or the elaborateness of an Ottoman manuscript illumination. Kate Wagle's Image of Perfection stared, with elegance and directness that permanence and mutability, solidity and fragility are often found in the same moment and substance.

While each piece clearly functioned individually, none of the artists were satisfied with only the creation of a hermetic work. All five referenced something outside of simple material manipulation and esthetic form. Thus the resonances of the imagination added to the inherent richness of the traditional physical elements of wearable art. Penn's combination of polished and patinaed copper were three-dimensional duotone sketches of the sights she witnessed on a recent trip to Spain. Joyce Scott's caricatures of various types of people, Married and Moslem Couple, and her comic earrings and necklaces combined the colors of juju fruit candies and costume jewelry into mini-narratives about human relationships and internal psychological struggles.

Harper's cloisonné enamels captured the images in a child's dreams after having heard the stores of 1001 Arabian nights: dazzling snakes and the brilliant striations of exotic mountains, all contained in a palm-sized brooch or a sword-shaped pin. Rachelle Thiewes chose to display her Silent Dance Series, on life-sized photographs of models to remind viewers of the importance of movement and physical interaction, which much contemporary metalwork demands.

Kate Wagle created the most confrontational piece with her metal "installation." A framed sheet of gold and images of a rose, a diamond, a cocoonlike pod, an acorn and a diving figure stamped in silver and pinned to the wall created an odd, yet intriguing visual poem. Its anti-traditionalism posited questions that played an interesting counterpoint to the other works in the exhibition.

"Sculpture to Wear" affirms much of the recent critical discussion concerning the breakdown of the traditional separation between painting, sculpture, metalwork, performance, et. al. The five artists included in the roster of "Sculpture to Wear", like the artists who preceded the modern period, seem to know that an object is not always only an occasion for formal analysis, often it is only the beginning of long and meandering consideration of the richness of image, substance and the imagination.

Frank C. Lewis is a critic and art historian living in Milwaukee, WI.

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

1990 Metals Invitational Exhibition

Haynes Fine Arts Gallery

Montana State University, Bozeman, MT

September 10 - October 19, 1990

by Ken Bova

It was one of my favorite places, filled with anything anyone who worked with their hands would want. There were 40-foot aisles filled with electrical parts, hand tools, gloves and garden supplies, boots and brass widgets. There were some strange things in those aisles. Standing in front of a bin of odd-looking brass and steel contraptions with moveable parts and springs, I once found myself thinking: What is this? Is it a tool or a part for something else? Out on North 7th Avenue in Bozeman, Montana, Quality Wholesale was the quintessential hardware store. It had a lot of something for everyone, and it was fascinating, delightful and bewildering.

Group metalsmithing shows are a little like that. At Montana State University's Haynes Fine Art Gallery, about 15 blocks south of where Quality Wholesale used to be, the 1990 Metals Invitational Exhibition was held last fall. Featuring the work of 13 artists, it had a little something for everyone, and it, too, was, by turns, fascinating, delightful and bewildering.

Bewildering were the comments on the first day alter the show opened: "What's some of this stuff got to do with metalsmithing?" and, "l don't get it. Is it supposed to be jewelry or sculpture?" Sound familiar? Like the brass doodah in the hardware store, group shows sometimes present us with objects that are strange or confusing, objects that seem at once familiar and unknown. They provoke us into wondering and speculation. Perhaps it is because the artists themselves are wondering and speculating. Whatever the reason, this show had its share of mixed-media sculptural work that bore little if any visual heritage to traditional metalsmithing. Likewise, there was "jewelry" that was so huge and cumbersome that the thought of actually wearing it caused self-conscious grins.

It was not, however, only function and content that viewers responded to, but process and technique - how did they do that - as well. It was in this area that the exhibit provided fascination and delight. On display were functional and nonfunctional holloware pieces that demonstrated a sense of form, sensitivity to materials and a technical skill that, put simply, made them a pleasure to look at. There was jewelry that did the same thing; it was both wearable and visually exciting.

Was it jewelry or sculpture? What did this have to do with "metalsmithing?" Just how did the artist do that? These are perhaps the sort of questions curator and exhibition organizer Richard Helzer was eliciting. As head of the Metalsmithing and Jewelry Department of M.S.U.'s School of Art, and a long-time arts educator, Helzer knows the value of the questioning process. The exhibit was organized in part for the university audience, i.e., metalsmithing students. As a consequence, the diversity of work shown was no accident. It was designed to technically, visually and conceptually educate.

That brass and spring thingamajig in the hardware store wasn't a tool but an irrigation-system component that regulated water flow. (I finally figured it out, with a little help from a store clerk.) Like Quality Wholesale, the 1990 Metals Invitational Exhibition contained plenty to look at. And like that hardware store, it provided the opportunity to stand there, look and ask questions, to be fascinated, delighted and bewildered.

Ken Bova is a jeweler living in Bozeman.

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

National Metals Invitational

Galerie Mesa, Mesa, AZ

November 16 - December 15, 1990

by Barbara Cortright

First impressions: the exhibitors appeared serious about their work and their level of imagination and technique were uniformly high. Curator Jeffory Morris achieved his arm of mixing work by recent graduates - something like 40% of those exhibiting - and established artists with no feeling of "master and student." Overall, there was an emphasis on sculptural qualities, and a meditative aspect that is an apparent characteristic of this next generation.

For example, a totally freewheeling object, Zumb, by Lee Boroson, which seems wonderfully organic, curled in its case like an overgrown leek with an astonishing, burgeoning, mushroomlike head. Made of copper, aluminum and lead, which exuded a gray-green and, of course, ochre, it shouted of vegetation and the earth. As in Surrealism, paradox, where nonorganic materials that are immutable to time are used to convey the all too mutable cycle of growth, sharpens the sense of both.

A similar theme, very differently expressed, lies beneath Replacing Nature: Tea and Sympathy by Robert Farrell. Here, a teapot with severe precision lines had, on its base, a delicate frieze of irises inlaid in metal. Materials were sterling silver, copper, bran nickel and 18-karat gold. One thinks here of Yeats and the lines, "Once out of nature I shall never take my bodily form from any natural thing, but such a form as Grecian goldsmiths make of hammered gold and gold enameling."

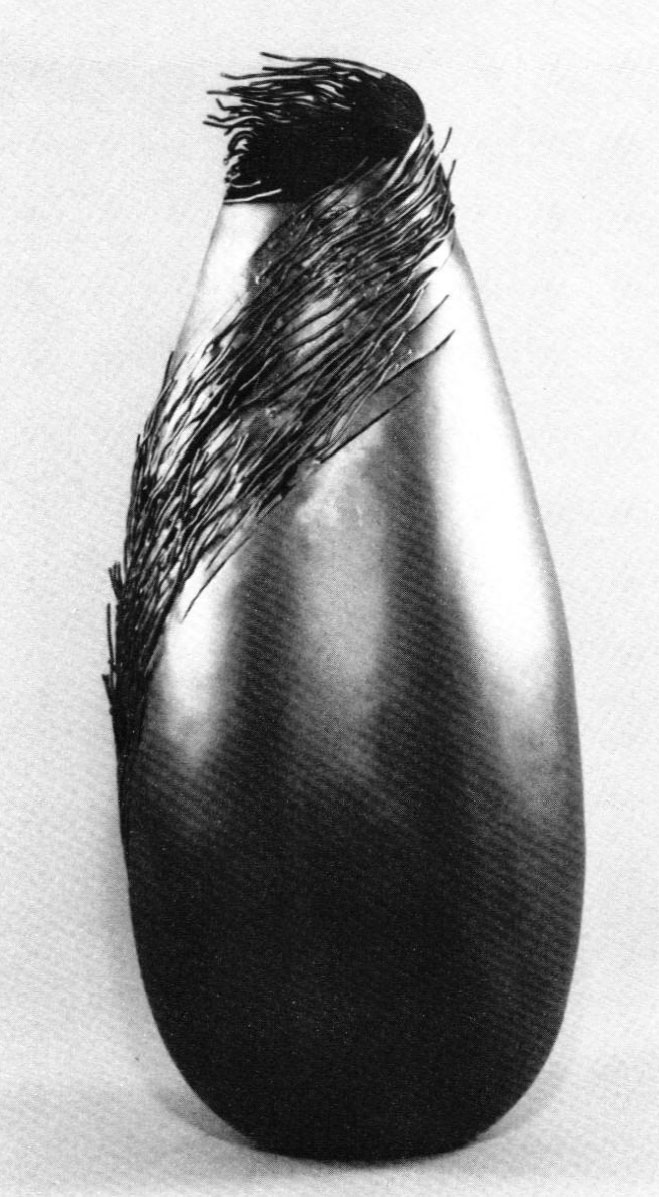

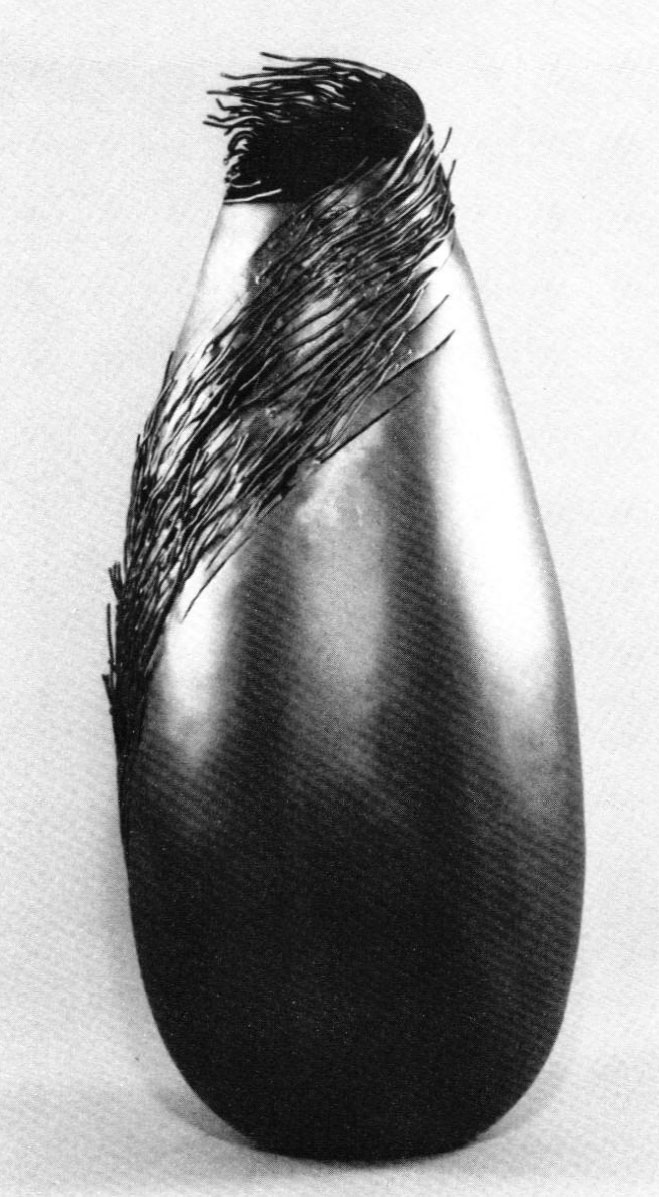

Then there was the elegant and simple Grass of May, an elongated copper pot encircled with a diagonal strand of copper "grass." A statement completed in few words by Michael Tom. Words were featured in the abstract, contemplative piece, Ten Bulls in a Quantum Field: Scene #5, by Harlan W. Butt. The quality of metal shines through in classic fashion, contrasting natural copper with color variations of red, yellow, bronze, shaded and textured with equally subtle spatial dynamics. The contrast between the implied physical sensations and the impersonal universality of the abstract form creates the tension.

Venus of the Furrow by Robly Glover is reminiscent both of Cycladic idols and Judy Chicago. In terms of expressing woman's fertility with the literal cleavage of childbirth it outdoes Judy and reaches back with some distinction to the Isles of Greece. Neat, brief, expressive, with its knife cleft down the middle of the goddess, Glover's piece, like other famous Venuses, might be enclosed in one's hand.

Completing the noteworthy entries was Keith A. Lewis's humorous Angry Face and three sculpturally impressive knives by Peter Jagoda. In short, an exhibition with range and depth, an exciting presage of things to come.

Barbara Cortright writes about art in the Southwest.

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

The Enamel Guild of New Jersey

The Newark Museum, Newark, NJ

January 13 - March 3, 1991

by Antonia Schwed

Under the aegis of Ulysses Dietz, decorative arts curator, the skillful display of the Guild's work, featuring five enamelists with six pieces each, seemed to underline the parenthetical comment made by Thomas Hoving in the December issue of Connoisseur magazine, where he refers to crafts as being "now equal in importance to the so-called fine arts."

Marilyn Druin, a cloisonné artist, had delicately crafted brooches that seemed to me right out of the Roman Empire. Her necklace with elaborate cloisonné beads is the kind of work you want to pick up and study from every angle. In addition, she exhibited three hand-raised little vessels, beautifully enameled with cloisonné details and cutout areas.

Peg Miller has come up with bowls in brilliant transparent colors combined with areas of firescale and opaque enamel. Two of the bowls exhibited have been cut and shaped, a technique that combines with the swirling colors to create a lovely wavelike quality.

Marian Slepian, that master of the "cloisonné painting" had six pictures hung along one well. If her enamels were purely enamel painting they would be outstanding, but when you add to the painted quality her elaborate cloisonné outlines, the result is truly stunning. To me, one of the problems of cloisonné has always been a sort of tightness, a constraining quality, but Slepian overcomes this completely and her cloisonné lines flow almost as if done with a brush. Her opera painting combines high drama with great colors. A larger picture, entitled "Pedestrian," I also thought particularly evocative.

Katharine Wood had a dynamic range of work. In her display case there is an enamel mask with movable eyes, staring out from a small crate. Also, there are two, small, dazzling champlevé pictures, sort of Jungian portraits of two figures, each with a background that is a mystical melage of animals and trees. They are called Chac I and Chac II, referring to the ancient rain god of Mexico. On one side other case is a collage-wall-hanging, representing a dramatic new line of work by Wood in which she combines enamel pieces with black wood-forms that give a sculptural quality to the work.

In all, this exhibit was a great boost for modern enameling. Too long misunderstood and overlooked, often deemed a medium to be used in summer camp for a hobby, in reality enamel is one of the most exacting and beautiful media. As a medium it is indeed technically perverse and difficult, but in this exhibit it is being successfully used for the expression of artistic conceptions. The artist dedicated to enamel as his/her medium can be encouraged by and proud of the exhibit at the Newark Museum.

Antonia Schwed is an enamelist living in New York City.

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

Christopher Darway

Morris Museum, Morristown, NJ

November 11, 1990 - January 6, 1991

by Patricia Malarcher

Christopher Darway's solo exhibition opened a window on the workings of a problem-solving mind. The 35 pieces, a combination of jewelry and sculpture, projected the cool, classic clarity of works in which design rather than expressiveness is the prime determinant. However, this was tempered, sometimes contradicted, by the warmth of a playful intelligence.

Darway is a master of materials and skills related to auto shops and hangars as well as metal studios. Working with an even-handed treatment of fine metals and industrial components - for example, rubber O-rings, wire mesh, plastic tubing, aircraft cable - he produced the works on view within the past two years. His confidence in shifting from gold to plywood, to foam to paper and beyond, as well as his use of processes such as riveting that are unusual in jewelry, reflect his training in industrial arts. He is also a master of invention who exploits, with obvious delight, the permutations of design elements and their adaptation to function. This approach to design informs his work with its own personality.

Although this show is relatively small for a jewelry presentation, it is replete with ideas. Every form suggests the answer to a problem and prompts the viewer to examine it from different perspectives. Many designs have subtle overlays of reference. For instance, a flexible "2-dot bracelet," a multiplied module of tiny connected discs, looks like a chain of molecules. Much of Darway's work calls attention to the relationship of geometric and organic form.

In the simplest bracelets of linear circles, squares and triangles - their structure recalls cookie cutters - there is a seamless fusion of functional necessity and esthetic value. Unobtrusively hinged, their walls are held together at the openings by Velcro-covered flanges. The line of black created by the Velcro at the juncture provides the one critical relief from the smooth austerity of brushed sterling.

While those and another group of bracelets in sterling and foam cord were pared to the minimum, some pieces were designed to be integrated into sculptural environments when not being worn. For instance, a three-sided ring - it was shaped like an "A-frame - became a pitched "roof" atop a stand built of columns. A slim gold choker, unclasped and opened, was displayed on a base as a lyrical line that engaged the separated sections of the clasp as points of tension. For storage, a segmented fold-formed bracelet was accompanied by a rocket-shaped container with a drawer. This changed the normally four-cornered bracelet into a train, reminiscent of a child's toy, of convex gold forms with intricate hemispheres of wire screen as couplings.

Darway's penchant for formal alterations was most fully demonstrated in a group of five objects, each in a different material and scale, in which an S-shaped curve was the organizing principle. This unit, repeated, snaked horizontally into a cold-enameled sterling pin; in a bronze table sculpture it was broken down and stacked; in the largest piece, it was translated into a skeleton of balsa wood supporting a paperish "silkspan" shell, constructed like a model airplane.

At this museum site, it was appropriate that the work be displayed with an emphasis on form rather than function. However, a few pieces, such as the triangular ring, invited me to wonder how they mesh with human form.

While the exhibition observed Darway's 1990 craft fellowship awarded by the New Jersey State Council on the Arts together with his nomination as a Distinguished Artist of New Jersey, it was but a teasing sample of his work. Beyond his versatility with materials and his finely tuned sense of design, Darway has proven elsewhere his ability to carry an idea from miniature to monumental scale with all the needed adjustments. The series based on the "S" curve alluded to this, but seemed rather like an exercise. The lobby of the Morris Museum was inadequate for a full-scale presentation of his work, but one could hope that such an exhibition lies ahead.

Patricia Malarcher is a fiber artist and craft critic.

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

William Strasser

Viewpoint Gallery, Carmel, CA

Fall 1990

by Anne Telford

Jeweler William "Willy" Strasser is an original as his comical yet thought-provoking creations. The native Californian works out of a vintage Airstream trailer parked behind his modest Santa Cruz house. The studded metallic interior is chockablock with the materials Strasser uses for his jewelry and the visual references that inspire his work. Since 1973 he has been making very modern jewelry, often based on ancient symbols. His layered pins, earrings and bolo ties combine elements of Oceanic art with tropical symbols, Cubist references, skulls inspired by Mexican dia de los muertos (day of the dead) ceremonies and the raw, vigorous style Picasso cultivated after his trips to Africa. They often feature striking, primitive faces.

His pieces are constructed of semiprecious, nonferrous metals - silver, brass, copper and occasionally gold, although its cost prohibits wider use. "All my jewelry has combinations of different metals as far as my palette goes," Strasser explains. "I use the metals as colors and the colors are used in contrasting fashions to make the features come out or go back in, and for the color of the hair." He prefers the look of oxidized copper to copper sprayed with plastic to prevent the surface from being marked by fingerprints. He says of this favored metal, "It's really unstable in the polished form but let it oxidize and it has this impervious, kind of unchangeable patina."

Strasser doesn't get bogged down in the "is-it-fine-art?" school of jewelry making. He feels some jewelers lose sight of the end result when they try to "make their jewelry to be more like art," ending up with necklaces that resemble breastplates. Although he will occasionally make pieces "that are more on the statement side" for models or clients who wish a dramatic piece, he keeps his jewelry functional as well as decorative.

For this, his first one-man show, Strasser spent six weeks creating a group of wall plaques that took his jewelry concept several steps farther. He used drawings from a Mexican magazine that dealt with drug addictions as inspiration for some of these larger-scale pieces that ranged from jewelry-size to 1½ feet by 2 feet. "There was something really absurd about it and kind of misinformed. It struck me as being really funny but yet at the same time it was an anti-drug statement," Strasser explains. One plaque depicts a man with a crazed expression looking at a jar of LSD he is holding; underneath this image are the words una droga terrible (a terrible drug). Wrestlers, suggested by lucha libre (free wrestling) magazines he buys in Watsonville are the subject of several plaques. The masked images are fierce, compelling and imbued with Strasser's unique sense of humor. He points to one: "This guy is Alcatraz, the prisoner. He's got jail bars on his eyes." All the plaques bear funny titles such as The Doggie Expo, decorated with stampings of poodles; Johnny Blaze Meets the Tiki God, based on a comic book character who transforms Hulk-style into a blazing skull; and Willy's Novelty Company, a name he's created for a fantasy roadside attraction store.

Strasser's shapes are sensual and organic; his long totemic heads with overlaid and etched features have a timeless appeal. He often incorporates commercial metal stampings into his work. "I've tried to take the stamping thing to the limit," he says. "Everybody can go in a buy stampings. You can get really tired of looking at just a plain old guitar or some chickens or fish." In Strasser's hands they are anything but plain. His own twisted genius combines wildly disparate stampings into metal comic book strips. Indians dive into kidney-shaped swimming pools, Jesus is mock-crucified by guitars, surfers hang ten through a cosmic landscape of saws and crosses and one series depicts a headless surfer shooting through a conceptual circular "tube." It's natural for Strasser to include surfers in his circus of characters. He's been an avid surf enthusiast for years; it's a way to unwind from the hours of meticulous detail work.

Once he arrives at a theme he will do a number of variations on it. He has no lack of ideas and he enjoys embellishing an existing design. Although Strasser has an associate of arts degree from a California junior college, he is largely self-taught. He constantly pushes the boundaries of both his craft and his subject matter. The world is full of iconic images; television news reports produced a series of screaming laces pins and elements of contemporary culture, here and abroad, continue to provide inspiration. And while Strasser considers his work to be whimsical and light-hearted, it is also a metaphorical statement on life in the 90s.

Anne Telford is a writer living in San Francisco.

You assume all responsibility and risk for the use of the safety resources available on or through this web page. The International Gem Society LLC does not assume any liability for the materials, information and opinions provided on, or available through, this web page. No advice or information provided by this website shall create any warranty. Reliance on such advice, information or the content of this web page is solely at your own risk, including without limitation any safety guidelines, resources or precautions, or any other information related to safety that may be available on or through this web page. The International Gem Society LLC disclaims any liability for injury, death or damages resulting from the use thereof.

Related Articles

Jewellers’ Objective Attitude Towards Designing

Bruce Metcalf: Between Darkness and Light

CAD/CAM: Creating a Class Ring – Part 1

GZ Art+Design 2004 5 Spots

The All-In-One Jewelry Making Solution At Your Fingertips

When you join the Ganoksin community, you get the tools you need to take your work to the next level.

Trusted Jewelry Making Information & Techniques

Sign up to receive the latest articles, techniques, and inspirations with our free newsletter.