Master Metalsmith John Paul Miller

7 Minute Read

A provocative dilemma evolves when one attempts to use the written word to describe things which are in essence ineffable. This challenge presents itself when trying to describe the artist/teacher John Paul Miller. He rarely makes direct statements for publications or publicity, yet is wonderfully free and open with his time to an inquiring student or friend. He is not a bigger-than-life charismatic personality but rather a quiet, shy man, easily overlooked in a group.

John Paul is not one for bathing in the limelight, so we will not find him seeking administrative positions in art or craft organizations. Yet he is known by all who follow the jewelry field, for his work is internationally recognized and honored. He believes in the value of experience and of doing rather than of talking. "My purpose as an artist craftsman is simply to enjoy the experience of working to bring a degree of presence, life and vitality to a form," he simply states.

However, metalwork is only one of many art media that John Paul enjoys. For many years he won awards as a painter and watercolorist while practicing metalsmithing. Jewelry and the visual arts axe not his first love, but come after the appreciation of music and nature. John Paul is a well-known exhibition designer and a naturally gifted teacher. During a visit to his home in Ohio I asked him, "Why do you teach?" A wry smile crossed his face: "Teaching allows me a good period of free time each summer to do the most important things." This meant that on the best summer days he would be hiking in the Rockies along a secret path toward a favorite alpine lake, listening to solo piano music on his Walkman recorder.

During a springtime visit in the Pacific Northwest, we shared a ferry ride across open water on a very cold day. John Paul looked into the distance until the cold air blinded his eyes with tears and still he did not want to leave the view. Later that day we strolled on a beach of sand and rocks where Miller spent a great deal of time standing over one small tide pool. He brought me a tiny crab to share the splendor of its design. Soon afterward he commented on the composition of a distant cliff-face arrangement. I saw then that he observed and responded to not only the distant but also the close-at-hand with equal enthusiasm.

Nurtured by parents sensitive to the arts, John Paul was supported in his earliest artistic expressions. He was stimulated by teachers such as Kenneth Bates and Viktor Schreckengost at the Cleveland School of Art, growing up in a city with many active craftsmen operating in a climate of public support. In 1936 at the age of 18, John Paul enrolled in the Cleveland Art Institute where, by forced alphabetical student seating, he shared all the classes of his first two years with another Miller, Frederick A. Though of different personalities the two Millers formed a friendship in a climate of artistic support which has fertilized their careers through 40 years to this day. In fact, it is Fred Miller who has to a large extent made this article possible by providing rich and lengthy reminiscences of the friendship. The story of Fred Miller's evolution and career is a worthy study in itself and will be the subject of a future article.

As a student, John Paul was very talented in all aspects of the Institute curricula, with a preference toward watercolors, egg tempera and design. While Fled was completing his first official jewelry class he showed John Paul how to do silver solder with blow-pipe and alcohol lamp. Although John Paul showed an immediate affinity for metalwork, his first love was still watercolors, an idol at the time being John Birchfield.

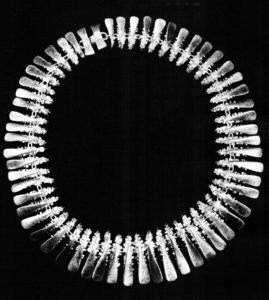

- Fragments brooch, 18k gold, 1964

Photo: The Cleveland Museum of Art; John Paul Miller; National Museum of American Art, Smithsonian Institution

After serving in the Army during World War II, John Paul Miller returned to teach design at the Cleveland Art Institute in 1946, while Fred Miller became a designer at Potter and Mellen Company, a fine furnishings and design firm with a complete silversmithing and jewelry shop. As they spent evenings making jewelry at Fred's bench in the shop, they enjoyed the special inspiration that comes from working together. During these years, John Paul used the summers between school terms for travels in the mountains of the western United States. He found favorites in the solitudes and grandeur of Yosemite and in the Wind River Range of Wyoming.

Both Millers attended the early Handy & Harman silversmithing workshops in New York where the Swede Baron Eric Von Fleming provided a rich source of inspiration. They found he was a designer more than a craftsman, encouraging the doing over the cerebrating. The Millers made a film on the stretching process and contributed to some publications for Handy & Harman in 1952. About this time John Paul sold one of his earliest major granulated gold pieces, a beetle form, to the Cleveland Museum of Art. It was the result of many years of personal experimentation in gold granulation, starting in the late 30s and stimulated by photos of the work of Elizabeth.

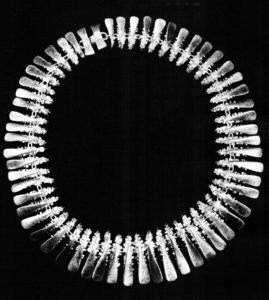

- Clockwise from top left:

Polyp pendant/brooch, 14k gold, 1963

Hermit Crab pendant/brooch, 14k gold, enamel, 1981

Thorns pendant/brooch, 18k gold, 1976

Fragment, 18k gold, 1972

The middle 1950s marked a period of continual expansion for John Paul Miller. An old teaching record from the Institute states that he has taught general techniques, color, design, drawing, watercolor, painting, jewelry and silversmithing. One student advised to explore metalsmithing on a John Paul hunch was John Marshall, who is to this day very thankful for Miller's perception. John Paul has been the Art Institute's Gallery Designer since 1946, overseeing all installations, especially student shows. Over the years he produced three films on silversmithing and jewelry, including a color film on granulation, featuring extraordinary close-up photography of the process. He still is a photographer, avid fisherman, hiker, climber, animal and bird watcher, gardener, cook and a voracious reader.

From his early days at the Cleveland Art Institute to his last years teaching, John Paul has demonstrated that anything worth doing is worth doing well. Fred Miller has said that it is a tragedy that John Paul is so good at so many things; a tragedy that so much of his time is demanded for projects outside of jewelry. John Paul has filled countless sketchbooks with his drawings for jewelry. If a customer brings in a particularly outstanding stone John Paul might do some beautifully rendered sketches of a proposed design. However, the majority of his clients must be content with a position on a long waiting list.

As a teacher John Paul expected only the best from his students. A student had to be committed to meet him halfway and then John Paul would return the energy many times. Creativity was approached in his classes as self-motivated research, catalyzed by his distinct input. He would teach his sophomore design class by showing students slides on the concept of space. In exhibiting clear and pronounced opinions about what he was showing, he encouraged students to do the same in their work. John Paul stressed a conscious looking/designing attitude above and beyond the easier and more common subconscious methods. He helped with down-to-earth advice on the money versus art dilemma, lifting the weight of quandary for many career artist-craftsmen. With uncanny patience John Paul showed students how to be responsible to themselves and their work, in short, how to establish self-respect.

John Paul has recently pulled out of teaching to allow more time to pursue his own work. It is a pleasure to watch him at work in his studio, a bright, cheery space he shares with Fred Miller. His approach is steady and direct with a minimum of wasted motion, lacking in useless "in-between" times. He is now able to take more trips, especially to Europe and Scandinavia. He has said that he wishes he had gone to Europe during his youth for the inspirations found in the art of older, richer cultures. He warns any young person to beware of the captivating draw of America's western mountains. He still goes to his favorite places among them, often bringing a younger guest or student to share in the serene glories. My parting image of him does not find him calmly sitting at this workbench, tweezering delicate gold constructions, rather, I see him peacefully paddling a canoe, in a composed attitude of attention, resilient to the forces that move us all.

You assume all responsibility and risk for the use of the safety resources available on or through this web page. The International Gem Society LLC does not assume any liability for the materials, information and opinions provided on, or available through, this web page. No advice or information provided by this website shall create any warranty. Reliance on such advice, information or the content of this web page is solely at your own risk, including without limitation any safety guidelines, resources or precautions, or any other information related to safety that may be available on or through this web page. The International Gem Society LLC disclaims any liability for injury, death or damages resulting from the use thereof.

Related Articles

Deborah Aguado: Use of Image and Enigma in Jewelry

Natalie Paul Exhibition Review

Kathleen O’Rourke

The Artemis Medallion

The All-In-One Jewelry Making Solution At Your Fingertips

When you join the Ganoksin community, you get the tools you need to take your work to the next level.

Trusted Jewelry Making Information & Techniques

Sign up to receive the latest articles, techniques, and inspirations with our free newsletter.