From Limited to Mass Production of Jewelry

8 Minute Read

Like many university-art-department-trained craftspeople of the 50s, I was educated to be one-of-a-kind snob, sneering at production people. They were crassly commercial; we were unique, creative, artistic. We labored long and cautiously, often taking five months to produce one museum-quality masterpiece. We entered shows, won prizes, entombed our oeuvres in glass cases, gave them to our mothers or sold them to acquaintances (assuming we could bear to part with them).

Times have changed; it is no longer a disgrace to admit that one needs money. We have expensive habits like mortgage-paying, clothes-wearing and sending children to college. It is possible to combine the satisfaction of doing what we know and love with the comfort of bills being paid.

My mind-set was abruptly altered in the summer of '81 by a challenge to design a collection of jewelry for Bloomingdale's. In six weeks, with one assistant's help and working 12 hours a day, 7 days a week, we manufactured 275 pieces and delivered on deadline.

Attitude: Production can be fun

First comes a change in attitude. Speed and efficiency are not necessarily synonymous with shoddy and ugly. Remember Dr. Spock's Baby and Child Care? Did you ever flip to the back of the book and read shortcuts for twins and triplets? What an eyeopener! You don't have to be so careful; babies are remarkably resilient. Sometimes they even take care of themselves.

So it is with production jewelry.

Getting Started

- Take a good design; simplify it; strip it of unnecessary parts.

- Omit some construction steps. Do you really need to file with #2, a #4, emery paper, etc.? Try Bright-Boy and Graystar.

- Make 13 of them. One is to ruin or lose under the polishing bench. The others will arrange themselves in matching pairs. Voila: earrings, 6 pairs. Marketable.

- Do this faster than you think you can. (See below.)

- Assume that these pieces are "items," not precious babies; i.e., they are for sale, not entrusted to your care for years.

- Expand the design into a family related by a specific feature. Include at least: two earring styles, one on-ear, one dangle (post or clip); two neckpieces, one a collar, one linked; two or three bracelets, cuff or linked; a pin/pendant and belt buckle—all offered in large, medium and small. This is a "line."

System

(I am eternally grateful to Ronald Hayes Pearson for showing, in his first teaching workshop in Washington, his working file cards with metal models, both finished and in progress, attached.)

- It is essential when designing a "line" to keep accurate records of each time-consuming process performed, success or failure. (See examples of 5 x 8 cards in Philip Morton's book, p. 261.)

a. Note every facet of fabrication. This is time-consuming initially but pays off later.

b. Record the effects of varying thicknesses, types of metals, placement in the rolling mill, whether forging started at the midpoint or 1½" from the ends, etc.

c. Trace outlines of the work in stages. Use different inks, superimposed, for each pass. (Could step three have been taken farther without damage?)

- Reward yourself: promise that you may call a friend after doing just eight more whatevers.

- Experience the joy of production. It is quite amazing how, during a series, the pieces take over and begin making themselves, suggesting variations on the theme and actually helping you.

- Once you have a winner, consider casting, RT Blanking or chemical etching to produce the basic form, then tumble-polishing to speed up the finishing process.

- Buy a dozen cross-locking tweezers; solder findings in a row.

- Play games with time studies. If you can saw four shapes in 30 minutes, could you eliminate one concave curve, lay them out more efficiently and finish in 15?For example, I did an elaborate time study on one of my most popular earrings for a catalog order: 24 pairs of sharks' teeth. That meant producing 25 mirror images (one each to ruin or lose, of course.) Results were not encouraging.Twenty-two separate steps were performed on 100 pieces of 23-gauge Nu-gold, from "layout" to "shipping." Only two steps involved soldering, but eight required trimming, filing and/or polishing Total: 1,010 minutes or 16½ hours of hands-on work, roughly 40 minutes per pair. At $23 wholesale, this was obviously labor-intensive and not cost effective. (Mental note: Could I call it PR/advertising? Make them in sterling and raise the price?)On the other hand (ear), another item, the "potato chip," has gone through several incarnations in four and a half years, and its production time has diminished from 30 minutes to 8. Shall I then lower its price? Absolutely not; profit has to come from somewhere.

Business Aspects

- Assume that you will succeed; act on that premise.

- Invest in business cards, forms for orders and invoices, personalized stationery and envelopes. (Call NEBS, 800-225-6380, for catalog with reasonable prices.)

- Open another bank account out of which you will pay and receive every penny relating to The Business. (No sneaking food money from the profits, please. You have to eat anyway.)

- Learn bookkeeping—or at least condition yourself to itemize expenses and income monthly. (See IRS Schedule C, Form 1040, for approved categories before you start.)

- Check state and local regulations re: business in the home, personal property tax, ad infinitum. Prepare to spend several days with people who understand little, care less, and possibly give incorrect information. Remember you are responsible for the accuracy of your paperwork.

- Inventory all expendable materials: metals, findings, gems, etc., as well as small replaceable tools (three-year life) and large depreciable machines. Know when you bought them and what you paid.

- Buy 50 file folders with sides ($.56 each, Ginn's) on which to inscribe (in pencil) names of suppliers, buyers, potential buyers, reps, et al. (You cannot know in advance which ones will become inch-thick with problems or, happily, reorders and timely payments.)

Marketing: Do you really want to be successful?

- Know your market; target your market, all advice-givers say. Catch-22—this is very hard to do. It's like telling a 16-year-old, "I'll give you your first job if you give me references from three previous employers."

- Choose a jewelry field:

a. Fashion—"Arrived," thanks to the groundwork of Robert Lee Morris and others and recent publicity in Metalsmith: $45-$1,000 retail.

b. Fine—Becoming more production-oriented. (Read articles on Paloma Picasso and Angela Cummings in Vogue, Connoisseur, W): $300-$3,000.

- Reserve money for start-up costs; payment is running 90 days. Everyone has a good excuse, including you.

- Contact potential buyers by:

a. Trotting around yourself. The surprise effect sometimes works.

b. Taking a booth at a jewelry trade show (JA, FAE, ACE),

c. Hiring a Rep (See Metalsmith, Winter 86, p. 19).

- Learn the vocabulary: "What are your price points?" "Let's write." "Have you a minimum?" Yes—$250 or 5 pieces.

- Take more samples than you expect to sell. Buyers like to have something to reject.

- Try to sell outright, wholesale. There is much less grief and paperwork. (See numerous articles in The Crafts Report.)

- Be emotionally and organizationally prepared for volume orders.

- Deliver on time: usually 4-6 weeks. (Repair and return rapidly. Blame problems on defective findings, usually true.)

- Do NOT make surplus inventory. Buyers always want it "just a little bit smaller/larger, with a clip instead of a post . . ."

- Price competitively with the competition. Forget formulas. If you think you're losing money on an item, speed up production, find a more compatible outlet, or discontinue it.

- Have handouts for ease of ordering and publicity, including:

- Copies or sketches of the pieces, not so clear that they can be ripped off, but good enough to remind the buyer of your samples.

- Wholesale price list with logical style number and terms of payment, i.e., COD first order; Net 30 subsequent.

- Signature card with use and care information. (Ask which stores discard these and use their own—saves time and money.)

Disappointments

- Rejection—real or imagined. Buyers are "too busy," "just stepped away from the desk," are "out in the market," "just spent this season's money" . . . ("Yours are the only original ideas in this show; unfortunately my customers want pink rhinestones now"). It's their loss, isn't it?

- Someone else invents a piece nearly identical to yours, gets credit before you do. Forget it.

- Another designer discusses one of your creations with you at a show. Later you see it expanded into a line in four colors under his/her name. (Not only is it an outright rip-off, but you also feel stupid for not recognizing its potential yourself.) Use biofeedback to lower your blood pressure.

- Dubious theft—"One pair of earrings is missing from my order—we've looked everywhere—I'll just take it off the check." You know damn well you shipped it, and it hasn't turned up anywhere in your reasonably clean studio. Then you hear that the store is having financial difficulties. Tell people.

- Surplus ideas—You find yourself constantly squelching the urge to design items totally out of the current line's character. Make one sample of each and out it aside for next season or year. After all, it would be foolish (in this business) to offer all ideas simultaneously, looking like seven different people, later to expand upon them and appear to imitate someone, this time yourself!

The Five-Year Plan

- Have one. Set goals, immediate and long-range.

- Prepare to modify them to adjust to reality.

- Share information, techniques and resources. What you give comes back compounded, eventually.

PS :

Of course, if I had followed all of this advice perfectly for the last four years, I would be rich and famous now. Don't do what I do; do what I say . . . and Good Luck!

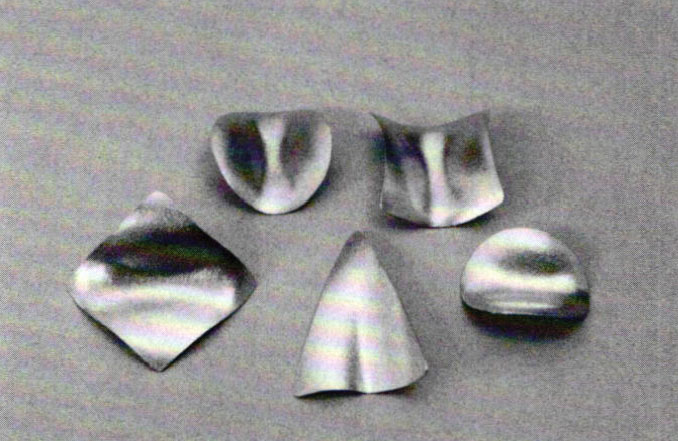

Pictures are Yvonne Arritt production jewelry; pins, cuffs, and Scarf Swirl collar, cuff and earrings, sterling silver; roll printed and formed. Photos: Betty Helen Longhi.

Yvonne Arritt is a fashion jewelry designer in McClean, VA whose work is exhibited nationally. This article reflects five years of experiences in trying to follow the advice of assorted teachers and professionals and a strong wish to help prevent others from "reinventing the wheel."

You assume all responsibility and risk for the use of the safety resources available on or through this web page. The International Gem Society LLC does not assume any liability for the materials, information and opinions provided on, or available through, this web page. No advice or information provided by this website shall create any warranty. Reliance on such advice, information or the content of this web page is solely at your own risk, including without limitation any safety guidelines, resources or precautions, or any other information related to safety that may be available on or through this web page. The International Gem Society LLC disclaims any liability for injury, death or damages resulting from the use thereof.

The All-In-One Jewelry Making Solution At Your Fingertips

When you join the Ganoksin community, you get the tools you need to take your work to the next level.

Trusted Jewelry Making Information & Techniques

Sign up to receive the latest articles, techniques, and inspirations with our free newsletter.