Henry Steig

11 Minute Read

Everyone knows the famous picture from the film The Seven Year Itch, of Marilyn Monroe standing on a New York sidewalk, her skirt blown up by on updraft from the subway grate below. However, not everyone knows that at that moment she was standing in front of Henry Steig's jewelry shop at 590 Lexington Avenue.

Henry Steig was a man of many talents. Before he became a jeweler, he was a jazz musician, painter, sculptor, commercial artist, cartoonist, photographer, short story writer and novelist.

"Henry was a Renaissance man," says New Yorker cartoonist Mischa Richter, who was Steig's good friend and Provincetown neighbor.

Henry Anion Steig was born on February 19, 1906, in New York City. His parents, Joseph and Laura, had come to America at the turn of the century, from Lvov (called Lemberg in German), which was then in the Polish port of the Austro-Hungarian Empire. Joseph was a housepainter and Laura, a seamstress.

They had four sons, Irwin, Henry, William and Arthur, all of them versatile, talented and artistic. William Steig is the well-known New Yorker cartoonist and author-illustrator of children's books. lrwin was a writer of short stories for the New Yorker. Arthur was a painter and poet whose poems were published in the New Republic and Poetry magazines.

William Steig recalls, "My father and mother both began pointing and become exhibiting artists after their sons grew up." In the May 14, 1945, issue of Newsweek magazine, an article was published about an exhibition, "possibly the first one family show on Art Row (57th Street)" at the New Art Circle Gallery. It was called "The Eight Performing Steigs, Artists All." Included were paintings By Joseph and Laura Steig; drawings and sculpture by William and paintings by his wife, Liza; paintings by Arthur and his wife, Aurora; and photographs by Henry and paintings by his wife, Mimi. The only brother not included was Irwin, "the only non-conformist Steig," who was working at that time as advertising manager of a Connecticut soap manufacturer.

In the article "the brothers attribute the family's abundance of good artists to the fact that we all like each other's work…get excited about it. Whenever anyone starts they get lots of encouragement. Joseph Steig adds, 'Painting is a contagious thing. If you lived in our environment, you would probably point.'"

The first four pages of Henry Steig's catalog from the late 1950s. Courtesy Michael Steig

Henry Steig grew up in this extraordinary environment. The family lived in the Bronx. After graduating from high school, Henry Steig went to City College (CCNY). After three years he left to study painting and sculpture at the National Academy of Design. He was also an accomplished musician, playing saxophone, violin and classical guitar, and while he was in college, he began working as a jazz musician. From about 1922, when only sixteen years old, until 1932 he played reed instruments with local dance bands.

After four years at the National Academy, Steig worked as a commercial artist and cartoonist. He signed his cartoons "Henry Anton" because his brother William was working as a cartoonist at the same time, for many of the same magazines. From about 1932 to 1936, Henry Anton cartoons appeared in Life, Judge, New Yorker and other magazines.

Steig began a writing career in 1935 that lasted until about 1947. He became very successful and well known as a short story writer, with stories appearing regularly in Saturday Evening Post, New Yorker, Esquire, Colliers and others. They were often humorous tales about jazz and the jazz musicians who populated the world of music in the roaring twenties. Other stories were about his Bronx childhood. He also wrote nonfiction magazine pieces, including a New Yorker profile of Benny Goodmon and jazz criticism. Several of his nonfiction articles were illustrated by William Steig.

In 1941 , Alfred A. Knopf published Henry Steig's novel, Send Me Down. The story, told with absolute realism, is about two brothers who become jazz musicians in the twenties. On the book jacket, Steig wrote, "Much of the material for Send Me Down was gathered during my years as a jazz musician playing with local jazz bands and with itinerant groups in vaudeville and on dance hall tour engagements. Although I was only second-rate as a musician, I know my subject from the inside, and I believe I was the first to write stories about jazz musicians, based on actual personal experience." His son, Michael, recalls that there was some interest in making a movie of the book. "My father told me that John Garfield wanted to play the lead character."

Steig did go to Hollywood in 1941, under contract to write screenplays. He was going to work with Johnny Mercer, the songwriter. After the bombing of Pearl Harbor on December 7, he returned to New York. "He undoubtedly would have returned anyway," says Michael Steig. "He was not happy with the contract his agent had negotiated for him." Mischa Richter odds, "Henry was very unimpressed with Hollywood."

In the early 1940s, Arthur Steig started a company called Steig Products. "In making artist's colors and inks," says William Steig, "Arthur solved problems that professional chemists were unable to solve."

Henry Steig was a partner with his brother in Steig Products from about 1945 to 1948. "Because the business (which later became quite thriving and still exists today) did not make enough money for both partners, my father stepped out," says Michael Steig. "How he hit on jewelry making, specifically, I don't know, but he had to consider how he might put his creative talents to work in order to make a living."

"I don't know how Henry got into jewelry making," says William Steig. "Henry was into many things. Even as a kid, when most of us were into sports, Henry was always making things: kites, rings mode of horse hair (pulled from horses' tails) and such."

By the late 1940s there were several talented craftsmen who had already established shops in Greenwich Village. Among them were the studio jewelers Sam Kramer and Paul Lobel. Like Paul Lobel, Henry Steig come to jewelry making as a mature and accomplished artist. Throughout his life, in addition to designing and making jewelry, Steig continued to point and take photographs and to exhibit his work in galleries.

"The only modern jeweler that I can recall my father knowing personally at that time was Sam Kramer, and I'm sure there was little, if any, influence," says Michael Steig. "He did admire the jewelry of Yonny Segal, who had an exhibition of her work at the Museum of Natural History in the early nineteen fifties.

"Although my father did take one or two evening courses in jewelry making, this was not over any substantial time period. He learned the fundamentals and went on from there, on his own, so one could say he was largely self-taught.

"The first actual exhibition and sale of his work was in 1949 or 1950 at our apartment on West Ninth Sheet. In the summer of 1950, he rented a store at 200 Commercial Street in Provincetown, Massachusetts, which he continued to operate in summers until 1972."

Although he lived in Greenwich Village, Steig opened his first shop in midtown Manhattan in late 1949 or early 1950, at 51st Street and First Avenue.

Michael Steig remembers, "My father moved to 590 Lexington Avenue at 52nd Street a few years later, perhaps 1955, although I'm not certain.

"He never had a shop on West Fourth Street (where many of the New York studio jewelers were located), although Milton Hefling's store there, which mainly sold handmade leather handbags, did carry some of his pieces for a while in the nineteen fifties."

During the fifties, Steig worked primarily in handwrought sterling silver, although he did offer his designs in 14K gold. There is no typical Steig piece. He made jewelry constructed of flat forms combining geometric and biomorphic shapes. He also made pieces of twisted wire. His jewelry was mostly abstract, but sometimes his pieces were representational, drawing on plant or animal forms for inspiration.

A catalog from the late fifties illustrates dozens of his designs. For example, there is a brooch and earring set mode of sleek boomerang shapes. There are several bracelets that show his talent for combining ordered geometric forms with more improvisational organic shapes. All of his pieces are very sculptural. His sophisticated use of negative and positive space, his preference for the asymmetrical, and his ability to create tantalizing visual surprises demonstrate his highly developed sculptural sensibilities.

"Each piece of Henry's jewelry was a miniature sculpture," says Mischa Richter. "He was very jealous about his designs."

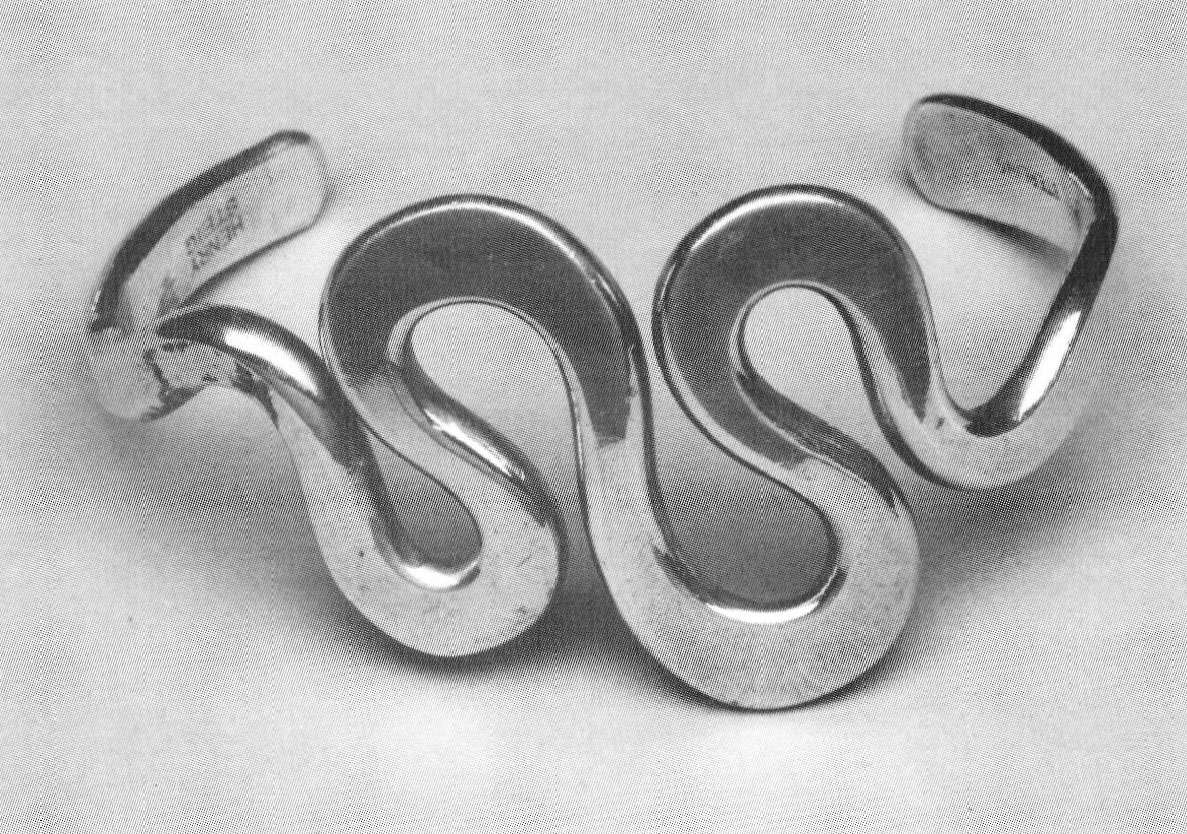

In Steig's twisted wire pieces, the wire has been hammered so that its surface modulates from round to flat. It was then shaped into complex curvilinear forms. In most of these pieces it is hard to visually follow the path of the wire from its beginning to its end. Reminiscent of the jewelry of Alexander Calder in the use of twisted and flattened wire, these pieces differ from Calder's in that they are more labyrinthine and lyrical. One piece in particular (see photo above) is a large bracelet of rhythmically looped wire that is light, unexpectedly flexible and remarkably comfortable to wear.

Steig occasionally used semiprecious stones in his jewelry, not as a centerpiece or dominant element, but to accent and contrast with the total design. Amethyst, carnelian, quartz crystal, green onyx, malachite and turquoise were among the cabochon stones that he used, as well as cultured pearls and hand-carved ebony. Michael Steig remembers that his father always bought unusual and unique stones from itinerant salesmen and would design a piece around a particular stone. Because he used odd stones, he often mode only one or two pieces in a particular design.

The jewelry of Henry Steig is elegant, visually light and flattering to the wearer. He took pains to make sure that the jewelry fit comfortably and was never overpowering. His sense of design was strong, but not formalistic and rigid. He knew that an overly designed piece of jewelry is boring and predictable. There is a sense of freedom, improvisation and surprise in his work but no piece was ever haphazard or sloppy.

Sylvia Roth, wife of New Yorker cartoonist Al Ross, bought a necklace from Steig in the 1950s, a one-of-a-kind piece made of silver, malachite and ebony. While she was in the shop with her husband and young son, Steig remarked on the fact that she wasn't wearing a wedding ring. She explained that her wedding ring had always been uncomfortable to wear. "It's just psychological," said Steig, and he proceeded to sell her a wedding ring that went with the necklace. She wears the ring to this day and considers the necklace her most unusual and striking piece of jewelry.

Many people in the arts came to Henry Steig's shops. Michael Steig remembers that Ella Fitzgerald and Elizabeth Taylor were among the celebrities who purchased Steig jewelry. He also remembers seeing Edward G. Robinson in the Provincetown shop.

In 1963, Steig closed his shop on Lexington Avenue. He and his wife moved permanently to Provincetown. He ran the shop at 200 Commercial Skeet for nine more years.

"My father's work continued to develop in the nineteen sixties," says Michael Steig. "By this time he was working almost exclusively in 14-karat gold. For the first time he began to hove cost pieces made, a process he had resisted up to that time because he had been reluctant to relinquish complete control over the construction of each piece. He did find a company to cost his pieces that he felt he could trust. He was pleased with the results and continued to explore the possibilities of costing. He also mode some very delicate pieces out of square gold wire at this time."

In Provincetown, Steig pursued his many interests. "In the sixties, my father became most active as a pointer of abstract and semiabstract oils. His work was exhibited at the Provincetown Art Association and the Provincetown Group Gallery," says Michael Steig. "One of his best paintings was done in 1972, when he was already suffering the symptoms of what turned out to be spinal cancer. He was based on a slide he took of Beachy Head, in Sussex, when he and my mother visited during my research year in England."

Henry Steig was o member of a group of recorder players. He was also on avid chess player. Mischa Richter recalls that when Steig became interested in astronomy, not only did he build his own telescope, he also ground the glass for the lens.

In 1970, Steig wrote a manuscript on jewelry making called "The New Jewelry Handbook." It was never published because he and the publisher could not agree on the content. "They were not pleased because it did not cover elementary essentials, which was not his intention," says his son.

Henry Steig sold the use of his Provincetown shop and his designs to Chicago jeweler Jon Dee in 1972.

On February 2, 1973, he died of spinal cancer in Hyannis, Massachusetts.

Of all the careers that Henry Steig successfully pursued in his lifetime, his career as a jeweler was the one he remained at the longest. He leaves behind the legacy of his modern jewelry, a focus for the artistic energies of an exceptional and multitalented man.

Catherine Siracusa and Sidney Levitt write and illustrate children's books. They live in New York and collect jewelry of the '40s and '50s.

Sources

"The Eight Performing Steigs: Artists All," Newsweek, May 14, 1945

"New Writers: Henry Steig," Publishers Weekly, June 21, 1941

Steig, Henry. Send Me Down. New York: Alfred A. Knopf, 1941

"Variety Is Spice" (photograph of Henry Steig pendant), March - April 1953

Letters from William Steig, May 1991 - September 1991

Letters from Michael Steig, June 1991 - December 1991

Telephone conversation with Mischa Richter, August 1991

Telephone conversation with Sylvia Roth, November 1991

Telephone conversation with Michael Steig, January 1992

You assume all responsibility and risk for the use of the safety resources available on or through this web page. The International Gem Society LLC does not assume any liability for the materials, information and opinions provided on, or available through, this web page. No advice or information provided by this website shall create any warranty. Reliance on such advice, information or the content of this web page is solely at your own risk, including without limitation any safety guidelines, resources or precautions, or any other information related to safety that may be available on or through this web page. The International Gem Society LLC disclaims any liability for injury, death or damages resulting from the use thereof.

The All-In-One Jewelry Making Solution At Your Fingertips

When you join the Ganoksin community, you get the tools you need to take your work to the next level.

Trusted Jewelry Making Information & Techniques

Sign up to receive the latest articles, techniques, and inspirations with our free newsletter.