Exhibition in Print: Metalsmiths Win The West

9 Minute Read

Our "notice" calling all metalsmiths guilty of western influences to turn in photographs of their work may have led some notorious and "wanted" characters to flee the limelight, but many bravely complied. This "exhibition in print," based on western themes, is published in celebration of the 1989 conference of the Society of North American Goldsmiths in San Antonio, Texas.

Limited because of space, the selections for publication, nonetheless, represent a wide variety of techniques and subjects. Some entries were as down-to-earth as a pair of Tony Lama boots or the chicken feet left on the plate from the Colonel's Last Supper, a contribution of Jim Cotter; others were influenced by desert plants and resources. The West was also interpreted in symbols like the ancient petroglyphs carved on cliff walls and by sculpture expressing the severe majesty of the landscape.

From the beginning, the theme seemed suitable. Who can deny that the West was won by metal and metalsmiths? There were gunsmiths, and the farriers who kept horses in shoes. The horses were spurred into action and urged to charge by brass bugles. Belt buckles and buttons held the cavalry together. A cowboy without horse gear, a harmonica, a branding iron was a worthless critter; so was a chuck wagon without tin plates and coffee pot. Without barbed wire, the range wars would never have been fought and Billy the Kid might have died peacefully in his iron bed. It was the Gold Rush that helped to pen the trail to California, as well as copper and silver mines along the way. Rails allowed homesteaders to migrate faster and put the James Boys in business. Picture a sheriff without his star, Louis L'Amour without his bolo, and Hollywood without all of these indispensable props.

To the cowboy as subject, James Robson added the cow in the landscape. For an artist living in western Canada, Robson points out, "It is impossible to ignore the ever present 'landscape paintings.' The strength of this tradition is perhaps . . .due to the relatively late settling and cultivation of the land." In this country of open spaces, Robson's cows stand out in high relief. One occupies the middle of a road that disappears into infinity; another pushed to the end of a fence. But in Well, Maybe One More Cow, a bovine creature, like the bull thundering through Wall Street in a well-known TV commercial, has invaded the "stock market." This cow is content to stand in the shade of a tall office building hopefully waiting to be discovered.

The longhorn as icon was given pendant form by a West Texan, Jeanne Sturdevant. After spending "fourteen years in Yankee Territory", she returned to Texas. She landed as she tells it, "in the midst of contemporary longhorn cattle raising in the Blacklands," in the northeastern part of the state. The Legend of a Longhorn, is for her, a symbol of her Texas heritage.

A symbol of a different kind produced William Strickland's Old Faithful: a Souvenir Thermometer. His choice of this subject is traced to early travels which he recalls in these words:

Western motifs have intrigued me since my youth, when my family and I crossed the country repeatedly on old Route 66. The mysterious wide open spaces, the pervading sense of history, and the grandeur of natural monuments could only be dwarfed in my mind by the ever present souvenir stands (See the live gila monster) and the plethora of gas stations, each promising to be the last of hundred of miles. In my work I have tried to capture the essence of those roadside attractions, small monuments in metal to the "Crazy Ed's Last Chance Gas, Discount Fireworks, and Souvenirs" of the old West.

The humor of reducing Old Faithful, that logo of reliability, to the scenic background for a thermometer is matched by Michael Croft's spiky adaptation of a prickly pear cactus as cutter/knife. Constructed from steel and painted wood, the object, like its prototype, when viewed as a hands on experience is enough to make Rambo wince.

Another menace to hikers along western trails has been decently put to rest by Betsy Crump. Funeral Rattle #4 preserves a rattler's tail in a reliquary of gleaming copper, mother-of-pearl and glass walls, neatly curtained with lace. Commenting on this memento mori, the artist says, "By using the rattlesnake rattle, I compare our own fear but reverence for snakes with similar feelings toward death."

Among the Hopi after the summer snake dance ends, the wriggling reptilian bundles are taken to the foot of the mesa and then released to carry the Indian's request for rain to the Supernaturals. Snakes of mirrored chrome, their serrated bodies wound with colored wire and beads, are among the southwestern Indian motifs crafted by Jill Elizabeth. Her koshare dancer pinpoints the intensity and action of the participants in the ceremonials held in the pueblo plazas.

The pictoglaphs and petroglyphs left on the walls of Pre-Columbian rock shelters of New Mexico and Arizona have supplied symbolic imagery for modern metalsmiths. Combining metals designs with a collage of old coins, bones, ivory, vertebrae, found objects and talismans, Susan Silver Brown constructs sculpture as "wearable art." To Brown, a spiral symbolizes the cosmos; a feather suggests spiritual flight; while a lizard becomes "the representative of man's chameleon like and ever changing nature." In the tradition of the shaman/artist, Brown does not consider her jewelry as just something "with which to adorn the body," but she relates it "to man's fate and destiny."

Terri Lee Foltz Fox is another metalsmith drawn to "the mystery and mythology of the primitive arts." Working with married metals—sterling, copper, nickel and brass—she recognizes the dichotomy that exists between controlled technological skills and that "magnetism and spirit" found in Indian and African arts. Similar contrasts are present in Fox's juxtaposition of simplified forms with surfaces covered by a complex patterning. A pendant in the form of a loom illustrates the harmonious resolution of these tensions. The loom is a tightly constructed frame, a utilitarian object that has changed little in structure for millennia. In contrast, the design attached to the loom answers a need for intricate and repetitive patterns that Fox believes can induce "visual meditation and contemplation."

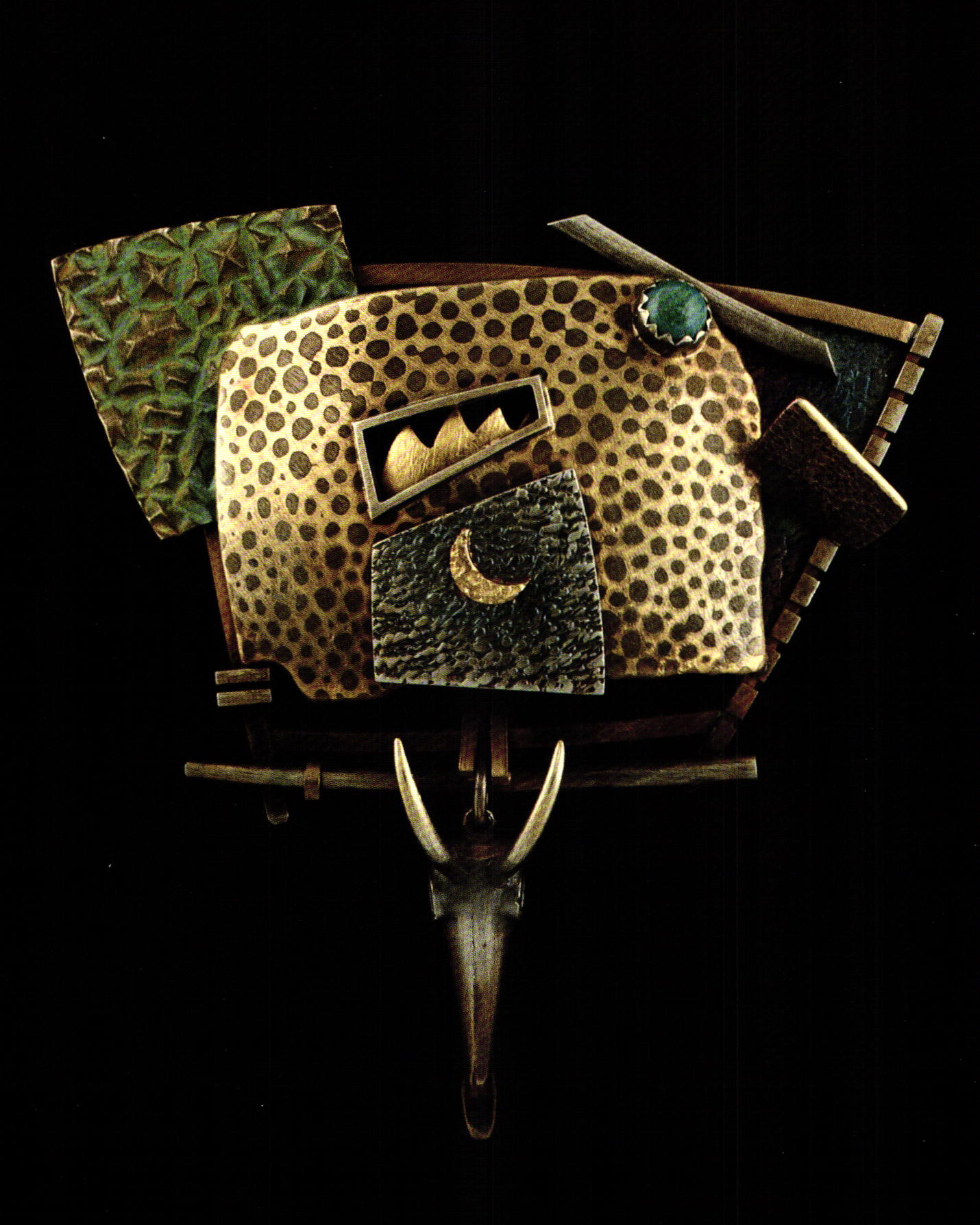

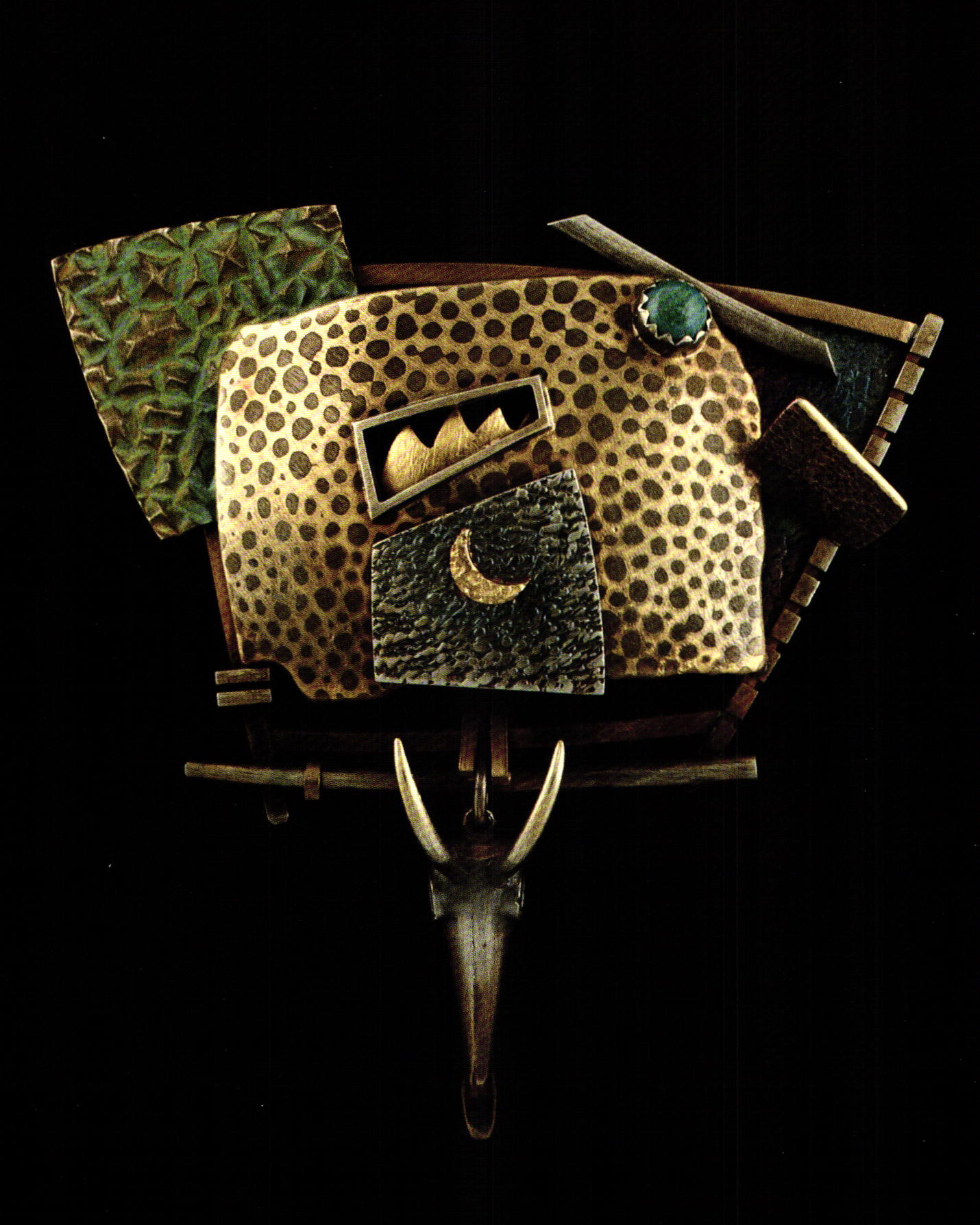

Robert McCall's Interior Landscape also conveys a contemplative mood. The format is an inverted triangle. Smaller triangles have frequently appeared in McCall's designs with the impact of projectiles shooting across a surface to heighten tensions. In this, the effect is quiescent and dreamlike. Forming the vortex of the triangle, there is a polished metallic cow's skull, with curving horns repeated in the tips of a crescent moon, which rides above on a patch of sky. A field of textured metal suggests the imagery of cow's hide. It supports a framing device that discloses a series of points, gleaming like a prairie fire or the serrations of mountain peaks. There is a temptation to read symbolic meanings in McCall's metal statements, but without benefit of the artist's own words, it is safest to brand this brooch as a powerful and provocative abstraction.

A buckle crafted by Donna Matles displays an abstract interpretation of banks of clouds rising over the deep cuts of arroyos and rock beds. The wood, bone and silver used are all materials found in the western landscape.

The earth in a broader sense is the subject of William Baran-Mickle's metal sculpture. He writes about the influence of the land on his art, explaining:

Much of my work draws upon the rich variety of images available to me over the roughly 25 years that I spent in the Western United States. From the dry southwest (born in Texas) . . .all the way past Oregon and to the Northwest Coast, the monumental landscapes of cliffs, ocean, mesas, canyons, valleys and mountains have inhabited my subconscious whenever I would design a brooch, sculptural vessel or my current pieces of sculpture . . . I rarely utilize a specific place or land formation in a work. Rather, I try to get at my feeling for a place or land formation or focal point that has a sparkle to it more as a reminder of the life, energy or spirit of the place and of Native People . . .than for true or literal depiction. It is always my hope that this "essence" can picked up by viewers to re-affirm their own connections to the natural world.

In reading the statements written by the metalsmiths about their art, it became apparent that high standards of craftsmanship and technical facility acknowledged as imperatives, but most of them were also searching for communication at a different level of perception with the viewer or wearer of jewelry. This awareness, of the essence lying beneath the surface, forged a link between the exhibitors and those western Americans, the Navajo. The Navajo word for beauty is hózhó, but this is not beauty in the generally accepted meaning of the term. To the Navajo metalsmiths, it is not enough to speak only of the finished work of art; the process by which the work was created must be taken into account as well as the artist who made it, the use to which it will be put upon completion, and who will use it.

For the Navajo perspective, the piece is merely the vehicle whereby beauty, hózhó, is transmitted from an artist who is himself or herself in a state of beauty, to a recipient or audience, who will in some measure be brought into a state of beauty through viewing, wearing, or appreciating what the artist has done and made.

Notes

- Southwest Indian Silver from the Doneghy Collection, ed. Louise Lincoln (Austin: University of Texas Press. 1982), p. 40

Elizabeth Skidmore Sasser is a Professor of Architecture at Texas Tech University, Lubbock and a contributing editor to Metalsmith.

You assume all responsibility and risk for the use of the safety resources available on or through this web page. The International Gem Society LLC does not assume any liability for the materials, information and opinions provided on, or available through, this web page. No advice or information provided by this website shall create any warranty. Reliance on such advice, information or the content of this web page is solely at your own risk, including without limitation any safety guidelines, resources or precautions, or any other information related to safety that may be available on or through this web page. The International Gem Society LLC disclaims any liability for injury, death or damages resulting from the use thereof.

Related Articles

Jewellers’ Objective Attitude Towards Designing

Hiroko Sato Pijanowski – Artistic Research Into Spiritual Expression

Metalsmith ’85 Spring: Exhibition Reviews

Hermann Jünger: German Goldsmith

The All-In-One Jewelry Making Solution At Your Fingertips

When you join the Ganoksin community, you get the tools you need to take your work to the next level.

Trusted Jewelry Making Information & Techniques

Sign up to receive the latest articles, techniques, and inspirations with our free newsletter.