A Conversation with Michael Rowe

11 Minute Read

Michael Rowe uses functional containers as a base from which to explore formal studies of space, form and balance, which are enhanced by his expressive use of patination. His holloware gains strength from the fact that he is not distracted by the lure of sculpture or nonfunctional vessels.

Last fall, Rowe's work was the subject of an exhibition at Contemporary Applied Arts in London and we asked Deborah Norton to interview him concerning the progress of his work since the publication of his influential book, The Colouring, Bronzing and Patination of Metals in 1982.

Deborah Norton: In an article I wrote recently for Metalsmith I suggested that metalsmiths might avoid making trite pieces if they asked themselves why they are making something before they begin. Now, looking at your work, which I find very exciting, I wonder, why do you make the things that you do?

Michael Rowe: I have always been intrigued with the process of how form is generated. But in order to explain more fully, let me go back to the beginning. As a student at Royal College of Art (MA 1972), I was creating silver objects that were miniature metaphorical worlds of architecture furniture and even landscapes. Essentially I was making containers that were referring to containers on other scales, like architecture I was fascinated with illusions, especially Chinese perspective—where the viewer is the center of the world—and oblique and isometric projection. And I was interested in space—how to organize and reorganize it. But by 1976 I realized that my pieces were getting too complicated. The miniature scale didn't seem to be working. I needed to radically reassess what I was doing. The first thing I did was to clear away all references to other scales. I also threw out the metaphorical references and the extraneous embellishments, such as complicated chasing that I had been using. I went to work on cubic boxes. The challenge was to create the boxes that spoke only of themselves, yet had the ambiguities and illusions of the earlier pieces without the metaphors. I continued my exploration of projection and perspective, concentrating on the articulation of form by perception.

Deborah Norton: What exactly do you mean by that?

Michael Rowe: How things appear in the space they occupy I was very much influenced by Cubism and, like the Cubists, I was interested in the object/viewer relationship and the idea of multi-viewpoints. When you look at a cube you see angles other than 90 degrees, depending on where you are standing. In order to make this sort of perception a reality, I distorted angles, extended sides and, added planes so that, for example a viewer could stand in front of one of my boxes and set the lid (in a fixed position, not hinged) both opened and closed and from several angles at once. Then I wanted to see if I could do something similar with other forms so I went on to hemispherical bowls.

Deborah Norton: Why hemisperical bowls?

Michael Rowe: I wanted to pick up on my holloware heritage. And I was interested in working with archetypal forms, trying to get as pure as possible, thus the cube and not a rectangle; spheres and not ovals. Like in holloware, I explored the concept of a main form to which secondary forms—spouts and handles—are added. I experimented with having the secondary forms compete with the main form, and I found that the secondary forms took over. The symmetry would shift from the axis of the main bowl to a new axis that took into account the secondary forms. But I realized that the bowl was not the right vehicle for looking at secondary forms, so, in 1983, I went on to cylinders. Cylinders were perfect because I could break the generation of form into facets, thus creating curves out of straight lines.

Deborah Norton: Why was this important?

Michael Rowe: It's hard to put into words. But intuitively I felt I had the seed to generate a multiplicity of forms. The poet Rilke, Rodin's secretary, said that he was always looking for a seed from which to craft his vision. For me the seed was the straight line from which I could make curves. It was the correct vocabulary for me.

Deborah Norton: Do you mean from a design standpoint or the actual construction?

Michael Rowe: Both, but mostly design.

Deborah Norton: One thing that intrigues me about your cylindrical forms is the imagery and even humor that I find in them. For instance, your Condition For Ornament No. 9 at first struck me as a humanoid figure with two breasts and a duck's tail. Then I looked at it from the other side and the tail became a vertical mouth chomping on a football with wings in back. Then, after I had studied it for a while, I decided no, it couldn't be. This is a serious study of form and balance. Was the imagery intentional?

Michael Rowe: Yes, that ambiguity is exactly what I'm striving for. I intentionally chose secondary forms that had metaphorical meanings that could be read equivocally. I wanted to confound the viewer's expectations. After a period of no imagery—creating very pure objects without reference to anything but themselves—l began loosening up with the cylinders. They were a real breakthrough for me and very surprising. I had been working in a Modernist tradition and now, suddenly, I was taking on ornamentation. Because that's what the secondary forms were. They weren't spouts or lids, they were ornaments.

Deborah Norton: So that helps to explain the title for your latest series, Conditions For Ornament.

Michael Rowe: Yes. While working on this series I asked myself what exactly it is that I am doing. The answer was, creating conditions for ornament where "conditions" takes on both meanings, "atmosphere" and "making the rules."

Deborah Norton: I especially liked your piece that was meant to sit on the corner of a table and from the back you have to peek between the walls to see the cylinder. What was the idea behind the corner placement?

Michael Rowe: I was thinking about how things are oriented in a particular way on surfaces. In Conditions For Ornament #6 three of the same forms placed in three different ways behave differently depending on where they are placed. This made me think about the randomness of placing things in contrast to fixed placement. With this corner piece I let the tabletop dictate its position.

Deborah Norton: Let's talk about patination and surface decoration for a minute. Ever since the publication of your book (The Colouring, Bronzing and Patination of Metals by M. Rowe and R. Hughes, 1982) you have become reknown for your innovative use of patination. What attracted you to patination in the first place?

Michael Rowe: I had been experimenting with it since I was a student. This was quite frowned upon in school as everything was supposed to be polished. But I wanted a sense of mass in my pieces and you can't get that with a polished surface—either you look right through it or your eye is reflected off it. I also wanted color. So I began collecting recipes from old text books. Later when I was teaching at Camberwell School of Art and Craft in 1979, there was research money available to explore patination further. Richard Hughes, one of my colleagues, and I tested over 1,000 recipes and eventually wrote the book.

Deborah Norton: Why in this Conditions For Ornament series did you abandon patination and use a tin finish instead?

Michael Rowe: Several reasons. There's a toughness to the tin finish that these forms needed. Patination would have been too soft. And I like the fact that tin carries a reference to tin ware, which is modest but beautiful. Also, because it's a molten metal I was able to create an interesting globular texture. Plus it gives a bright surface without being reflective

Deborah Norton: So you could have a bright surface yet still have a sense of mass?

Michael Rowe: That's right.

Deborah Norton: It is obvious that the finish is very important to your work. Do you ever design a piece around it?

Michael Rowe: Not exactly. But I always think about the finish while I'm designing. I never complete a piece and then think, what shall I do with the surface. The finish says something about the nature of the object. It makes a real contribution to the piece.

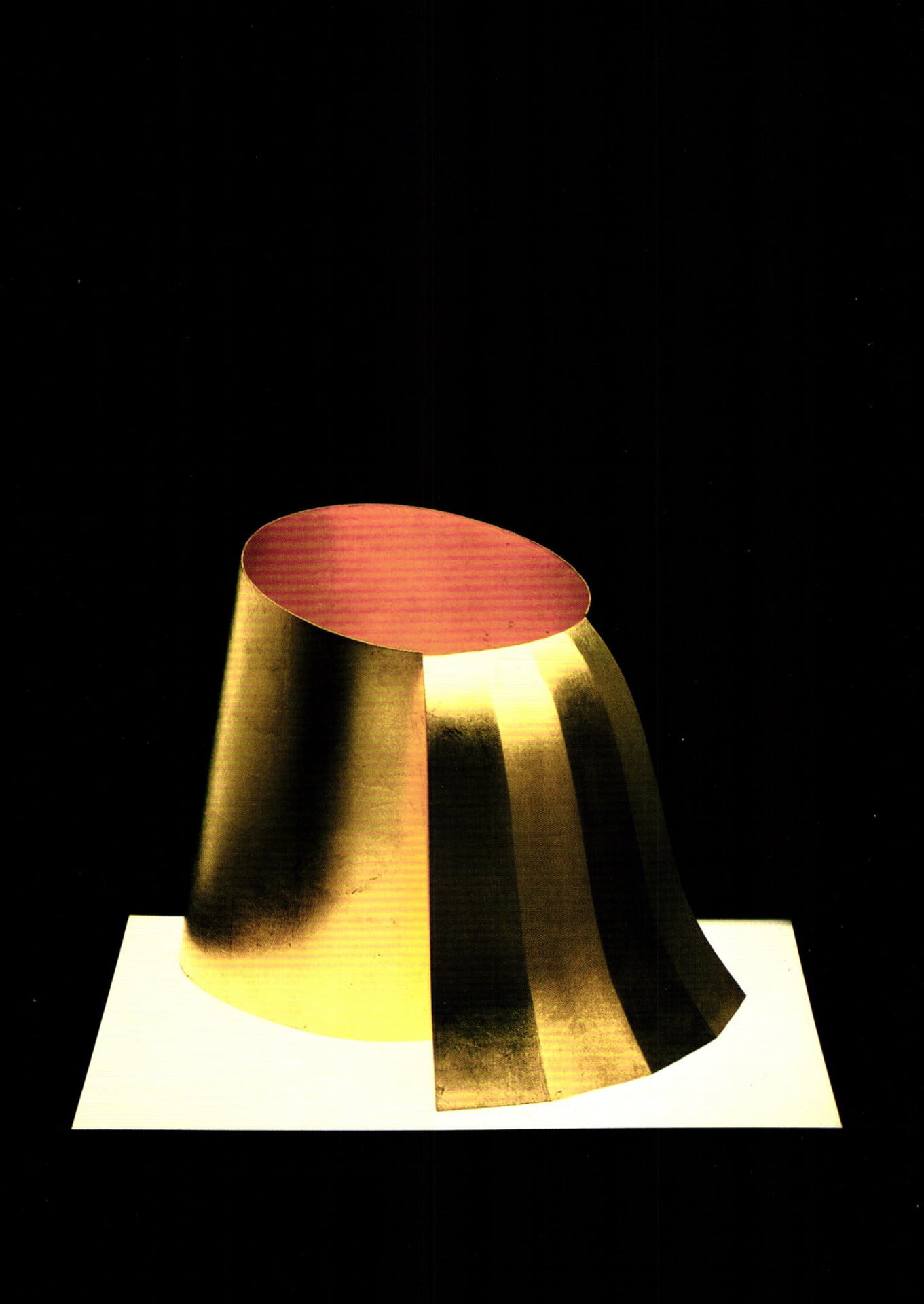

In 1986 I made a pair of objects that explored contrasting finishes. The structures of the two pieces were quite similar but one was meant for the kitchen and had a tin finish that gave it a stark, metallic, hard-wearing quality. The other was a living room piece finished with gold leaf and had a completely opposite effect. It was glowing and delicate and appeared to be floating like a leaf. The contrast between the two was tremendous.

Deborah Norton: Your work seems so well thought out and controlled. In a piece such as Conditions For Ornament No. 8, every element works perfectly; it seems like you could only have achieved this if the whole thing was planned our before you started. Is anything left to chance?

Michael Rowe: Oh yes, my work isn't nearly as calculated and scientific as it looks. I start with a drawing and then create a model with cardboard and bits of metal. But when it comes to actually making the piece I work very intuitively, letting my eyes tell me what's going on.

Deborah Norton: Have you ever considered using CAD/CAM for designing and manufacturing your pieces.

Michael Rowe: I haven't. Because my designs come from working directly with the materials, I wouldn't want to lose the first hand experience.

Deborah Norton: Another thing that impresses me about your work is how well you handle the functional aspect. Although your containers are very sculptural, they never become nonfunctional. Yet, having the constraint of functionalism doesn't seem to limit you at all. If anything, it makes your work stronger.

Michael Rowe: I feel that if the intention is to make a functional vessel but you get led away to something so that it's no longer functional, then you have to tackle the issues of sculpture. But what usually happens is the vessel becomes a crutch for bad sculpture. The philosopher Kant said, "Concepts without intuitions are blind; intuitions without concepts are lame." To me that means that no matter how strong your concept, if you don't have strong intuitions about how to use them then they're just theory. And vice versa, if your work is only intuitive without concepts, it lacks structure and rigor.

Deborah Norton: While we're on the subject of philosopher's quotes, I have read that another one of your favorite quotes is Heidegger's, "Things gather world." What does this mean to you?

Michael Rowe: It opens up the whole thing about what objects can be. According to Heidegger, objects are a part of their environment and to some extent are influenced by the context in which they are placed. The reverse is also true as this is an active relationship. When thinking about vessels we should be aware of their potential to contribute to the genius loci of architectural spaces.

Deborah Norton: In talking to you and reading other things that you've said, all your influences seem to come from fine art—Cubism, Modernism, Cezanne, Giotto—and philosophers. Are you ever influenced by crafts?

Michael Rowe: No. I really don't look to craft at all, although I'm interested in the history of silver and metalwork. But I'm rarely inspired by contemporary craft. It's usually sloppy, second-rate sculpture. Deborah Norton: All your cylindrical forms are made of sheet metal. Would you ever consider using other techniques?

Michael Rowe: I love working in sheet metal . . . the precision you get. But it's very slow. Recently, in a workshop, I tried doing some castings. I liked the speed with which you can create, and I plan to explore castings more fully. I think that trying to maintain a spontaneous look in metal is a tremendous challenge. It's certainly easier to do with castings than with sheet metal. Perhaps this will be another seed from which to generate forms.

Deborah Norton is a contributing editor to Metalsmith, living in London.

You assume all responsibility and risk for the use of the safety resources available on or through this web page. The International Gem Society LLC does not assume any liability for the materials, information and opinions provided on, or available through, this web page. No advice or information provided by this website shall create any warranty. Reliance on such advice, information or the content of this web page is solely at your own risk, including without limitation any safety guidelines, resources or precautions, or any other information related to safety that may be available on or through this web page. The International Gem Society LLC disclaims any liability for injury, death or damages resulting from the use thereof.

The All-In-One Jewelry Making Solution At Your Fingertips

When you join the Ganoksin community, you get the tools you need to take your work to the next level.

Trusted Jewelry Making Information & Techniques

Sign up to receive the latest articles, techniques, and inspirations with our free newsletter.