A Conversation with John Marshall

29 Minute Read

John Marshall was born in Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania in 1936. After serving in the Armed Forces and doing construction work, Marshall began his college study in 1958 with one year of business administration. By 1960 his attention had been redirected to silversmithing and design. He studied at the Cleveland Institute of Art between 1960 and 1965 and then went on to teach and pursue graduate work from 1965 to 1967 at the School of Art, Syracuse University, New York. He remained there as an instructor and then as assistant professor until 1970, when he joined the faculty at the University of Washington in Seattle.

The following conversation is taken from a series of interviews, which took place in December 1990 and February 1991, in Seattle and at Marshall's home and studio in Edmonds, Washington, with Patterson Sims, curator of modern art and associate director for art and exhibitions at the Seattle Art Museum.

Patterson Sims (PS): What personal factors have shaped your professional life?

John Marshall (JM): I started out in a family in which the arts played a very small role. My father supported us as a truck driver. In the Pittsburgh school district, a program was coordinated with the Carnegie Museum of Art to provide small scholarships for high school students to attend Saturday classes at the Museum. I was the student selected to represent my high school and this opportunity, together with my mother's encouragement, inspired me to become an artist. However, I never thought art would become a profession because I enjoyed it too much. After high school, I went into the service to take advantage of the GI Bill and then worked in construction in order to fund my studies. During my first year at Grove City College, while majoring in business administration, I was able to take an elective art class. It was probably the best thing that ever happened to me, because it was there that an art teacher convinced me that I should consider art as a career.

For one year I took evening classes at Carnegie Tech in Pittsburgh and worked construction jobs during the day in preparation for an art career. Next, it was my good fortune to enroll at the Cleveland Institute of Art and study design with goldsmith John Paul Miller. He taught a sophomore design class and had an intuitive sense for a student's talent. He told me that the way I was doing my work and with my patience I should think about metalwork and holloware. After I finished my first two years at Cleveland, I could have gone into painting, advertising or industrial design. I realized I couldn't be a painter; I love form too much. I enjoy working three dimensionally to make space move and form happen.

At the Institute I tried clay, I tried wood, I tried many materials just to see how I felt about them. It bothered me that a lot of the materials didn't have a sense of being stable. I couldn't get over the fact that glass and ceramics were so fragile: drop them and they're gone. Under the influence of John Paul Miller, I turned to metal. Metal gave me all the things I really enjoyed. I loved to planish, to take all day and hammer out all those marks left by the raising of the silver, all the while thinking about the other pieces I wanted to make. The material met my temperament.

I then enrolled in an evening class in silversmithing and jewelry with the other instructor, Fred Miller (otherwise no relation), and found that it was something that I felt at home with. Fred Miller is a real craftsman, possessed of a dedication that makes him unable to accept anything less than the best. He was a mentor par excellence.

Initially, after graduating from Cleveland, I really wasn't interested in teaching, and I couldn't afford to go to graduate school. I was about to accept a position at General Motors as a model designer when I received a 5th-year scholarship at Cleveland to work toward a BFA, and I was offered a position to teach high school students at a Saturday class. At one of these classes, the wife of Laurence Schmeckebeir (former director of Cleveland, and then dean at Syracuse University) asked me if I would be interested in coming down to talk to her husband. I went down, had an interview with him, Schmeckebeir asked me to join the staff at Syracuse, and I did.

Having only a BFA, I felt somewhat inadequate to head a Program, so I really got involved with processes in order to become a better teacher, working both with jewelry and holloware as well as enamels. My first commissions were mostly small jewelry pieces, and I worked up a series of enamels using drawing (basse taille). I went into granulation; worked with gold and enameling; used repetition and variation as I played with form; and I made jewelry, holloware and sculpture. I had a special attraction to juxtaposing materials, techniques and processes al Syracuse. I learned to "draw" by coating copper with a resist and then scratching through to eat away the surface with acid. I'd then carefully lay down an underglaze into those lines and fire clear coats of color on top to retain the drawing. This process is very much like the attitude found in printmaking. I developed an ability to shift from functional work to sculpture, to make my functional work more sculptural. At Syracuse I became more involved with explaining and comparing my work both within and outside my field. I was able to receive my MFA while teaching there through my work with Schmeckebeir. He felt that my ability to work the metals was of the caliber to receive the MFA, but my communication skills needed work. He gave me special writing and public speaking assignments, literally throwing me into the very lion's den of public debates and lectures. He arranged for my Master's Show to be at Syracuse House in New York, and this was my second opportunity to benefit from the inspiration of an intuitive teacher.

At the end of five years, our program had moved from temporary quarters in the basement of a dormitory to permanent facilities. And I found that my work grew as well as my awareness of other art. I became both more involved with other attitudes of art and more critical of my own art. I really appreciated the school's support of their art faculty. They took every opportunity to see that I got commissions. The chapel asked me to do a chalice cup/baptismal that would work with all denominations; I came up with a gold chased bowl with a ceramic dish made by a local ceramicist, again mixing techniques and materials. Also, I designed a chancellor's bowl with a ladle and a chancellor's medallion.

PS: Once you got to Washington State your work opened up even more.

JM: I got a great job at the University of Washington. I came there for the professional opportunities. But I was also influenced by the amount of open space - and the beautiful color. The Northwest has definitely affected my work. I became more aware of different types of form because of the severe terrain, and very aware of the subtle and clear colors.

PS: We speak of the Northwest as being an area of the United States that has a strong craft tradition and a strong craft community. Have you found that to be the case?

JM: I already knew of the strong craft tradition because of the National Ceramic shows at the Everson Museum at Syracuse. I was aware of the Seattle-based ceramic artists Howard Kottler, Patti Warashina and Robert Sperry, for example. I find that the craft field has a great deal to offer here. The people have a definite integrity in their work. The relationship that they have with their materials seems to be more natural. With my own work, I find the attitudes of form and space feel more comfortable here than when working back East; my work has grown in scale and risk-taking.

PS: Drawing plays a big role in your work, which makes me think of the Northwest-associated artists Morris Graves and Mark Tobey.

JM: Drawing has played a major part in my work, both in its way of problem solving and communicating to myself as well as to my clients. Without my drawing skills I possibly could not have been able to get the exciting commissions I have had to work on. Many people in the crafts downplay the drawing, feeling that working into the material is where the expression should start. But as I tell my own students, you can experience many more ideas on paper in the time it takes to make one piece in metal. I am influenced by drawings I see in the Northwest, but drawings played an important role back as far as Cleveland where drawing was a major part of the curriculum. At Syracuse, while developing the enameling process, I used drawing. A good example of this is a piece owned by Everson Museum in the permanent collection called "Who Killed Cock Robin?" where I used a drawing of a dead bird. It was a strange thing. I had made a series of pieces about the whole cycle of life. I was working on this piece at about four o'clock in the morning, and I felt a sudden need to have a dead bird to work from. I walked outside and it was kind of scary, at my feet I found a dead bird.

I constantly relate my drawing and my two-dimensional skill of engraving and chasing to three-dimensional form. I fault people who don't draw. But then I also fault people who can only draw and then make the piece exactly like the drawing. The drawing is a point of departure, but a craftsman should always listen to the metal as he works it. I am fascinated by what can happen to a surface that brings out another aspect of drawing. Lines, whether they're put down with a pencil, a chasing tool or an engraving tool, play with the eye and allow the eye to dart in and out. What's especially nice with metal is that you can engrave a line into a piece of metal and then light makes it. Line moves across a contour and complements the line on the form. At times I think that when physically I can no longer work with the tools of the silversmith, I will be able to express myself by drawing.

Another reason why drawing is important for the student and the beginning craftsman is that it is one of the best means to get commissions. When you first start out, people just don't come up to you and say I'd like you to do a coffee set. You have to show drawings and use your sketches to let people know what you'll be making for them. You have to commence with drawings that communicate what you will be doing. Plus drawing is the greatest wav for you to solve problems for yourself. You can go through many ideas and throw them away or select some over others - this is all part of the drawing process.

PS: Commissions play a central role in your art; can you talk about the process of commissions and discuss a few specific people and projects?

JM: I made a decision when I was at Syracuse that I would not take commissions where I would have to compromise my identity. However, I have been fortunate in that in most cases, I'm really excited about commissions, and I'll really try to do the best job I can to please clients. I found I must have commissions in order to support a family - let's be honest, teaching is not the most lucrative means to buy tools, build a studio and support a family. I have had great commissions and have met beautiful people in the process. What you're looking for is a client with an understanding of the arts, someone who doesn't ask about what the piece is going to be worth in 10 years. In most cases, I am not too excited about getting involved with a gallery, because a gallery separates me from the client. What I really enjoy about commissions are the people. Commissions come about either because of a show where I'll make a contact with someone or when someone sees my work at someone else's home; one person leads to another.

PS: Can you be specific about some of the people you have worked with and some of the projects you've done for them?

JM: For instance I've made many silver bowls for a range of clients from the Seattle art collector Anne Gould Hauberg - who has commissioned several pieces over the years - to a memorial to honor the Airborne Rangers of the Korean War. The bowl I made for the Rangers has a 36-inch disk, which is engraved with all their campaigns and names, and sits on a polished basalt stone. For another Seattle collector, Dr. Darryl Rogers, who wanted a sculptural, but functional, coffee set, I made a stacking coffee/tea set. The teapot is on the bottom; the sugar bowl comes next. The coffee pot next and then at the very top is the pouring sugar bowl. The lids drop right into the sugar bowl. I incorporated the Northwest terrain by using chasing to engrave the landscape. I always try to merge the sculptural and the functional to get double use. Another commission was a six-gallon punch bowl and 36 cups to go with it for Charles Mayer, a collector in Sandusky, Ohio for whom I've done a number of pieces.

PS: And when you have a project with 36 cups, do you have any assistants?

JM: Every once in a while I've hired people, but I don't have them work in my studio. For the cups, I actually had three of my graduate students help. They just raised them and then I did all the chasing and the repoussé. For the basalt stone, I have a friend that works with stone and I give him a very carefully scaled and detailed drawing. He works up the stone first and then I work the silver to fit that stone. If I feel that the stone is not working, I'll take it back to him and we'll make little adjustments.

Another interesting Seattle commission was done for Mark Bloome. I worked up a set of candleholders that functioned both on the table and as sconces. After I finished that commission he asked me if I was interested in flatware. I wasn't sure that I wanted to get caught up in something that would take up a lot to time and duplication. But I said the only way that I might consider it would be to do eight different place settings. All the bowls and the fork tines and blades are the same, but the handles are all different. It's not the usual set of knives, forks and spoons. They actually play with the settings, all the pieces are positioned on one side or maybe the knife will be above the plate. They have a series of sketches of all the different ways in which they have laid out the silver.

I have also done projects for public buildings, especially churches here in the Seattle area. I did a chalice in copper and silver for a church in Bellevue. The bowl can be taken out and used separately or placed into the holder and held by the base. Initially, a church in Ballard just wanted me to do a cross. It is about 11-feet high and made of teak with a metal crown of thorns that floats in front of the crossmember. It is supported from stainless steel wires and the congregation walks beneath it. But as I was underway, they got me involved with the rest of the church. I ended up designing their altar, the candleholders and the baptismal bowl. I have also worked for the Edmonds Methodist Church designing pieces for their chapel and main sanctuary. The piece in the main sanctuary was in memory of two sons who died at different times. I designed a piece using anodized titanium abstractly where the forms are separated at the base by an arch representing the church, and they come together at the top symbolizing their coming together again in death. I find myself working more conceptually now in my pieces and being less involved with the craft, feeling confident that my hands will perform as a craftsman.

But my most remarkable patron came into my life when I displayed my work in the faculty exhibition at the Henry Art Gallery of the University of Washington in 1979. The great collector Patrick Lannan was in Seattle to look at glass, came to the show, saw a piece there and purchased it. Lannan was also interested in a large punch bowl that was in the show that I could not sell because it was for another client. He responded by commissioning me to do another, even larger punch bowl. Because of its scale, I employed hydraulics to push the form out and then went back into it with chasing and repoussé to give the details. The first time we sat down, he said he enjoyed my work and wanted to buy it. He asked if there was any room for negotiation? And I said no. From then on, we never talked about money once I set a price. Patrick then said he'd like me to do something that would be more sculptural and asked me what I wanted to do. I described a design for three related pieces; I laid out just what I wanted to do, how long I needed, etc. I was paid by the month. I was building a studio then, and it was just the right thing all around. When he asked how long I wanted to work on the pieces, I said, "About two years." And he said, "What scale?" to which I replied, "Something around six feet." Patrick arranged for the silver to be sent to my home. The finished pieces were shipped to his place in West Palm Beach, Florida. Eventually, he designated a Marshall Room in his residence.

At the same time that I was preparing for the Lannan commission, I was invited to give a lecture and workshop in Alaska. I was very impressed by the glacier and its effect on the space. This became my concept for the first three pieces I did for Lannan. The first piece, called Glacier, uses copper to represent the cooling of the earth; the silver represents the actual ice over the earth and the light from below showing through acrylic represents the freeze. The second piece, Freeze, depicts a total freeze from ice to chill to ice and uses chasing and repoussé work on the sheet with the wood base. The third piece, Thaw shows the thaw, and the meltdown of the ice. Patrick's commission allowed me to consider the idea of working silver in six-foot sheets, which was almost unheard of at that time. He then invited me to work for another two years during which time I completed two other sculptures: Aurora and Landscape. On the Lannan pieces I would spend a whole day on a little area that might be only 5 inches by 5 inches, just producing patterns with a surface that was 5 feet long. While I was working on these pieces, Lannan would sometimes fly out and we would have an opportunity to talk about the work in progress. He died prior to the completion of Landscape, which I titled in his memory. After completing Landscape, l visited his home and for the first time saw all of the pieces displayed together in the Marshall Room. Lannan was very direct and strong-willed in both his manner and conversation; every artist should be so fortunate as to have this kind of experience with a client.

PS: You went back to making functional pieces after the sculpture you created for Lannan. Will you always have a dichotomy in your work between the functional and the sculptural? Or will you conclude that you want to be a sculptor, and not take any more functional commissions?

JM: Basically I am a worker. I was given a talent and I enjoy using it. I enjoy meeting the challenge of function, whereas too many craftspersons are not being true to the material or to themselves. Function is an integral part of each service piece I do - all parts must work within the design and nor in conflict with the sculptural movements. A teapot that does not pour correctly compromises the sculptural intent of the design. In too many cases, where the craftsman or the artist has attempted to give a sculptural attitude to functional pieces, the sculptural part makes it function less effectively. But also, behind it all, is the sculptor who wants to get out.

PS: When I look at your work, I'm more impressed by the functional pieces than I am by the sculptural pieces. Your sculptural pieces seem to be too frozen by conventions of the 1950s and 60s, whereas your functional pieces seem to be able to transcend tradition. Is that because you've devoted so much more of your energy to functional pieces? Or, in making a differentiation between these two aspects of your work, would it be possible to s:ry that your functional work is better?

JM: I think my functional work is better; after all, this is where the majority of my time has been placed. I've solved many problems of functional work and added something to that field. Sculpture, though, I find is a must, so I can express myself and fantasize or just spontaneously find new forms.

PS: Who has influenced you and your work the most, the artists who work with functions or the sculptors?

JM: I have a very hard time isolating specific people who have influenced me. It could be someone who makes functional works or a sculptor. Among my colleagues in Seattle, I admire the ceramic sculptors Robert Sperry, Howard Kottler (sadly no longer alive) and Patti Warashina. In Patti's work, for instance, I like the way she draws on her surface, you read a two-dimensional surface on a three-dimensional form.

I really enjoy Alexander Calder's sense of line, how he makes form out of a very flat pattern. As you walk around his pieces, you lose the third dimension because they are made of flat sheets of metal. Calder moved back and forth easily from being a maker of useful objects and sculptures. Above all, I find myself very drawn to Henry Moore's work. His forms engage an energy that actually seems to grow from the inside out. I admire his sense of surface and texture.

Two people who have influenced me are John Paul Miller, who taught my eyes to see and Fred Miller, who made me aware of what my hands can do, and, at the present time, my colleague, Mary Hu, who produces form through lines of wire. I am also influenced by the forms of Henning Koppel - his quiet functional form. I admire Claus Bury for the exciting dimension found in his pieces and his ability to change the scale of his work, and AJ Paley for his aggressive, linear composition.

PS: Finally, if you were to define yourself briefly, would you say you were a metalsmith, a sculptor, a maker of functional works or a craftsman?

JM: The whole idea of answering that question irritates me, because I don't know. You are asking me to commit myself; I don't want to. At this point, i want to be left alone. It's taken me a long time to establish this intelligence, skill and talent. I have had an opportunity to do something here, and whether you like it or whether it goes into a history book, I could care less. I want to work. Every time I come into my studio, I realize what I don't know. The more you learn, the more critical you become, the more precious time becomes. I've got to make the best use of every moment. For someone to ask me whether I want to be a sculptor, jeweler, or metalsmith is, at this point, foolish. I think I have enough of a reputation that I can do what the hell I want to do. I've proven that I am a craftsman, I've proven that I can be a sculptor and I've proven that I can deal with color and line.

PS: In terms of influence, do you try to travel out of Seattle and see other people's work?

JM: Yes, I feel that it's very important for artists to expose themselves to other art. It's necessary that I get to places like New York at least every few months for a three- or four-day visit. The first time I experienced New York, I said to myself, I have to do this as many times as I can. To go through the Museum of Modern Art and see a sculpture by Lipschitz or a painting by Picasso is crucial to my growth as an artist.

PS: Just as you look back to others for ideas and inspiration, you have developed a major reputation as a teacher. What are your feelings about teaching and your students themselves?

JM: Teaching means a lot to me. Many professors often say they wish they could retire, constantly talk about how the students drain their time and take them away from their work. They should quit, because they're probably not good for the student either. I must say that the teachers that made all the difference to me in my growth as an artist were also very active in their art. It is a very hard role to play, breaking yourself away from your work and getting involved in someone else's thoughts. But I enjoy the students because they're always challenging me and keeping me sharp. I'll never forget the first time I got a leave. (I went through the whole time at Syracuse without a leave.) It was in Seattle when I took my first quarter off, full pay, took myself and squirreled away, and I didn't like it so much. Don't get me wrong; through every leave I have taken, my work has become stronger, which has made me a stronger teacher. But it's a narrow line between my time and the students' time. I have a reputation of being kind of a bear if people interrupt me. I have laid out my life carefully and my family's been very tolerant of me. If I don't get that time, I'm miserable and everyone around me is miserable because I'm miserable. I have certain days that I work in my studio. But when i go to teach, I tell my students, I'm yours. I will crawl through your ideas to find out how I can help you. I don't want to make a little Marshall out of you, but it is my mission to help you understand who you are. Identity is the big thing. To mold a person properly is another creative attempt. They do their thing, you come over there and throw a couple of words at them or be a sounding board. That's all you need to do for some. For others, you have to physically nurture them by taking the pencil or hammer from their hand and demonstrate. Also, you must support them by feeding them, processing information and making the space they work in more effective. And to others you need to say, hey, this isn't for you.

PS: If you could bring any living artist to talk to your students at the University of Washington, who would it be?

JM: I would like to have Claus Bury come to talk with my students and give insight into his work. He is a person who works geometric illusions in his small jewelry pieces as well as site-specific work in large scale. He has a tremendous sense of color as well as form and does a find job of marrying the two. He also uses drawing in his work to prepare and explore.

PS: In recent years, the world has been fascinated by the idea of a MacArthur Grant, a grant that for five years gives it recipient sufficient income to pursue what he or she wants to. If such a thing happened to you, what would you do?

JM: I've thought about it and actually know someone who received one. To be able to work solely as an artist for five uninterrupted years seems unbelievably exhilarating. I would take silver through a whole series of functional pieces - coffee sets, trays, candleholders - expressed in almost a sculptural way, and then progress through these pieces to establish a sense of what that metal can do in esthetic terms, creating tabletop and floor pieces. It would be a tremendous opportunity, especially at this time when my hand and head feel like one.

PS: Do you sometimes get frustrated by how obdurate a material silver is?

JM: Metal has a quality to it that you can build upon, you can have a lot of time with it or work very spontaneously. I've done some pieces I've been satisfied with in 15 minutes and others that have taken six months. Silver is just fluid enough and just rigid enough for me. Silver has an identity that is very friendly to everything around it, it brings everything into it, the reflections of color go in and come back to you.

Also, it's a precious material that is economically accessible again. When I was working on the Lannan pieces, silver rose to $30-40 an ounce; people would come into my studio and all they could talk about was how much such a large amount of silver cost. It was slightly inhibiting when I was engraving or cutting into the silver. But now, it's great because my students can work with silver long before I could have done so as a student. Please remember that when I say that silver is my medium, I am also referring to all those other materials that I've put into a relationship with the silver: titanium, basalt, acrylic, gold and a few others.

PS: Do you have anything you would like to say directly to metalsmiths that we haven't covered?

JM: The one thing that is needed right now in our field is communication. I think we're doing a very shallow job of this, because when I read articles I'm reading the same thing. The whole idea of technique is overplayed. We had a whole period when all people wanted to talk about was what granulation or reticulation or mokume-gane was and how it was accomplished.

We are underrating ourselves when we talk metalsmith-to-metalsmith all the time. Within art history programs, how much is said about metal? Most people don't know about it, and when they do, it's usually just about technique. I think that people need to know more about why artists do what they do and what they are trying to say. For example, I like to hear from artists like Richard Mawdsley, Helen Shirk, Chunghi Choo, Heikki Seppä, Brent Kingston, Stanley Lechtzin, Bob Ebendorf…what are they actually doing and why.

PS: You make the field sound like it is in crisis.

JM: The silver field is really struggling today. The industry in England and the United States is very traditional, producing the same patterns over and over again. The industry is not really keeping up. They continue to push those yellow designs, when they could be making an art form for the table that would keep up with the exciting things that are happening in architecture as well as interiors.

In the United States we leave taken metal further than anywhere else. The Scandinavians are very clean and functional with their design. The English are tremendous craftsmen, particularly with their floral decorative things. Germans are making pieces that say things with a cold machinelike form. But Americans are taking metal more into an art form than anyone else.

PS: Do you also have dreams and aspirations for the material?

JM: Yes, I'd really like to see metal make a statement like canvas does. It could do a better job because we don't have to build an illusion. Color and alloying are making a big difference. Silver can move off the table and be more of an esthetic statement.

PS: Because silver is what we call a precious material, people often ignore the esthetic choices that have gone into making it, marvel at the craft of its production and either make functional use of it or only respond to the luxurious appeal of the finished product. They deal with it in a much more summary fashion than they might works of art made in less intrinsically interesting materials. So much metal is made for its pure decorative value and ostentatious adornment that it's difficult to acknowledge its complex web of spiritual, emotional and esthetic ideas.

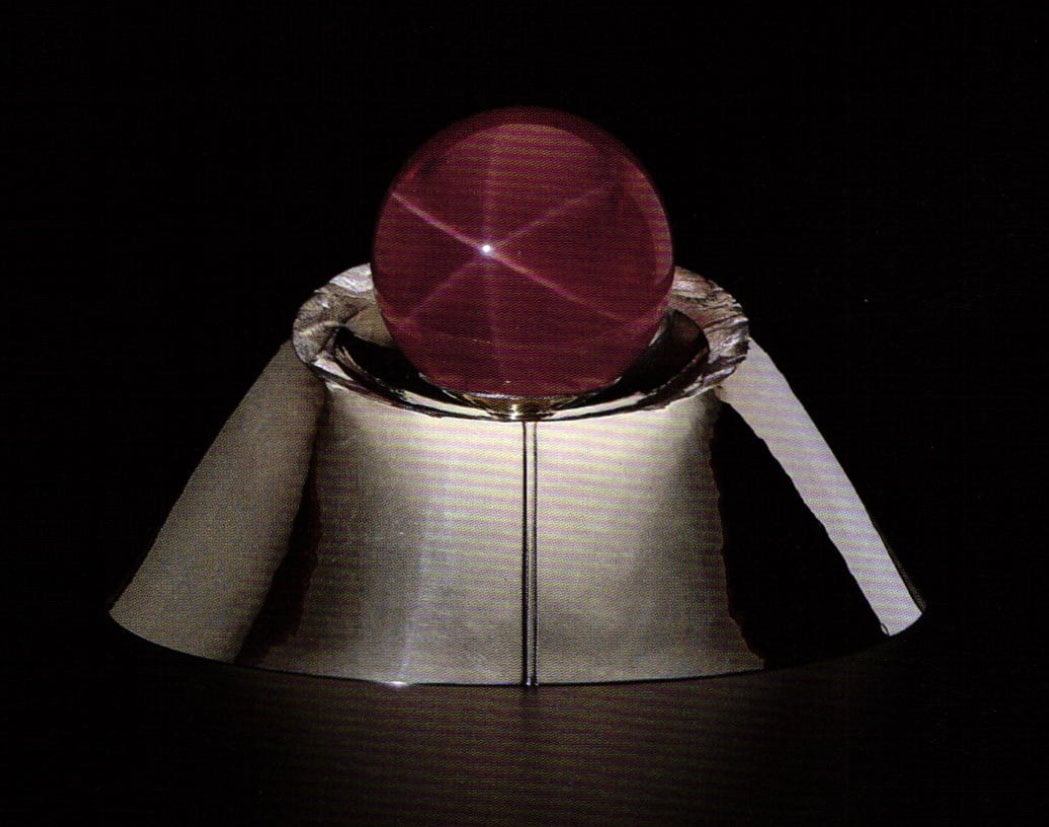

JM: At this stage, I see the material of silver differently. I'm just beginning to use it to play with the idea of how reflect into the world and how the world reflects into us and into my pieces. The reflections that fall upon silver and the other materials I use produce spheres of illumination. This ongoing circular motion invites you in. It's a path. Now if I used a material that wasn't silver or I used a bigger scale, if I was a "sculptor" not a "metalsmith," you would be asking me what that line and path is. In sonic of my new pieces I see two people who are inside working their way to the outside, enveloped by the whole sense of the world. Metal allows you to imagine what you want to see in it because of its reflection and luminosity. Light dematerializes pieces and simultaneously substantiates them.

My feelings toward this metal, when I think about it, have not changed much. Just when I feel a complete understanding of it within my grasp, I find something new that makes me wonder if it's still just the beginning. It's exciting and I still feel the challenge.

John Marshall's work will be the subject of a retrospective exhibition at the National Ornamental Metal Museum in Memphis from September 15 to November 10, 1991. The exhibition will be accompanied by a 12-page, full-color catalog with 27 images, available from the museum, 374 West California St., Memphis, TN 38106 for $6.50, including postage.

You assume all responsibility and risk for the use of the safety resources available on or through this web page. The International Gem Society LLC does not assume any liability for the materials, information and opinions provided on, or available through, this web page. No advice or information provided by this website shall create any warranty. Reliance on such advice, information or the content of this web page is solely at your own risk, including without limitation any safety guidelines, resources or precautions, or any other information related to safety that may be available on or through this web page. The International Gem Society LLC disclaims any liability for injury, death or damages resulting from the use thereof.

The All-In-One Jewelry Making Solution At Your Fingertips

When you join the Ganoksin community, you get the tools you need to take your work to the next level.

Trusted Jewelry Making Information & Techniques

Sign up to receive the latest articles, techniques, and inspirations with our free newsletter.