American Modernist Jewelry 1940-1960

4 Minute Read

Recently, collectors have discovered a body of silver jewelry, eclectic in scope—by turns serious and whimsical—creative, original and quintessentially modern. It has been termed "50s jewelry," as if it embodied—in miniature—the aesthetics of that period. Yet, this casual association is misleading. While the 1950s did witness the widespread diffusion of this jewelry, its important features were formed as jewelers sought to ally themselves with the "project of modernism." This process was initiated in the 1930s and 1940s. It culminates—in the following decade—in the triumph of what can be called modernist jewelry as an official style. . . .

The origin of "contemporary jewelry" has been traced to 1936 when Sam Kramer began to make jewelry influenced by Surrealism. Kramer drew on that part of the modern experiment which devolved around fantasy and the absurd, automatic writing, the unconscious, chance and parody. A superb writer, he recollects the accidental discovery of his favorite technique:

One time, working by trial and error in the fireplace (a convenient place for such experiments) I was trying to evolve a new casting technique. When silver is molten it flares, and dances like mercury. Suddenly a sputtering bubble of liquid silver squirmed out of the ingot-mold and cooled in an odd shape on the hearth. This piece, this accident of spilled metal, vaguely resembled a duck's head. And it started me thinking about how silver and gold could be blasted by flame until it ran almost fluid, then controlled, built-upon and fused again until it resulted in small sculptures with the texture and all the flamelike movement of this kind of primal ordeal by fire.

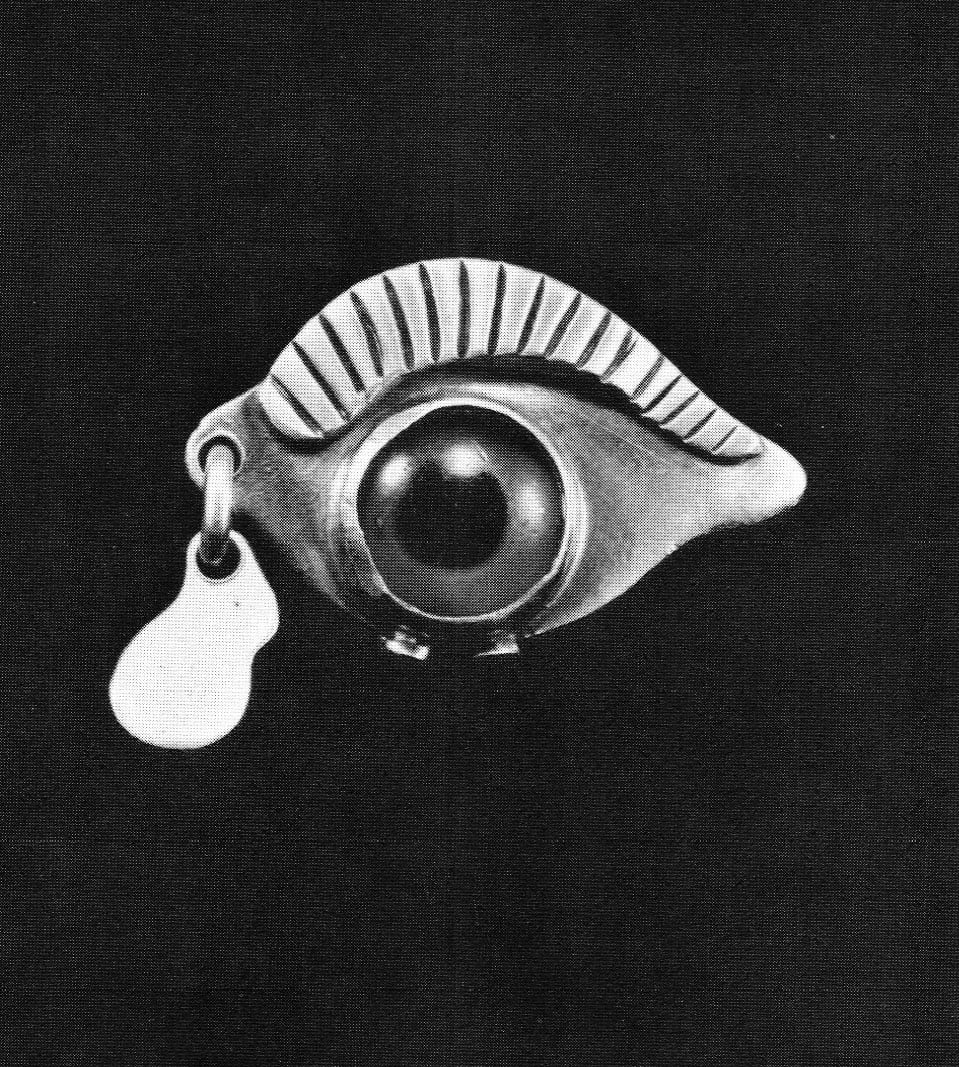

The rapid heating and fusing of metal, the very urgency of the technique is akin to action painting, the loaded brush, work emerging at the edge of control. This unstable method would produce nothing resembling the cool technical hand of De Patta. The typical Kramer piece is suffused with fantasy and humor (and, of course, eyes). Meant to shock and provoke, his disquieting images recall Harold Rosenberg's idea of an "anxious object."

There is, also, a propensity in modernism for severing symbol from context and for transposing meaning. Introduced by Braque and Picasso, the method of collage/montage operated by displacing: "a certain number of elements from works, objects, pre-existing messages and to integrate them in a new creation in order to produce an original totality manifesting ruptures of diverse sorts." Kramer, who advertised his gem trade in the back pages of Craft Horizons, advocates just such a purposeful inversion:

Changes from the traditional have here an astonishing and somewhat ironic logic. The old stones, rigid in cut and shape, are being used now in an exciting new context, while the stones new in cut, shape and kind tend to fit into the older setting with the gem dominating.

Identification as art became the principal doctrine of modernist jewelry. It was espoused with all the fervor of an article of faith. Phrases like "solutions to design problems," and "achieving equilibrium of design elements," appropriated from the criticism of nonobjective art, crop up repeatedly.

Moreover, modernist jewelers advanced a claim for the appellation "artist." They saw their work as fine art writ small—the miniature. De Patta considered her works to be "wearable miniature sculptures and mobiles." Others, as well, refer to sculpture or modern art. Even their shops become "miniature museums."

Modernist jewelers appear to have formed a conscious and voluntary affiliation with the fine arts. Behind the scenes, however, institutional forces were at work, serving to encourage this tendency. These were subsidy, patronage and professionalism. . . .

At the close of the 1950s, modernist jewelry had become an official style. Taken up by the university and the museum, patronized by the luxury market, complete with publications, associations, traveling exhibitions, juries, the modernist jeweler became the jeweler in the gray flannel suit. The vanguard had been displaced by the professional; experimentalism by "accepted" innovation.

In 1964, the jury for the St. Paul Gallery Exhibition would find the majority of entries: "repetitious or imitative, or contrived with the obvious effort to be different."; Modernist jewelry was now a product, and, as one modern critic of the fine arts has noted, once a produce has been named, other examples are churned out, as if to order.

Modernist jewelry is not merely jewelry or even art. Each piece serves as a signpost or marker in the symbolic landscape traversed by modernism. Its range includes the cerebral association of the Bauhaus and the stream of consciousness of the Dada/Surrealist. As art and artifact, modernist jewelry redefined jewelry and illustrates the forces that produced the dynamic of modernism.

Notes

- Morton, Phillip, Contemporary Jewelry: A Studio Handbook (Holt Rinehart Winston: New York), 1970, p. 36.

- Kramer, Sam. Design Quarterly, no. 45-46 (1959), p. 56.

- Group Mu, eds. Collages (Union Generale: Paris), 1979, pp. 13-14

- Kramer, Sam. "Gems in New Contexts," Craft Horizons, vol. 12, no. 5 (Sept./Oct. 1952), p. 33.

- Uchida, Yashiko, "Margaret De Patta," The Jewelry of Margaret De Patta (The Oakland Museum: Oakland, CA), p. 12.

- "Arts and Ends." Craft Horizons, vol. 10, no. 1 (Spring 1950), p. 22.

- Morton, Phillip. Contemporary Jewelry: A Studio Handbook (Holt Rinehart Winston: New York), 1970, p. 49.

This excerpt from the "Structure and Ornament" exhibition catalog is reprinted here with permission of the author and Fifty-50.

You assume all responsibility and risk for the use of the safety resources available on or through this web page. The International Gem Society LLC does not assume any liability for the materials, information and opinions provided on, or available through, this web page. No advice or information provided by this website shall create any warranty. Reliance on such advice, information or the content of this web page is solely at your own risk, including without limitation any safety guidelines, resources or precautions, or any other information related to safety that may be available on or through this web page. The International Gem Society LLC disclaims any liability for injury, death or damages resulting from the use thereof.

The All-In-One Jewelry Making Solution At Your Fingertips

When you join the Ganoksin community, you get the tools you need to take your work to the next level.

Trusted Jewelry Making Information & Techniques

Sign up to receive the latest articles, techniques, and inspirations with our free newsletter.