Recent Sightings: Craft Identity

5 Minute Read

This article series from Metalsmith Magazine is named "Recent Sightings" where Bruce Metcalf talks about art, craftsmanship, design, the artists, and techniques. For this 1994 Fall issue, he talks about craft Identity.

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

I recently visited the jewelry/metals program at SUNY New Paltz, where Jamie Bennett and Myra Mimlitsch-Gray teach. It's one of the premier jewelry/metals programs in the country, on both the graduate and the undergraduate levels. It's also one of the places where the future of craft education is being formulated. Like many teachers, Bennett has wrestled with the prospect of teaching a craft in an art school. Since it's not obvious what can legitimately be called art, and the ideologies that define and justify art change, teachers like Jamie must constantly re-answer the question: how does craft belong in an art school?

In the seventies, the emphasis was usually placed on personal expression. Theoretically, the student learned what she had to express before the art enterprise truly began. Thus, education in art consisted partly of locating and clarifying the student's sensibilities and values, usually in relation to her personal experience. The teacher helped the student discover what she valued most, which became the subject of her expression. Students made expressive craft.

The problem with this approach, at least as applied in a craft education, eventually became clear. If personal expression is the first priority, where does that leave the traditional craft forms? Should jewelry students be making sculpture and presenting performances, all in the name of self-expression? What does a teacher do when a student refuses to make objects at all, but instead binds himself to a pillar with duct tape, insisting that het making art? (This actually happened in one of my classes.) When students refuse to make craft in a craft program, the institutional justification for having the program disappears. Why not just call it all sculpture, and dispense with all those bothersome tools? In fact, the merger of craft programs into sculpture has occurred in several schools, with very mixed results.

To solve that dilemma, Bennett now asks his students to restrict themselves to craft as context, or as subject matter. That is to say, students at New Paltz are encouraged to work within a familiar craft context, like jewelry or hollowware, or to take craft as the subject of a discourse. So, even if a student is interested in installation art, that installation has to be about craft in a meaningful way. In turn, the institution can recognize the products from Jamie's classes as being essentially craft, not sculpture. The students, who generally think that art is still better than plain old craft, get the best of both worlds. Craft about craft is conceptual, and every student in the nineties knows that the primary marker of art-ness is that it must be conceptual.

The strategy of making objects about craft is Postmodern. It's closely linked to certain kinds of art from the past decade, including that of Hans Haake, Barbara Kruger, and Gordon Matta-Clark. This art is about representation, not in the narrow sense of art being a picture of something else, but of art corresponding to the social structures of the wider culture. Of course, craft that addresses culture demands a broad knowledge, not just about technique and history, but also the social and political implications of whatever craft is being studied. And of course, students have to know art theory, too. Once it was sufficient to make a well-crafted and well-designed object, but no longer. The new craft demands a critical study of culture, and the new generation of students is far more sophisticated than any before.

The idea of making craft about craft is spreading, and probably will characterize craft education in the next decade. This attitude guides a number of professors who came of age in the eighties. However, not everything is peaceful in this picture. The most potent conflict seems to come from the confusion about what comes first in the educational agenda: craft-as-expression, or craft-as-subject-matter.

If a student looks to the history of craft, and then is required to choose some aspect of it for her subject matter, what is the basis for the choice? How does she know what piece of history and which ideological spin to select? The range of possibilities is huge, and a student needs a way to navigate through them. At this point, traditional approaches to expression become useful again. Where students were once asked to find something to express, now students are asked to find something to address. But the problem of personal engagement remains. If the student can clarify, her values, she is better able to select those aspects of craft and culture that are resonant and meaningful to her. Otherwise, she has no personal stake in the subject matter.

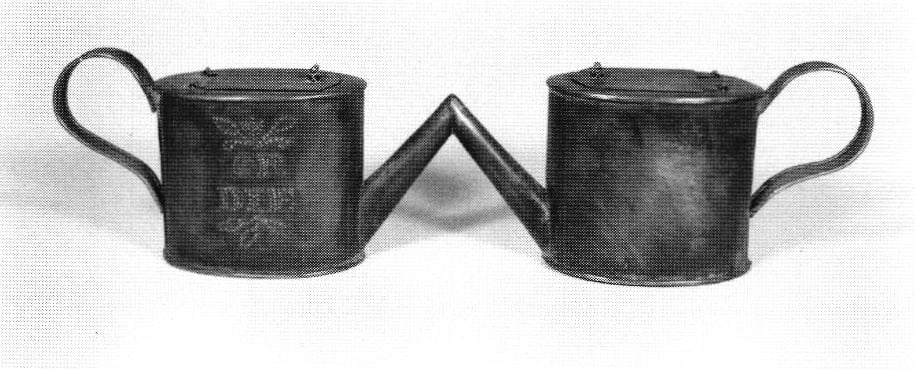

Although some students at New Paltz solved the quandary brilliantly, like Jonathan Wahl with his wonderfully twisted, homoerotic tin coffeepots, a sizable minority of the students were thoroughly confused. Responding to suggestions that they look to jewelry or metalsmithing for a subject, some students made choices without conviction. Some of this confusion was the inevitable condition of students trying to say too much at once, and thus not knowing quite what to say at all. But for others, it seemed that their chosen subject matter had nothing to do with their talents or interests. Their personal values weren't engaged. The result was lackluster work, and a lot of hot air expended in trying to defend it.

There may be no universal solution to this problem. It's probably better to teach with a clear ideological position - that craft is obligated to address its own history and context - than to have the "anything goes" attitude that typified so much dismal education in the sixties. Unluckily, ideology inflicts casualties. Some students may not be mature enough to make the choices demanded of them. On the other hand, neither Bennett nor Mimlitsch-Gray are making the choices for their students, which lesser teachers might do. At least, students at New Paltz are given the chance to succeed or to fail under their own power. That's one sign of a good education that won't change.

Bruce Metcalf works, writes, and teaches occasionally in Philadelphia.

You assume all responsibility and risk for the use of the safety resources available on or through this web page. The International Gem Society LLC does not assume any liability for the materials, information and opinions provided on, or available through, this web page. No advice or information provided by this website shall create any warranty. Reliance on such advice, information or the content of this web page is solely at your own risk, including without limitation any safety guidelines, resources or precautions, or any other information related to safety that may be available on or through this web page. The International Gem Society LLC disclaims any liability for injury, death or damages resulting from the use thereof.

The All-In-One Jewelry Making Solution At Your Fingertips

When you join the Ganoksin community, you get the tools you need to take your work to the next level.

Trusted Jewelry Making Information & Techniques

Sign up to receive the latest articles, techniques, and inspirations with our free newsletter.