Forging Modernist

21 Minute Read

"The only work that counts," she added with her quick smile, "is, of course, that which affords the opportunity for complete and satisfying self-expression." Such was the record of one interviewer of Janet Payne Bowles recalling her early days in Boston still searching for "the work in which I could put all my energy and enthusiasm." Payne Bowles's lifelong artistic and intellectual quest too her from an initial interest in music to writing, psychology, and handicrafts. When she married and left her Indianapolis home in 1895 she quickly connected with the nation's leading circles of progressive art and thought, first in Boston and, from 1902 to 1912, in New York. It was not until approaching middle age, however, when she separated from her husband and returned to Indianapolis that she quickly connected with the nation's leading circles of progressive art and thought, first in Boston and, form 1902 to 1912, in New York. It was not until approaching middle age, however, when she separated from her husband and returned to Indianapolis that she found her opportunity and then embarked on an important and successful career that united the pursuit and practice of art, ideas, metalwork and jewelry with teaching about them. Nearly all of Payne Bowles's surviving work was inherited by her children who donated it to the Indianapolis Museum of Arts between 1968 and 1981. Remarkable, courageous, and wholly original, her legacy bridges the Arts and Crafts movement's interest in revitalizing culture through reforms in taste, design, and production methods and the modern art movement's preoccupation with spirituality and the forceful expression of inner feeling and emotion.

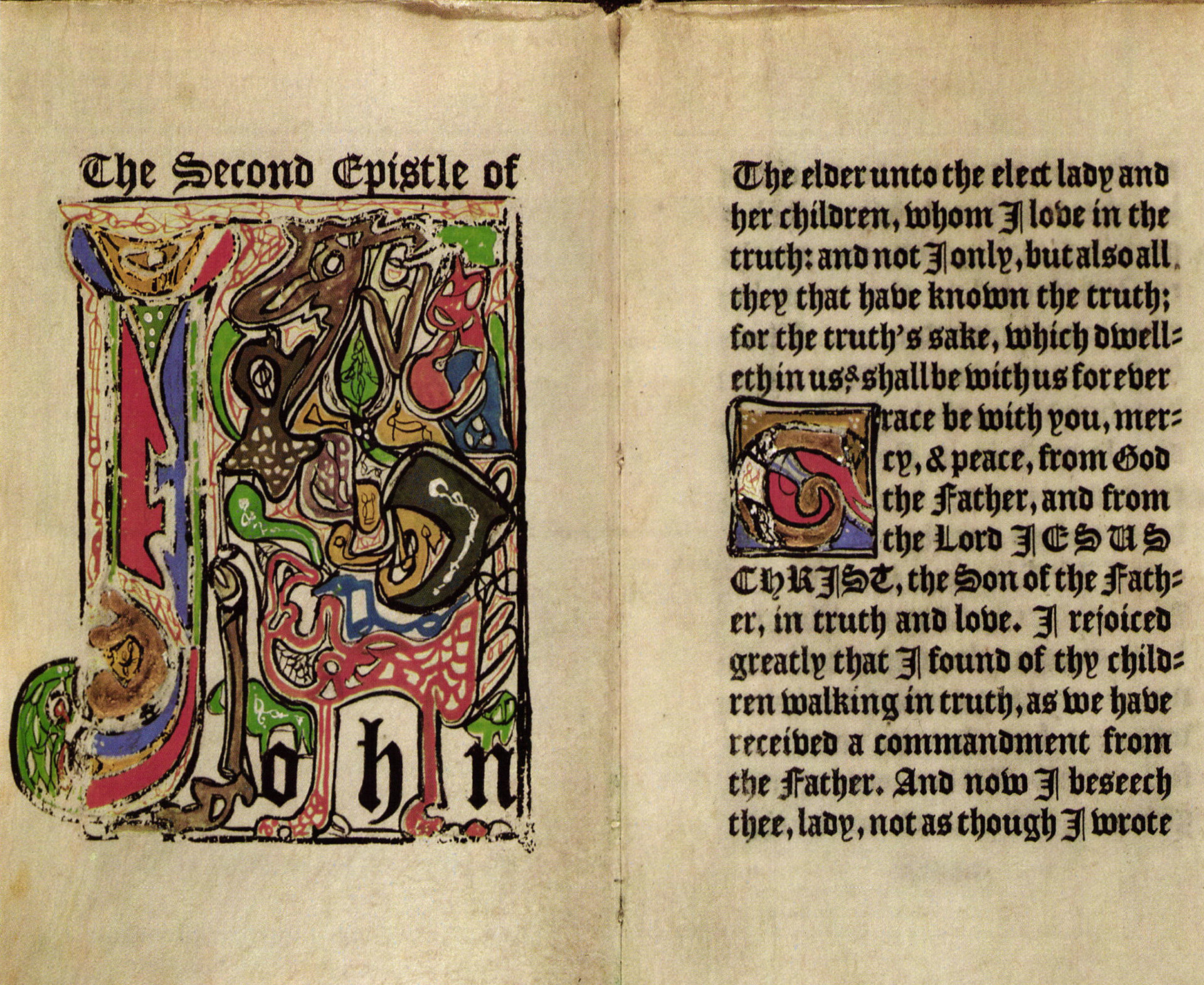

Payne Bowles's first known art work was illuminating initials designed by Bruce Rogers for R. B. Gruelle's, Notes: Critical & Biographical, a book about the paintings owned by William T. Walters, (father of the founder of Baltimore's Walters Art Gallery, Henry Walters,) which was printed in 1895 by Joseph Moore Bowles, then well-known as the publisher of the lavish arts periodical Modern Art and who also was wed to Payne Bowles the same year. The earliest Payne Bowles works to survive are illuminations in four copies of The Second Epistle of John published by her husband in 1901. The configuration of scroll interlacing and animal forms in Payne Bowles's illuminations (Fig. 1) were in the then current Celtic revival style and carry on the spirit of pages decorated by Bruce Rogers who had been working with Joseph Bowles from about 1890. The flat-patterned interweaving, the tendril and vermicular shapes with knob ends, the contrast of solids and voids, and the wide-eyed creatures in these illuminations reappeared later in Payne Bowles's early jewelry (Fig. 2). Payne Bowles continued making illuminations for her husband until at least 1910, but by then she was giving most of her time to making jewelry.

With the acquisition of Modern Art by the Boston lithographers Louis Prang & Company in 1895, the Bowleses began married life in Boston where Joseph Bowles carried on as editor of the magazine and to which Payne Bowles was an occasional contributor of book reviews. The young couple became active participants in local arts events. Joseph Bowles exhibited at Boston's historic April 1897 arts and crafts exhibition, an exhibition that led to the establishment of the city's Society of Arts and Crafts the same year. Upon becoming a member of the Society of Arts and Crafts, he was a lender to its 1899 exhibition which displayed not only copies of Modern Art and Payne Bowles's illuminations for Gruelle's Notes, but other books including the landmark first edition of Arthur Wesley Dow's Composition. Both this manual and its author exert a strong influence on the artistic maturation of Payne Bowles.

Payne Bowles was also a lender to the 1899 exhibition with "metal ornaments" made by Chicago metalsmith and jeweler Mary Elaine Hussey. Scant information exists on Hussey and no examples of her work are known, but she may have engendered Payne Bowles's initial interest in making metalwares and jewelry. The catalogue for the inaugural Housewarming Exhibition of Articles in Gold and Silver held in October 1899 at the National Arts Club in New York City stated that Hussey contributed a cast and chased silver belt knuckle and cast and chased silver garter clasps with and without jewelrs. Bowles's earliest known jewelry efforts were also cast.

While Payne Bowles was being stimulated by Boston's emerging arts and crafts movement she was also being awakened intellectually by the lectures in psychology and philosophy she attended given by William James at Radcliffe College. It was on a respite from these classes that she evidently first learned metalsmithing in 1900 or 1901. Over the years she reminisced about her chance acquaintance with a Russian youth making metalwares by hand in a small shop on Boston's waterfront and the agreement the two made to exchange instruction in metalsmithing for lessons in psychology. The immigrant craftsman was probably carrying out the kind of vernacular work Boston's Society of Arts and Crafts was then seeking to revive. In the century's first years, opportunities for learning metalcraft and jewelry outside the factory system were just being introduced; texts for beginning amateurs only became widely available after 1903-4 In a 1942 interview, Payne Bowles recalled her difficulties in acquiring metalcrafting skills: "All skilled craftsmen are jealous of their skills and will not willingly teach you their secrets."

In 1902 the Bowleses began a decade living in and near New York City where Payne Bowles began her career as a metalsmith and jeweler. Underscoring their commitment to progressive ideas, the couple and their two children made an adventurous move in 1906 to Upton Sinclair's ill-gated socialized living experiment at Helicon Hall. This ended abruptly with a disastrous fire in early 1907 and the loss of Payne Bowles's manuscript for her psychological novel Gossamer to Steel. However, when the Bowles family relocated in Manhattan that spring, Payne Bowles set up a jewelry and metal shop for herself where her husband based his newly-founded Forest Press.

Payne Bowles was familiar with the Greek, Roman, and Egyptian collections at the Metropolitan Museum of Art. Published interviews relate her frequent visits there and acquaintance with Sir Caspar Purdon Clarke, the museum's director. In 1908 she evidently had useful guidance from observing the metalcrafter K. Okabe, one of two Japanese craftsmen employed at the museum to clean, repair, and plan for the re-arrangement of the Japanese metal collections.

A silver pendant (Fig. 2) is probably one of the earliest surviving examples of Payne Bowles's jewelry. It was cast just as the Bronze age Celtic jewelry it recalls was cast and its design of animal faces overlooking a lapis lazuli heart is comparable to the ornamental patterns and animal faces that appear in Celtic and early Nordic Art. Moreover, it bears out the assessment Joseph Bowles made of his wife's work in a March 1910 letter to Frederic Allen Whiting, secretary of Boston's Society of Arts and Crafts, that it was "the barbaric sort of design in which she works most naturally."

Payne Bowles acquired sufficient knowledge and experience to achieve important recognition by 1910. Maude Adams, then a widely celebrated actress, commissioned her to make jewelry and metal accessories for her role as Rosalind in Shakespeare's "As you Like It." In addition to buckles, chains and other ornaments the elaborate ensemble included a curtle ax and a spear and was reported to be made of silver set with green onyx stones. Period illustrations reveal the Celtic and Roman influence on Payne Bowles's design and one account noted "the jewelry which Mrs. Bowles designed is …elaborate in detail, yet simple in homogeneous effect."

Also in 1910, Frederic Allen Whiting, published Payne Bowles's article "A Situation in Craft Jewelry" in the Society of Arts & Crafts, Boston's journal, Handicraft, and it appeared soon thereafter in the Jeweler's Circular Weekly. In the essay, Payne Bowles admonished amateurs and cautioned successful professionals on the pitfalls found when competing with commercial jewelry. She also urged craft jewelers to pursue a thorough familiarity with materials and techniques with this advice:

"The knowledge of the chemistry and geology of his material will give him as much psychic power in work as a great sensitive knowledge of design. Its wide knowledge gives him imaginative fuel, and he finds himself trying to produce effects ethereally conceived. This is the spiritual process of enlarging the limitations of his craft."

Reviews of the 1910 annual exhibition of the National Society of Craftsmen (New York) gave favorable mention to Payne Bowles's work, and in the International Studio, J. William Fosdick commented on her carved silver cross set with a cat's eye, observing that her work was "Celtic in spirit" and "carried out in a broad, free spirit which is most commendable." Greco-Roman influences are also apparent in Payne Bowles's jewelry especially pendant chains whose links duplicate Roman examples. In addition to pendant crosses (Fig. 2), examples with Christian symbols include a silver and gold ring with the "Chi-Rho" monogram.

By 1912 Payne Bowles had found the crafts of metal as the world in which she would operate as an artist. When she returned to Indianapolis that Spring she was met with interest and acclaim for her achievements as a metalsmith and jeweler. In October 1912, the Indianapolis News reported that she would conduct classes in metalwork at the John Herron Art Institute (now called the Indianapolis Museum of Art). The same month, the Shortridge Daily Echo reported that Payne Bowles was contemplating teaching an advanced course in art metal. By February 1913 the class had been formed; and in December 1913 the Indianapolis press reported that Payne Bowles was at work on a set of spoons commissioned by the J. Pierpont Morgan estate.

Through her relationship with Sir Caspar Purdon Clarke in New York, Payne Bowles had been introduced to J. Pierpont Morgan, president of the Metropolitan Museum of Art. Morgan, who was an avid collector of ancient jewelry and metalwares, doubtless had some understanding with Payne Bowles that motivated her to commence work for him, and following his death in March 1913, to continue this work for his estate and heirs. Although the Indianapolis press reported Payne Bowles's progress on this work, correspondence, invoices, or other confirming evidence for this commission are unknown. The gold and jewel-inlaid spoons for Morgan mentioned in the Indianapolis press between 1913 and 1920 presumably correspond to those illustrated in a 1924 profile on Payne Bowles in the International Studio, where they were captioned "Gold Spoons Made For J. Pierpont Morgan" (Fig. 3). Close study reveals that all but two of the spoons illustrated in the article survive in the Indianapolis Museum of Art's collection: but they are made of silver and although the ring terminal of one spoon (Fig. 3 bottom, fourth from left) may have originally held a jewel, none is embellished with jewels.

Most of the spoons published in the 1924 profile as having been made for Morgan were probably completed by 1915. In addition to Christian symbols (Fig. 3 top, far right) some of the spoons illustrate Payne Bowles's practice of invoking a mood of spirituality with avian and zoomorphic forms; one spoon has a handle that incorporates what appears to be a figure peering from a window topped by a rooster and a bowl joined to the handle by a head and arms. (Fig. 3 top, third from left). Silhouette is dominant in several spoons (Fig. 3 top, far left; bottom, second from right) and provides the background for an intricate overlay of soldered and fused elements that exhibit the complexity and mystery of the earlier cast zoomorphic motifs. The curls, beads, and snips on one spoon (Fig. 3 bottom, far left). Silhouette is dominant in several spoons (Fig. 3 top, far left; bottom, second from right) and provides the background for an intricate overlay of soldered and fused elements that exhibit the complexity and mystery of the earlier cast zoomorphic motifs. The curls, beads, and snips on one spoon (Fig. 3 bottom, far left), although built up out of molten globs and drips and fused snips and wires rather than being cast, correspond to Payne Bowles's earlier interlaced and vermicular work. However, where Payne Bowles previously constructed form out of interlaced vermiform elements, here she composed in a sequential, additive process that induced what she termed "the creative flow." In a manner typical of her later work, her fabrication methods are a visible part of her expression.

A lead box (Fig. 4, next page), one of the three surviving metal works signed by Payne Bowles, may be the box which earned her a bronze medal at the Panama-Pacific exhibition of 1915. Although its irregular surface of drips and blobs of molten lead is vaguely brain-like and recalls the zoomorphic creatures in Payne Bowles's earlier work, it is not dependent on representative images; subject matter has been dismissed. More abstract forms served her growing interest in exploring self-expression unrestricted by conventionalization and the constraints of traditional metalsmithing practices.

By the late 1910s Payne Bowles began to experiment aggressively with twisted wire. The interlacing seen in her earlier work breaks out into muscular, sinewy forms with a new, three dimensional interest in spatial perception and a wider range of interrelated fabrication processes. In rings twisted wire became a major part of her technique (Fig. 6); in one example a jewel was not so much part of a setting as it was "chained" in place. Wire intertwined to form hair pins is virtually alive with her creative energy. New materials were also of her exploration and in the early 1920s Payne Bowles was experimenting with "cupror" a new tarnish-resistant and ductile goldlike alloy introduced in 1910 that combined copper and nickel. Three rings survive from the seven Payne Bowles listed in a 1931 inventory as including cupra [sic], but it has not been possible to verify that these rings contain this alloy.

Works by the Danish silversmith Georg Jensen sparked a surge of artistic development in Payne Bowles and a body of her metalwork evinces her awareness of his designs. The open handle of a serving fork (Fig. 7) is one of several examples that recall the "Blossom" pattern flatware Jensen introduced in 1919 and which Payne Bowles may have seen at the Art Institute of Chicago's Jensen exhibition in January 1921. Payne Bowles's Jensenesque flatware marks a significant compositional change in her work, and her pieces begin to interact with space. In the 1920s, Jensen silver was exhibited and promoted in the East and mid-west where Payne Bowles could have seen it: in May 1925, an exhibition of over one hundred pieces of Jensen's silver was on view at the John Herron Art Institute.

By 1921 Bowles was probably making pedestal bowls and cups. Her continuing debt to Jensen is seen in a chalice or salt stand (Fig. 5). Its spirited, whirling columnar stem and sense of movement were undoubtedly inspired by Jensen's designs, particularly his well-known spiral-stem pedestal bowl with pendant grape clusters introduced in 1918. But, if Payne Bowles appropriated Jensen's devices, she rendered them with a vigor and authority that are distinctly her own. This chalice, as well as two spoons whose handles also display the whirling motif, reflect light and imply movement with an intuitiveness seen in contemporary Futurist works also known to Payne Bowles.

A definitive source of influence on Payne Bowles was the composition method of Arthur Wesley Dow. Although she would have been aware of Dow since her marriage in 1895, Dow's integral role in her artistic approach is not readily apparent until the point at which she combined her work with teaching. Indeed, Dow's text Composition, following its first publication by Joseph Bowles in 1899, went on to guide the teaching of several generations of arts teachers: by 1941 it was in its twentieth edition. Dow led the break with academic artistic tradition by approaching art through composition rather than through imitative drawing. He taught that "the many different acts and processes combined in a work of art may be attacked and mastered one by one, and thereby a power gained to handle them unconsciously when they must be used together." Payne Bowles shared Dow's belief in art as an individual activity enhanced by spontaneity. She did not make drawings or preliminary sketches and encouraged her pupils to work in the same way and evolve form as the metal itself suggested.

Payne Bowles was a scholar of all periods of art history and an especially avid observer of vanguard works at exhibitions she regularly attended in New York and other arts center. She practiced Dow's principle of abstraction intuitively, but her accretion approach may have also been encouraged by the collage art of Georges Braque and Pablo Picasso after 1912, and by the Americans Joseph Stella and Arthur Dove during the 1920s. One pendant (Fig. 8), for example, offers a double reading: as a face or as a composition of jeweler's bits and scraps. Her visceral engagement with her materials was a working approach that paralleled the vanguard "direct carving" sculptors Robert Laurent and William Zorach. Payne Bowles may have seen their decorative wood sculpture at the Art Institute of Chicago annual arts and crafts exhibition of 1924-25. These artists were interested in allowing the material itself to influence the form that took shape under their hands. Direct carving can be viewed as in the spirit of the handicraft revival eschewing the fabrication of designs by others or by machines. An illustration to an article in the Indianapolis Star for September 6, 1922, shows her playing the flame from a torch over her work. Soldering, fusing, and molten metal drips are well developed in Payne Bowles's work by 1920. For Payne Bowles her "creative flow" became the flow of molten metals with gravity and other forces of nature her ally.

In late 1924, Payne Bowles received important acclaim as an artist and a metalsmith. Illustrations of Payne Bowles's work and a comprehensive discussion of her artistic principles are found in the long article devoted to her by Indianapolis artist Rena Tucker Kohlman in the International Studio. It included Payne Bowles incisive statements: "The universal and the eternal are my favorite and abiding subjects and I am most conscious of a desire to express them in metal." Her intense interest in the spiritual with regard to religious objects was made clear: "In the objects for religious service, I have tried on the decorative side, to reverse the idea of trans-substantiation, to turn a direct symbol back into the mystery of spiritual underflow and express not history's symbol, but the emotion that produces that symbol." In December, Payne Bowles displayed pendants, spoons, and rings in a group exhibition at the Art Center in New York that also included work by such prominent figures as Georg Jensen. Her work was illustrated in the Bulletin of the Art Center and received a laudatory review in Art News that identified her as "one of the most creative designers working in America today."

Extraordinary progress took place in Payne Bowles's work in the late 1920s. Space become an active component in compositions with the interpenetration of elements and the opposition of solids and voids, and the composition of upright forms. Where a design previously evolved on one place, it now broke out to rise with explosive liberation into exuberant ritual vessels. A modest-sized ladle, with the simple device of a ring foot on the bowl and a winged terminal on the handle, was made to stand; with its sweeping arched handle it took on a formidable presence. In addition to textural contrast, positive and negative space became part of a figural composition in a serving piece. In one instance, a spatula was made to challenge and delight through the visual play of a figure engraved on the mirrorlike surface of its blade reappearing in three-dimensional form on its handle. Rings, too, evidence a new three dimensional interest and a wider range of interrelated fabrication processes.

Just as Payne Bowles's earlier representative images evolved into abstraction, her functional forms, especially chalices, became sculptural. Chalice (Cover) is an astonishing example of the daring plastic experiments Payne Bowles brought to ritual vessels as complex free-standing forms. Unlike her earlier lead box (Fig. 4) where elements were added to surfaces of a preconceived form, here elements are used to generate the form itself. Combining silver alternately raised, cast, or as bent sheet, extruded wire, molten drips, snips and filings, form is made to interact with space, light, and shadow. But, despite the agitated quality of her forms, Payne Bowles always maintains a clear sense of the elements: sheet, rod, and wire retain their unique character and properties. In this and other chalices, traditionally solid elements such as handles and pedestals are punctured with voids or cavities. Elements wrap, encircle, frame, penetrate, and enclose space. Hollows become important with negative space active in the overall arrangement. Allowing no rest for the eye, the play of light and shadow, moving in, out, and over changes of shape and texture, is constantly agitated and evanescent, but nonetheless it resolves formal harmonies of balance and proportion. The arresting and numinous quality of these chalices is a result of this tension between resolved composition and fractured form and surface.

Payne Bowles pushed beyond the Arts & Crafts movement's focus on handicraft as protest against machine production to embrace handicraft as individual artistic expression. Her creative engagement whereby works became explicitly evocative of their materials as well as palpable registers of their maker's physical involvement was an original and pioneering artistic approach. A generation or more passed before this approach was widely considered in the arts.

W. Scott Braznell is an art historian with a specialty in the Arts and Crafts movement of the early 20 th century. He presently lives and writes in Hamden, Connecticut.

The metalwork and jewelry illustrated are on view April 9 to May 22 at the Indianapolis Museum of Art in a travelling exhibition called The Arts & Crafts Metalwork of Janet Payne Bowles.

Notes

For this quotation and the characterization of Payne Bowles as a "forging modernist," see Florenz K. Buschmann, "Janet Payne Bowles Knows Art of Changing Metals into Beauty," Indianapolis Star (April 20, 1930), II, p. 18. For additional references and material this essay draws upon, see W. Scott Braznell, "The Metalwork and Jewelry of Janet Payne Bowles," in Barry Shifman, with contributions by W. Scott Braznell and Sharon S. Darling, The Arts and Crafts Metalwork of Janet Payne Bowles. Indianapolis, Indiana: Indianapolis Museum of Art, 1993. Hereafter cited as Payne Bowles.

For Payne Bowles's work in an Arts and Crafts movement context see W. Scott Braznell's entries in Wendy Kaplan, ed. "The Art That is Life": The Arts and Crafts Movement in America, 1897 - 1920 (Boston: Museum of Fine Arts, 1987).

The winter 1897 edition of Modern Art included Joseph Bowles's review of the exhibition.

Scott Braznell, "Metalsmithing and Jewelrymaking, 1900 - 1920." In Janet Kardon, ed., The Ideal Home 1900 - 1920: The History of Twentieth-century Craft in America. New York; Harry N. Abrams, Inc. in association with the American Craft Museum, 1993, pp. 55 - 63.

Lotys Benning Stewart, "They Achieve, Minds and Hands of Indianapolis Women at Work for Others." The Indianapolis Star, Mar. 29, 1929, part 4, p. 14.

The manuscript had recently been returned by Doubleday-Page & Company who had accepted it for publication. Years later Payne Bowles rediscovered her notes and reconstructed the novel which was published as a "second edition" by Dunstand & Company of New York in 1917.

Rena Tucker Kohlman, "Her Metalcraft Spiritual," International Studio 80 (Oct. 1924), 54 - 57.

"Frederic Allen Whiting Papers," Archives of American Art, Washington, D.C., roll 429, frame 655.

See "Maude Adams to Use Weapon," clipping in the Janet Payne Bowles Archives, Indianapolis Museum of Art.

Janet Payne Bowles, "A Situation in Craft Jewelry," Handicraft 3, no. 9 (Dec. 1910), p. 316; repint in The Jewelers' Circular Weekly 62 (Feb., 1, 1911), pp. 109, 111.

Fosdick, J. W[illiam]. "The Fourth Annual Exhibition of the National Society of Craftsmen," International Studio 42 (Feb. 1911), p. LXXXI.

Payne Bowles, cat. no. 19.

Shortridge Daily Echo, Oct. 4, 1912, p. 3; Feb. 13, 1913, p. 1.

In 1920 Payne Bowles stated, "He (Clarke) introduced me to Mr. Morgan and for four years I did nothing but pieces for his collection."; see Indiana Daily Times, Nov. 29, 1920, p. 9.

Kohlman 1924, p. 57.

Kohlman 1924, p. 55.

Official Catalogue of Exhibitors, Panama-Pacific International Exposition (San Francisco, 1915), p. 74. The document for the award is the Janet Payne Bowles Archives, Indianapolis Museum of Art.

Payne Bowles, cat. no. 64.

See "Neuman's 1931 Inventory" in the Janet Payne Bowles Archives; Payne Bowles, cat. nos. 78, 104, 113.

Payne Bowles, cat. nos. 119, 120.

See Cedric C. Moffatt, Arthur Wesley Dow (1857 - 1922). Washington, D.C.: National Collection of Fine Arts, 1977, p. 132.

Arthur Wesley Dow, Composition (Boston: J. M. Bowles, 1899), p. 3.

Guy Brenton, Indianapolis Women Win in Many Lines of Business and Professions." The Indianapolis Star, Sept. 6, 1922.

Kohlman 1924, p. 54.

See Alice M. Sharkey, "Art Center Notes," Bulletin of the Art Center, New York 3 (Dec. 1924), p. 93; (Jan. 1925), p. 123. See also "Metal Work by Mrs. Bowles," Art News (Jan. 1925), p. 2.

Payne Bowles, cat. no. 85.

Payne Bowles, cat. no. 101.

Payne Bowles, cat. no. 93.

Payne Bowles, cat. nos. 11, 12.

You assume all responsibility and risk for the use of the safety resources available on or through this web page. The International Gem Society LLC does not assume any liability for the materials, information and opinions provided on, or available through, this web page. No advice or information provided by this website shall create any warranty. Reliance on such advice, information or the content of this web page is solely at your own risk, including without limitation any safety guidelines, resources or precautions, or any other information related to safety that may be available on or through this web page. The International Gem Society LLC disclaims any liability for injury, death or damages resulting from the use thereof.

The All-In-One Jewelry Making Solution At Your Fingertips

When you join the Ganoksin community, you get the tools you need to take your work to the next level.

Trusted Jewelry Making Information & Techniques

Sign up to receive the latest articles, techniques, and inspirations with our free newsletter.