David Secrest – The Man with X-Ray Vision

11 Minute Read

On a desk in David Secrest's living room sits an antique ophthalmology machine. Meant for the examination of the inner structure of the eye, it now holds a small irregular chunk of metal, which to the unaided eye appears as a mere nugget of bronze. Upon peering through the eyepiece, however, another world - the microscopic depth of the metal's surface - it is revealed. It is a whimsical, yet prescient introduction to an individual who seems to do nothing on empty whim.

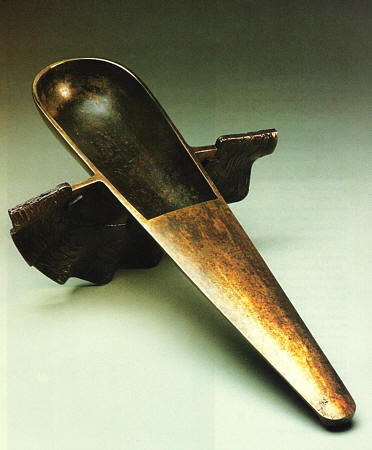

| Winging, 2000 Bonze, Pate de Fer 21 1/4 x 8 x 11″ Photo: Roger Wade |

On a conceptual and even visual basis, the design and structure of Secrest's hand built home/studio is indistinguishable from his metal sculpture. The elegantly rustic building that Secrest has been methodically crafting since 1978 is reflective of how he structures his work. Every surface of timber, wood, window, and stone come together to form a functional engineering of aesthetics and clean joinery. Functionally, it serves as a working space and shelter.

Aesthetically and experientially, it is not unlike peering through his ophthalmometer at one of his sculptures. You ascend the hand wrought stairs from his ground level studio to the second floor living space and upper floor bedrooms noticing the intriguing angles and supporting structures of the building, a magnification of the purposeful composition of elements that are a hallmark of Secrest's work. From every aspect, it is clear that Secrest's way of working is a thorough reflection of not only his intellect, skill, and aesthetic, but his way of living, looking at the world, and his very upbringing.

| Lodestone, 2003 Bronze, Steel 60 x 30 1/2 x 17 1/2″ Photo: Kelly Nelson |

David Secrest is to the manor of craftsmen born. Coming from a family of creative people his father a potter, his mother a painter, his brother Peter now a respected contemporary glass artist - he notes that his training derived from hands on observing and assisting, rather than through formal education. His father and brother Phil built and operated a ceramics studio in New York State, which Secrest considers his primary training ground. His uncle later opened a small gallery and studio in Wellfleet, Massachusetts, where Secrest worked during summers while in high school.

Secrest sees this "lack" of formal training as instrumental to his learning and creative process, just as he views his having lived in rural western Montana for nearly 30 years as integral to the development of his techniques. Being steeped in the world of artisanry as a boy instilled in him an appreciation of craftsmanship, one not tainted or questioned as he suspects it might have been had he gone through a formal study of studio art and art history.

When asked how living in the remote region of western Montana has influenced his work, he does not cite the grand landscape, but rather speculates that had he stayed in the northeast, exposure to, and influence by artists in the mainstream might have altered the necessity of learning his own method by experiment. In by passing the academy, he was unrestricted by someone correcting or redirecting him by saying, this is the way to do it. Without external pressure or supervision, he was free to experiment, and by trial, error, and vision, to develop his own course of creation in rendering sculpture and functional forms of patterned forged iron, fabricated steel, and bronze.

| Rapunzei,1991 Wrought Iron, Steel 31 1/2 x 12 x 6″ Photo: Marshal Noice |

While art historical references exist in Secrest's work, they are non specific, pan cultural. One might recognize elements suggestive of Japanese architecture, African Kuba cloths, Byzantine pattern, or even Neolithic tools, but he feels that his inherent influence is not specific to one culture. He comments, "I think that's what a great deal of art is about, reaching that part of you that is intellectually inaccessible… I don't want people to be able to place it." secrest has an admiration and fascination for the historical and cultural use of ancient tools, and the workers who utilized them in their daily work.

Rapunzel, a wrought iron and steel sculpture from 1991, suggests in its suspended totem, blade like form a non specific archeological finding. Closer inspection reveals a surface shaped by Secrest's signature style: astute aesthetics and a mastery of joining surface textures of varying density and complexity. While some surfaces are relatively smooth and spare, others offer a kaleidoscope of pattern.

The combination of minimal and patterned metal has transformed over time in Secrest's work. The vertically-oriented, exuberant abstract figural works of the 1990s have evolved into a strong, if not exclusive, focus on architectural and functional sculpture. [1] The ophthalmometer assisted view into the surface structure of bronze is more than a mere metaphor for Secrest's fascination with, and study of, the inner structure of materials and finished forms. Secrest is known for being elusive when it comes to discussing the "why" of his process, but his artist statement offers a forensic clue about his design. "Natural objects provide the basis for my sense of design: however, it is the conceptualization of structure and the intentional manipulation of materials that hold my interest."

Among the books in his collection are texts on the physics of soap bubbles, and he freely discusses fractals, with their mathematical observation of the overall structure of, for example, a head of cauliflower bearing a similarity to that of the individual sprig. Secrest is intent upon the structural relationship between the larger whole and individual parts of his works, similar to the way in which structural patterns recur from "galaxies down to nuclei." To contemplate such scale as one sits on one of Secrest's public benches may not be a crucial aspect in its appreciation, but it is, however subliminally, intrinsic to how the form evolved from notion to crafted structure. As he says, "there is present in the finished piece an encrypted history of its making."

| Thicket, 2002 Steel, Cast Bronze 32 1/2 x 19 1/2 x 19 1/2″ Photo: Chris Autio | |

| Froth, 2002 Steel, Cast Bronze 72 x 21 x 16″ Photo: Chris Autio |

This is an artist whose every notion and creation is deliberate, on just such a comprehensive scale; for Secrest, the "doing and making is my world. "The doing and making for Secrest typically begins at the sketchbook. Once IF he sees the image on paper, be senses how it needs to feel, the visual rendering in hand serves to draw out his tactile understanding. Then begins the ciphering, the exploration of materials, and the critical element of orchestrating the metalworking sequence. The sketches themselves are lovely, minimal, and have a subtle sense of movement. They could easily stand alone as fully considered artistic endeavors.

However, for Secrest, they are more practical in nature "Iron is bard to work with, sketches arc not." From there, he will typically prepare stock for the structures, adjust the sketches after beginning to make his materials, refine the form he wants to produce, then "crank it out."

If Secrets were strictly a scientist, he would be a practical, not theoretic, one. When he asserts, "Art without craft would just be a notion," my reticence to discuss that "why" of his work is vanquished. Theory without practice does not hold Secrest's interest. "An idea has value only with the application of craft. I am an artist when I have the idea, when I sketch it I am a designer, when I make it I am metalsmith /craftsman." [2]

The value of his personal experience is in the changes from raw material to object, and bow the object ages. The subsequent response of the viewer is a value unto itself for Secrest. Such recognition of the viewer, especially in his functional public work (furniture), is indicative of Secrest's democratic approach to art, which without a responder has incomplete function, like an unread book. His consideration of the interactive value of architectural furniture recalls that of artist Scott Burton, who conveys a similar concern for the social value of his public works: "… the individual liberty of the artist is a pretty trivial area. Communal and social values arc now more important. What office workers do in their lunch hour is more important than my pushing the limits of my self expression."[3]

| Curbilinear Parallelepipedon, 2000 Steel, Bronze 19 1/2 x 57 1/2 x 21″ Photo: Scott Young | |

| Syncline Saddle, 2000 Bronze, Steel 29 x 41 x 18″ |

The upper surface of Froth (2002), is representative of Secrest's sublime juxtaposition of varying patterns of steel and bronze. This 11 shadow patterning" comes into being by virtue of the viewing angle. A single mosaic pattern of zig- zags becomes interlocking diamonds when the light shifts across the minute differences in surface depth, and my change in the viewer's orientation alters the image. This shape shifting of signature scroll and tile like patterning brings to mind the repeating geometric patterns and spatial illusions of graphic artist M. C. Escher, whose mathematically complex patterns prompt a second look, but are mostly a clever visual pun.

The interlocking patterned surfaces of Froth, or Lodestone (2003), also elicit a second look, but in the case of Secrest's imagery the dovetailing patterns are subtext, not the main content. The intelligence informing Froth is both aesthetic in its graceful curve, and mathematical in its joinery of varying patterns. The angles where patterns are welded together conform to the way that soap bubbles join and organize themselves into specific angles.

This correlation expresses why, for such an artist who shuns straight lines ("they seem weak"), curvature of surface is important. When three patterned surfaces meet along a curve, they do so at angles of 120° with respect to each other. The point at which four boundaries meet will always divide into two, forming two points each, with three adjoining boundaries at 120° (the angle changing to 90° if there is a ridged boundary). This insight into soap bubble mechanics inspires the viewer to look more closely, as if seeing with x ray eyes into the atomic arrangement, the geological strata within.

| Drawing for Curvilinear Parallelepipedon, 2000 |

David Secrest's signature material, which he dubbed pate-de-fer, is a paste of iron files and metal shards that are tightly packed into a container, placed in the forge, and then formed into a concoction that visually suggests the convoluted geological pushing of plate tectonics. While pattern welded steel is an intrinsic element drawing attention to the surface of Secrest's forms, it is not a superficial decoration.

In Syncline Saddle (2000), or Winging (2000), the pate-de-fer lends a sense of a cross-section, a dense, core sample of the sculpture's metal structure. It evokes the observation of crystalline structure and underlying strata, a fascinating look into what's inside. In technique and aesthetics, pate-de-fer grants us an element of x-ray vision. The viewer sees deeper than skin deep, glimpsing how the works might have evolved over geological time from the inside out. Geological occurrence is also evoked in Valley Fault (1999), two tables of bronze and steel. Here Secrest gives a nearly representational rendering of splitting along fault lines, with the upper surfaces clad in variegated shadow patterned metals suggestive of plate tectonics. The viewer senses the relationship of the internal structure to the exterior, of the development from the inner toward outer surface.

Jeffrey Funk, a fellow Montana artist and metalworker, has followed the evolution and singular development of Secrest's work. Funk credits Secrest for using pattern welding iron on an unprecedentedly large, architectural scale. Funk notes that Secrest "designs problems for himself," a statement paralleled by the artist's claim that he "savors the eloquent execution to a difficult problem." Taking on "problems" led to a watershed for Secrest around 1980, as he began patterning iron in ways never done before, working in a tradition used almost exclusively on smaller scale pieces like hand crafted knives and Damascus steel weapons.

| Valley Fault (Two Tables), 1999 Bronze, Steel Photo: Scot Young |

The patterns that result from Secrest's style of patterned welding are evident in the mosaic like surfaces of works such as Lodestone, Thicket (2002), or Curvilinear Parallelepipedon (2000). With their architectural scale, one can appreciate them from a distance, in an open landscape. Lodestone seems slightly ceremonial it could be a throne. Thicket's upper surface is fissured, a "frame" guides the eyes to look down into what lies beneath, and recalls peering through a glass bottomed boat to the wonders below.

These elements are as consistent and varying in Secrest's work as they are in nature. One comes to recognize his forms, their prominent curves, their nearly smooth side panels leading to the patterning at certain junctures and surfaces. As in Curvilinear Parallelepipedon, where scrolls evoke the cool elegance and architectural arrangement of glass blocks, each section of metal merges in a seamless, well proportioned fashion.

| Detail of a metal plate used to produce shadow pattering, 2003 |

One could go into great detail about the "how to" aspects of Secrest's studio work. There would be the metal going into the forge, red hot, then thrown into water, where it gets brittle, and how he breaks it by hand into shards, then lays those down and forges them together. A technical manual could be written with his recipe for folding and slicing ingredients, and at which temperature they sit in the forge. It might have a chapter on the steps of his oxidation process, how he etches and pits the surface, and conjures color variations. Or, one could shift the focus away from the obvious technique to the pondering of the creator and his pursuit of clarity.

An artist who, in explaining the physics of fusing metal equates it to the internal structure of ice and snowflakes, with their unique surface edges. One who speaks about how snow, at first fluffy, becomes stiff when ploughed, and in this telling provides a perfect illumination of his own work for a layman. In such a way, studying Secrest's work heightens our perception and spurs us to seek the bidden workings of all things. If a key role of an artist is to show us things we, may not typically notice, then David Secrest succeeds admirably at this task.

Barbra Brady is an independent writer and curator who lives in Missoula, Montana.

- Taken from wall text written by curator Stephen Glueckert for the exhibition "Primal Visions," 1991, Paris Gibson Square Museum of Art, Great Falls, Montana.

- This and all other unattributed quotes taken from author's conversation and written communication with the artist, June-July 2003

- Douglas C. McGill "Sculpture Goes Public," The New York Times Magazine, 27 April 1986, p. 67.

You assume all responsibility and risk for the use of the safety resources available on or through this web page. The International Gem Society LLC does not assume any liability for the materials, information and opinions provided on, or available through, this web page. No advice or information provided by this website shall create any warranty. Reliance on such advice, information or the content of this web page is solely at your own risk, including without limitation any safety guidelines, resources or precautions, or any other information related to safety that may be available on or through this web page. The International Gem Society LLC disclaims any liability for injury, death or damages resulting from the use thereof.

The All-In-One Jewelry Making Solution At Your Fingertips

When you join the Ganoksin community, you get the tools you need to take your work to the next level.

Trusted Jewelry Making Information & Techniques

Sign up to receive the latest articles, techniques, and inspirations with our free newsletter.