Jeweler Experiences in Tool Design

As you may have guessed, I highly recommend taking out frustrations at the bench on your tools. If you are a jeweler struggling with a process, stop and re-evaluate your tools and procedures. A few swift strokes of a file or a couple of minutes at the grinding wheel can make the tool youve been struggling with much more effective. Take the process of evaluating your jewelry designs a step further by evaluating your tools and processes, as well. Tool design may not become a business for you, but it can help your business be more enjoyable and profitable.

7 Minute Read

Tool design and jewelry design have many similarities. The materials differ, but both are concerned with function and form-and there is a big difference between making custom one-of-a-kind pieces and mass production.

The similarity between tool and jewelry design may help to explain why tools designed by jewelers are vastly different from those designed by tool companies. For example, the AllSet products by Jeff Matthews of Murphy, Texas, and the New Concept Saw by Lee Marshall and Phil Poirier of Bonny Doon Engineering in Bonny Doon, California, and Taos, New Mexico, are tools that embody decades of hands-on bench experience, love of process, and problem solving. Matthews sought solutions to stone setting frustrations and designed tools to make cutting seats for stones easier, while Marshall and Poirier spent years developing a variable speed, variable angle saw that uses jewelers' blades but can cut precisely with no drift. What sets these tools apart from commercially made tools is that they were born of a jeweler's need, and they are often the result of much more time spent in the research and development phase.

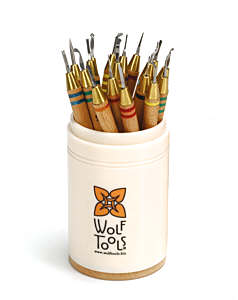

As a jeweler who makes tools, my tool design process is organic and often results from righting a frustration. My Wolf's Precision Wax Carvers evolved from my dissatisfaction with the dental tools and knives that were available. Dental tools are made with soft, gummy stainless steel; when I tried to re-grind them into the shapes I wanted, the edges would roll over, making it impossible to make a sharp bevel or a 90 degree angle. Also, I like to use the long edge of a knife as a wax scraper, but I hate the way X-Acto and scalpel knives flex, resulting in an unacceptable corduroy-like surface.

In response to my frustration with these materials, my manufacturing partners and I sought a superior tool metal and found one in chromium manganese tool steel. (To learn more about how I located tool manufacturers and distributors for my tools, see "Carving a Niche" in the December 2004 AJM.) The material itself solves a lot of problems: For starters, it's a good, hard metal that's not very flexible and is therefore capable of being ground into wicked sharp edges.

Another example of a tool that resulted from frustration with available tools is my Wolf Groovy Chain Nose Pliers, which were developed because I found it clumsy to hold wire and file the ends straight. I made pliers with one side of the jaws coming straight up from the box joint and filed grooves in the jaws (see photos below). Now I can easily hold the wire and file the end perpendicular. After making these modifications, I found other uses for these pliers, such as closing jump rings without having to chase them around the room.

As you may have guessed, I highly recommend taking out frustrations at the bench on your tools. If you are a jeweler struggling with a process, stop and re-evaluate your tools and procedures. A few swift strokes of a file or a couple of minutes at the grinding wheel can make the tool you've been struggling with much more effective. Take the process of evaluating your jewelry designs a step further by evaluating your tools and processes, as well. Tool design may not become a business for you, but it can help your business be more enjoyable and profitable.

Tool Design as Business

Now, for those of you who have considered turning a cool tool idea into a profit center, I can give advice only from my own experience with the process. For starters, if I had approached my tool company as a business person (instead of a head-in-the-clouds artist) and made up a business plan, I wouldn't have entered this business. Even with tool manufacturers putting up the capital for tooling and prototypes, I am supporting their efforts by doing everything I need to do to make sure my products have a chance to thrive in a very competitive market. And tool design is a very expensive business to start and run. Prototype design and development, graphic design, product sales support, printing, packaging, Web site development, trade shows, shipping, and lots of time (e-mailing and on the phone with distributors, vendors, and customers) all cost infinitely more than I imagined. When more of my products are on the market, I'll have a healthy business. In the meantime, I'm running a one-person, coin-operated business-you've got to put another quarter in to get the next job out.

That said, the process is really organic, stemming from both the frustration described earlier and sheer curiosity. I love taking tools from other industries and other eras and seeing if they can be useful to jewelers. I see every tool that crosses my bench as a good beginning.

In her book, "Writing Down the Bones", Natalie Goldberg says, "See revision as envision again." I find this important to keep in mind when designing and evaluating tools. It's crucial to bring in other people (and not just jewelers) for product testing. Have them use and abuse the tool to see what it takes to make the tool fail. Sometimes revision means simplifying a product to hit a better price point. For example, I have been working on developing a bench organizer for more than two years. In the transition from prototype to production, it got a bit too complicated in design, causing the retail price to be higher than we anticipated. However, my manufacturing partner George Khanduja of Mahwah, New Jersey-based Ikohe, and I are determined to get the organizer to the point where it fulfills all the storage needs we desire and sells at a reasonable price.

In addition to using all the practical knowledge you have from years of experience at the bench, you'll have to learn a lot more to make an excellent tool. I'm fascinated with all I need to learn to do this new job of mine. For example, I'm learning a lot about steel alloys. There are an infinite number of them, all with vastly different properties-and choosing materials that will allow your tool to be both functional and affordable is key.

I'm also learning about production processes, plastic injection molding, and how expansion/contraction and humidity affect tools that are made up of various materials. The more you know, the more informed you are to make the best decisions and communicate better with distributors.

While digesting all this new knowledge, you need to concentrate on the first step of taking a tool idea to a tool reality: mocking up prototypes. It's important to make a minimum of three prototypes, so that all participants in the process-you, the liaison between you and the factory, and the factory-have a prototype.

To start the process, I'll mock up a 3-D prototype or take a photo of an existing tool and manipulate it in Photoshop, then send all related items to my manufacturer with detailed measurements and specifications. I recently invested in a lathe and milling machine to help mock up prototypes. Eventually, I plan to learn CAD/CAM for prototype development. Yet however it's done, the process takes time and money: It's not unusual for a tool to take two years to go from idea/design/prototype to production. And don't expect manufacturers to pay for your prototype development. They spend a bundle doing prototypes on their end, so you can expect to fund your own R&D.

I am fortunate to work with established tool manufacturers. Most of my tools are made by Ikohe, and some are made by EURO TOOL in Grandview, Missouri. These companies have existing domestic and foreign factories that they've worked with for decades. The factories count on a high volume of repeat business from them-so they probably won't knock off the work and sell it out the back door. (This is a huge concern when having product made overseas, where patents are scoffed at.) These companies know which production processes to use for each tool, which factories are best suited to manufacture them, and what volume they can expect from the factories. Since they are distributors as well as manufacturers, they can predict demand for the product and project the size of the production run, which often determines production processes. They also know import/export considerations and place high volume orders that get them better pricing.

Now that I'm a few years into this, I'm glad I took the risk. I love it. I love tools and being around people who are passionate about them. The best reward is knowing that my tools have made a difference-hearing that my tools have helped someone do their job faster and more enjoyably.

The award-winning Journal is published monthly by MJSA, the trade association for professional jewelry makers, designers, and related suppliers. It offers design ideas, fabrication and production techniques, bench tips, business and marketing insights, and trend and technology updates—the information crucial for business success. “More than other publications, MJSA Journal is oriented toward people like me: those trying to earn a living by designing and making jewelry,” says Jim Binnion of James Binnion Metal Arts.

Click here to read our latest articles

Click here to get a FREE four-month trial subscription.

You assume all responsibility and risk for the use of the safety resources available on or through this web page. The International Gem Society LLC does not assume any liability for the materials, information and opinions provided on, or available through, this web page. No advice or information provided by this website shall create any warranty. Reliance on such advice, information or the content of this web page is solely at your own risk, including without limitation any safety guidelines, resources or precautions, or any other information related to safety that may be available on or through this web page. The International Gem Society LLC disclaims any liability for injury, death or damages resulting from the use thereof.

The All-In-One Jewelry Making Solution At Your Fingertips

When you join the Ganoksin community, you get the tools you need to take your work to the next level.

Trusted Jewelry Making Information & Techniques

Sign up to receive the latest articles, techniques, and inspirations with our free newsletter.